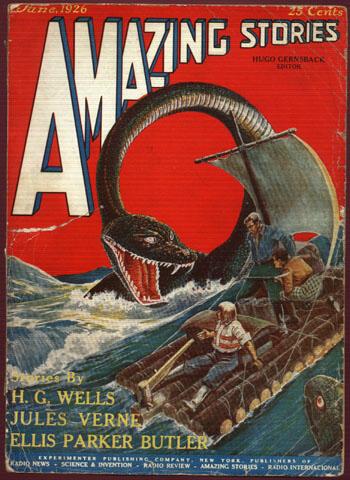

A raft bearing three men is tossed about on a turbulent sea. The water around them is being churned by an enormous plesiosaurus, which bears its teeth at the crew of the raft. On the other side of the vessel is the head of a second sea-beast: a Scylla and Charybdis for the age of palaeontology. It was June 1926, and readers across America were ready for another round of Amazing Stories.

A raft bearing three men is tossed about on a turbulent sea. The water around them is being churned by an enormous plesiosaurus, which bears its teeth at the crew of the raft. On the other side of the vessel is the head of a second sea-beast: a Scylla and Charybdis for the age of palaeontology. It was June 1926, and readers across America were ready for another round of Amazing Stories.

In the issue’s editorial, editor Hugo Gernsback continues to develop his concept of “scientifiction”. Having previously named Edgar Allan Poe as the father of the genre, Gernsback digs further back into history to find some of the minds who laid the groundwork: these include Leonardo da Vinci (whose theoretical machines “would have done credit to a Jules Verne”) and Roger Bacon. He also discusses an appropriate label for the magazine’s letter-writing readership: “shall we call them ‘Scientifiction Fans’?” he asks.

Well, whatever they should be termed, here is what scientifiction fans of 1926 were in for with issue 3 of Amazing Stories…

“The Coming of the Ice” by G. Peyton Wertenbaker

“The Coming of the Ice” has the distinction of being the first original story bought by Amazing, which had previously relied on reprints. The teenage author was no stranger, however, as the magazine had previously run his tale “The Man from the Atom”.

“The Coming of the Ice” has the distinction of being the first original story bought by Amazing, which had previously relied on reprints. The teenage author was no stranger, however, as the magazine had previously run his tale “The Man from the Atom”.

It is 1930, and surgeon Sir John Granden has discovered a method of granting eternal life simply by rearranging the organs of the body. Protagonist Carl Dennell undergoes this surgery, despite its heavy cost: the operation renders its subject impotent, and in the process, “deprives one of all the things that go with sex, all love, all sense of beauty, all feeling for poetry and the arts.” All that remains are “selfish emotions, that are necessary to self-preservation… One becomes an intellect, nothing more”.

Dennell’s decision leaves his lover Alice distraught. She insists upon undergoing the same treatment, so that she can still be with her immortal beloved. Dennell ponders whether love can truly exist without emotion: “Is love something entirely of the flesh, something created by an ironic God merely to propagate His race? Or can there be love…between two cold intellects?”

He is never to find out, however. After recovering from the successful operation, he learns that both Granden and Alice were killed in a car accident. He is initially wrought with anguish, but over time, such emotions fade away. He devotes his extended life to studies, in the hopes of someday commanding the world: “I felt myself a super-man”, he tells us, twelve years before Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s similarly-named hero hit the newsstands.

But soon, Dennell learns the full cost of his condition. Humanity develops around him, and he finds himself a relic of the twentieth century, hopelessly outmoded by the post-Einstein scientists of the twenty-second. When Venusians invade Earth, only to be repelled by humanity’s superior technology, Dennell feels more affinity with the aliens than with his fellow race.

He lives to see mankind evolve into a new species, with “huge brains and tiny shrivelled bodies”; these people of the future are even colder-hearted than Dennell, who watches aghast as they kill off “all the perverts, the criminals, and the insane”. Then an ice age arrives, and wipes out this physically weakened race. The story ends with Dennell the last inhabitant of Earth, his old emotions finally returning as he escapes into memories of his beloved Alice while the cold creeps up on him.

“The Coming of the Ice” covers similar ground to Wertenbaker’s earlier “The Man from the Atom”, both stories concerning a character who, through a scientific experiment, traverses vast periods of time and must face the loneliness of eventual separation from the rest of humanity. It also has similarities to certain works by H. G. Wells, most obviously The Time Machine – although it is The Sleeper Awakes that the narrative actually namechecks.

At the same time, intentionally or not, Wertenbaker was working partially within the older tradition of Gothic literature. Dennell’s decision to sacrifice emotions in exchange for eternal life is an SF spin on the Faust theme, while the mixed blessing of immortality is a Gothic standard from Melmouth the Wanderer through to modern vampire fiction. The pervading romantic anguish and aesthetic of picturesque decay – here occurring on a global scale, as the ice age leaves “great hungry, haggard skeletons of cities, shrouded in banks of snow, snow that the wind rustled through desolate streets where the cream of human life once had passed in calm security” – is also quintessentially Gothic.

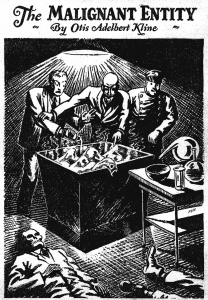

“The Malignant Entity” by Otis Adelbert Kline

Albert Townsend, a chemist with “queer theories about creating life from inert matter”, is killed under mysterious circumstances: all that is left of him is a skeleton. Protagonists Mr. Evans and Dr. Dorp are called in to investigate, and realise that whatever killed Townsend still poses a threat when a police officer accompanying the two men is also reduced to mere bones.

Albert Townsend, a chemist with “queer theories about creating life from inert matter”, is killed under mysterious circumstances: all that is left of him is a skeleton. Protagonists Mr. Evans and Dr. Dorp are called in to investigate, and realise that whatever killed Townsend still poses a threat when a police officer accompanying the two men is also reduced to mere bones.

First published in Weird Tales two years previously, “The Malignant Entity” is a mystery story with Dorp and Evans serving as the Holmes and Watson of a new scientifiction age. The killer turns out to be an organism created by Townsend, single-celled but visible to the naked eye, and capable of stripping a creature to the bone.

Despite being grounded in the scientific world of microbiology, Kline’s story has a metaphysical streak. Dorp initially declares that naturally-occurring cells of protoplasm possesses “a mind—a soul—a something that makes it a living individual”, while Townsend’s synthetic protoplasm lacks this quality. Instead, his creation is “a malignant entity governed solely by the primitive desire for food and growth with only hatred of and envy for those more fortunate natural creatures around it.”

At the start of the story, meanwhile, the main characters discuss ghosts and spiritualism, touching upon the theories of the physicist and psychical researcher Oliver Lodge. This foreshadows the narrative’s bizarre conclusion: the cell turns out to be possessed by the spirit of Immune Benny, a suspected murderer who died while lodging with the Townsend family, as is evidenced when it briefly takes on the appearance of his face.

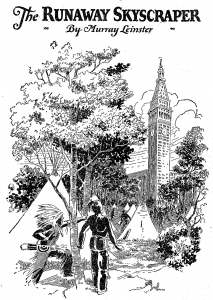

“The Runaway Skyscraper” by Murray Leinster

Reprinted from a 1919 Argosy issue, “The Runaway Skyscraper” introduces us to a pair of dissatisfied characters: Arthur Chamberlain, who is struggling with his career; and his secretary Estelle Woodward, who is struggling to find a boyfriend. They are thrown together into a strange adventure when the world outside of their skyscraper – people, cars, even the sun – begins running backwards at high speed (Wells’ “The New Accelerator” in the first issue gave us slow-motion; here, Murray Leinster gives us rewind).

Reprinted from a 1919 Argosy issue, “The Runaway Skyscraper” introduces us to a pair of dissatisfied characters: Arthur Chamberlain, who is struggling with his career; and his secretary Estelle Woodward, who is struggling to find a boyfriend. They are thrown together into a strange adventure when the world outside of their skyscraper – people, cars, even the sun – begins running backwards at high speed (Wells’ “The New Accelerator” in the first issue gave us slow-motion; here, Murray Leinster gives us rewind).

When the city outside is replaced with log cabins, Arthur realises that they are traveling through time – or, as he puts it, “there has been an earthquake, and the ground has settled a little with our building on it, only instead of settling down toward the centre of the earth, or side-ways, it’s settled in this fourth dimension.” Eventually, the time-travelling skyscraper comes to a stop in the pre-Columbian era of American history…

This is another story that namechecks Wells, as Arthur mentions The Time Machine while explaining time travel to Estelle. Leinster in fact emulates Wells at his most whimsical, as the story is not afraid to be silly. We have the obviously absurd idea of an earthquake causing the skyscraper to fall through a hole in time; we have Arthur’s initial theory that people outside are walking backwards because Earth’s rotation has been reversed; and we have a humorous scene where Arthur’s watch suddenly explodes – the inverting of time having caused it to become too tightly wound-up.

Once the characters arrive in the past, meanwhile, the story becomes a Robinson Crusoe-like survivalist narrative. This is nothing new for SF, as Jules Verne had already explored the potential of combining scientific speculation with the Crusoe genre; but with its celebration of the pioneer spirit, “The Runaway Skyscraper” could be seen as a specifically American take on the theme.

The building has a few commodities that prove useful: the security guards’ guns serve as hunting equipment, while various trinkets are traded with the local Native Americans. The blossoming love between Arthur and Estelle grows to overshadow the group’s attempts at survival, however. The story ends with the protagonists nudging the skyscraper back into the present day by activating a geyser underneath it – a conclusion which again recalls Verne, who could be similarly abrupt in getting his heroes out of trouble.

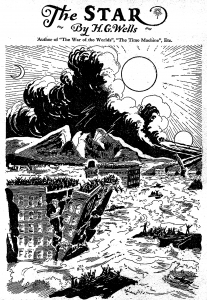

“The Star” by H. G. Wells

Published in 1897, “The Star” is an apocalyptic story. It begins with an unknown planet hitting Neptune; this converts both spheres into a burning mass on a collision course with the sun. Earth, it turns out, is in the middle of this course.

Published in 1897, “The Star” is an apocalyptic story. It begins with an unknown planet hitting Neptune; this converts both spheres into a burning mass on a collision course with the sun. Earth, it turns out, is in the middle of this course.

One of Wells’ skills was the ability to craft a strong character sketch in only a few lines. This talent is evident in “The Star”, where each character appears only briefly in the narrative as Wells’ narrator casts an eye across the Earth during its final days, making a brisk survey of humanity from England to South Africa.

At first, only the scientific community notices the disorder in the heavens. When the destruction of Neptune becomes visible from Earth, many people begin to react with superstition: they speak of “the wars and pestilences that are foreshadowed by these fiery signs in the Heavens” and listen to “the tolling of the bells in a million belfry towers and steeples, summoning the people to sleep no more, to sin no more, but to gather in their churches and pray.” Despite being told that the world is doomed, however, most of humanity continues as usual, with many people outright scoffing at the idea of the planet’s impending demise.

And then the star arrives, bringing earthquakes, storms and floods. Volcanoes erupt, jungles burn, the sea whips and churns. Earth survives, if only barely, as the star passes, leaving the human race to take stock of the changed world.

As a relatively early example of apocalyptic SF, “The Star” showcases the more poetic side to Wells’ writing, creating a sense of beauty in the cataclysmic. The story ends with a group of Martian astronomers observing the event and noting the geographical changes wrought upon Earth’s surface, while making no mention of humanity’s devastation. “Which only shows how small the vastest of human catastrophes may seem,” notes Wells’ narrator, “at a distance of a few million miles.”

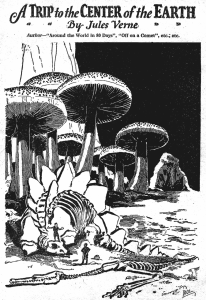

A Trip to the Center of the Earth by Jules Verne

In this continuation of Verne’s novel, Professor Hardwig and company continue their descent into the Earth via an Icelandic volcano. Along the way, they discover a range of life that has long gone extinct on the surface world: first, a forest of enormous mushrooms; then, a sturgeon-like fish; and after that, a plesiosaur and ichthyosaur that do battle with each other as the explorers sail a raft across a subterranean ocean.

In this continuation of Verne’s novel, Professor Hardwig and company continue their descent into the Earth via an Icelandic volcano. Along the way, they discover a range of life that has long gone extinct on the surface world: first, a forest of enormous mushrooms; then, a sturgeon-like fish; and after that, a plesiosaur and ichthyosaur that do battle with each other as the explorers sail a raft across a subterranean ocean.

Finally, just before the second installment of the story comes to a close, they come across preserved bodies of primitive humans, raising the question of what kind of people they will encounter underground. Alongside all of these discoveries are tense moments involving loss of direction and a dangerously low water supply; even in this dubious translation, Verne’s skill at mixing scientific elucidation with a gripping yarn is apparent.

Shorter stories

Amazing Stories #3 also contains a batch of brief, humorous tales themed around inventions and the (often eccentric) men responsible for them.

Amazing Stories #3 also contains a batch of brief, humorous tales themed around inventions and the (often eccentric) men responsible for them.

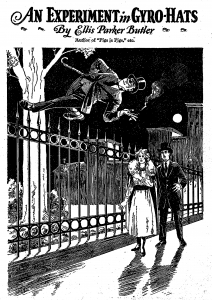

Fairly typical is Ellis Parker Butler’s “An Experiment in Gyro-Hats”, a 1910 story from Hampton’s Magazine. The main character is a self-absorbed hat salesman who believes it wasteful that top hats contain so much empty space: “When a shoe is on, it is full of foot, and when a glove is on, it is full of hand; but a top hat is not, and never can be, full of head, until such a day as heads assume a cylindrical shape”.

Seeing that his daughter’s boyfriend Walsingham walks with a stagger, the hatter is hit by inspiration: he will construct a top hat containing a gyroscope. Just as a gyroscope can keep a monorail car balanced, a gyro-hat could keep its wearer balanced; and to test his new invention, the hatter gets roaring drunk (“I had a great longing to hold my wife’s hand…as she should not let me kiss her, I felt the need of kissing the waiter”). Although the gyro-hat does not work entirely as planned, it manages to cure Walsingham of his affliction – largely due to some quick-thinking from the hatter’s daughter.

Walsingham’s stagger is not from drinking, as the hatter had assumed, but from an ill-fated device called the Gribbs Mule Reverser. The idea that inventions can do as much harm as good also turns up in Jacque Morgan’s “Mr. Fosdick Invents the ‘Seidlitzmobile’”, part of the “Scientific Adventures of Mr. Fosdick” series from Modern Electrics. Inventor Jason Q. Fosdick shows a businessman his latest creation: a car that runs on Seidlitz powders (a laxative that was available on the market at the time), being propelled by gas resulting from the chemical reactions of the powder. Fosdick predicts that his creation will revolutionise transport – “The horse is bound to become as extinct as the dodo” – but the meddling of an unhelpful drugstore clerk leads to a nasty mishap for everyone concerned.

Walsingham’s stagger is not from drinking, as the hatter had assumed, but from an ill-fated device called the Gribbs Mule Reverser. The idea that inventions can do as much harm as good also turns up in Jacque Morgan’s “Mr. Fosdick Invents the ‘Seidlitzmobile’”, part of the “Scientific Adventures of Mr. Fosdick” series from Modern Electrics. Inventor Jason Q. Fosdick shows a businessman his latest creation: a car that runs on Seidlitz powders (a laxative that was available on the market at the time), being propelled by gas resulting from the chemical reactions of the powder. Fosdick predicts that his creation will revolutionise transport – “The horse is bound to become as extinct as the dodo” – but the meddling of an unhelpful drugstore clerk leads to a nasty mishap for everyone concerned.

“There was quite a demand for ‘Dr. Hackensaw’s Secrets’”, wrote Hugo Gernsback in his editorial for issue 2, and so this series by Clement Fezandié – which had been running in Science and Invention since 1921 – continued in Amazing. In “Some Minor Inventions”, Hackensaw shows a series of gadgets to an enthusiastic youngster named Pep Perkins. These include a voice-operated typewriter; a mechanical judge; and an implement for measuring a woman’s age. The story is a curious mixture of whimsy and a sort of proto-hard-SF meticulousness in regards to the workings of the machines.

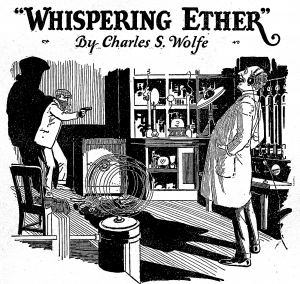

In Charles S. Wolfe’s “Whispering Ether”, the humorous overtone is offset by a more ominous undertone. The narrator is a safecracker, contracted to steal a formula from a scientist named Proctor. The scientist catches him in the act, however; alternating abruptly between hostility and geniality, Proctor decides to give him a demonstration of a newly-invented mind reading device “based on the electro-magnetic wave and the conducting ether theories.” As Proctor explains, the machine works in a similar way to a radio receiver, but the waves it picks up are broadcast by the human brain. Proctor is justly proud of his invention: “Our friend DeForest thinks that he has a monopoly on ultra-sensitive detectors. Proctor’s detector is to the audion what a stop watch is to a wheel barrow!”

In Charles S. Wolfe’s “Whispering Ether”, the humorous overtone is offset by a more ominous undertone. The narrator is a safecracker, contracted to steal a formula from a scientist named Proctor. The scientist catches him in the act, however; alternating abruptly between hostility and geniality, Proctor decides to give him a demonstration of a newly-invented mind reading device “based on the electro-magnetic wave and the conducting ether theories.” As Proctor explains, the machine works in a similar way to a radio receiver, but the waves it picks up are broadcast by the human brain. Proctor is justly proud of his invention: “Our friend DeForest thinks that he has a monopoly on ultra-sensitive detectors. Proctor’s detector is to the audion what a stop watch is to a wheel barrow!”

Using the device, the burglar hears what appears to be a German plotting an act that will send Europe into conflict (we are informed that this incident occurred in July 1914, before Germany declared war on Russia). Fleeing in a panic, the safecracker accidently sets off an explosion which destroys the laboratory; both men survive, but the mind machine is presumably lost to time.

Amazing Stories #3 offers an interesting balance. On the one hand, it features two visions of the apocalypse and a macabre ghost story; on the other, we have a set of light-hearted “wacky inventor” stories. The editorial team were certainly keen on showcasing a broad range of scientifiction.