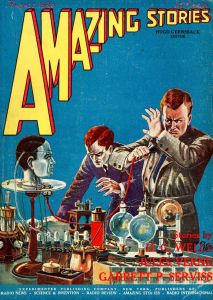

A replica human head sits on a glass dish. Its face is an unnatural blue and a crack runs above its eyes, suggesting a lid. Tubes and wires connect the head to an elaborate electrical apparatus. Two men, one of them holding part of the apparatus, react in horror to the head before them. It was August 1926, and readers would have to pick up Amazing Stories #5 to find out exactly what those men were so disturbed by.

A replica human head sits on a glass dish. Its face is an unnatural blue and a crack runs above its eyes, suggesting a lid. Tubes and wires connect the head to an elaborate electrical apparatus. Two men, one of them holding part of the apparatus, react in horror to the head before them. It was August 1926, and readers would have to pick up Amazing Stories #5 to find out exactly what those men were so disturbed by.

In this month’s editorial, Hugo Gernsback continues his ruminations about seeming impossibilities in scientifiction. Citing insects that can survive for years without food, and fish that can be revived after being frozen, he speculates on the possibility of alien lifeforms that can exist without oxygen: “If there is life on the moon, and I for one really believe there is, then whatever life there is must go on with practically no air.” These thoughts were possibly inspired by the moon-people of Station X, which began serialisation in the previous issue.

A Columbus of Space by Garrett P. Serviss (part 1)

The main characters of this 1909 novel are members of a gentlemen’s club. One, Edmund Stonewall, has invented a spacecraft and decides to take his friends – including the narrator – on a trip into the heavens. The influence of Verne and Wells is palpable, although Serviss uses neither Verne’s oversized gun nor Wells’ anti-gravity material. Instead, he establishes that his fictional craft is fuelled by atomic power, a new concept at a time when Ernest Rutherford’s research was still in its early days:

The main characters of this 1909 novel are members of a gentlemen’s club. One, Edmund Stonewall, has invented a spacecraft and decides to take his friends – including the narrator – on a trip into the heavens. The influence of Verne and Wells is palpable, although Serviss uses neither Verne’s oversized gun nor Wells’ anti-gravity material. Instead, he establishes that his fictional craft is fuelled by atomic power, a new concept at a time when Ernest Rutherford’s research was still in its early days:

[L]ook at the time that [humans] have wasted upon such petty forces as steam and ‘electricity,’ burning whole mines of coal and whole lakes of oil, and childishly calling upon winds and tides and waterfalls to help them, when they had under their thumbs the limitless energy of the atoms, and no more understood it than a baby understands what makes its whistle scream! It’s inter-atomic force that has brought us out here, and that is going to carry us a great deal farther.

The ship’s interior has a living area so cosy that the club members are able to puff on tobacco, comfortable in the knowledge that the smoke will be converted into atomic fuel for the vessel. Ah, if only the splitting of the atom in reality was such an urbane affair.

After a tussle with some meteors the craft arrives at Venus, where the men catch sight of an alien “shaped like a man, but more savage than a gorilla”. Speculating that the Venusian race will ”turn out to be at least as intelligent as our African or Australian savages”, the explorers pursue the alien to a cave inhabited by its clan.

The Venusians show hostility, prompting group leader Edmund to shoot one of them dead as a warning to the others. He shows remorse – “I’m sorry now that I aimed at that fellow, the sound alone would have sufficed” – which intensifies when he witnesses a tearful Venusian woman with two children, possibly the dead alien’s family. “I wish I had never come here… The first thing I have done is to kill an inoffensive and intelligent creature.” His companions Jack and Henry, meanwhile, try to persuade him that anyone would have done the same in his position.

Spending time with the placated Venusians, the explorers learn that the aliens worship the Earth, and the narrator is nearly sacrificed to this deity before Edmund steps in by shooting the alien priests dead. “I’m sorry to have had to begin killing right and left again,” he says, “but I guess that’s the lot of all invaders”. Despite this altercation the humans maintain good relations with the locals, learning to communicate using a form of telepathy and convincing some of the Venusians to accompany them on a journey across the planet. Alas, most of these space-age native bearers end up getting swept to their presumed deaths in a flood. The first instalment of the novel ends with the band encountering a second humanoid race on Mars: blond-haired, blue-eyed and led by a beautiful Amazonian queen.

“A Columbus of Space”, somewhat awkwardly, mixes Vernean voyages of scientific elucidation with a clearly fantastical vision of alien life. Venus itself is portrayed as a wondrous land where mountains of ice act as gigantic prisms, refracting the light of the sun. The characters discuss the effects of Venus’ atmosphere on their voices, or how the presence of coal indicates that the currently barren planet must once have had vegetation. Much is made, meanwhile, of the fact that one half of Venus always faces the sun, while the other is in perennial night.

But Serviss shows less imagination when it comes to realising his aliens, instead falling back on stock types familiar from adventure and fantasy fiction. The ape-like people inhabiting the dark half of Venus are colonial clichés that would be familiar to readers of H. Rider Haggard, while the population of the light side – the Ariels to the dark-side Calibans – are plucked directly from classical iconography, right down to their quasi-Grecian dress.

Station X by G. MacLeod Winsor (part 2)

In the second instalment of this novel about aliens contacting Earth through radio, sometime protagonist Macrae comes under the mental control of the hostile Martians – themselves the result of a body-swapping invasion from Earth’s moon. Professor Rudge, acting on behalf of the benevolent Venusians, must apprehend him before coming up with a means of halting any further psychic attacks from Mars.

In the second instalment of this novel about aliens contacting Earth through radio, sometime protagonist Macrae comes under the mental control of the hostile Martians – themselves the result of a body-swapping invasion from Earth’s moon. Professor Rudge, acting on behalf of the benevolent Venusians, must apprehend him before coming up with a means of halting any further psychic attacks from Mars.

On one level Station X is trying to offer an convincing portrayal of first contact with an alien intelligence, but it never really commits to this. The Venusians give Rudge an advanced set of physical theories, ones that overturn vast chunks of contemporary human understanding…but these are too complex to be passed on to the reader. We learn that Venus has achieved a near-Utopia, “ideal beyond the previous dreams of what any state could be”, but this is – alas – impossible to emulate on Earth: “it would be worse than useless here, spelling absolute anarchy.” H. G. Wells would have analysed the aliens’ thought and society head-on; G. MacLeod Winsor settles for simply telling us that their thought and society is advanced without actually demonstrating this.

Macrae’s possession by a Martian intelligence has its roots in the pseudoscience of spiritualism: although mediums traditionally favour earthbound ghosts, the likes of Hélène Smith have claimed contact with aliens. While it makes token gestures towards the awe of scientific discovery, Station X is – thus far, at least – trading primarily in the eeriness of mystery.

“Doctor Ox’s Experiment” by Jules Verne

In this novella, originally published in 1872 as “Une fantaisie du docteur Ox”, Jules Verne takes a break from his far-flung adventures and introduces us to the small Flemish town of Quiquendone. Here, the main industry is the production of whipped-cream and barley sugar – confections which are consumed on the spot rather than exported, thereby making the town entirely self-sufficient. There are no arguments or political disputes here, so placid is the population of Quiquendone.

In this novella, originally published in 1872 as “Une fantaisie du docteur Ox”, Jules Verne takes a break from his far-flung adventures and introduces us to the small Flemish town of Quiquendone. Here, the main industry is the production of whipped-cream and barley sugar – confections which are consumed on the spot rather than exported, thereby making the town entirely self-sufficient. There are no arguments or political disputes here, so placid is the population of Quiquendone.

Meanwhile, one Dr. Ox (“a regular oddity out of one of Hoffman’s volumes”) has arrived and prepares to carry out an experiment, the phlegmatic Flemish of Quiquendone being the ideal guinea pigs. He does not bother to tell anybody about his plans – but then, as he asks his assistant, “What would you say if the dogs or frogs refused to lend themselves to the experiments of vivisection?”

The doctor’s scheme is to test the effects of certain gases upon the human psyche. And so, he saturates the town with pure oxygen, causing the once tranquil locals to become agitated. They begin to argue, break out into fights and finally arrive at the brink of war – until the doctor’s gasworks explode, bringing an end to the experiment.

“Are virtue, courage, talent, wit, imagination – are all these qualities or faculties only a question of oxygen?” asks the narrator. Dr. Ox clearly thought so, although Verne wryly leaves the final conclusion to the reader. For all its whimsy, the story demonstrates a sharp lack of sentimentality.

“The Empire of the Ants” by H. G. Wells

A gunboat in the Amazon receives a strange mission when it is forced to deal with a plague of ants. These are no ordinary ants, however. They are a large species, reaching upwards of four centimeters in length; they are carnivorous; and they deliver a deadly poison.

A gunboat in the Amazon receives a strange mission when it is forced to deal with a plague of ants. These are no ordinary ants, however. They are a large species, reaching upwards of four centimeters in length; they are carnivorous; and they deliver a deadly poison.

This in itself would be cause for concern, but the situation proves to be graver still when it turns out that the ants are unusually intelligent. They have leaders, capable of organising followers. They appear to wear rudimentary clothes. And it is possible that their poison is nothing less than a manufactured weapon…

The story’s audience identification character is Holroyd, an English engineer on board the gunboat. He has no truck with his jungle surroundings, has trouble communicating with the South American crew, and would prefer to be back amongst the tidy hedgerows of his own country. His is a classically Wellsian protagonist: a loving portrait of provincial English normality, who becomes quirky and out-of-place when set against the world-changing developments of science fiction.

Also quintessentially Wellsian is the anti-imperialist subtext. Like the Martians in The War of the Worlds, the ants are stand-ins for European colonialists, with the irony that Europeans are the targets of their subjugation: although the narrative takes place in South America, the apocalyptic endings has the ants poised to drive humanity out of Europe within a few decades. With the story inviting us to draw comparisons between humans and insects, the double meaning of the title becomes hard to miss.

“The Talking Brain” by M. H. Hasta

Harvey, a university professor, becomes embroiled in the experiments of his eccentric colleague Murtha. The latter conducts a strange experiment to gauge the effects of emotion on the body’s resistance to electricity; this involves running a light charge through Harvey while reading a passage from Shakespeare, all without Harvey’s consent. Professor Murtha is himself seemingly emotionless, and his colleagues come to resent his using them as guinea pigs.

Harvey, a university professor, becomes embroiled in the experiments of his eccentric colleague Murtha. The latter conducts a strange experiment to gauge the effects of emotion on the body’s resistance to electricity; this involves running a light charge through Harvey while reading a passage from Shakespeare, all without Harvey’s consent. Professor Murtha is himself seemingly emotionless, and his colleagues come to resent his using them as guinea pigs.

Despite his oddities, Murtha possesses scientific genius. Through artificial retinae, he is able to partially restore the vision of a sightless rabbit. A blind student, Vinton, requests to undergo a similar procedure; as Murtha sets to work, protagonist Harvey leaves the country on a polar expedition.

Upon his return, Harvey receives an invitation to Murtha’s laboratory. He finds that Vinton was seriously injured in a car accident, and that Murtha resorted to desperate measures to save his life. In secret, he removed Vinton’s brain and placed it into the wax likeness of a head, kept alive through electric currents. By sending electrical impulses, the disembodied brain is able to communicate through Morse code – and begs to be killed. Murtha and Harvey briefly discuss the morality of this act, before concluding that it would be kindest to put Vinton out of his misery.

In this story, M. H. Hasta offers a relatively early specimen of the mad scientist concept, one with possible homages to earlier treatments of the theme: the detail of the polar expedition recalls Frankenstein, while the usage of a wax head is similar to Lovecraft’s “Herbert West – Re-Animator”. Much of the story is a character sketch of Professor Murtha, following his decline from socially awkward but inspired scientist to a man so absorbed in his own research that he has lost all sight of the moral angle.

“High Tension” by Albert B. Stuart

Dr. Reginald Carter is a man of immense surgical skill, but little sociability. “You were a very interesting case,” he tells one of his patients. “You are well now and therefore of no further interest. Our relations were of a purely business nature and call for no payment beyond the bill I have rendered you.”

Dr. Reginald Carter is a man of immense surgical skill, but little sociability. “You were a very interesting case,” he tells one of his patients. “You are well now and therefore of no further interest. Our relations were of a purely business nature and call for no payment beyond the bill I have rendered you.”

One of Carter’s colleagues, Dr. Bryan, is approached by the police for help with a baffling murder case. The only mark that the police could find on the victim’s body is a circular bruise around the wrist. Taking a closer look, Bryan realises that the man has a broken neck – and yet whatever caused this left no more than a thumb-sized bruise near the hair-line. It appears that the murderer is a person of superhuman strength, capable of breaking a man’s neck with no more than a press of the thumb.

Bryan comes to suspect Carter after witnessing him exhibit unusual strength, and confronts him. Carter pleads that the homicide was justifiable: he explains that he is descended from Russian nobility, and that his victim was a sometime Bolshevik who had tortured him and (it is implied) killed his family.

Carter then reveals that his incredible strength is due to an electric apparatus he carries with him: “I found that when this high frequency current of mine was concentrated on a certain area of my brain, I not only had a greatly increased mental capacity, but I could also make use of the inherent power in my muscles.” His irritable nature was a side-effect of this process. The story ends when Carter accidentally gives himself a fatal electric shock while demonstrating his invention to Bryan.

“High Tension” makes for an appropriate companion piece to “The Talking Brain”. Dr. Carter has obvious similarities to Professor Murtha, each being a reclusive scientific pioneer with a sinister secret. In addition, both stories reflect an interest in the science of electricity, a recurring theme in early Amazing – which did, after all, share an editor and a general ethos with Modern Electrics. Another similarity is that both stories are original acquisitions from authors who swiftly vanished from the world of science fiction.

“The International Electro-Galvanic Undertaking Corporation” by Jacque Morgan

Electrical engineering forms the backbone of another story, this one reprinted from a 1912 issue of Modern Electrics.

Electrical engineering forms the backbone of another story, this one reprinted from a 1912 issue of Modern Electrics.

Mr. Fosdick has hit upon a new idea for a business venture: he will start a company to electro-plate corpses, transforming the deceased into metallic statues – an aesthetically appealing new way of commemorating loved ones. “Just think what a handsome place the new cemeteries will be on a sunny morning. Copper, nickel, silver and gold statues all sprinkled about. Cheerful is no word for it! Why, man, they’d become amusement parks!”

Alas, as there have not been any deaths recently, Mr. Fosdick is at a disadvantage when it comes to putting his idea to the test. Undeterred, he decides to try the process out on his still-living associate Mr. Stetzle. The latter man is, to say the least, unhappy with this state of affairs.

Other than a very of-its-time racial gag involving Stetzle’s face being blackened with graphite, this is a good-humoured farce with a touch of social satire: Fosdick aims for the metal-plated corpses to use either copper, nickel, silver or gold, depending on the client’s budget range. It also marks Fosdick’s final appearance in Amazing, even though Morgan had written two further adventures for the character in Modern Electrics.

And finally…

In an Amazing Stories first, the issue contains a piece of verse: “Aspiration” by Leland S. Copeland, a poet whose work would be printed by Amazing in fits and starts until 1929.

Over the dark, thin nebular drift,

Waiting the warmth and light;

Over the writhing, blazing sun,

And planets, half day, half night;

Comets that race with a trail of fire,

Asteroids whirling along—

Something is brooding, impelling;

Something that cannot be wrong.

Up from the unseen germ and cell.

Potent with glory unborn;

Up from the fish of the Devon sea.

And saurians feeding at morn;

Jungle glooms where the lion lurks,

And dark-eyed cave girl’s song—

Something is moving, compelling;

Something that cannot do wrong.

A recurring theme in Amazing Stories #5 is the alteration of the human mind. Verne gives us mind-altering gas; Winsor deals with alien mind-control; Stuart covers the mind (and body) being altered by an electric current; and Hasta has a mind existing outside of a body. Two of the other stories have related themes: Morgan’s tale depicts the alteration of the human body through electricity, while Wells follows the minds of ants being altered through evolution.

Also notable is how, between them, the issue’s stories balance down-and-dirty usage of electricity (Stuart, Hasta, Morgan) and gas (Verne) with Serviss and Winsor’s fanciful accounts of human contact with aliens.

Read My Profile

Recent Comments