Part of what makes science fiction so cool is its ability to transport us to new environments, to turn our reality sideways just enough to show us something new about ourselves. Of course, all decent fiction (regardless of genre) does this. But science fiction features a specialized toolkit: world-building, extrapolation, analogy, conceptual breakthrough, thought experiment – these are science fiction’s basic methods. Other genres might occasionally borrow them, but SF has sharpened them to a razor’s edge. So what happens when this set of tools works alongside the themes, styles, and plot structures of noir?

Idea versus Character in Science Fiction and Noir

Science fiction is often called the literature of ideas. Sometimes, this is meant as a compliment: that it pushes boundaries, asks difficult questions, explores possibilities. But sometimes, it is also a criticism: that as a genre, we focus so much on the whiz-bang technological or conceptual conceit that we skimp on the characters.

But this traditional tension gets further exacerbated by the introduction of noir themes. And that’s because noir themes are so character-focused. Technology and imaginative conceits are simply irrelevant to the explorations of morality and personal choice that lie at the heart of noir.

If science fiction authors are trying to strike a workable balance between idea and character, then a successful exploration of noir themes would tip the balance heavily to the character side. Want proof? Think about your favorite hard science fiction authors. Do any of their works explore noir themes?

I love Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy, which explores morality and personal ethics. But its exploration of difficult individual and societal choices never adheres to a noir sensibility. Its focus is too wide, its characters at too distant a remove. This isn’t necessarily bad – it merely points out that the Mars trilogy is far from noir. And this same observation can be made of many “idea-centric” science fiction stories: Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End

, Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy

, Gregory Benford’s Timescape

, Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War

, Iain M. Banks Surface Detail

— the list goes on.

But when we look at more character-oriented science fiction, in particular the “softer” post-New Wave science fiction, we find plenty of noir themes showing up. Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly takes noir themes of morality and crime, and then erases and redraws all boundaries in the best tradition of Jim Thompson. The cyberpunk authors, William Gibson and George Alec Effinger in particular, relied heavily on both noir themes (and plot structures) to gild their stories with a paranoid, claustrophobic edge. More recently, authors like Lauren Beukes (in Zoo City

) and Ken MacLeod (in The Night Sessions

) continue to build on noir themes through their characters.

So on a thematic level, I definitely think that science fiction can explore themes taken from the noir playbook. But it only works if the story focuses enough on the characters, and builds them to the point where they are “lived in” and vivid to the audience. If characterization is kept at a distance, then I expect an attempt at noir themes will end up being neither fish nor fowl.

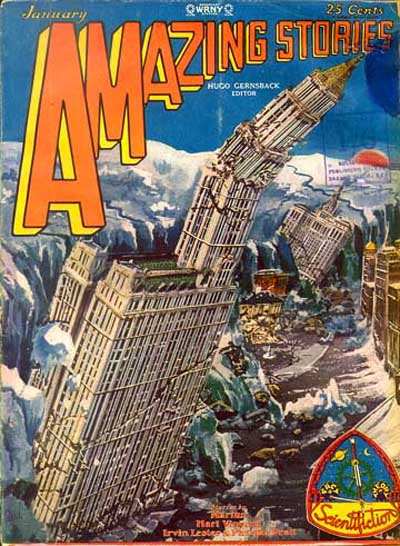

Noir Plot Structures in Science Fiction

Most of the noir-flavored science fiction I’ve read tends to adopt noir plot structures wholesale. That shouldn’t be surprising: both noir and science fiction owe their roots to the pulps of the ’20s and ’30s, so their tropes developed in tandem.

Science fiction tends to eschew the broad sweeping epics characteristic of much fantasy. As a result, its settings and concerns tend to be more locally-focused. Most noir plot structures thematically and structurally require a hyper-localized focus to work, and thus science fiction settings can typically accommodate the plot devices of the classic noir story.

In essence, it is a straightforward continuation of science fiction’s classic methods: Construct an imagined world. Then extrapolate a detective living in that world (Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? or Ken MacLeod’s The Night Sessions

). Play a thought experiment: what new crimes, and punishments, and opportunities will new technology make possible? (William Gibson’s Neuromancer

) How will criminal organizations work in the future? (George Alec Effinger’s When Gravity Fails

).

The same principle extends quite naturally to other media: Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, Joss Whedon’s Firefly

, and Rian Johnson’s Looper

all succeed in employing classic noir plot structures, both by focusing on the characters in question and by creating a vibrant, localized setting.

The Noir Style in Science Fiction

On the face of it, science fiction’s ability to explore noir themes through a focus on character and to employ noir plot structures in an imagined world yields us plenty of noir science fiction. But as I mentioned last week, noir has an emblematic writing style as well, and its use is far rarer in science fiction.

There’s a good reason for that. Science fiction often accomplishes its world-building through the use of neology and through prose description which presents the imagined conceit as a given. In other words, every work of science fiction is founded on an imaginative metaphor. But the noir style, with its appreciation for mimesis, eschews metaphor. Stylistically, it employs simile to lend its imagery emotional flavor from an oblique angle.

This is why even “noir” science fiction like the works of Philip K. Dick, William Gibson, or Ken MacLeod tends not to present as noir. They don’t use the characteristic verbal stylings of the genre, instead choosing to stick to metaphor-laden constructions. I think this is the easier route: it lets the author compartmentalize their world-building efforts, and to deliver it in denser chunks.

But the best authors of noir science fiction can incorporate all three of noir’s constituent components: they can explore noir themes through its plot structures while retaining its stylistic conventions. Consider the opening paragraph of George Alec Effinger’s excellent When Gravity Fails:

Chiriga’s nightclub was right in the middle of the Budayeen, eight blocks from the eastern gate, eight blocks from the cemetery. It was handy to have the graveyard so close-at-hand. The Budayeen was a dangerous place and everyone knew it. That’s why there was a wall around three sides. Travelers were warned away from the Budayeen, but they came anyway. They’d heard about it all their lives, and they’d be damned if they were going home without seeing it for themselves. Most of them came in the eastern gate and started up the Street curiously; they’d begin to get a little edgy after two or three blocks, and they’d find a place to sit and have a drink or eat a pill or two. After that, they’d hurry back the way they’d come and count themselves lucky to get back to the hotel. A few weren’t so lucky, and stayed behind in the cemetery. Like I said, it was a very convenientily situated cemetery, and it saved a lot of time and trouble all around.

– George Alec Effinger, When Gravity Fails

That paragraph could serve as a how-to guide for both science fiction and noir. Stylistically, Effinger’s sentences are declarative and relatively simple, and they instantly bring to mind Jim Thompson’s in construction and tone:

As Roy Dillon stumbled out of the shop his face was a sickish green, and each breath he drew was an incredible agony. A hard blow in the guts can do that to a man, and Dillon had gotten a hard one. Not with a fist, which would have been bad enough, but from the butt-end of a heavy club.

– Jim Thompson, The Grifters

Both Effinger and Thompson use adjectives and adverbs very sparingly, only to highlight some particular emotion or connotation in our minds as we read. But Effinger does far more in his first paragraph, and it is an extremely restrained form of world-building. In six words he accomplishes all of the world-building for which lesser authors would need six sentences.

By casually dropping the word Budayeen – and treating it as if we should understand it – he shows us that the book is presumably set in the Middle East. For most readers, this is already a cognitive estrangement: he takes us out of our Western mileu and puts us into a foreign environment. Then with five (seemingly throwaway words) he further establishes the kind of world the story takes place in: “eat a pill or two”. With those words, Effinger implies that the world is modern enough to have pharmaceutical manufacturing, and because popping pills for one’s comfort and enjoyment is a device traditional of futuristic science fiction, he also suggests that it represents a futuristic world. With a mere six words – and without losing the sparsity characteristic of noir sensibilities – Effinger plunges into both a noir and heavily science fictional environment.

So yeah, I think science fiction can play well with the noir aesthetic. There are, obviously, tensions between the two. But they can be managed, and plenty of excellent authors have done stellar jobs managing them. I think that fantasy, however, has a much harder time doing so. But that’s a topic for next week.

Until then, what are some of your favorite science fiction/noir mash-ups?

Absolutely! I've long been a huge fan of A. Lee Martinez's works, and The Automatic Detective was the first book of his I'd read. After that? I was hooked.

The Automatic Detective, by A. Lee Martinez, is one of my favorite works, ever. It's spare but fun, moves fast, and gives us a very human superdestroyer red robot in the person of Max Megaton.