Is today a day of the week with a “y” in it?

Then, yes! It’s a great day to talk about Aldous Huxley’s towering creation. The man himself seems to have been a bit of a pig. I always get him mixed up in my head with his grandfather Thomas Huxley, “Darwin’s Bulldog,” who was the Christopher Hitchens of his day, except not as funny. Aldous went nearly blind in his youth, then moved to California and became a vegetarian. In later life he did a lot of drugs, went right off the rails, and died of cancer on the same day as JFK was assassinated. Poor man. But he left us Brave New World as well as some other not-as-good books, and every time I think about BNW I think, “Holy crap, did he have a crystal ball or something?”

Maybe it was all that LSD.

“The most important Manhattan Projects of the future will be vast government-sponsored enquiries into what the politicians and the participating scientists will call ‘the problem of happiness.'”

Hodgkinson: “In other words, the problem of making people love their servitude.”

Look. Am I trying to get you to storm into the office with a pitchfork and start inflicting a bit of truth, beauty, pain, and unhappiness on the modern world? (Anything would be more beautiful than those inspirational slogan posters. Even a hole in the sheetrock with the sun shining in.) Of course not! For one thing, you don’t have a pitchfork. I don’t either. What’s the nearest thing you’ve got to one? We have the baseball bat, of course, that we keep for zombies, in the closet with the 50-kilo sacks of rice and the radiation counter. But honestly, a baseball bat isn’t gonna make much of a dent in the gross national happiness statistics.

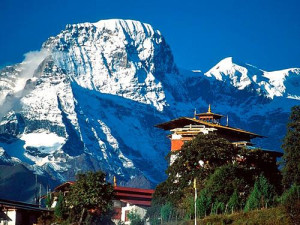

Huxley’s miserific vision started coming true in Bhutan, of all places. The country’s Gross National Happiness Commission (GNHC) divides happiness into four “pillars” and nine “domains.” This is clearly an endeavor informed by Himalyan Buddhism and in fact the GNHC is at pains to point out that “GNH in Bhutan is distinct from the western literature on ‘happiness’.” Which is all well and good, except that according to the GNHC, “true abiding happiness” consists in “realizing our innate wisdom and the true and brilliant nature of our own minds.”

Which is where the GNHC and I part company. The true and brilliant nature of our own minds, fully realized, is likelier to lead us to the gulag than to earthly bliss.

But all right, all right: unfortunate verbiage aside, the Bhutanese are really aiming at something closer to what we would call living within our means, and the GNHC’s website is endearingly amateurish, suggesting that the country is in no danger of morphing into a technocratic Brave New World anytime soon. (Sample “In the News” item: “Which gives the staff less than a ye fake louis vuitton handbags ar to figure out how to rig a boatmounted camera.”)

Where the concept has been picked up in the West it tends to be called “well-being,” in an attempt to head off the point-and-laugh brigade. An exception is the forthrightly named Happy Planet Index, which seeks to measure happiness in terms of ecological footprint and self-esteem. Take their (deeply flawed) survey and find out how happy the technocrats think you are! My personal Happy Planet Index (HPI) was 46.6, which is a crock of the proverbial because I am happy every day.

Science fiction has an unhappy relationship with utopias. Lots of modern sf writers have technocratic leanings. One can see the full panoply in, for instance, the Benford brothers’ new anthology, Starship Century. I myself often fume that we’d have a functioning space program, dammit, if only the really smart people were running the show. But if the really smart people were running the show, it wouldn’t be too long until they were putting soma in the water. To its vast credit, science fiction seems to know this even when its authors do not. The logic of science fiction narrative is innately moral and conservative. Look at our utopias! They always go hideously wrong. Of course they go hideously wrong, because if they didn’t, there’d be no story.

The most imaginative and dogged utopianist of the previous generation was Iain M. Banks, my favorite living writer until he passed away this year. His Culture is a utopia that works (because it’s wisely and lovingly managed by gods AIs). But every single Culture novel features a clash with another civilization or external baddie. Banks managed the feat of creating a utopia that many of us, including me, would like to try living in, but even he couldn’t get any stories out of it.

heaven utopia is impossible for humans without gods AIs to run it.

The fundamental conservatism of Banks’s science fiction, which ironically contradicts the man’s own views, can be seen in the fact that the Minds of the Culture, being superintelligent, are also good. There are no Lucifers here. Minds may get eccentric or go AWOL, but they never go power-mad and start destroying suns for larfs. Banks’s argument seems to be that post-scarcity, post-disease, post-loneliness, no one is evil because there’s nothing in it for them.

In fact the Culture universe is a vastly expanded and technified version of the solar system depicted in CS Lewis’s classic trilogy, Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra, and That Hideous Strength. The Oyarsa of Mars = the Minds, the Oyarsa of Earth = all those stupid and evil societies the Culture has to battle. Etc., etc. This observation helps us to formulate a law of science fiction narrative: A utopia needs external enemies in order to function narratively. (Yes, that is a word.) Utopias in isolation will always go hideously wrong, à la Huxley.

The question is … drum roll …

Which sort of utopia will we end up living in?

I guess it depends on the solution to the Fermi Paradox. So maybe it’s time to donate to SETI … and vote for politicians who believe that Gross National Happiness is less important than Gross National Aerospace Investment.

***

The problem with utopias is that they are always predicated on the assumption that their goal is a state of eternal bliss, as if simply ‘being’, existing without stress or conflict, guarantees happiness.

Since the human mind is far too complex to tolerate such mind-numbing nothingness, practical utopias will require Soma-like drugs to function at all.

But, bearing in mind I am writing from a purely personal perspective, nothing makes me happier than a sense of accomplishment or achievement (which is odd, since I am inherently lazy), a feeling of triumph if you will. To give you an extreme example, there are no happier men on earth than an anti-tank gun crew who have succeeded in knocking out an enemy tank just as it was about to roll over their position and crush them. True happiness.

I therefore suggest that a true utopia would be under constant threat (albeit faked) and the happiness of every citizen would depend on events being cleverly stage-managed so that each individual saves the day, or the dome, or whatever. Hardly an original idea of course (shades of ‘Total Recall’, etc.) but a mixture of constant threat backed by constant achievement/success/victory would make for eternally happy campers indeed.

Following this line of logic, video games may be the closest thing to a utopia we possess today. But not quite, since one loses more often than not, but at least you get to respawn.

Hmmm… maybe that’s the key to utopia… the ability to respawn…. to live life to the fullest without dire consequences, but without knowing that you will always win, never lose.

In short, a practical utopia, one way or another, will depend on planned ignorance of what is actually going on.

Or to put it another way, life in Heaven is boring, but life in a Heaven locked in eternal combat with Hell is downright exciting. Of course, God has stacked the odds in Heaven’s favour, but the angels don’t need to know that…

No, I think your perspective is widely shared, certainly by me! The idea of a stage-managed utopia fraught with (secretly) unlosable conflicts is really interesting. There’s a story to be written there! But I think people would soon catch on and get bored. If you never lose, you get cocky and decide you’ve got a charmed life, whether it’s true or not.

However, the ability to press restart definitely makes people happy.

So I wonder, is Peter F. Hamilton’s Confederation universe, where people can be “relifed,” a utopia? On the individual scale if not the civilizational? Problem is if that were real, tyrants would abuse the technology to subject people to unending torture.