Some people think of John Shirley as “just” a cyberpunk or horror writer; often lumped in with William Gibson, Bruce Sterling et al., but he’s so much more than that—as is also true of the other writers. (I believe both Gibson and Sterling have acknowledged him as an influence.) Shirley, however, is also a “real” musician (depending on how you feel about punk), who’s had a couple of bands, and who has written something like forty lyrics (according to Wikipedia) to Blue Öyster Cult songs. (I remember one year at Orycon, in Portland—I don’t think it was the year I was Fan Guest of Honour there—when he and his band played for the dance. At least I think it was John; he wore a hoodie and sunglasses.) But that’s not really germane to my subject here. Although his novels City Come A-Walkin’ (1980) and the Eclipse (also called A Song Called Youth) Trilogy, comprising Eclipse (1985), Eclipse Penumbra (1988) and Eclipse Corona (1990) are often called seminal novels in the cyberpunk subgenre of SF, he’s much more versatile than those books alone—if that’s all you know him by—might suggest. He has also done movie and game novelizations and tie ins; notable (from my perspective) are the novelization of the movie Constantine (with Keanu Reeves—notably different from the graphic novel that spawned the movie), and the tie-in novels for both Halo and Bioshock games. (I mention those because I liked those franchises a lot.) He’s also written a Star Trek: Deep Space Nine script.

But here I want to address a couple of books he’s produced in the last two years, specifically in the fantasy and western genres—and those two genres are generally as far apart, one might think, as you can get! The books I speak of (both available in paper and as Kindle books from—and I’m not trying to be a shill for that distributor, but it seems most of what you want is available there—Amazon.com; the books are Doyle After Death and Wyatt in Wichita. (Without weakening my main thrust I might point out that SF authors like Ted Sturgeon also wrote westerns; detective/mystery author John D. MacDonald wrote some terrific SF, so cross-genre writing is not a new thing.)

Good cross-genre writing, however, is another kettle of fish of a different colour! I’m not saying Doyle After Death is a seminal ghost-detective story—in fact, it probably won’t inspire imitators. It might well be (and remain) sui generis, a thing unto itself; who else but John Shirley could imagine a post-death world where the creator of the world’s first and greatest consulting detective would become a detective himself? Or the “town constable,” which is what he became in the after. The after what?

Certainly not the “afterlife,” as people who’ve died don’t care for that phrase—nor do they care to be thought of as dead, since they now lead a life that in some ways has distinct advantages over the “before,” as they now call it. Our protagonist, Nicholas (“Nick”) Fogg (one wonders if he’s related to a certain Phineas Fogg?), who went to sleep in a seedy Las Vegas hotel room after consuming a large amount of booze and a number of pills—and woke up lying near a purple sea (actual wine-coloured purple) in a place he’d never seen before. Nick soon meets the semi-official greeter, Fiona (after whom the currency of this odd place is named), and is escorted to the nearby village of Garden Rest, where a population of the aftered live. He finds out that when you become aftered, you take your clothes with you and whatever was in your pockets (the residents of Garden Rest are perpetually short of tobacco and badger newcomers unmercifully to see if they’ve brought any cigarettes); any before money becomes transformed into Fionas, the local money, as well.

Almost immediately, Nick meets Arthur Conan Doyle (“Wait,” I blurted. “Arthur Conan Doyle? Creator of . . .” I didn’t say the rest, suddenly feeling foolish. Creator of Sherlock Holmes. He glanced at me, pretending embarrassment, but I could see he was pleased, too. “Yes, sir.” He chuckled to himself. “My vanity, of course, wishes you’d mentioned The White Company, something I esteem a bit more, but I’m lucky to be remembered at all and I owe a great deal to the imaginary Mr. Holmes….”) and discovers that, although you can be murdered in the after, many wounds that would be fatal in the before are fairly quickly recovered from in the after. He meets one or two people he knew before, but is told why he doesn’t see, for example, his father. People unconsciously choose where they come—Garden Rest is only one of a number of villages—and some become “forgetters,” people who forget who they were before and end up as disembodied sparks, forever wandering and looking for they know not what; others are Summoned, possibly to an even higher “plane of existence,” as Doyle puts it. (Presumably these are the reasons one doesn’t see many more well-known figures in Garden Rest, though it’s mentioned that Philip José Farmer had been there before, and that Robert A. Heinlein had gone “to the west, in the City of Phantasmic Devices.”

If you know anything about Arthur C. Doyle, you probably know that he was, or became, a spiritualist, a believer in mediums, fairies, spirits and all sorts of things that the hard-headed doctor he used to be probably wouldn’t have acknowledged; a lot of things in the after seem to confirm his later beliefs. Nick Fogg takes all this in; he has an open mind, which is a good thing—because almost daily he sees or encounters something almost unbelievable from our viewpoint. The aftered inhabitants don’t need to eat or drink; they take their nourishment directly from the sun—which is, according to Doyle, an intelligent being rather than a star—although they take pleasure in eating and drinking. No messy bathroom stuff, either—they don’t need to eliminate (and, since they don’t appear to reproduce, they need no condoms or feminine hygiene products). Most people have jobs, since that’s the only way to earn Fionas to pay for their food, drink or lodging; working seems to provide a sense of purpose, to keep one from becoming a forgetter and just wandering off.

Shortly after arrival, Fogg encounters a dead body—or what passes for one here—and discovers that murder can take place; in the company of Doyle (who is the town constable and, fittingly enough, the official detective) he meets Diogenes—we never find out for sure if it’s that Diogenes, though he does wander around with a lantern—and becomes Doyle’s unofficial assistant, since Fogg was a “failed P.I.” in Las Vegas. You might say Fogg becomes Doyle’s Watson. The rest of the book becomes both a travelogue—since Shirley has to describe all sorts of things that are either not seen/done here, or that are different there—and a detective story, not in the least reminiscent of Doyle’s Holmes stories. Well, with one exception: Doyle is always explaining clues to Fogg in a very Holmesian fashion, though he insists that he is merely using the scientific method as explained to him by his own Professor Bell in medical school. Holmes and Watson—oops! I mean Doyle and Fogg—must solve the murder, which is only part of a larger mystery.

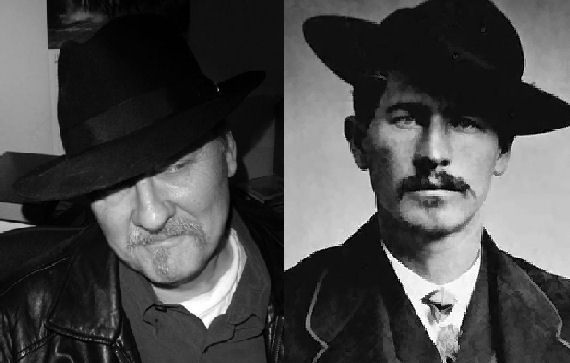

As a fantasy, it’s very much a science-fictional fantasy: where fantastic things happen, they can be explained in a plausible manner—as if one was on a distant planet where physics worked differently, for example—without resorting to actual fairies or witches or disembodied spirits; even the latter have a “scientific” explanation in terms of the after. There are no magic swords, dragons (although there’s an interesting “beast” called The Scargel, whose explanation is a bit dodgy) and the like, but there are talking birds and animals. Again, explainable in terms of the science of the after. As a detective story, it’s not “hard-boiled ‘tec” stuff; indeed, it seems to be more gentle in many ways than even an Ellery Queen or the like. Possibly because so much space has to be used to describe the setting, the “science” of the after, the animals and so on. The book does give you a fair amount—even if you’re not a Doyle enthusiast to begin with—of information about Arthur Conan Doyle and his personality, liaisons and so on. I found it rather enjoyable. I’d call this a good buy—especially if you like fantasy as well as detective stories. I’d like to see another, in fact. (And has anyone else noticed the distinct likeness between some photos of Doyle and Nigel Bruce, the man who played Watson the most often in the movies? See Figure 3.)

That was last year (the book is still available from Amazon.com; I got mine in a Kindle version, though I think it’s available, like our next book, in both paper and electronic versions); the new book is something you won’t see often reviewed in Amazing Stories, as it’s a Western. But not a horse opera or “oater,” as they’re often called. This one is a novelized biography, sort of. Or a biographical novel, more accurately, covering Wyatt Earp (yes, the O.K. Corral guy) when he was in his late 20s, in Wichita, Kansas.

Probably partially because my dad was fond of Louis L’Amour, and partially because I’ll read anything not nailed down (and a number of nailed-down things too!), I’ve read a lot of Westerns. Everything from the aforementioned Louis L’Amour to Max Brand to Willa Cather, Zane Grey, Owen Wister and just about everyone between (including Elmore Leonard and the aforementioned Theodore Sturgeon); so it was no hardship at all for me to jump at the chance to read Shirley’s Wyatt in Wichita.

Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp (March 19, 1848 – January 13, 1929) was a fascinating character; before he settled down in Tombstone Territory (Arizona not becoming a state until, I believe, 1912 or so); according to Wikipedia, he was “an American gambler, Pima County, Arizona Deputy Sheriff, and Deputy Town Marshal in Tombstone, Arizona, and took part in the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral…. To Earp’s displeasure, the 30-second gunfight defined the rest of his life. He is often regarded as the central figure in the shootout in Tombstone, although his brother Virgil was Tombstone City Marshal and Deputy U.S. Marshal that day, and had far more experience as a sheriff, constable, marshal and in combat.” (Emphases mine.)

Actors who’ve played him in movies and TV include Randolph Scott, Joel McCrea, James Stewart, James Garner, Guy Madison, Henry Fonda, Burt Lancaster, Kevin Costner; and Kurt Russell, Hugh O’Brien and Val Kilmer. The closest film to this book—portraying Earp in the same period—is McCrea’s Wichita (1955), although many events in the film, according to some sources I read, are extremely fictionalized. (Gee, what a surprise; a fictionalized movie.) I’m pretty sure I’ve seen most if not all of the above movies, though I don’t remember the McCrea or the Madison.

The book opens in 1870 (Earp being 22 at the time) in Lamar, Missouri. Earp loses his wife and newborn daughter to typhoid fever. He leaves Missouri for Arkansas and tries to drown his sorrows in whiskey, forgetting his father’s admonitions against drunkenness. He becomes involved with low-lifes, getting himself arrested for bilking a man of a horse; his father has to bail him out and he leaves Arkansas for Illinois. In Illinois he falls into lower company, becoming a common-law husband for a prostitute, Sarah (as well as being her pimp), and eventually leaving her; two years later we find him skinning buffalo near Ellsworth, Kansas with Bat Masterson. They’re both tired of the business, however, and Wyatt is thinking of becoming a teamster; selling his oxen and buying horses to carry freight instead of buffalo skins.

He’s also taken up an occasional liaison with “Mattie” Blaylock, a saloon girl of easy virtue (marrying a whore was somewhat frequent in those days and places; it was called “white-washing a soiled dove.”), though he remembers the troubles he had with Sarah. He becomes involved in a shooting dispute between a man he once helped, Ben Thompson, against heavy odds (four against one) and a deputy named Murco; Thompson’s brother drunkenly and accidentally shoots the sheriff, and Wyatt is deputized to arrest Ben after Ben helps his brother escape. Heart in mouth and hands raised, Wyatt faces a heavily-armed Thompson down and talks him into surrendering. Murco and a cattleman, “Shanghai” Pierce, plan to storm the jail, drag Thompson out and lynch him; Wyatt foils that plan and makes a lifelong enemy out of Pierce, who’s not playing with a full deck anyway, but who has much money and a lot of sycophants in Texas and Kansas anyway. From there, the Earp/Pierce situation escalates. You also meet a young man named Henry McCarty; Western readers will recognize the name immediately.

This book is written just as well as any Zane Grey or Louis L’Amour I’ve read; one gains a lot of sympathy for Earp who, as the reader will be able to tell, is just trying to make his way in a world that is often violent and unforgiving. Shirley uses fewer adjectives than Grey does; and he doesn’t wax lyrical as often as L’Amour used to; the book is not only competent, it’s exciting—one can’t wait to see what happens to Earp next—and from time to time it’s easy to think of this as a movie in waiting. (I’m kinda visual myself, and usually see a novel—even a biographical one—as a movie in my head.) If you like well-written Westerns, or just well-written novels, especially ones that give you a sense of the Old West, then this will be a book for you. Again, I got mine from Amazon.com as a Kindle book, but I think it’s available in paper as well. If I have anything at all negative to say about these books, it is that the covers are rather nondescript; I believe that a good cover can help attract readers and these don’t (again, my opinion alone) serve that function.

Has anyone else noticed the odd resemblance between John Shirley (left) and Wyatt Earp (right) in these pictures? And I don’t just mean the hats!

If you can—and feel like it, please comment on this week’s column/blog entry. If you haven’t already registered—it’s free, and just takes a moment—go ahead and register/comment here; or comment on my Facebook page, or in the several Facebook groups where I publish a link to this column. I might not agree with your comments, but they’re all welcome, and don’t feel you have to agree with me to post a comment; my opinion is, as always, my own, and doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of Amazing Stories or its owners, editors, publishers or other bloggers. See you next week!