I seem to be unable to do single columns about stuff I’m passionate about. Heinlein is no exception. Robert A. Heinlein, who was characterized as the “Dean of Science Fiction,” though he was not necessarily the oldest or the best writer of SF during his lifetime, began his writing career before he went back into the Navy during World War II. He began writing for John W. Campbell, the editor at Astounding (which changed its name to Analog in the 1960s), and quickly became one of the most popular writers of SF in the US. From his first-published story, “Lifeline,” to the last novel published in his lifetime (1907-1988), To Sail Beyond the Sunset, Heinlein had, perhaps, a disproportionate effect upon the science fiction field, and—going by myself—upon the young SF reader (usually, but not always, male). (When I was growing up, the usual acknowledgement of influential authors was The Big Three (plus one), or “ABC plus one”—Asimov, Bradbury, Clarke, plus Heinlein. Each writer in that group brought strengths (and weaknesses) to the field; Asimov tried to include the social sciences—in a very SFnal way—with his robots and his “psychohistory”; Bradbury, though he was more of a fantasist (see his “Mars” stories) than an SF writer, brought a certain lyricism to SF; Clarke was, perhaps the most “Hard SF” of the three. But Heinlein, with his “future history” and his juveniles, just might have influenced more of SF than the other three.

For the younger or less well-read fan who isn’t familiar with the named writers, I suggest you check out Asimov’s Caves of Steel (robots) or Foundation (psychohistory); Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles or Fahrenheit 451; or Clarke’s Childhood’s End or The City and the Stars to begin with, and expand from there. (For those who would wish to castigate me for not including Simak, or Sturgeon or Clement or any of a couple of dozen other significant authors of the ‘40s, ‘50s and ‘60s, those people will be discussed, but they are not the “leaders of the pack” in the way the four names I mentioned were.)

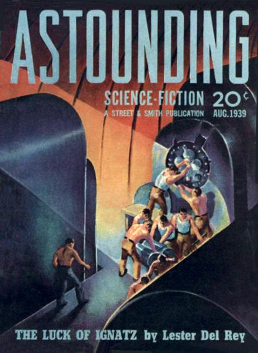

Back to RAH: from 1939 to 1942 he published a number of short stories, but until the war was over and he was back in civvies (i.e., out of uniform) his output was nil. He picked up his career writing what were then called “Juveniles,” where the intended audience was under 18 or so (we now call them “YA,” or Young Adult), and usually the protagonist was too. His first published short story was in the John W. Campbell-edited Astounding. It doesn’t (Figure 1) appear to have been the “cover story,” though from what I can tell, the Finlay cover might not fit any of the interior stories—part one of an L. Ron Hubbard serial under a pseudonym, a Murray Leinster story—“The Luck of Ignatz” (which was, in fact, the main story in last week’s Winston compilation by Lester del Rey) and stories by L. Sprague de Camp, P. Schuyler Miller, Nelson Bond and Ray Cummings. Certainly there was no indication that this was to be the foundation for a career less ordinary than most.

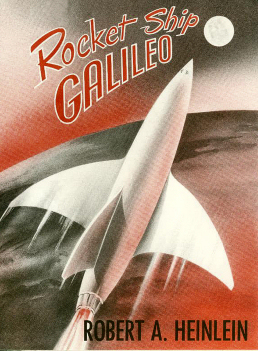

After the war, Heinlein started writing YA, or “Juvenile” fiction—although not exclusively—his first published novel, in fact, was a YA book: Rocket Ship Galileo, published by Scribner’s. (All of his first dozen or so YA books were published by Scribner’s until they refused to publish Starship Troopers (1959), feeling that it would not be appropriate for a teenaged audience. At that point he left them and his next book was, I believe, from Putnam (Stranger in a Strange Land) 1961). He is reported to have said he was tired of being known as just an author of YA books.

Instead of one teenage protagonist, Galileo had three; the story involved a trip to the moon and the establishment of a base there by the same teenagers. There was also an improbable sub-plot involving Nazis on the moon but (Iron Sky, anyone?) nobody takes that sort of thing seriously, right?

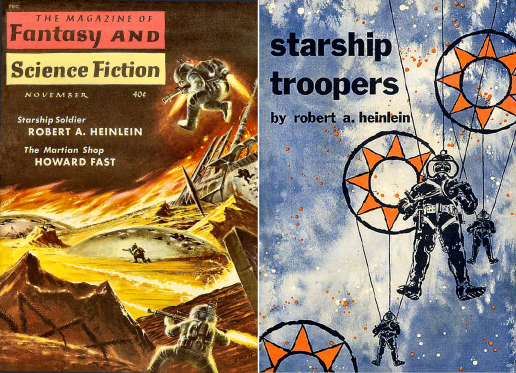

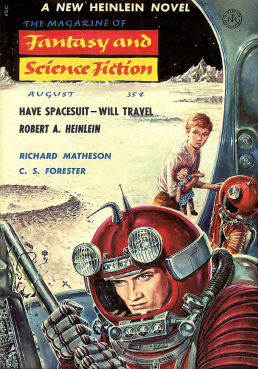

After Rocket Ship Galileo, he published the YA books Space Cadet (1948), Red Planet (1949), Farmer in the Sky (1950), Between Planets (1951), The Rolling Stones (1952) (also called Space Family Stone), Starman Jones (1953), The Star Beast (1954), Tunnel in the Sky (1955), Time for the Stars (1956), Citizen of the Galaxy (1957) and Have Space Suit—Will Travel (1958). As mentioned before, Scribner’s refused to publish Starship Troopers (1959), which Heinlein intended as a YA book. (Although many of the themes would be considered adult today, and quite militaristic, I believe Heinlein was attempting to be didactic—exploring, if not exactly espousing, ideas on citizenship, duties to one’s family and country and so on.) Starship Troopers, as well as Have Spacesuit—Will Travel, first appeared in F&SF (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction) as serials—both magazine covers are by Ed Emshwiller, though I don’t know who did the Putnam hardcover image.

To my mind, the significant Scribner’s YA books—the ones that really stand the test of time (and age; I’m sure not a young adult any more!) are as follows: Red Planet, The Rolling Stones, Tunnel in the Sky, Citizen of the Galaxy and Have Spacesuit—Will Travel. The others are good (in my opinion) but not as good as these. (People will say, “What? You left out The Star Beast? What about Lummox?” or similar about the others. Hey, what can I say? It’s a personal column about personal opinion. I think the young SF fan would benefit from reading ALL the Heinlein YAs; I just think these are the most significant.) Red Planet introduces Martians similar to the nymphs in Stranger in a Strange Land; The Rolling Stones introduces Hazel Stone, who later becomes a significant part of The Moon is a Harsh Mistress and Time Enough For Love, and so on. Although the YA books don’t really fit into his “Future History” (which, if you don’t know, was introduced in Astounding in about 1941)—a chart, which became part of the endpapers of many Heinlein hardcovers—that shows the so-called history of the human species from the 20th century to the 23rd century, and how many of his novels and stories fit into it.

A significant number of his stories and novels did so; a number, including many of the YA books, did not; for example, Have Spacesuit—Will Travel. (For those of you who don’t know, the title was an attempt to cash in on the popularity of the then-current Western TV series Have Gun, Will Travel, starring Richard Boone as Paladin, gunfighter for hire. The book had—as far as I can remember—no resemblance whatsoever to the TV series, except for the names. (An interesting bit of trivia; Boone’s gravelly voice later became the voice of Smaug, Tolkien’s dragon in The Hobbit in the Rankin-Bass TV adaptation. To me, that voice characterization is probably the best thing about the move. The worst? Glenn Yarborough’s singing. But maybe that’s just me.) Have Spacesuit—Will Travel tells the story of Kip Russell, who tries to win a trip to the moon, but instead wins a used spacesuit—missing most of the important bits—in a slogan-writing contest—and restores it. (I can sympathize: I, personally, have restored a number of things from rusty and missing parts to near factory-new condition. It’s fun!)

Kip accidentally takes a ride on a spaceship and meets The Mother Thing, an oddly maternal alien being and Peewee Reisfield, a young girl—as well as some less desirable aliens. A couple of things I found really fun about this book were that one, his father placed an emphasis on being self-reliant and how to get what you want by playing the system; and two, his father’s system of paying income tax, which was to have a big basket by the front door into which he dropped his loose bills and change—the “household accounts.” Every so often, he’d box the whole thing up and send it to the IRS. When the IRS remonstrated with him, telling him the government required him to keep accurate records, he replied “The government can’t even require me to read and write”! I wish I had the… er, guts to try that. But I don’t think I’d enjoy prison.

Another thing I’d like to point out—which, if you haven’t read these books you might not notice—is that Emshwiller painted both F&SF covers after actually reading the stories: in Starship Soldier (the F&SF title for what was later published as Starship Troopers), the soldiers are wearing powered armor (unlike in the movies) as well as the “bugs” are probably arachnids, as described in the book (again, unlike the movie). Sometimes, there’s little enough in the cover that makes it appear the artist has read the book. Emsh wasn’t like that—compare his cover to the hardcover art. Are those powered suits? Can’t tell. And on the Have Spacesuit cover, Kip’s suit has the two antennae described in the book: one omnidirectional, and one directional “horn” antenna. Peewee has her doll, Madame Pompadour. (The only thing “wrong” with these covers, IMHO, is that he didn’t try to hide the “EMSH” signature. I feel vaguely cheated.) As usual, I won’t tell you enough about the books to spoil them if you haven’t read them.

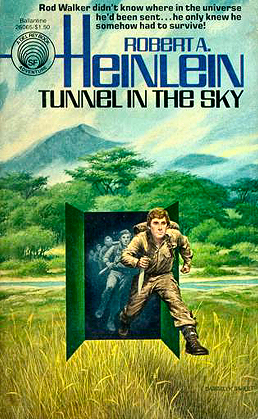

Anyway, Tunnel in the Sky introduces Rod Walker, who is taking a course in “Advanced Survival,” which is required for students who want to be explorers, planetologists and the like; without the Solo Survival Exam—which isn’t required just to graduate high school—they can’t join any of those specialties. The Earth is using something very similar to wormhole technology to send colonists to Earthlike planets all over the galaxy; and explorers, planetologists, scouts and colonial administrators of all kinds are required; all of those people have graduated after taking the Solo Survival exam, which is basically all these kids are schooled in survival and then dumped—as a class (all those who wish to take the exam)—on an alien planet (or a wild part of Earth, maybe) alone and have to survive until pickup, which can be from 48 hours to ten days later. To fail this test might mean the student’s death. To fail to take the test means the student hasn’t proven he or she is responsible enough—or enough of a survivor—to be depended on by others. Rod and his classmates—twenty out of the fifty who took the course—are warned that there is no law and no order where they’re going, and hazards can include the two-legged kind. They’re dumped in wild country with only whatever they’ve brought with them and warned to “watch out for stobor.” (Figure 5 shows that Darrell Sweet had read the book and found that Rod had brought just a pair of knives, no guns, to help him “think like prey rather than like a predator” for better survival.)

Although Rod and his classmates—the ones who survived the initial day—wait and wait for the recall signal, they eventually figure out that something’s gone wrong and they might be there for the rest of their lives. How they set about making this part of the unknown planet their home is a major portion of the book. One feature of many of Heinlein’s YA books is the “old man” who lectures the protagonist and sets him straight on many of the wrong ideas he’s been carrying around with him; Tunnel is no exception. Like Colonel Dubois in Starship Troopers, Deacon Matson in Tunnel is the ex-military (or ex-exploratory in this case) schooteacher who helps the young protagonist find out things he needs to know, while exposing his “fuzzy thinking”!)

One feature of this book, in common with most Heinlein books, is the “competent female,” in this case both Caroline Mshiyeni, an African girl and Rod’s sister, Helen—who is a “Captain in the Amazons.” It may be fair to say that Heinlein—in concert with my having a strong, self-willed mother—helped shape my opinion of, and interaction with, women. Because Heinlein usually contrasted the competent female with one “traditional” (read 1950s airhead) type in the same book, I became familiar with both types of women to an extent, unconsciously comparing the women I knew with both types and expecting women to be at least as competent and self-confident as the men I knew. It took me many years, as I grew up, to realize that there were as many degrees in women as there are in men.

Anyway.

Starship Troopers hardly needs introduction; while most fans have seen at least one of the movies, I’m sure a number were led by the movies to search out and read the book. And I wonder how many were disturbed to realize that the movie is an extreme and one-sided version of the book; its director, Paul Verhoeven has said that he’s never read the book himself. In the next installment of this column, I will talk about the differences between Verhoeven’s version and Heinlein’s own version.

To comment on this week’s entry, you can either register here (if you haven’t already—it’s free, and only takes a moment) or comment on my Facebook page—or in the several Facebook fan groups where I publish links to these columns. Your comments, whether positive or not, are always welcome! My opinion is, as always, my own, and doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of Amazing Stories or its owners, and there’s no downside to disagreeing with what I say. See you in next week’s blog entry!

Steve has been an active fan since the 1970s, when he founded the Palouse Empire Science Fiction Association and the more-or-less late MosCon in Pullman, WA and Moscow, ID, though he started reading SF/F in the early-to-mid 1950s, when he was just a sprat. He moved to Canada in 1985 and quickly became involved with Canadian cons, including ConText (’89 and ’81) and VCON. He’s published a couple of books and a number of short stories, and has collaborated with his two-time Aurora-winning wife Lynne Taylor Fahnestalk on a number of art projects. As of this writing he’s the proofreader for R. Graeme Cameron’s Polar Borealis and Polar Starlight publications. He’s been writing for Amazing Stories off and on since the early 1980s. His column can be found on Amazing Stories most Fridays.

Enjoyed this post a lot, and since I never read a number of these despite being a Heinlein fan for 50 years, it inspires me to try them. I would point out, though, that “Have X, will travel” was a common American classified ad formula for plumbers and skilled tool-workers of all kinds; that’s where the TV show title came from and the book’s title may simply have used the same trope. The show did come out one year before the book, and was immediately popular; still, publishing schedules were usually very slow, and copying the title seems rather unHeinleinesque. If you can cite authority, of course, that’s something else again, but I wouldn’t just assume he was trying to cash in on the TV show.

Very nice overview of the stories and the artwork that helped sell them. Thanks so much for the information and insights.

Excellent, so far. My personal favorites are Starman Jones, Space Cadet, and Rocket Ship Galileo (the first one I read).