The skies are ablaze with fire. People are fleeing in panic. Buildings lay in ruins. Towering over this apocalyptic scene are a trio of mechanical structures, each standing atop three thin legs. One is blasting a ray at the crowd below; one is holding a screaming captive in a tentacle-like appendage; and the third is doing both at the same time. It was August 1927, and the Martians had landed.

The skies are ablaze with fire. People are fleeing in panic. Buildings lay in ruins. Towering over this apocalyptic scene are a trio of mechanical structures, each standing atop three thin legs. One is blasting a ray at the crowd below; one is holding a screaming captive in a tentacle-like appendage; and the third is doing both at the same time. It was August 1927, and the Martians had landed.

This month’s editorial deals not with wondrous new inventions or futuristic possibilities, but with the dismal science of economics. Hugo Gernsback announces that the magazine has finished its “experimental period” and is now “on a fair road to success”. However, he states that it is still not pulling in a profit, and will not do so until it has around twenty or thirty pages of advertising per issue. In the hopes of expanding his readership, Gernsback implores readers to send him the names and addresses of friends who might be interested in Amazing, so that unsold copies can be posted to them. “After all, we are doing pioneer work with an entirely new and different kind of magazine, and must, therefore, have whatever assistance you can give us by sending us good prospects and then let the magazine succeed on its own merits.”

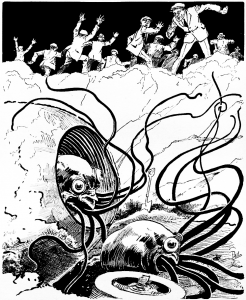

The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells (part 1 of 2)

Continuing its republication of H. G. Wells’ best-loved stories, Amazing begins serialising his 1898 novel of alien invasion: The War of the Worlds. Neatly demolishing any assumption that extra-terrestrials would necessarily be human-like, Wells has mollusc-like Martians attack Earth. They arrive in metal cylinders – presumably fired from guns in the fashion of Jules Verne – before taking to gigantic mechanical tripods as they march upon London.

Continuing its republication of H. G. Wells’ best-loved stories, Amazing begins serialising his 1898 novel of alien invasion: The War of the Worlds. Neatly demolishing any assumption that extra-terrestrials would necessarily be human-like, Wells has mollusc-like Martians attack Earth. They arrive in metal cylinders – presumably fired from guns in the fashion of Jules Verne – before taking to gigantic mechanical tripods as they march upon London.

Vivid portrayals of everyday English folk are set alongside scenes of dreamlike strangeness as three-legged giants stride across the nocturnal countryside. The unnamed protagonist, an everyman caught up in the destruction, narrates from the perspective of having already seen the invasion in its entirety, thereby adding a distinctly fatalistic tinge to the story. The War of the Worlds remains a stark portrait of the apocalypse, one with a heavy element of cultural criticism: as the first chapter points out, the Martians ultimately view humanity the same way that terrestrial empires have viewed colonised peoples.

“The Retreat to Mars” by Cecil B. White

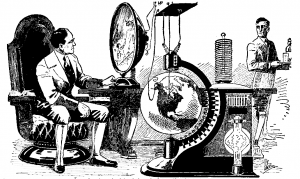

Arnold, an astronomer interested in Mars, is visited in his observatory by an archaeologist named Hargraves, who brings a remarkable tale. Having become persuaded that “the rise of mankind took place, not in Asia where it is generally supposed to have occurred, but in Africa”, Hargraves took a trip into central Africa where he found a large metal structure buried in an edenic valley.

Arnold, an astronomer interested in Mars, is visited in his observatory by an archaeologist named Hargraves, who brings a remarkable tale. Having become persuaded that “the rise of mankind took place, not in Asia where it is generally supposed to have occurred, but in Africa”, Hargraves took a trip into central Africa where he found a large metal structure buried in an edenic valley.

His crew excavated part of the structure, including an entrance. After bypassing an elaborate series of keys Hargraves descended through the metal tunnels until he found a book-like metal object containing “a picture in three dimensions… I ran my fingers lightly over the surface to assure myself that it was not a model, or in relief, but it was as flat as a table top”; this illustration depicted an unknown species of animal, and by adjusting levers, Hargraves was able to make the image change. Various other such “books” were nearby, containing both three-dimensional images and words in an unknown alphabet; some were simple enough for Hargraves to learn the language. From these volumes, he was able to learn the full history of the Martians who built the subterranean structure.

The Martians, the story reveals, long ago made themselves “mentally and physically perfect” through eugenics. However, they were still faced with a natural depletion of water on their planet; they responded first by constructing the fabled canals of Percival Lowell before later turning their eyes towards Earth.

Their first expedition to Earth ended in disaster, as their bodies were unable to function under the heavier gravity of the planet. Back on Mars, they spend the next four centuries eugenically breeding a race capable of functioning on Earth; the resultant individuals were nine feet tall, with enormous chests but weak limbs.

The Martians then set up a colony on Earth, and began reproducing. Their terrestrial offspring turned out to be smaller in size, sturdier in limb, and – catastrophically – less intelligent than the original colonists. With the fourth generation, the colonists had become “but a grotesque caricature of the original stock… already forming into bands of nomadic savages”. These were, of course, the first humans.

The surviving members of the original colony saw that their plans had failed, and so decided to depart. Before doing so, they left stockpiles of their knowledge in the hopes that their earthbound descendants would someday be intelligent enough to appreciate it – and it was one of these stockpiles that Hargraves had discovered.

After concluding his story Hargraves shows one of the metal books to the astronomer, who is fascinated by the three-dimensional images of Mars and its society.

With a rather thin plot and a heavy reliance on its era’s faith in eugenics, “The Retreat to Mars” is interesting mainly as an early example of the ancient astronaut concept – an idea that was later touted in all seriousness by the likes of Erich von Däniken. As an aside, it also offers a precursor to the holograms that are now such a common SF accessories. Cecil B. White’s sequel, “The Return of the Martians”, ran in the April 1928 Amazing.

“The Tissue-Culture King” by Julian Huxley

During an expedition through an African swampland, the narrator encounters a pair of unusual sights: first, a two-headed frog; and then, “the biggest man I had ever seen outside a circus”, a nine-foot-tall African. After the narrator is taken captive by the towering natives and marched through a series of villages, it turns out that each of these sights is actually par for the course in this locale: “Every now and then some new monstrosity in the shape of a dwarf or an incredibly fat woman or a two-headed animal would be visible, until I thought I had stumbled on the original source of supply of circus freaks.” Arriving at the capitol (“a regular Barnum and Bailey show”) the protagonist meets an Englishman named Hascombe, who explains all.

During an expedition through an African swampland, the narrator encounters a pair of unusual sights: first, a two-headed frog; and then, “the biggest man I had ever seen outside a circus”, a nine-foot-tall African. After the narrator is taken captive by the towering natives and marched through a series of villages, it turns out that each of these sights is actually par for the course in this locale: “Every now and then some new monstrosity in the shape of a dwarf or an incredibly fat woman or a two-headed animal would be visible, until I thought I had stumbled on the original source of supply of circus freaks.” Arriving at the capitol (“a regular Barnum and Bailey show”) the protagonist meets an Englishman named Hascombe, who explains all.

Hascombe, a biologist, had been taken captive fifteen years previously. Finding that the natives had a religious rite involving blood, he was able to impress them by showing them a droplet of blood under a microscope, and explaining that the visible cells were “people” over whom he had powers. Intrigued by his work, tribe then allowed him to set up a series of rudimentary laboratories – which he collectively nicknamed the Institute of Religious Tissue Culture. He found an ally in Bugala, a prominent religious leader of the tribe, who saw an opportunity to use Hascombe’s knowledge for his own ends.

Partly with the aid of Bugala, and partly with his knowledge of primitive religion gleaned from James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough, Hascombe was able to integrate his experiments into the belief system of the tribe. Donations of tissue became a sort of holy sacrifice, to the extent where female donors formed a caste of priestesses dubbed the Sisters of the Sacred Tissue. Meanwhile, Hascombe successfully encouraged the tribe to retain living tissue of their dead as an act of ancestor worship.

Inspired by “the craze for ‘glands’ that was going on at home years ago, and its results, in the shape of pluriglandular preparations, a new genre of patent medicines, and a popular literature that threatened to outdo the Freudians”, Hascombe branched out into glandular injections so that certain infants of the tribe would grow into giant guardsmen or holy freaks:

I took advantage of the fact that their religion holds in reverence monstrous and imbecile forms of human beings. That is, of course, a common phenomenon in many countries, where half-wits are supposed to be inspired, and dwarfs the object of superstitious awe. So I went to work to create various new types. By employing a particular extract of adrenal cortex, I produced children who would have been a match for the Infant Hercules, and, indeed, looked rather like a cross between him and a brewer’s drayman. By injecting the same extract into adolescent girls I was able to provide them with the most copious mustaches, after which they found ready employment as prophetesses.

Not content with his biological research, Hascombe has since branched out into psychical research, and gives the narrator a demonstration of the “superconsciousness” that he can manifest amongst the tribesmen by hypnotising them and forcing them to act as one through telepathy.

Seeking a means to escape, the narrator persuades Hascombe that he should take his findings back to England. They succeed in hypnotising the tribe, but as they make their escape, Bugala turns the telepathy against them and tries to will them to return. The narrator breaks free and reaches England, but Hascombe returns to the tribe and suffers an unknown fate.

This 1927 foray into fiction by a noted evolutionary biologist offers a portrait of colonist as mad scientist. To a modern reader it is chilling, although as Huxley was an ardent eugenicist, it is debateable as to whether he intended this response. Notably, the narrator seems to be mainly concerned that Hascombe’s research will fall into the wrong hands – as though it has not already been put to unethical use.

“The Ultra-Elixir of Youth” by A. Hyatt Verrill

This story begins with the announcement that the elixir of life, long sought by humanity, was finally discovered within the past three years by one Doctor Elias Henderson. This individual, along with nine members of his social circle, have all vanished under mysterious circumstances, leading to all manner of speculation; and so, the remainder of the narrative details the full story…

This story begins with the announcement that the elixir of life, long sought by humanity, was finally discovered within the past three years by one Doctor Elias Henderson. This individual, along with nine members of his social circle, have all vanished under mysterious circumstances, leading to all manner of speculation; and so, the remainder of the narrative details the full story…

The narrator is Henderson’s replacement as the local university’s Professor of Biology. Inheriting Henderson’s old laboratory, the protagonist is startled to find discarded baby clothes in the rubbish – babies had been seen around the university shortly before Henderson’s disappearance, leading to lurid speculation that the professor was involved in child sacrifice. Digging further, the narrator finds more clothes and toys intended for babies, along with Henderson’s old journal.

The journal outlines Henderson’s attempts to device a means of halting cellular decay, thereby affording endless youth. The vanished professor had noticed a report that an airship explosion had a strange effect on the village below the disaster, with people and plants alike apparently rejuvenated; he attributed this to the “QW gas” filling the airship, and got hold of this substance for his experiments. The secret turned out to be a previously unknown element, duly labelled Juvenum, contained within the gas.

The journal goes on to outline some of the philosophical issues raised by Henderson and his fellow scientists following their discovery; these include the ethics of keeping or sharing the secret, the psychological effects of staying young while loved ones grow old and die, and the religious implications of avoiding the afterlife. None of these concerns were enough to prevent the researchers from testing the Juvenum on themselves, however.

And therein lies the cause of their disappearance. Instead of halting the ageing process, the Juvenum actually reversed it: Henderson’s fellow researches transformed back into adolescents, then into babies, then into embryos, and finally into nothingness. The final pages of the journal recall Henderson’s horror at the spectacle (“I shiver with terror at the sight, for the agony of mind which is theirs is stamped upon their baby faces”) and his final decision to take the Juvenum himself and so join his wife, who was amongst the vanished subjects.

The premise of “The Ultra-Elixir of Youth” has been seen many times since, but this execution of the idea remains effective due to Verrill’s flair for the macabre.

“Electro-Episoded in A.D. 2025” by E. D. Skinner

Lieutenant-Colonel Algernon Sidney St. Johnstone wakes up after imbibing some rather strong bootleg alcohol, and receives a call from his fiancée Esmerelda. The two had previously got into a row when Algernon criticised Esmerelda’s choice of attire (likening her dresses to picture-frames, on the grounds that “they merely furnished the setting for emphasizing the details of the things revealed”) causing her to huffily fly off in her private biplane. She tells him that her plane has crashed, leaving her with a broken leg, and is now troubled by a tiger – and so, after assuring himself that the tiger must be no more than a misidentified goat, he sets off to rescue her.

Lieutenant-Colonel Algernon Sidney St. Johnstone wakes up after imbibing some rather strong bootleg alcohol, and receives a call from his fiancée Esmerelda. The two had previously got into a row when Algernon criticised Esmerelda’s choice of attire (likening her dresses to picture-frames, on the grounds that “they merely furnished the setting for emphasizing the details of the things revealed”) causing her to huffily fly off in her private biplane. She tells him that her plane has crashed, leaving her with a broken leg, and is now troubled by a tiger – and so, after assuring himself that the tiger must be no more than a misidentified goat, he sets off to rescue her.

“Electro-Episoded in A.D. 2025” is a story which, like Gernsback’s own Ralph 124C41+, offers a checklist of futuristic inventions. These include radio devices small enough worn as jewellery; an Electric Regenerator, which allows a person to regulate the length and depth of their sleep so that they can experience a good night’s rest in mere seconds; pasteurised water on tap; tablets nutritionally equivalent to entire meals; and an atomic-powered, bottle-shaped vehicle that sprouts wings at the push of a lever.

But crucially, unlike Gernsback’s rather dry novel, has a heavy sense of humour. A product of the prohibition era, it portrays a future where not only alcohol is banned, but also tobacco and coffee – although Algernon is able to procure these illicit substances and stores them in vending machines. Meanwhile, a “Purity League” uses helicopters to pursue women caught wearing skimpy dress.

The story’s editorial introduction flags up its comedic nature as a novelty in comparison to much of the wider science fiction genre:

Humor, we have been told by some of our critics, can never amount to much in scientifiction. If we may let a secret out of the bag, the Editor has been on a rampage, lately, to find a scientifiction story in which there really could be a subtle humor without weakening the narrative. Well, we believe we have found it in this tale, which not only has all of the above-mentioned qualifications, but a fine O. Henry ending thrown in for good measure.

Unfortunately, the “fine O. Henry ending” turns out to be rather uninspired. After Algernon saves Esmerelda from the tiger, the whole story is revealed to have been a dream – not experienced by any of the characters in the narrative, but by a man named John Henry. This fellow has a nagging wife, a bootlegging operation in his basement and a desire for a good night’s sleep, and the world of the future was – it is implied – assembled from his innermost wishes.

“The Chemical Magnet” by Victor Thaddeus

The narrator of this story befriends a reclusive scientist named Schirmanhever, who is conducting experiments at an isolated beachside retreat. The eventual product of Schirmanhever’s labour is an instrument that he describes in loose terms as a chemical magnet: it can extract salt from seawater without using a electricity, making use of “an entirely new principle… a principle as different from any other in the world as, for instance, in the field of vision, the color red is different from the color blue”. The narrator sees the tremendous usefulness of this invention as it is, but Schirmanhever is unsatisfied, and wants to develop a means of extracting individual minerals – such as gold – from the world’s oceans.

The narrator of this story befriends a reclusive scientist named Schirmanhever, who is conducting experiments at an isolated beachside retreat. The eventual product of Schirmanhever’s labour is an instrument that he describes in loose terms as a chemical magnet: it can extract salt from seawater without using a electricity, making use of “an entirely new principle… a principle as different from any other in the world as, for instance, in the field of vision, the color red is different from the color blue”. The narrator sees the tremendous usefulness of this invention as it is, but Schirmanhever is unsatisfied, and wants to develop a means of extracting individual minerals – such as gold – from the world’s oceans.

Schirmanhever later comes to inherit a substantial sum from a wealthy uncle, after which he vanishes. He finally returns four years down the line having perfected his invention, at which point the story becomes a future history: the narrator, speaking after Schirmanhever’s death, outlines the geopolitical ramifications of the chemical magnet, with the inventor becoming “virtually dictator of world affairs” due to his ability to harvest the minerals of the sea. The narrator then describes the final days of Schirmanhever, who had by then decided that his next step would be to improve his magnet further, so that it would be able to extract hitherto unknown chemicals. Later, the inventor – apparently mad – claimed to have discovered the “Secret of Life”; his last act was to produce a green, phosphorescent substance before dropping dead. The laboratory then exploded, and Schirmanhever’s secret died with him.

A slim story that never lives up to its halfway interesting concepts. The theme of an inventor using his device to become a leader in world affairs had been tackled in more detail in “The Moon Metal” by Garrett P. Serviss, printed back in the July 1926 Amazing.

“The Shadow on the Spark” by Edward S. Sears

Dr Milton Jarvis is horrified to learn that his friend, wealthy banker Jim Craighead, has died. Reportedly, the man had perished of shock during surgery after he injured his legs in a train mishap, but Dr Jarvis has trouble accepting this: in life, Craighead always seemed to sturdy and hearty to die in such a manner.

Dr Milton Jarvis is horrified to learn that his friend, wealthy banker Jim Craighead, has died. Reportedly, the man had perished of shock during surgery after he injured his legs in a train mishap, but Dr Jarvis has trouble accepting this: in life, Craighead always seemed to sturdy and hearty to die in such a manner.

And so Jarvis begins discussing the possibility of foul play with one Inspector Craven. Jim Craighead’s nephew and adopted son Ross would have benefitted from his affluent guardian’s death, but seems to idealistic to have stooped to murder. Tessie Prettyman, Ross’s lover and secretary to Jim’s manager, appears innocent to Jarvis – but Craven knows that she has been visiting Piggy Bill Hovey, a suspected drug trafficker.

During the resultant inquest, Dr Jarvis expounds at length on chemistry (complete with diagrams) and concludes that the dead man must have been poisoned with strychnine. This prompts Tessie to break down and reveal all: The criminal Piggy Bill is actually her stepfather, and that she visited him to obtain illicit opiates for Jim Craighead to use as painkillers, as per his request after being turned down by a legitimate druggist.

Tessie also mentions Piggy Bill’s ties to Tarrytown; at this point two men in the court try to escape, only to be arrested. After this development, Jarvis, Craven and Tessie hunt down the Tarrytown drug-dealer (a “hideous looking dwarf”) and find the evidence they need that Piggy Bill had made Tessie as an unknowing accomplice to murder in the hopes of extorting Craighead’s inheritance from her through blackmail.

Like Edwin Balmer and William MacHarg’s Luther Trant stories that had run in Amazing, “The Shadow of the Spark” is a routine detective yarn which uses a scientific concept as a plot device. While Trant’s adventures tended to fall back on lie detectors and similar apparatus, Dr Jarvis plays the forensic investigator by using his knowledge of chemicals to expose the murder.

“Hicks’ Inventions with a Kick: The Automatic Apartment” by Clement Fezandié

This sequel to the “Hicks’ Inventions with a Kick” story in the April 1927 Amazing offers more of the same, with another short tale of ingenious inventions that lead only to disaster.

This sequel to the “Hicks’ Inventions with a Kick” story in the April 1927 Amazing offers more of the same, with another short tale of ingenious inventions that lead only to disaster.

Hicks shows the narrator O’Keefe another of his creations: an apartment so stocked with automatic appliances as to eliminate daily housework almost entirely. In the living room are an automatic vacuum cleaner and furniture that can be arranged by quickly adjusting electro-magnets; in the kitchen, a dishwashing appliance that can load dishes into cupboards. The ceilings can blow dust and cobwebs away by themselves, while the floors that can wash themselves clean using tiny fountains.

Impressed by these inventions, O’Keefe rallies together the former friends of Hicks who have not yet forgiven him for the affair with the automatic dining table. As Hicks shows them around the apartment, everything starts going wrong: the visitors are drenched by the floor fountains, and then covered in a cloud of dust stored by the self-cleaning ceiling. The observers try to escape, only for one of their number to be grabbed by the shoe-blackening device and forced head-first into its mechanism. Meanwhile, the self-arranging furniture blocks the exit, and as the room fills up with water, the hapless visitors find themselves knocked below the surface by the frantic vacuum cleaner. O’Keefe keeps his head above the surface, but has a nasty run-in with an automatic egg-beater.

Eventually the apartment’s safety release activates and all returns to normal. O’Keefe finds that Hicks has already fled – and, as the one who invited the party to the disastrous exhibition, decides that he should do the same.

Discussions

The monthly letters column is once again bustling with activity. John R. Kelley is a satisfied reader, and counts himself as one of many: “you seem to please most of your readers according to the letters you publish. Although “some of them seem to like a certain class such as strictly scientific or almost all imaginative, they all seem to like enough of them to keep on reading the magazine.” E. D. Skinner and Guy Detrick discuss the contest entries that ran in the June issue, and come to the independent conclusion that Cyril G. Wates’ “The Visitation” was the strongest.

Fred W. Fisher, Jr launches a blistering attack on The War of the Worlds, the serialisation of which had been announced in the previous issue. “That story is ROTTEN!” he declares. “I am prejudiced against all of [Wells’] tales, because they are generally disconnected, and he is always having one of this characters come out of his story to scratch his chin or tug his whiskers or expectorate, or something.” On top of this, he expresses disappointment at the conclusion to Garrett P. Serviss’ The Second Deluge: “I do not intend to be bloodthirsty, but it really went against the grain to have several millions of people still alive after Cosmo Versál had made his minute selection—the science of eugenics could hardly succeed, in my opinion, with such a mixed assemblage.”

In contrast, Clifford Kornoelje praises The Second Deluge as “one of the best stories I have ever read” and also requests further tales by Edgar Rice Burroughs, “especially the Martian books. I like stories about interplanetary space, and about the different planets.” The editor provides an amusing response to this statement: “We have sometimes feared that we were giving too many interplanetary stories, but your letter tells us that we have not, and like Oliver Twist you virtually ‘ask for more.’” Humorous editorial responses are a recurring theme this month: when Mike Dukovich sends in a newspaper clipping about a proposed moon rocket, the editor expresses fear that the pilot might hit “a lunar telegraph pole” (“It certainly would be bad for the pole”). One wonders if J. M. Recer, who has a letter in this issue arguing that the editor’s responses can be overly hostile, was placated.

W. St. Helier Hammond states that, after reading the magazine’s letters, “I thank Heaven I wasn’t born clever, for I can read all the stories in your very excellent, entertaining and educational magazine, and really enjoy them” and then, somewhat curiously, adds that “Being a 50-50 mixture of Irish and French and also being of a high psychic nature I often have to close the magazine and put it away because experience has taught me that my dreams will be weird to say the least.” In terms of future reprints, the letter requests H. Rider Haggard’s She.

William W. Johnson states that Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar” and “Mesmeric Revelation” were the only Amazing stories he disliked, although he questions the portrayal of evolution in Burroughs’ The Land that Time Forgot (“he gives the impression that man sprang directly from apes, while the theory as generally accepted is that man and the ape both have a common ancestor”)

Isla Salerno expresses bemusement at some of the details in Bob Olsen’s “The Four Dimensional Roller Press” before noting that the story reminded her of a dream she had as a child: “The janitor of the school I attended and of whom I was rather afraid, seemed to be caught around the chest in a common clothes wringer, and I had to turn that wringer so it would be around his waist so he would be able to breathe. The ghastly agony on that man’s face is with me yet.”

B. Sinclair attacks the letters column of the July issue. “I was immediately struck by the puerility of several of the correspondents. Criticism of such authors as Verne, Poe or Wells, it seems to be, should rest with persons more vested in the literary art than these correspondents appear to be.” Meanwhile, Aaron L. Glasser devotes an entire letter to attacking an earlier correspondent who wrongly attributed Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World to H. G. Wells.

Raymond Stimps throws aside that old chestnut of scientific plausibility (“We cannot judge such things by scientific facts that are true today because we of today do not know all scientific possibilities and probably never will”) but does question the assumption that aliens would look like humans. John Pierce offers a lengthy commentary on the ecology of Murray Leinster’s “The Mad Planet” and concludes that, contrary to the story, a rise in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would not cause insects to grow in size.

John Mackay states that he enjoys the magazine’s letters column: “I am pleased to note what a large number of young men are interested in science.” This observation is backed up by a letter from 15-year-old reader Kenneth L. Mueller, who defends “Through the Crater’s Rim” by A. Hyatt Verrill from readers who objected to story’s man-eating plant; he sees this concept as a reasonable extrapolation from insect-eating plants that exist in reality. Another youngster this month is 14-year-old Everett Beran, who finds fault in the illustration to Wells’ “Under the Knife” (“the character of the story finds himself going through the air with neither hands not feet, but in the picture at the beginning of the story he has both hands and feet. How can you explain this?”

Finally, John M Stern offers praise for the magazine in general, expressing particular fondness for “stories which deal in radio and later [sic] day science”, such as G. McLeod Winsor’s Station X.

(Editor’s personal note: Thus FR Paul cover is by far my favorite: Posters of this and other FR Paul Amazing Stories covers are available for purchase in our store. I have two of these on my office walls.)

Read My Profile