A group of men cluster around a woman as she lies tucked up in bed. On a bedside table is an elaborate electrical apparatus, complete with battery, cables and brass dial. The woman appears to be speaking into part of the device, held over her mouth by a seated man; another man holds a different part of the apparatus in his own mouth while writing on a notepad. What is happening? Are they testing out a telephone? Or is it some sort of recording device?

A group of men cluster around a woman as she lies tucked up in bed. On a bedside table is an elaborate electrical apparatus, complete with battery, cables and brass dial. The woman appears to be speaking into part of the device, held over her mouth by a seated man; another man holds a different part of the apparatus in his own mouth while writing on a notepad. What is happening? Are they testing out a telephone? Or is it some sort of recording device?

It was April 1927, and Amazing Stories was celebrating its first anniversary by intriguing its readership with a new set of scientific marvels.

Hugo Gernsback’s editorial for the month is entitled “The Most Amazing Thing (In the Style of Edgar Allan Poe”). This is the story of an alien ruler, the all-powerful Supremental, meeting with an explorer who has returned from “the Third Planet of the Sixth Universe”. The explorer describes the weird denizens of this world, a species whose soft body is equipped with tentacle rods and topped with an oval appendage containing various sensory organs. These beings live in cubicles, use a crude form of fuel derived from fauna and flora, and have the weird habit of periodically exterminating each other by the thousands for no discernible reason. The alien king immediately dismisses the idea of such an absurd species ever existing.

Having devoted his editorial space to a fictional exercise of his own, Gernsback hands the microphone to his latest batch of contributors…

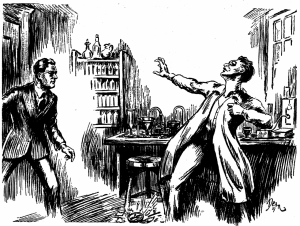

“The Plague of the Living Dead” by A. Hyatt Verrill

A biologist, Dr Gordon Farnham, announces that he has come across a method of extending human life by centuries. His claims are met with such widespread ridicule that he retires to the small island of Abilone, where he can continue his experiments in peace.

A biologist, Dr Gordon Farnham, announces that he has come across a method of extending human life by centuries. His claims are met with such widespread ridicule that he retires to the small island of Abilone, where he can continue his experiments in peace.

While trying to perfect his serum, Farnham conducts an experiment on the body of a dead guinea pig; to his surprise, the animal begins moving. He has discovered not only a means to prolong life, but a means to raise an organism from the dead. On top of this, he finds that the animals injected with the serum become immune to the effects of poisonous gas and drowning.

When he realises the implications of his discovery, he begins roaring “with truly maniacal laughter”. But even in this state he is disturbed by some of the results of the serum: he decapitates a rabbit and the creature survives, its body continuing to hop around while its severed head also shows signs of life.

Then the island’s volcano erupts, destroying the laboratory. Undeterred, Dr Farnham takes his surviving serum and uses it on some of the islanders who perished in the eruption.

The resurrected humans then begin attacking people in a frenzy. Farnham initially speculates that they are still panicking over the volcanic eruption, but he then comes to a more uncomfortable realisation: that his serum can restore the body, but not the mind. Contrary to his materialistic philosophy, he wonders if these resurrected people are lacking the souls of the living. He is forced to look on, helpless, as his indestructible creations continue to attack the locals.

A relief party and police arrive at the village after hearing of the mayhem, only to be driven back by the living dead. With Farnham acting as advisor, the authorities continue their attempts to wipe out the immortals, but find no method of destroying creatures that can survive any injury – and even reproduce. Eventually, Farnham hits on the idea of building a Jules Verne-like cannon into the volcano and launching the Living Dead into space.

Right down to its title “The Plague of the Living Dead” has obvious similarities to the zombie films such as Night of the Living Dead that developed decades later, and is well worth a look from fans of that genre. The walking corpses imagined by A. Hyatt Verrill have some unusual traits that set them apart from subsequent zombies – in particular, their ability to repair themselves using each other’s severed body parts, patching up their wounds with whatever pieces are left lying around. In doing so they create such hideous beings as a head attached to two arms and a leg, which runs around like a spider; or a limbless torso with two extra heads growing from the stumps of its severed arms. Although the beings can survive without heads, they somehow find heads desirable, and begin decapitating each other so as to obtain additional heads for their bodies.

Any horror filmmaker looking for an unusual twist on the zombie genre should find plenty of inspiration in this largely-forgotten story.

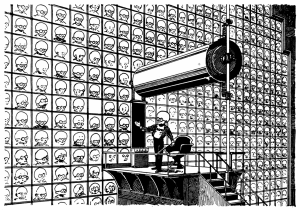

“John Jones’s Dollar” by Harry Stephen Keeler

This humorous story begins in the year 3221 Humanity has abandoned its “crude multi-reduplicative system of nomenclature” and people now go under such monikers as B262H72472476Male. Money has been abolished, and the one true unit of value is considered to be the Psycho-Erg: a combination of the Psych (“the unit of aesthetic satisfaction”) and the Erg (“the unit of mechanical energy”). Mankind’s morphology has changed, leading to a race of squat, bulbous-headed individuals.

This humorous story begins in the year 3221 Humanity has abandoned its “crude multi-reduplicative system of nomenclature” and people now go under such monikers as B262H72472476Male. Money has been abolished, and the one true unit of value is considered to be the Psycho-Erg: a combination of the Psych (“the unit of aesthetic satisfaction”) and the Erg (“the unit of mechanical energy”). Mankind’s morphology has changed, leading to a race of squat, bulbous-headed individuals.

A university professor, lecturing his class through an array of television-like “Visaphones”, gives them a history lesson…

In 1921, a hardened socialist named John Jones made a deposit of a single dollar to his bank, stipulating that interest of 3% would be compounded every year, and the final sum eventually inherited by his fortieth descendent. In 1931, the account contained $1.34; in 2021, $19.10; in 2121, £364; in 2221, $6920. By the end of the twenty-seventh century, the account had reached a ten figure sum.

As he describes this story, this teacher of the future touches upon such historical events as the weakening and collapse of socialism; the rise of eugenics, leading to names being replaced with numbers; the lengthening of human lifespans using gamma rays; the development of anti-gravity technology, and the ensuing colonisation of the solar system; the invention of a process whereby corpses can be recycled into food, ending world hunger; and the destruction of the Moon, so as to facilitate interplanetary travel.

Finally, in the thirtieth century, John Jones’ thirty-ninth descendant J664M42721Male began making plans to have a baby who would inherit the sum of $6,310,000,000,000. This, it turned out, would be almost the total wealth of the entire solar system.

But then something unexpected happened: J664M42721Male split with his lover and died childless. With no other heir, the Interplanetary Government took possession of the money, ending all private property. John Jones’ dream of a socialist future had come to pass.

Its thin plot a variation on the old wheat and chessboard problem, “John Jones’s Dollar” recalls some of Hugo Gernsback’s own fiction by using a token narrative as a means of taking the reader on a trip through the future, touching upon various potential future developments without integrating them into the plot.

“The Remarkable Case of Davidson’s Eyes” by H. G. Wells

The story begins with the protagonist Bellows working in a laboratory. After the building is struck by lightning, Bellows’ cohort Sidney Davidson begins staggering around and knocking over equipment. Bellows initially believes that Bellows has gone blind, but it turns out that the man can see – he just happens to be seeing a completely different location, and believes himself to be on a beach. From his point of view, Davidson has been mysteriously transported, and can feel himself stumbling into equipment that he cannot see.

The story begins with the protagonist Bellows working in a laboratory. After the building is struck by lightning, Bellows’ cohort Sidney Davidson begins staggering around and knocking over equipment. Bellows initially believes that Bellows has gone blind, but it turns out that the man can see – he just happens to be seeing a completely different location, and believes himself to be on a beach. From his point of view, Davidson has been mysteriously transported, and can feel himself stumbling into equipment that he cannot see.

Davidson remains in this state over the following weeks. He describes the island location that he sees, including details such as penguins and a ship. He even describes heading underwater in his vision and witnessing marine life. Over time, however, the visions fade and his ordinary sight returns.

Years later, Davidson sees a photograph of the very ship that he had witnessed in his vision. Speaking to a former member of the ship’s crew, he learns that it had indeed visited an island inhabited by penguins, identical to the one he had apparently hallucinated.

Although not one of Wells’ more substantial stories, “The Remarkable Case of Davidson’s Eyes” is nonetheless a striking and convincing portrayal of what is now known as remote viewing. The story was first published in 1895; two years later Wells explored similar themes to greater effect in “The Crystal Egg”, which had already been reprinted in Amazing.

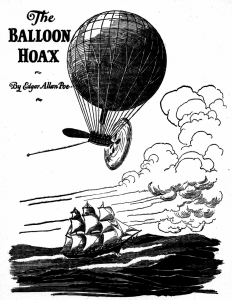

“The Balloon-Hoax” by Edgar Allan Poe

Having previously reprinted “The Moon Hoax”, Amazing returns to the well of literary tall tales with a famous hoax from Edgar Allan Poe. Originally published in the New York Sun in 1844, Poe’s narrative was presented as a factual news report, but is in fact pure fiction.

Having previously reprinted “The Moon Hoax”, Amazing returns to the well of literary tall tales with a famous hoax from Edgar Allan Poe. Originally published in the New York Sun in 1844, Poe’s narrative was presented as a factual news report, but is in fact pure fiction.

The article begins by announcing that “The air, as well as the earth and the ocean, has been subdued by science, and will become a common and convenient highway for mankind.” It goes on to claim that a crew of eight men have successfully traversed the Atlantic in a balloon, taking only seventy-five hours to do so. After describing the technical details of the balloon, the article presents an account purportedly lifted from the joint diary of two crew members, Monck Mason and Harrison Ainsworth. Here, the pair make some observances about their trip, amongst other things noting an optical illusion that makes the sea appear concave, before describing their arrival at their destination.

The brief tory covers ground that would later be explored in more detail by Jules Verne.

“The Man in the Room” by Edwin Balmer and William B. MacHag

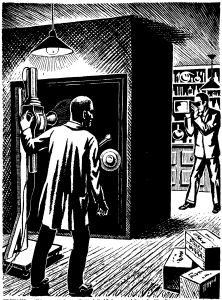

Another tale of the science-minded detective Luther Trant. It begins with Trant complaining about the primitive nature of modern crime-detection, and the importance of lie-detection equipment; no sooner has he finished his speech [does] he become embroiled in yet another mystery.

Another tale of the science-minded detective Luther Trant. It begins with Trant complaining about the primitive nature of modern crime-detection, and the importance of lie-detection equipment; no sooner has he finished his speech [does] he become embroiled in yet another mystery.

This time, Trant ends up investigating the death of one Professor Lawrie, whose body was found in his laboratory. It initially appears that Lawrie committed suicide after embezzling funds from his university. However, Trant deduces that the man was actually murdered, He then produces a small list of possible culprit and, citing the theories of Freud, subjects his suspects to a word-association test. Through this method, he exposes the guilty party.

Compared to the Luther Trant stories previously reprinted in Amazing, “The Man in the Room” does a slightly better job of marrying its scientific backdrop to its detective plot.

“The White Gold Pirate” by Merlin Moore Taylor

A criminal known only as the Platinum Pirate is abroad, stealing platinum from shipments and selling it on the black market. Somehow, he manages to do so without breaking the seals on the vault. The police are baffled, until scientist Goodwin and detective Barry put their heads together and solve the crimes. The robberies turn out to be inside jobs: the pirate himself is a former chemist at a platinum plant, while his latest crime was carried out with the aid of the vault’s electrician.

A criminal known only as the Platinum Pirate is abroad, stealing platinum from shipments and selling it on the black market. Somehow, he manages to do so without breaking the seals on the vault. The police are baffled, until scientist Goodwin and detective Barry put their heads together and solve the crimes. The robberies turn out to be inside jobs: the pirate himself is a former chemist at a platinum plant, while his latest crime was carried out with the aid of the vault’s electrician.

“The White Gold Pirate” is another scientific detective story, and a more satisfying example of mixed genre elements. Again, the crime being exposed through technological means: the heroes use a lie detector on their captive, examine the vault with an X-ray device, and also make use of radio. But where the Luther Trant stories sgenerally graft sequences of this type onto conventional detective yarns, Taylor takes things further by weaving science and technology throughout the entire narrative. The criminals have access to gadgets of their own, including a device used for removing and replacing the vault’s wax seals without breaking them. Meanwhile, the very subject of their crime has scientific connections, as the story spends time describing how platinum is used in laboratories.

“The Automatic Self Serving Dining Table” by Clement Fezandié

Another one of the “wacky inventor” stories periodically printed in Amazing as comic relief, this time the first in a new series entitled “Hicks’ Inventions with a Kick”. The story is credited to Henry Hugh Simmons; this was in fact a pen-name used by Clement Fezandié, whose “Dr. Hackensaw’ Secrets” series had previously appeared in Amazing.

Another one of the “wacky inventor” stories periodically printed in Amazing as comic relief, this time the first in a new series entitled “Hicks’ Inventions with a Kick”. The story is credited to Henry Hugh Simmons; this was in fact a pen-name used by Clement Fezandié, whose “Dr. Hackensaw’ Secrets” series had previously appeared in Amazing.

Crotchety narrator O’Keefe bumps into an annoying old schoolchum, Hicks. He initially tries to brush off his acquaintance, but becomes intrigued when Hicks claims to have invented a mechanised table that can prepare and serve food itself, eliminating the need for cooks or waiters.

O’Keefe attends a demonstration of the device, along with his aunt Zelinda and Hicks’ own family members. The mechanical table turns out to be a disaster, launching plates, bottles, pressurised tomato soup and chunky portions of meat in all directions until the irate diners are coated in food.

The Land that Time Forgot by Edgar Rice Burroughs (part 3 of 3)

Having run The Land that Time Forgot and The People that Time Forgot, Amazing concludes the series with Out of Time’s Abyss. Where the first part focused on dinosaurs and the second on cave people, the third makes the lost island of Caspak still more fantastic by introducing a race of winged humanoids called the Wieroo.

Having run The Land that Time Forgot and The People that Time Forgot, Amazing concludes the series with Out of Time’s Abyss. Where the first part focused on dinosaurs and the second on cave people, the third makes the lost island of Caspak still more fantastic by introducing a race of winged humanoids called the Wieroo.

Also making his debut is Bradley, still another explorer who has found himself in Caspak. He tangles with the Wieroo and their evil religious leader, falls in love with a beautiful cavewoman, and generally gets into all of the scrapes to be expected from a self-respecting Edgar Rice Burroughs hero. The story comes full circle when Bradley comes upon the U-boat that took the hero of the first instalment to Caspak – along with the German villain, Baron von Schoenvorts.

Discussions

In this month’s letters column, J. P. McCague declares that “There is a difference between fairy tales and real scientific fiction”, commenting that “It would gratify me immensely to see ‘intelligent lobsters’ and ‘man-eating trees,’ together with similar hokum, missing from Amazing Stories” (Gernsback pleads that such material is no more absurd than Gulliver’s Travels). Otto Lindemann offers criticism of The Second Deluge, pointing out that the owner of the ark buys the last horses in England to place on board, even though there are horses in Colorado (the editor explains that the character was presumably unaware of the American horses at the time).

Arthur Levine asks why the carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere in Murray Leinster’s “The Mad Planet” has caused insects to grow to vast size, but not humans (the editor explains that “carbon dioxide gas would tend to increase the vigor of plant life, but would have exactly the opposite effect on the animal system”, although “what would favor plant growth might operate to favor insect growth”).

An anonymous reader sends in an irate and rather over-literal deconstruction of Fitz-James O’Brien’s fantasy story “The Diamond Lens” (“why should animalicules living in a molecule, be discommoded by the evaporation of the drop of water? […] Also how can a man see, with no aid save that of a diamond lens, that which we are unable to see because our eye is too course?)

In contrast to the above complaints, Eric R. Gage gives a favourable assessment of the magazine, dismissing its detractors and declaring that Hugo Gernsback knows best what stories to publish.

Amusingly, a reader identified as R. S. appears to have mistaken an advert promoting a self-help guide for one of the magazine’s short stories: “‘They Called Me a Human Clam, But I Changed Almost Overnight’ is also good”, he writes; “I often wonder what would happen if the Hard-Working-Young-Man-Who-Never-Seemed-to-Get-Anyplace studied fourteen or sixteen minutes a day instead of the accepted fifteen.”

Last of all, E. H. Hardy praises the magazine for printing the work of earlier writers such as Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, and expresses a desire to see H. Rider Haggard published as well

And finally…

The issue features another poem by Leland S. Copeland, entitled “Superstar”:

Alpha of Orion, mammoth of the sky

Dropping gold at evening, sparkling red and high;

Blinking light at billions,

Vast as suns by millions;

Far among the stars and rich in latent worth—

Greetings from a solar atom, wrinkled little earth!

Airy in your substance, hardly there at all,

You are moving madly—heed some secret call.

Woven in your glories,

Doze uncounted stories.

Life and hope and death, with love and loss and tears,

Sleep within your vapors, wait the throbbing years.