I cry when you come to the door. It has been almost three weeks since you were hit walking home. And now, here you are, in t-shirt and khaki slacks, with the hesitant half-grin you wear most of the time. Your skin is the color of coffee in the afternoon light. On the porch, the sunlight, as it makes its way down through the oak leaves, is almost as hesitant as your grin.

“Hey, I’m sorry . . .” You look confused when you see my tears, and I try pushing them off my cheeks, hiding them behind the hands I brush at my eyes.

How much of you is left?

“What do you remember?” I manage after a deep breath. I tense every time a car goes down the street behind you.

You bite your thin lip. Your parents are wealthy, which is why you live in the mansion on the river. Back-ups for you probably happen, what? At least twice a year? People normally don’t talk about it, when or how often. It’s considered awkward, rude to ask.

I try to remember if you had missed school any of the days in the weeks before the accident, but I can’t. Everything from those days is a blur: our time together, what happened, your sudden absence.

“Nothing about that,” you finally say. “Nothing about dying.”

You said it first: dying. Something inside me relaxes at that, dials back a fraction of whatever unit is used to measure pure emotion. Dying. Dead. You were dead. You had been dead. That night, when you walked away from this porch, late, not back to your house, but down the street to the park. And, the car had been traveling too fast, had hopped the curb at the curve beside the river. Had lost control. Had run you down.

Had killed you.

My parents had said something casually racist about black kids and tragedies usually involving guns. Like there was some connection. Like you had died the wrong way. I had put my fist through a wall.

They didn’t know about us.

I didn’t see the accident. I had turned away too early, gone inside, and in the morning, when I heard, it was like the news was a knife carving my stomach open, and all I could think was, did I hear it happen? The music in my bedroom, my eyes closed, trying to drink in everything from before you walked away, everything you had told me as we sat together on the porch, the feeling of your hand in mine.

And now here you are. Whole and unbroken. Not a scratch.

“Do you remember?” I whisper again.

I should ask you to sit down, take one of the plastic Adirondacks on the porch or come inside. But I don’t. I keep you standing there, stiff and brand new, in the doorway.

“I remember waking up,” you say. “At the clinic.”

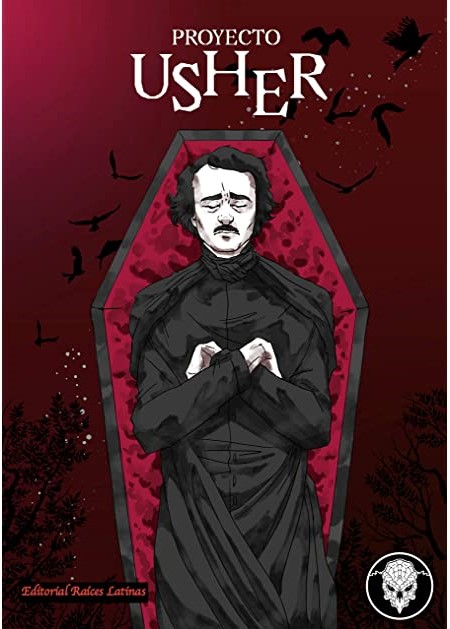

We had been to the clinic on a field trip in junior high. It felt like a cross between a hospital and a funeral home. The regeneration units, sitting in pairs in every room like silver coffins, like something from a cheap sci-fi movie, human-sized escape pods, except they were for escaping death. Cells got knitted together, bodies reformed, memories downloaded, damage undone.

I wait.

I had already waited. Almost three weeks. From the time you died, that was how long you had to stew in that weird marinate, that nutrient bath, before you came back. I went to school every day, trying not to imagine you waiting beside my locker, not to notice your empty seat in every third and fifth period, the place beside the tree where you waited to walk me home. Almost three weeks to spend not imagining you sleeping, half-formed, under glass.

“I found a note,” you say slowly. Trying to keep the confusion out of your voice. “From you. A few, actually.”

Do you remember, I want to ask a third time. But I don’t.

I hear my answer in your confusion.

People don’t have to die anymore, not for good. The person at the clinic explained that to us on the field trip. Yet, pieces could still get lost. Pieces could die. It depended on how often back-ups took place.

“What was the date of your last back-up?” I ask.

Too loudly. Too urgently.

But that is the question, the only real question, the question that will tell me exactly how much of you I lost–or rather, how much of you I suddenly never had at all.

Your parents are wealthy, after all. The date might be recent. Things happen so quickly at this age, my parents say, as though it is a warning or maybe a regret. Things started so quickly between us, and they could have gone in so many different directions. Love broke along a stuttering path like lightning. Blink your eyes, and you miss it. Blink your eyes, and it never happened at all, it broke in another direction, it followed another path.

But your parents have money. Your last back-up might have been after it started between us, after that day walking home in the rain, that night on my porch, the notes.

My parents’ insurance plan allows one back-up every three years. It’s expensive and time consuming. An image of your entire neural network, your brain on a cellular level with every braiding connection mapped and mirrored, built up over a day of sitting on a magnetic imaging table. Boring and tedious. But the back-ups meant when a body came out of the pod, it had a personality and memories waiting for it. For those who weren’t rich, it meant rolling the clock back a year or two. If I died now, my parents would get a version of me that still loved horses, drew for hours every day, and wanted to be an engineer.

What version of you are you? Pre-us or post-us?

You say a date.

It is a month too early.

My version of you, the version of you that knew about us, is gone.

“Look,” you start again, your face a pained study of courtesy, of a strained politeness that is the worst thing possible in that moment. “Look, I’m sorry. I read them. They were addressed to me, so . . .”

Not you. A later version of you.

How can you re-create the precise order of events, that one particular glance or laugh, the long conversation under the same conjunction of moonlight, lamplight, streetlight? The first touch? The fact is that nothing is destined. Change a single coordinate, a single branching link in that chain, and the outcome is completely, utterly different. A different branching, and nothing is created, no one falls in love.

You say my name, almost helplessly. “I’m not like that. I don’t . . .”

Not yet, I want to say. You don’t yet. Not now.

And not with me.

You hand me the letters, crisp and clean in your long fingers. “I’m sorry.”

The day after a back-up, everyone has a bit of a headache and a lingering sense of déjà vu. The sense of being about to remember something forgotten for only a moment. You woke up with a set of memories in which I was only what I had ever been to you, nothing more. In which we hadn’t come out together. For you, the branch of events that made us is gone.

That version of you is dead.

I go inside and you walk back across the street, and I try not to hear the sound of wheels erasing, erasing, erasing you.

END