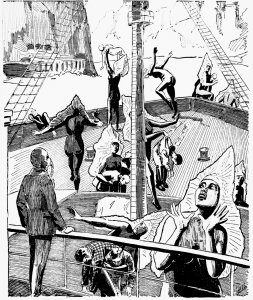

A woman stands inside a glass, egg-shaped container that is wired to an elaborate electronic device. The lower half of her body is translucent, as though she is dematerialising. The man operating the machine looks on with eagerness; a second man, bound to the wall, reacts to the scene in horror. The woman herself looks upwards with a beatific smile on her face, almost as though she is ascending to heaven.

Elsewhere, two red-skinned women – one young, one elderly – lie upon separate beds. A pair of men watch over them: one is an unremarkable Caucasian, while the other is a bulbous-headed individual whose skin is even redder than that of the two women. The two men appear to be carrying out some sort of medical procedure upon the younger woman, although the exact purpose of their weird apparatuses is not entirely clear.

It was July 1927, and readers of Amazing Stories were given a double treat: as well as the regular monthly issue, Experimenter Publishing had put out the Amazing Stories Annual. No further annuals would follow, but the monthly series would be joined by Amazing Stories Quarterly the following year.

In his somewhat meandering editorial to the July issue, Hugo Gernsback starts off discussing scientific errors. He describes how scientist Simon Newcomb deduced that aeroplanes were a physical impossibility, and then relates how his own magazine Modern Electronics received articles from readers trying to demonstrate that television could never exist. From here, Gernsback moves on to current developments in the television field, before musing about infra-red rays and high-frequency sounds that cannot be detected by human senses.

While the previous issue of Amazing printed the winners of the recent story contest, this instalment publishes the runners-up. And so, readers in July 1927 would have been greeted with four more stories inspired by the December 1926 cover illustration…

“The Ether Ship of Oltor” by S. Maxwell Coder

In 2036, a passing star narrowly avoids colliding with the solar system. Although Earth survives this encounter, it ends up with a new neighbour: the planet Neone, a former a satellite of the passing star that has been sucked into the orbit of Earth’s sun.

In 2036, a passing star narrowly avoids colliding with the solar system. Although Earth survives this encounter, it ends up with a new neighbour: the planet Neone, a former a satellite of the passing star that has been sucked into the orbit of Earth’s sun.

One night, while gazing up at the new planet in the sky, the crew of an ocean liner see a spherical vessel descending from the sky. The craft pulls their ship into the air using some sort of magnetism; through telepathy, a pilot orders them to hand over all gold on board.

The shipmen do so, and are rewarded with a tour of the spherical craft. It turns out that the pilots are a humanoid species from Neone, equipped with membranous webs across their heads and arms; these act as extensions of their powerful brains, granting them telepathic abilities. They were in urgent need of gold, as their craft uses it as fuel.

The alien pilot Oltor turns out to be a friendly sort, and the Earthmen take him on a trip to a terrestrial city. He then returns the favour by giving them a voyage to his homeworld, only for them all to become embroiled in a war between Oltor’s red-skinned people and a brown-skinned race from elsewhere on the planet. The latter side initially has the upper hand, thanks to an advanced weapon (“some kind of invisible radiation which causes intermolecular strains of such a magnitude that cohesion is overcome and solid matter disintegrates”) but the Earth crew’s resident scientist, Professor Staunton, helps Oltor’s people to victory. With the war over, the two sides put aside their differences and world peace is achieved on Neone.

A relatively slight narrative, which is used – in true Gernsbackian fashion – primarily as a vehicle to discuss various high-tech gadgets and scientific concepts.

“The Voice from the Inner World” by A. Hyatt Verrill

When a ship vanishes at sea, the public becomes concerned that it had been hit by a meteor, as a light in the sky had been spotted at around the same time. Another ship goes off to find some trace of the missing vessel, only to vanish in turn. Then, when it appears that the mystery will never be solved, a radio operator receives a message that tells the whole story…

When a ship vanishes at sea, the public becomes concerned that it had been hit by a meteor, as a light in the sky had been spotted at around the same time. Another ship goes off to find some trace of the missing vessel, only to vanish in turn. Then, when it appears that the mystery will never be solved, a radio operator receives a message that tells the whole story…

This account follows one of the people on board the ship. After the apparent meteor turns up, the ship is hit by an outbreak of poisonous gas; the narrator is the only one to reach a gas mask in time and avoid being knocked unconscious. Next, the vessel floats into the sky towards the meteor – which is in fact a mechanical airship.

The flying vessel takes the ship to a weird city in a mountainous region. Here, the protagonist encounters the race of beings familiar from the other contest stories: red-skinned humanoids with large frills across their heads. However, Verrill adds his own twists by making this a race of thirty-foot women (“That there should be a cannibalistic race of females somewhere in our world is, after all, not impossible not improbably”, says the editorial introduction). The giant Amazons immediately set about eating the unconscious crew of the ship. Fortunately, these beings react with fear to the sight of the gas-masked protagonist, who manages to escape.

The story delves into some of the barbaric practices of this strange society. For one, it turns out that the species does have males, who are much smaller than the females. But the race allows only enough men to survive as is necessary for reproduction, with surplus specimens being euthanised. The story also reveals that stealing ships is a regular practice for this people, with the USS Cyclops (a real-life craft that vanished near the Bermuda Triangle) being one of their earlier targets.

Can the ship-stealing Amazons’ reign of terror be ended? Yes, as it happens: one of the protagonist’s discoveries is that the giants launch their flying machine using a volcanic crater; should that crater be destroyed, the giants will no longer prey on shipping. And so the main character delivers sends this bizarre account from the stolen ship’s wireless room, before committing suicide to evade capture.

Verrill’s work had already run in Amazing, and it is hard to miss that he was recycling elements from past stories with this contest entry: he had tackled lost races in “Beyond the Pole” and “Through the Crater’s Rim”, and his “The Plague of the Living Dead” also has a resolution involving a vessel launched from a volcano. Meanwhile, the very end of the story – with a radio broadcast being cut short by the speaker’s death – seems to have been lifted from H. G. Wells’ The First Men in the Moon.

“The Lost Continent” by Cecil B. White

Unlike most of the contest entraies printed in Amazing, this story is more interested in the spherical craft than in the frilled humanoids.

Unlike most of the contest entraies printed in Amazing, this story is more interested in the spherical craft than in the frilled humanoids.

Dr. Joseph Lamont demonstrates a pair of inventions. One is a small, round machine capable of hovering in the air in defiance of gravity. The other is a device that creates fields of distortion in the fourth dimension, allowing objects to be sent back in time. “This is H. G. Wells ‘Time Machine’ come to life and no mistake” says Harvey, one of the two observers.

Lamont then assigns Harvey and the narrator the task of constructing a large-scale version of the flying machine, one big enough to be manned. Once this is built, Lamont sets about using it in a scheme to prove the existence of Atlantis, a pet subject of his late brother.

The doctor takes not only his flying sphere but also an ocean liner (which counts the narrator amongst its passengers) back in time with him. The crews of the two vessels witness Atlantis and its inhabitants, who turn out to be the now-familiar red-skinned humanoids; this story’s variation on the theme establishes that their white structures are items of clothing, rather than bodily appendages, and may have inspired the headdresses worn by certain Native American tribes. The Atlanteans are advanced in terms of art, so much so that they have already composed a piece of music strikingly similar to Massenet’s “Elegy”.

Due to a last-minute error, Lamont and his sphere are stuck in the past while the ocean liner arrives back in the present. The story ends with the narrator arranging a rescue mission, using the plans left behind by the doctor to assemble a new time machine.

“The Gravitomobile” by D. B. McRae

The final runner-up is again focused more on the machine than the creatures. University dropout Albert Fisher learns that one of his old classmates, mathematical prodigy Harry Teasdale, is now operating a mine in Mexico. Intrigued, Fisher goes to visit his friend.

The final runner-up is again focused more on the machine than the creatures. University dropout Albert Fisher learns that one of his old classmates, mathematical prodigy Harry Teasdale, is now operating a mine in Mexico. Intrigued, Fisher goes to visit his friend.

It turns out that Teasdale picked his new location because the area’s earth contains a matter with high radium content, something beneficial to his research. While there, he developed a device capable of levitating; he did so after deducing that gravitation is “a vibration in the ether having an extremely short wave length, far shorter than any other radiation known”.

Teasdale follows this successful experiment by building a much larger version of the levitating machine, one capable of flying to Mars. When it is complete, Teasdale and Fisher head off to the red planet; equipped for any eventuality, they even take an ocean steamship with them.

Once they reach Mars, the flying machine suffers a sudden fault and begins plummeting down a ravine. The travellers catch sight of the planet’s inhabitants (who are, of course, red-skinned humanoids with wing-like growths) before crashing… at which point Fisher awakes to find himself being chided by his college professor for falling asleep during a class. The story’s editorial introduction rather charitably calls this an “O. Henry ending”.

“The Plattner Story” by H. G. Wells

This 1896 story begins with the narrator introducing us to Gottfried Plattner, a schoolteacher who – at a certain point in his life – had his entire body reversed. After that point his heart was found in the right of his chest, he became left-handed rather than right-handed, a few aspects of his face were inverted and so forth. The key event occurred when, conducting a chemistry experiment at his school, Plattner combined a green powder of uncertain origin with a few other substances and ignited the resultant mixture. The mixture exploded, and Plattner vanished in full view of his class.

This 1896 story begins with the narrator introducing us to Gottfried Plattner, a schoolteacher who – at a certain point in his life – had his entire body reversed. After that point his heart was found in the right of his chest, he became left-handed rather than right-handed, a few aspects of his face were inverted and so forth. The key event occurred when, conducting a chemistry experiment at his school, Plattner combined a green powder of uncertain origin with a few other substances and ignited the resultant mixture. The mixture exploded, and Plattner vanished in full view of his class.

Several days later, after numerous people in the neighbourhood had strange dreams about him, Plattner returned. He provided a full account of his experiences…

After the explosion, he remains in the school laboratory and sees the boys, but finds that they are completely intangible, with one walking right through him. The outside world now has an immensely dark sky, the land bathed in weird greens and reds.

Inhabiting this unearthly milieu are floating creatures that resemble human-headed tadpoles. They have expressions of intense emotion; some show anger or happiness, but most reflect anguish. One bears a resemblance to the school’s principal, Lidgett. These beings emanate from a mausoleum-like building which contains a burning green fire and letters in an alphabet that Plattner does not recognise. He hears heavy footsteps and runs out to investigate, but never manages to catch up with the source of the sound.

He sees more of the “watchers”; some have the faces of people he once knew but who have since died, including his parents. He witnesses a man dying in a house near the school, and a cloud of Watchers hover over this individual. Then, Plattner realises that he is being pursued by a shadowy black figure. He runs, takes a tumble, and winds up back in his own dimension. (His body has been reversed, although by this point, that is the least bizarre aspect of his ordeal.)

In true Wellsian fashion, “The Plattner Story” starts out as a whimsical yarn about a mildly wuirky concept but goes on to develop into something genuinely disturbing. Taking the scientific concept of a fourth dimension as a starting point, Wells tells a ghost story that moves well beyond genre conventions and offers a more individual vision of the world beyond, just as H. P. Lovecraft would later do.

“Von Kempelen and His Discovery” by Edgar Allan Poe

Having already reprinted Edgar Allan Poe’s 1844 balloon hoax, Amazing again showcases Poe in prankster mode with this piece. “Von Kempelen and His Discovery” was originally published in an 1849 edition of The Flag of Our Union, where it was presented as a factual article – despite being complete fiction.

Having already reprinted Edgar Allan Poe’s 1844 balloon hoax, Amazing again showcases Poe in prankster mode with this piece. “Von Kempelen and His Discovery” was originally published in an 1849 edition of The Flag of Our Union, where it was presented as a factual article – despite being complete fiction.

The story takes place in the aftermath of a discovery by Von Kempelen, hailed by the public as unanticipated in the annals of science. Before clarifying exactly what this discovery is, the narrator argues that, in fact, a similar discovery had already been made by a chemist named Sir Humphrey Davy. The narrator also dismisses the claim made by one Mr. Kissam of having also made the discovery before Von Kempelen; indeed, he comments that the newspaper report on Kissam’s claim “has an amazingly moon-hoaxy-air” (a nod to the Moon Hoax of 1835, which had also found its way into Amazing).

After briefly touching upon the research of Humphrey Davy, the narrator then goes on to offer an anecdote about Von Kempelen (having been a prior acquaintance of the man) involving the scientist’s arrest on suspicion of forgery. The police found quantities of a metal in his possession which they took to be brass, but was in fact pure gold. This, then, was Von Kempelen’s discovery: a method of turning lead into gold. The story ends with some sober-minded ruminations about the effect of this discovery upon the economy.

“Radio Mates” by Benjamin Witwer

This story is framed as a letter sent by the main character Bromley Cranston to his cousin. The tale kicks off with Cranston on an expedition to Afghanistan in search of radium; while there, he hears that his lover Venice Potter has spurned him for rival Howard Marsden. Returning home, Bromley spends the following years brooding over his loss.

This story is framed as a letter sent by the main character Bromley Cranston to his cousin. The tale kicks off with Cranston on an expedition to Afghanistan in search of radium; while there, he hears that his lover Venice Potter has spurned him for rival Howard Marsden. Returning home, Bromley spends the following years brooding over his loss.

During this time, he also disguises himself and begins living under a pseudonym. He meets up with Howard and the two discuss radio together, Howard being an enthusiast. But when Cranston meets his old flame Venice, she sees through his disguise. She reveals that her family had decided to pair her up with Marsden and actively sabotaged her relationship with Cranston, preventing his letters from reaching her and instead showing her forged correspondence that implicated him with another woman.

Meanwhile, Cranston has been conducting remarkable experiments, fuelled by a deposit of radon that he found in Afghanistan. He has discovered a way to transport solid objects over radio waves, dissolving a small wooden ball into vibrations and reforming it elsewhere. Raising his ambitions, he successfully gives the same treatment to animal subjects.

Finally, it is time to put his master plan into action. He and Venice elope into the machine, disintegrating into radio waves; as per Cranston’s arrangements, the machine self-destructs behind them. The two lovers are left as vibrations in the ether, destined to take on solid forms only when an inventor of the future hits upon the same device that Cranston created – by which time Marsden will no longer be an issue.

Cranston’s cousin, who received the letter at the start of the story, goes looking for Marsden and finds him an inmate in an insane asylum, obsessively listening to a radio.

The Moon Pool by A. Merritt (part 3 of 3)

The closing instalment of A. Merritt’s novel begins with Dr. Goodwin and his fellow explorers caught up in a conflict between the wicked priestess Yolara and the saintly handmaiden Lakla. As Lakla delves into the history of the land of Muria, it turns out that the struggle goes back to an ancient dispute between a benevolent sun king and an evil moon king.

The closing instalment of A. Merritt’s novel begins with Dr. Goodwin and his fellow explorers caught up in a conflict between the wicked priestess Yolara and the saintly handmaiden Lakla. As Lakla delves into the history of the land of Muria, it turns out that the struggle goes back to an ancient dispute between a benevolent sun king and an evil moon king.

On her side Lakla has not only an army of humanoid amphibians, the Akka, but also the three Silent Ones: members of a half-man, half-lizard race called the Taithu. Dr. Goodwin’s Irish friend Larry O’Keefe declares that these are the Tuatha de Danaan, a race from the legends of Larry’s home country, but the doctor himself is interested more in biology than in myths and concludes that the Taithu and the Akka are each the result of non-mammalian species evolving into sapient lifeforms. “The Englishman, Wells, wrote an imaginative and very entertaining book concerning an invasion of earth by Martians, and he made his Martians enormously specialized cuttlefish”, he notes, by way of comparison.

Lakla reveals that the Taithu were also involved with the battle between the two kings, and were responsible for crafting the mysterious entity known as the Shining One from the ether. The Shining One became corrupted over time – in broad terms, it became a fallen angel – and eventually ended up as the malevolent force encountered earlier in the story.

With Lakla’s infodumps having answered most of the lingering questions about The Moon Pool’s worldbuilding, it is time for the heroes to confront Yolara’s forces before she can invade the surface world. After having tangles with such threats as a gigantic “dragon worm”, they must now face up to the greatest fanger: the Shining One and its army of zombie-like victims, the “dead-alive”. It turns out that the power of love can overcome evil, although the sneaky German villain has one last surprise in store for Dr. Goodwin…

The Moon Pool comes across as a halfway point between the fanciful but not always supernatural adventures penned by H. Rider Haggard, and the sword and sorcery of Robert E. Howard. Merritt takes his protagonists on a journey from the early twentieth century (with all of its geopolitical anxieties) to a land where myth blends with pseudoscience, and along the way, he supplies all the sparkle of dreamlike fantasy to make the transition work.

Poetry

Once again, the issue has some poems by resident versifier Leland S. Copeland:

“Planet Neptune to Mother Sun”

Mother of World, you shine afar

With the feeble light of an evening star;

Your smile is faint as I glimpse your face

Across the millions of miles of space.

Can you recall that destined day

When I left your arms and sped away

To spin my life in the lonely wide? –

Alone till a child moved by my side.

Smaller you grew and dimmer yet

As eons dawned and millennia set,

Till you lived for midgets, Mars and Earth,

Older than I, but younger in birth.

Ages of ages have passed since then,

And time must die ere we meet again,

Yet I send my longing across the night

To dust of my dust and light of my light.

“Alone”

I often think how lonely the Lord of Life must be,

Who made the pneumococcus and poured the starry sea;

Who built a brontosaurus and locked its bones in earth

Ere anthropoid or human had Cenozoic birth.

How lonely, how forsaken, the God of Suns must be,

With neither wife not comrade to share Eternity!

His home quintillions measure, but every else too small,

For suns themselves are motes that dust the Empty All.

I sometimes think how sated the King of Kings must be,

Whose microscopic vision records infinity –

The toils and wars of trillions, while hungry, love, and hope

Unreel the old, old dramas through which the midges grope.

“Of Their Own Have we Given Them”

Iut of a thousand thousand suns,

Into the world and me,

Comes a strength that radiant stars

Age after age set free.

Might of centuries long since dead,

Arriving ray on ray,

Gives to the frame and mind of men

Subtle power to-day.

Out of strife of earthly tribes,

Forth from the moil and me,

Hastens the strength of yesterday,

Seeking Infinity;

Silently darts to glove and star,

Wrapped in darkness or day,

Or sinks in the fluff of nebulae,

Far forever away.

Discussions

In this month’s letters column, Leo Teixeria gushes over the magazine In general:

Magazines as a rule never appealed to my taste, having always found them dry and uninteresting, until the January issue of your Amazing Stories came into my possession and revolutionized my ideas completely. In my estimation, IT IS THE ONE AND UNIQUE MAGAZINE. It deals with matters of a peculiarly interesting nature, and no matter how improbable it is, the story, combined with good educational elements, provides good food for thought.

Other letters are more mixed. Joseph F. Dachowski speaks favourably of the magazine as a whole but criticises The Land that Time Forgot (“It does not have enough scientific fabrication”) and objects strongly to the ending of “The Star of Dead Love” (“Mr. Will H. Gray ought to be shot”). H. H. Currie dismisses most of the short stories as “almost uniformly tedious and not worth their space” but has positive things to say about the longer-form narratives… except for The Island of Dr. Moreau (“Wells, the versatile, seems to be the slave of his imagination., and follows it relentlessly, even to extremes of morbidity”) and The Land that Time Forgot (“Burroughs is too like a Munchhausen”). Patrick Joseph Lydon praises the illustrations of Frank R. Paul (while dismissing most of the magazine’s other artists) before requesting reprints of Ray Cumming’s Science and Invention contributions and Ralph Milne Farley’s Radio Planet stories from Argosy.

Once again, scientific accuracy is something of a bugbear. Edward F. Swensen asks why the device of “The Singing Weapon” could destroy battleships but leave the plan on hich it was mounted undamaged. A.B. Chandler* says that Amazing “beats any magazine published here in England” but complains about the amount of reprints from Science & Invention (“Most of your readers are old readers of that periodical”) and also objects to “The Plague of the Living Dead” on the grounds that its titular ghouls were able to survive without eating (something that would be rectified in later zombie stories).

12-year-old reader Joseph Glottstein finds fault with “The Infinite Vision” (“the closest the telescope could bring the moon would not allow the molecules to be seen”), “The Green Splotches” (citing Einstein to explain that the Jovians’ faster-than-light craft is physically impossible) and The Time Machine (“Sirius is bluish white not green as Wells would have it”).

Cleveland resident T. J. D. praises the magazine before offering good-humoured criticisms of its stories, commenting that readers who notice flaws must generally appreciate the tales (“I’ll bet they really enjoyed themselves, because they were keen enough to catch it”).

Manuel Noble defends a number of the magazine’s stories from charges of implausibility, a criticism which he dismisses as “bigoted”. “They should consider that stories of this type are wanderings into the realm of the imagination and that one guess is as good as another… Stories of this nature should be read with a little allowance for improbability.” He points out that non-fantasy fiction is often just as implausible: “In many of these stories the author only has to apply the magic wand when lo and behold! A long lost relative or hero comes forth, knocks out a dozen villains all at once, and then melts in the arms of the heroine.”

Thomas O’Neill also defends the magazine from critics. “One reader said that Jules Verne’s stories were poorly written and dry. Probably they appeared so to him because he is used to stories more digestible. These come under the head of western and detective stories.”

A number of the letters discuss Wells’ The Time Machine; these are interesting to read today, as they suggest that the readers had failed to grasp concepts of fictional time travel that are commonplace today. “How could one travel to the future in a machine when the beings of the future have not yet materialized?” asks Jackson Beck, while John Church argues that the scene in which the traveller is thrown out of his machine when it suddenly stops should have resulted in his being thrown out of time, rather than landing with a bump in the same era as his vehicle.

T. J. D., after commenting that Wells “has left his natural bent of scientific fiction and has gone in for plain, maudlin stories”, lets his imagination run free:

Let’s suppose our inventor starts a “Time voyage” backwards to about A. D. 1900 at which time he was a schoolboy. […] Will there be another “he” on the [graduation] stage. Of course, because he did graduate in 1900. Interesting thought. Should he go up and shake hands with this “alter ego.” Will there be two physically distinct but characteristically identical persons? Alas! No! He can’t go up and shake hands with himself because you see this voyage through time only duplicates actual past conditions and in 1900 this strange “other he” did not appear suddenly in quaint ultra-new fashions and congratulate the graduate. How could they both be wearing the same watch they got from Aunt Lucy on their tenth birthday, the same watch in two different places at the same time. Boy! Page Einstein!

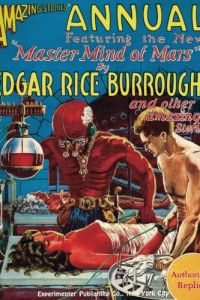

The Master Mind of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs

And so we come to the Amazing Stories Annual, which consists in large part of reprints from the monthly magazine. The greatest hits included within are Austin Hall’s “The Man Who Saved the Earth”, A. Merritt’s “The People of the Pit”, A. Hyatt Verrill’s “The Man Who Could Vanish”, Jacque Morgan’s “The Feline Light & Power Company Is Organized” and H. G. Wells’ “Under the Knife”..But the annual’s flagship story is wholly original: The Master Mind of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs, the latest entry in that author’s popular Barsoom series which began in 1912 with A Princess of Mars.

And so we come to the Amazing Stories Annual, which consists in large part of reprints from the monthly magazine. The greatest hits included within are Austin Hall’s “The Man Who Saved the Earth”, A. Merritt’s “The People of the Pit”, A. Hyatt Verrill’s “The Man Who Could Vanish”, Jacque Morgan’s “The Feline Light & Power Company Is Organized” and H. G. Wells’ “Under the Knife”..But the annual’s flagship story is wholly original: The Master Mind of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs, the latest entry in that author’s popular Barsoom series which began in 1912 with A Princess of Mars.

Instead of series regular John Carter, the hero of this novel is Ulysses Paxton, a soldier of World War I who – like Carter – finds himself suddenly transported to Mars during a battle. He ends up in the dubious care of Ras Thavas, a Martian surgeon of great genius but no empathy or morality, being instead driven by a steely scientific mind. While there, Ulysses is granted the Martian name of Vad Varos by the surgeon.

Thavas has a particular interest in brain transplants, and so an evil queen named Xaxa hired him to prolong her life by placing her brain into the head of a much younger woman. Ulysses falls in love Valla Dia, the woman who has swapped brains with Xaxa. Once the Martian equivalent of Helen, with armies having gone to war over her beauty, Valla now inhabits the queen’s elderly body.

Eventually, the elderly Thavas’ body begins to fail him. The only person who can save him is his protégé Ulysses, who has by now studied for long enough to be able to transplant Thavas’ brain into another body. Ulysses agrees to do so – on the condition that Thavas give Valla her body back. Thavas reluctantly agrees, although it falls upon Ulysses to retrieve Valla’s body, its new occupant Queen Xaxa having long since departed back to her homeland.

Embarking on his quest, Ulysses teams up with two of Thavas’ test subjects: Gor Hajus, a former assassin; Dar Tarus, who has a grudge of his own against Xaxa; and Hovan Du, an ape with a half-human brain. After a number of scrapes, and a period spent in the land of a prince named Mu Tel, the band manage to thwart Xaxa and return Valla Dia to her true body.

The novel features all of the swashbuckling adventure that readers had come to expect from Burroughs, and manages to fit a number of intriguing ideas into its narrative. It is easy to imagine Gernsback approving of the science fiction concepts on offer, both the main conceit of brain transplants and smaller details such as the sequence discussing the communication technology of Mars.

Burroughs also finds room to include a degree of social satire. Mu Tel’s people have a proto-Randian philosophy: “They believe that no good deed was ever performed except for a selfish motive… They hold that the only sin is failure—success, however achieved, is meritorious”. This is depicted as a cultural flaw that echoes the mindset of Ras Thavas, who – in the best mad scientist fashion – scorns all sentimentality. Ulysses then goes from one extreme to another when he enters the religiously fundamentalist realm of Xaxa. The citizens of this land worship a god named Tur; their sacred utterances include “Tur is Tur” and “Tur is Tur” (Ulysses points out that these are the same, but is informed that they are, in fact, reversals of one another). The novel’s climax has Ulysses duping these fanatics by masquerading as the god Tur. This is not a tale of Swiftian cynicism, however, and the love between Ulysses Paxton and Valla Dia wins out over the two evils of heartlessness and mindlessness.

“The Face in the Abyss” by A. Merritt

The annual has one other tale that is new, if only to the pages of Amazing Stories: A. Merritt’s “The Face in the Abyss”, which had run in Argosy but had never before appeared in Amazing. Here, Merritt uses much the same materials that he put to use in The Moon Pool to create another lost world fantasy.

The annual has one other tale that is new, if only to the pages of Amazing Stories: A. Merritt’s “The Face in the Abyss”, which had run in Argosy but had never before appeared in Amazing. Here, Merritt uses much the same materials that he put to use in The Moon Pool to create another lost world fantasy.

While on a treasure-hunting expedition in a remote corner of the Andes, adventurer Nicholas Graydon witnesses his companion Starrett drunkenly assaulting a native girl. After Graydon rescues the girl from his caddish cohort, she introduces herself as Suarra, a denizen of Yu-Atlanchi; discussing the culture of her homeland, she shows him a bracelet with a bas-relief image of a half-woman, half-snake creature being held aloft by dinosaurs.

She offers to show Graydon a way out of the obscure area, and presents him with treasures as part of the bargain, so long as he leaves his three companions behind. He turns down her offer, even though he mistrusts the other travellers (“These men are of my race, my comrades”).The other two members of the expedition, Soames and Dancret, are incredulous when they hear that Graydon let the treasure-laden girl return to her own kind instead of taking her as a hostage. Regarding him as a traitor, they hold him captive.

Then Suarra returns, accompanied not by bands of warriors as Graydon’s cohorts feared, but by a single attendant and a white llama laden with treasures. She takes the explorers on a trip to her home of Yu-Atlanchi, and along the way the band witness a bizarre hunting expedition: the hunter rides a dinosaur rather than a horse, and instead of dogs he uses smaller dinosaurs. His [quarry, meanwhile, is a half-spider, half-man creature. Graydon spends some time pondering what evolutionary process could have created such a being.

Fear of the unknown battles with lust for treasure amongst Graydon’s companions, but the latter wins out. When the treasure-laden llama runs off, Starrett shoots and injures the animal, incurring the wrath of the locals.

The four end up as prisoners, but Graydon retains the trust of Suarra. She explains that the inhabitants of this land are immortal, and she yearns to visit the outside world where children exist: “in Yu-Atlanchi not only the Door of Death but the Door of Life is closed. And there are few babes, and of the laughter of children—none.” Furthermore, the immortals of Yu-Atlanchi obtained their knowledge from a race of serpent people; there is only one surviving member of this species, known as the Mother.

In the depths of Yu-Atlanchi, the men are confronted with an enormous stone face, “Luciferian, imperious; ruthless—and beautiful”. The face exerts a psychic hold over the travellers, promising them worldly power.

Fortunately for Graydon, the Sanke-Mother turns up at the behest of Suarra; although he glimpses the being only briefly, this is enough to free him from the face’s influence. Meanwhile, the other three men are converted into molten gold, joining the treasures they sought to plunder. Suarra herself then arrives on the scene, along with a flock of flying lizards, and Graydon falls unconscious…

The version published in Amazing contains a framing device omitted from the later novel, where an unnamed narrator meets Graydon as the explorer is on his deathbed, ready to relate the tale of his voyage to Yu-Atlanchi. Merritt would later remove this from his novel-length expansion of the story.

*Publisher’s Note: That would be the 15 year old A. Bertram “Jack” Chandler of Rim Worlds/John Grimes fame. It would be a few more years before he would take to sea, emmigrate to Australia, begin writing fiction at the behest of John Campbell and eventually have a major (Australian) award named in his honor. Fortunately for us, that’s not a unique story when it comes to the readers of Amazing Stories.

Publisher’s additional crassly commercial note:

Facsimile editions of the Amazing Stories Annual are available from Futures Past Editions (this is the Authorized Replica – accept no substitutes!)

Facsimile editions of the Amazing Stories Annual are available from Futures Past Editions (this is the Authorized Replica – accept no substitutes!)

and

The Best of Amazing Stories the 1927 Anthology contains the best stories of the year!

The Best of Amazing Stories the 1927 Anthology contains the best stories of the year!

Read My Profile