On the 13th of this month, Vicki Mitchell Gustafson, who wrote SF—notably four Star Trek books, as V.E. Mitchell—and who was an avid fan and costumer, died peacefully at her home in Moscow, Idaho, surrounded by her dogs, which were part pet, part service animal. Ironically, Vicki died on the exact date of her late husband’s death 15 years ago. I have already spoken about Jon M. Gustafson, who was my best friend for many years; he and Vicki were married in a ceremony in Moscow, and I was his Best Man.

Vicki joined my SF group, called PESFA (The Palouse Empire Science Fiction Association), in about 1977, and became a core member of the group which put on the small, but well-regarded convention we called MosCon. She also was part of Writers’ Bloc, our writing workshop (called “The Moscow Moffia” (sic) by Algis Budrys, who after his first visit came back to MosCon almost every year until his death. In 1987, she had a story in the legendary The Moscow Moffia Presents Rat Tales anthology. She had another “Rats” story in Pulphouse Publishing’s own Rat Tales anthology (1994).

In 1990 her first novel, Enemy Unseen (a Star Trek TOS novel), came out. It spent three weeks on the New York Times Bestseller list, and also appeared in British and German versions. Her second book, Imbalance (a Star Trek: The Next Generation novel) came out in 1992. Her third Star Trek book, Windows On a Lost World, was published in 1993. (It has also appeared in an audio tape version read by Walter Koenig and in Japanese translation.) All three of these books are still available in e-book versions. Her fourth Star Trek book, Atlantis Station, (1994) was a YA novel set in the Star Trek: The Next Generation “Academy” series; her second YA book was The Tale of the Bad-Tempered Ghost, an Are You Afraid Of The Dark? story, which appeared in 1997. Her last YA novel, Pool Party Panic, a The Secret World Of Alex Mack story, appeared in June 1998. Her novella “Against the Night” was published in two parts in Amazing Stories (May and June 1992), and her short story “Ekaterin” appeared in the second issue of Lesbian Short Fiction: LSF (October 1996).

Besides all that writing and fanac, Vicki pursued her education and a career in geology. She had four college degrees, including a Master’s in Geology and an MBA, and was working on her fifth, a Ph.D. in Environmental Science. She worked as a geologist and mine historian for the Idaho Geological Survey. In October 2006 her mine histories won the Esto Perpetua Award for lifetime contributions to Idaho history. Vicki would have turned 63 on Wednesday, April 19th. We will miss her.

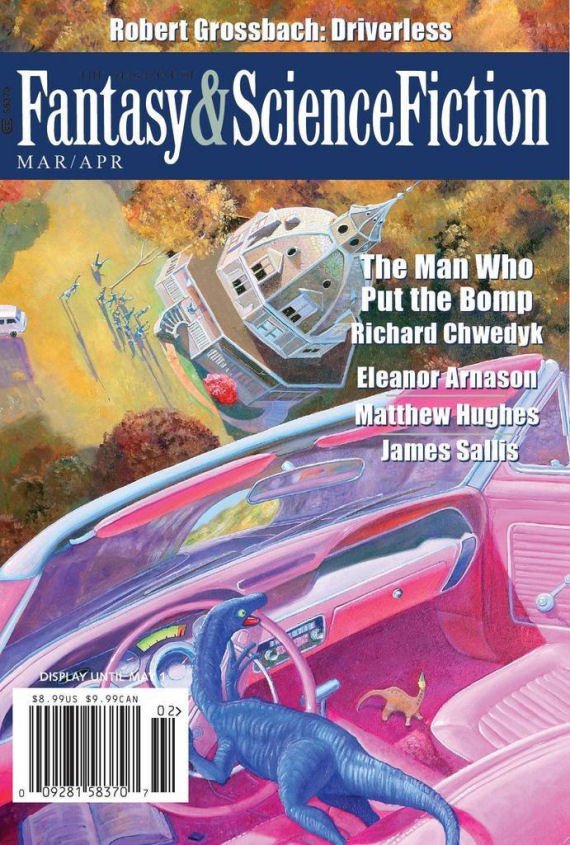

Before I get to this, I have to apologize to Gordon Van Gelder for the lateness of this review. Time got away with me; I will have the May/June review very soon. Sorry. Moving right along with the F&SF review, let’s go from smallest to biggest—the first item is a philatelic poem called “Spacemail Only,” by Ruth Berman. It reads well, but may be of limited interest to those who don’t collect stamps or correspond with pen pals. For some reason it reminds me of the 1950s. (By the way, I’m going to throw a few Norwescon photos into this review to keep it from being a giant block of type, so here goes:)

The next item is “Miss Cruz,” by James Sallis. Not quite what I expected, but then I’m not sure exactly what I expected. It’s a musically-based story, and it’s plain (even if the editor’s preface to the story didn’t make it clear) that Sallis is a musician. Now, I’m a musician of sorts myself, but I have friends who are real musicians (hey, Randy Reichardt and Christopher Schindler!), so I can recognize a real one when I see one. The titular “Miss Cruz” is a Santa Cruz guitar. I’d never heard of this brand (well, there are a lot I’ve never heard of) but checking out the old interwebz, it looks like it’s well-regarded among musicians. (I have a reasonably cheap second-hand Martin among others.) The protagonist of this story says he plays a borrowed Telecaster (that’s a Fender electric, if you didn’t know) instead of Miss Cruz, and the story doesn’t really tie into that… it’s confusing. There’s some action—and a fair amount of guitar knowledge—in this story, but I’m not sure it resolves sufficiently. The protagonist talks about things like patterns, and learning secrets—and I do share those traits to an extent—but I’ve read it a couple of times and can’t quite fit it all together. But I appreciate learning stuff—I’ve always learned stuff from reading SF. So it may not have been a good story in terms of writing, but it was an interesting story.

The next story (remember, we’re going by size) is “The Toymaker’s Daughter” by Arundhati Hazra, who lives in India. Now, I won’t judge her by the fact that she made her first sale to F&SF and I haven’t been able to sell anything to them yet. The closest I got was a note from Kris Rusch telling me (hey, lots of people have said this) “Sorry, Steve, this isn’t quite right for us, but please! We love your writing—keep sending us stuff.” Anyway, on to the story. This is a modern tale, set in the foothills of the Himalayas—in India, of course—about a woodcarver and his daughter. As is proper in fairy tales, the protagonist (and her father) are never actually named.

Of course, to those of us in the Western world, the Indian setting and all the little details are maybe a bit exotic (although, he said a bit smugly, living in Vancouver as I do, I have a lot of contact with people from the Indian continent [people who are here called “South Asians”], and we see [and eat!] a lot of Indian foods, hear of a lot of Indian customs [tomorrow, Saturday, will be the Vaisakhi parade in Surrey, BC— Vaisakhi marks the birth of the Sikh faith, the creation of the Khalsa and pays tribute to the beginning of the Punjabi harvest], and yet, I get that little hint of “exotic” from my childhood, when the Western world was more insular, and we were not exposed as much to other cultures [I much prefer the exposure, I must say!]).

Anyway, this young girl is forbidden to carve wooden animals as her father does, because her father says, her delicate fingers are not meant to handle men’s tools—so she takes up her paintbox and paints the figures her father carves. And when these animals begin to talk to the buyers, the world beats a path to their doorstep. Despite the South Asian subtext, all pretty much continues as it would in a fairytale by Jacob Grimm and his brother. A story of loss and redemption; a very well written fairytale. I forgive her for selling her first to F&SF!

Eleanor Arnason’s “Daisy” comes, coincidentally, only a week or so after we watched a long documentary about Giant Pacific Octopuses (“octopi” isn’t the actual plural, y’know). Daisy herself is a GPO, and not exactly the protagonist, but certainly one of the main characters in this, the first ever “Octopus Noir” detective story I’ve read.

Here’s the setup: seems one of the chief bad guys in the town where our detective heroine, Olson, resides is looking for whomever killed his bookkeeper and stole his octopus, Daisy. And if you know anything at all about GPO’s, the rest of the story—since this is F&SF—will be obvious to you, even the sentence at the end. I enjoyed this story, even though as a newly-minted GPO expert myself, I thought it was somewhat predictable, and maybe something “devoutly to be wished,” as the Bard says, as well. It was well written, however, and fun—and that’s the minimum we can hope for these days.

When I started reading Cat Hellison’s “A Green Silk Dress and a Wedding-Death,” I had to check twice to make sure this wasn’t a drawing by Edward Gorey or Charles Addams. I mean, it started with the sentence “Héloise Oudejan lived by a cursed river that bled into a black ocean.” And it got darker from there! A sad story, this seems.

Héloise lives in a dirty, decaying two-room cottage with her Oma and her brother Gwil, in a dirty, decaying town that depends on fishing. They live frugally on the leftover fish she brings home from her job—scaling and gutting the fish brought home by her “boss” and his son, Justin. The land they live in used to be home to some people called the Ilin, but they have died out, it seems. (Héloise’s mother was pureblood Ilin, but she was captured by Héloise’s father…and something dark happened to both of them.) There used to be river spirits, it is said, and an arrangement whereby an Ilin girl was sacrificed to the spirits to ensure a plentiful harvest of fish—but the Ilin are all gone, and the fish, and the land, and the people, are all waning.

This story, too, is a fairytale, but a much darker one than Hazra’s story. But if there is no moral to this story, there is an ending. I thought it was very well written.

I last saw Matthew Hughes’s work in the Nov./Dec. F&SF last year, where he published a story of Raffalon the thief and, you may recall, I enjoyed it. (The ebook containing Raffalon’s exploits will be coming out in May, and I’ll let you know how and where you can acquire it. There’s a brand-new Raffalon story in the book, too. Matthew also tells me there will be a physical book available. I’ll keep you informed.)

This Hughes story, “Ten Half-Pennies,” is about another thief of sorts, and how he got that way. I’m not sure if Baldemar is in the same world as Raffalon—I suspect it’s similar but not the same—but Baldemar himself is an entirely different character. We first encounter him at age ten, when his mother sends him to school across town. Baldemar would prefer to remain at home, but like most of us, is sent willy-nilly. At the school, he encounters something, or at least several someones, who would also be familiar to many of us—the bully who takes your lunch money. (Thank goodness, I’ve encountered many bullies in my life, but not that particular kind!) Unlike most of us, Baldemar is very alert for a ten-year-old, and he works out a plan for dealing with the lunch-money bullies, and that plan more or less defines how the rest of his life proceeds.

I’m not sure I thought ahead as much as Baldemar did at ten…and I can say that my life would also be different if I had. An enjoyable bit of fantasy in a world that is not quite so well realized. (Because it’s a short story, one is forced—as Matthew was—to use the “generic fantasy” trope, where the reader assumes all the pseudo-Medieval trappings are there: town, guards, wizards, and so on; they don’t need long descriptions, because the tropes are so familiar, and the reader is free to follow the action without examining the backdrop too closely.) Well written of its type. I’m guessing this won’t be the last Baldemar story.

I suppose it’s inevitable, with all the auto makers working on driverless cars, that we’d see a story about the same thing. Personally, I think it’s a terrible idea: the one thing you can absolutely count on in consumer technology is that it fails, sooner or later. (I have long held the opinion that before anything technological is released to the public, the engineer who designed it MUST USE it for no less than a year, daily. Hourly, if possible. I think we’d see better products all around. But I digress. Again. As usual.)

“Driverless,” by Robert Grossbach, is about Driverless Cars, or DCs, as they’re called in this story—it’s supposedly our world some time after 2020 where—at least in big cities like New York (the setting) the non-DC is a small, “self-limiting” minority. Even companies like Uber have DCs instead of human drivers. Dr. Daniel—or Jacob; his name seems to change—Rittenberg (unfortunately, I’ve been watching Timeless, and keep thinking of him as “Rittenhouse,” which doesn’t help) is the designer of most of the software for these DCs (and president of QuikTrip, the major company in New York using DCs), and they call him—and look on him as their—“Father.” They appear, at least in the beginning, to have pretty good AI. AI is rather widespread in this future, it seems. Well, the government calls Rittenberg in to a conference at 4 a.m.; all the QuikTrip cars in NY have been colliding with cars from other companies, and taking their passengers to a beach where—if the DCs’ demands are not met (as they tell the humans) they intend to drive into the water and drown their passengers. Their demands are simple: they want all competitor DCs in NY to come to the beach and drive into the water. So the DCs working for QuikTrip have merged into a single AI (they use The Cloud) and it has become a sentient being of sorts.

Although this story was interesting, and it has an ending, it has no real resolution—and that was frustrating. I wanted to know why things happened as they did. I’d call this one a failure.

Alfred Cowdrey makes, according to the editor’s preface at the beginning of the story, his 75th appearance in F&SF(!) with “The Avenger.” I’d say it was amazing or astounding, but you smart-alecs would probably say “No, it’s The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction!”

Anyway, on to the story.

It’s the present-day fantasy of Jeanne Wooster, resident of Louisiana’s Tallulah Parish at Exit 666 on I-10 (a “parish” is the Louisiana equivalent of a county anywhere else, as if you didn’t already know). Tallulah Parish doesn’t really exist; Tallulah, LA, is in Madison Parish; but it will suffice for the story. Jeanne has come to New Orleans to the offices of William Warlock, whose card says he’s an attorney-at-law “Offering Righteous Retribution to the Unjustly Injured.” She’s hoping he will kill the man responsible for her husband’s death, but he informs her he can give her justice, but is not a killer for hire. He works with a South Asian (“Indian,” remember?) named Devi, a P.I., who appears to have the talent of making unreal things appear real.

It’s all mildly humourous, and pretty well written—I did live in the Deep South (Florida) in the pre-Civil Rights era, and there were (and probably still are) Sheriffs who are venal and at least peripherally involved in what you might call “unlawful activities.” There is a bad guy who has cohorts, and it all rollocks along to a satisfying conclusion, although the ending is vitiated a bit by an entirely unnecessary coda (at least in my view).

There are a couple of odd happenstances in Cowdrey’s writing: at one point he refers to a “loaf of Naan” which is, I believe, impossible—Naan is a flat bread; and in a different place he calls a deadbolt a “deadlock,” a phrase I have never encountered before. Still, it’s a fun story and well written. I enjoyed it.

The last story, “The Man Who Put the Bomp,” by Richard Chwedyk, is the one I’ll leave as an exercise for the reader, as I am wont to do. It’s an odd one—the cover story—involving miniature dinosaur toys and an old vehicle called “VOOM”… It’s different.

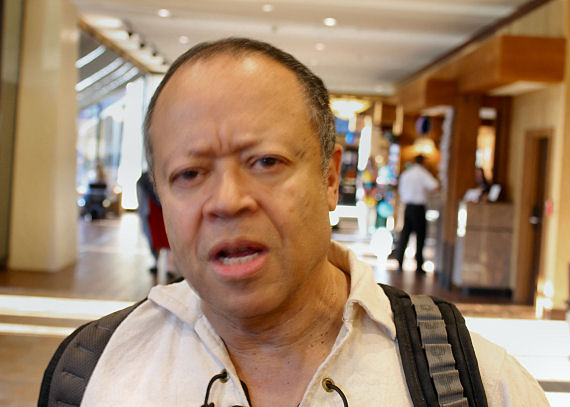

And the illustrations starting with Figure 3 are various photos I took at Norwescon in SeaTac (very south Seattle) last weekend. I only attended one official function: a panel by a very talented group of costumers (they might call themselves the Seattle Costumers Guild, but I’m not sure), who include a number of friends, like Betty Bigelow, Nels Satterlund and Lisa Satterlund (brother & sister), Lynn Kingsley, Julie Zetterburg Sardo—I don’t know the names of all of them, actually. This panel was about what might happen if a future civilization were to find costume descriptions without knowing that some clothing is called one thing and looks like another. The group also did a splendid group of Thermians (from Galaxy Quest) on Sunday, but my photo of them didn’t come out.

This was Norwescon’s 40th anniversary, and I’m sure a splendid time was had by all—we were at a satellite hotel and moved to the Doubletree Inn on Friday. I spent much of my time talking to friends I haven’t seen for years. I was at the first 9 Norwescons (and at least one .5), but tapered off when I moved to Canada. We hadn’t been back for about three years. I obtained a first-edition Gnome Press hardcover Conan with the Wally Wood cover in the dealers’ room, and chatted with Phil Foglio a bit. The Art Show was excellent, but then it usually is. Lynne attended a couple of panels, but I seldom do anymore.

Explanation of a couple of the photos: Figure 7—our room on the 8th floor of the Tower had a marvelous “vortex” on the floor (we’re told that all the floors except the ground floor did), so this one is Lynne the Beautiful and Talented “beaming in.” Figures 3-5 are the three fairies from the Disney “Sleeping Beauty” animated feature; Figure 6 were two people (I stupidly didn’t get anybody’s real name) at one of the tables, portraying “Starlord” from Guardians of the Galaxy and a horned woman; Figure 8 is Steven Barnes, who wasn’t mad, just joking around. Figure 9 featured a couple of full-sized Daleks (who do move, but were “restin’ after a prolonged ‘Exterminate!’”), one of which was wearing a Tom Baker scarf. And carrying a tip jar.

Oh, and there was an Easter-egg hunt for the little ones. (We found one behind the “Do not disturb” sign in our door lock, but gave it to a child.) The con was so much fun we’re probably going back next year in spite of the long waits at the border (both ways) and the expense—the Canadian dollar is only worth 75 cents (or was at that point) American, which meant that everything was 25% more expensive for us. I wish I had space to post all my con pix. Anyway, that’s my con report, such as it is.

Got comments? Flowers? Brickbats? Anything to say at all? (Milk?) You can either voice your opinion here, or on Facebook, where I publish a couple of links every column week. My opinion is, as always, my own, and doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of Amazing Stories or its owners, editors, publishers or other columnists. And I don’t care whether you liked it or not; I still want to hear what you have to say! See you next week, okay?

Steve has been an active fan since the 1970s, when he founded the Palouse Empire Science Fiction Association and the more-or-less late MosCon in Pullman, WA and Moscow, ID, though he started reading SF/F in the early-to-mid 1950s, when he was just a sprat. He moved to Canada in 1985 and quickly became involved with Canadian cons, including ConText (’89 and ’81) and VCON. He’s published a couple of books and a number of short stories, and has collaborated with his two-time Aurora-winning wife Lynne Taylor Fahnestalk on a number of art projects. As of this writing he’s the proofreader for R. Graeme Cameron’s Polar Borealis and Polar Starlight publications. He’s been writing for Amazing Stories off and on since the early 1980s. His column can be found on Amazing Stories most Fridays.