This will be the final “redux” entry for NaNoWriMo, as November ends in less than a week. Has it been successful for me? In terms of plot, yes. In terms of actual writing, not as much as I’d hoped. But I guess it takes as long as it takes. And before I forget, a happy belated Thanksgiving to all Americans; I hope your turducken (or tofu turkey for veggietarians) was good. And I hope you gave proper thanks for all the good stuff in your lives! And now, back to the Ace Doubles and their cover artists.

I had initially thought I could cover all the cover artists for the Ace Doubles who did a half-dozen or more in one column; then I realized I hadn’t even finished with the main artists in the previous entry! Not to mention that not all the cover artists are discoverable, even with the help of the interweb and all its tubes. Besides, I can include only so many illustrations here, so covering a 30-year span means I have to be choosy. A number of cover artists only did one cover; I won’t even get to some of them. Forgive me, dear reader, if the cover artists I speak about are the ones I feel deserve a mention. I should say, if I haven’t already, that I love most published SF/F art, but I have certain favourites. Some I’ve been lucky enough to get to know (and some to call “friend”), but for some I will never have that opportunity. But I appreciate most of them. I cannot begin to list the artists I love most dearly (as artists), and I would certainly offend some who are friends by leaving them off the list, so I won’t even try. I will, however, mention a few here whom I particularly like (or love, artistically speaking).

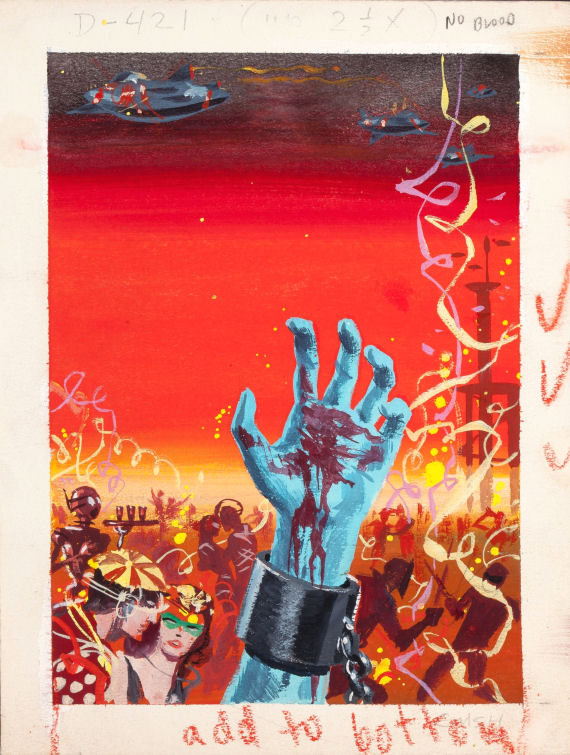

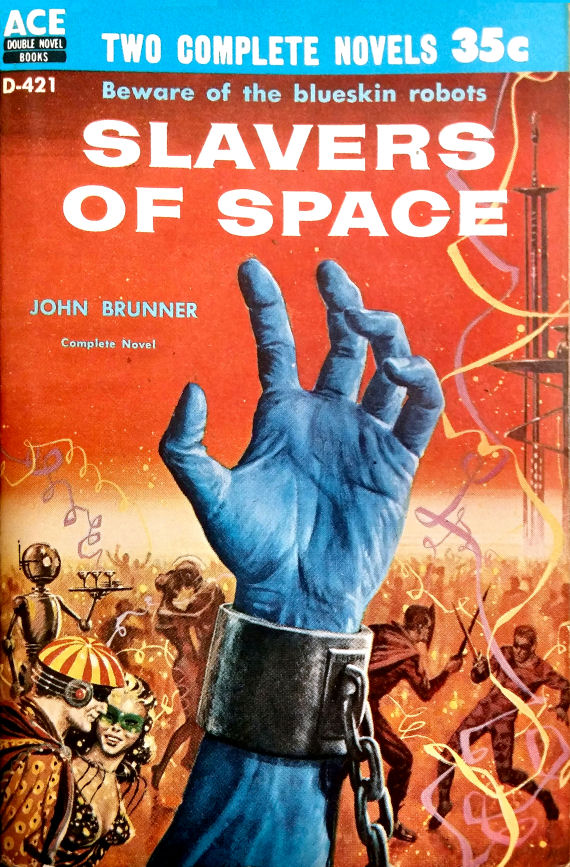

When I linked to Dr. Smith’s web page (https://people.uncw.edu/smithms/ACE_doubles.html, in case you don’t remember) last week, I forgot to mention one salient fact: that students or lovers of SF art — not just Ace Doubles art, though this is specific to it — might really enjoy his links to some scans of cover “roughs” by a number of artists. If you’re curious about how a piece comes to be a cover, these will give you some idea of how it worked in the past (I’m not sure how it has changed in the digital age). My information comes from talking to artists like the late Kelly Freas, the late Alex Schomburg and the very much alive (but retired) George Barr, so it might be out of date.

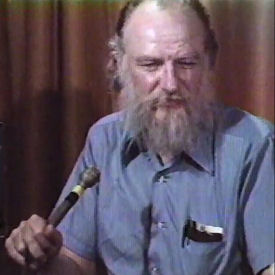

Very basically, the AD (Art Director) will assign a cover to an artist, who then produces several preliminary sketches, or roughs, and the AD will select one, which the artist then turns into a finished cover. (Does the artist read the book before doing the cover? Usually, when they’re allowed to. I’ve been told that artists are sometimes only given a précis of the book.) The cover will sometimes need revision after it’s finished, but not too often — that’s why the roughs are made. On the D-series page of Dr. Smith‘s website, there are both pencil sketches and colour roughs by EMSH (Ed Emshwiller, shown in Figure 1) for various books, as well as scans of actual cover art; other original art and roughs are on his other series pages (see Figure 2). A boon to the lover of SF art and the academic/student! Figure 3 shows the published paperback cover, for comparison with the rough. Some years before his death, Ed left SF illustration to go into the nascent field of video imagery, and won several awards. Video`s gain was SF`s immeasurable loss!

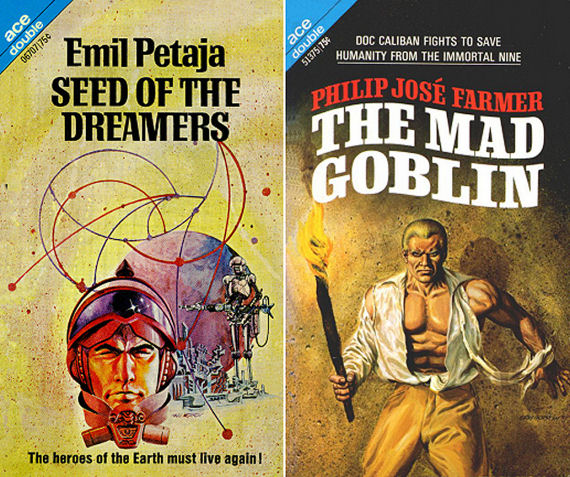

Getting back to the artists, I didn’t get to one of the more prolific cover artists, Grey Morrow, last week. Morrow was primarily a comic book/strip/graphic novel-type artist. As such, his figures were often not as well-drawn (in my opinion) as some of the other artists’ were — anatomically, they weren’t always correct, and sometimes the poses were very awkward; one example (not shown here) was 51375, the Tarzan-like figure for Philip José Farmer’s Lord of the Trees (the book is either an homage to Tarzan or a parody it). Because Farmer did the same thing with Doc Savage (a book about “Doc Caliban”), I think Morrow felt comfortable doing the same with his cover; shown in Figure 4 right is Morrow’s “homage” to the Doc Savage covers by James Bama on Bantam Books’ paperbacks. Figure 4 left shows that Morrow could, and did, do competent SFnal covers; this one is vague enough, however, to work for any number of books. In short, Morrow did 15 covers over a three- or four-year stint (1966 or 1967 through Sept. 1970).

Another artist who did 7 covers was Jerome Podwil. Podwil, unlike so many of the artists who did Doubles covers, is still alive, though according to what I could find out, he’s not doing paperback covers right now. I consider his Ace Double covers to be uninspired, although competent commercial art. So I’m not going to show you one; you can go to Dr. Smith’s page for a look at a couple of thumbnails. (If that sounds mean of me, consider that every cover picture I publish has about an hour’s cleanup work at best. The worst you don’t even want to hear about; I nearly have to repaint it myself!) Podwil did covers for the G, H and M series (around 1965-1966).

And now we come to many people’s favourite Ace Doubles cover artist: Jeffrey Jones! Born Jeffrey Durwood Jones in 1944, Jeff graduated from a Georgia university and began painting paperback covers in the mid-1960s; although Jones only did 6 Ace Doubles covers, the number of other covers he painted for paperbacks was somewhere around 150, plus tons of black and whites, comics, etc. Jones painted in a classic style, and became renowned for fantasy work; examples of both the fantasy and the SFnal styles are in Figure 5 below. She was featured in National Lampoon and Heavy Metal frequently as well as many other respected publications. Tragically, although she was able to transition from male to female — becoming Jeffrey Catherine Jones in the process — her personal life brought her no peace, and she died of heart failure complicated by lung problems a few years ago. She was perhaps the most classically “painterly” of all the Ace Doubles cover artists. It’s reported (Wikipedia) that Frank Frazetta called her the “greatest living painter.” I never met her, but we were Facebook friends, and I respected her art and her artistic merit.

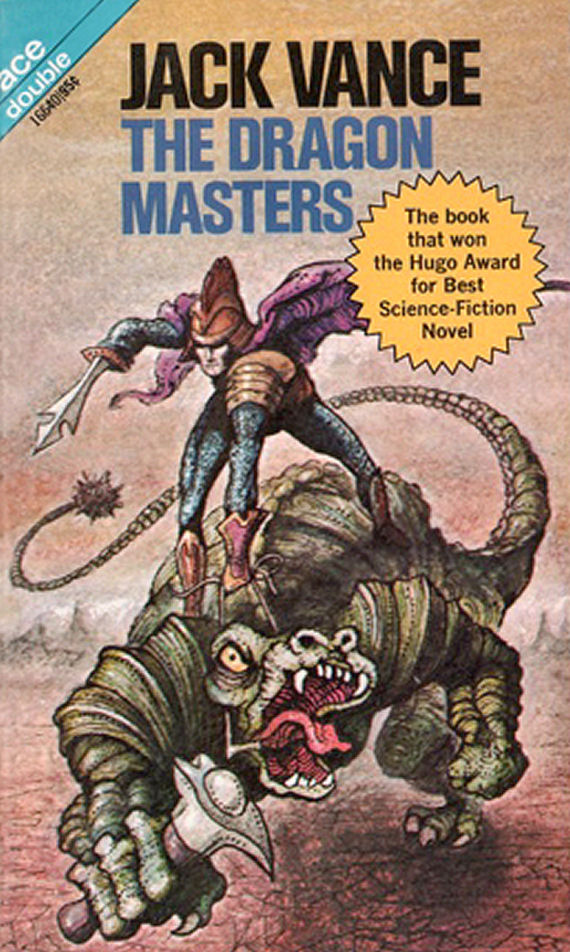

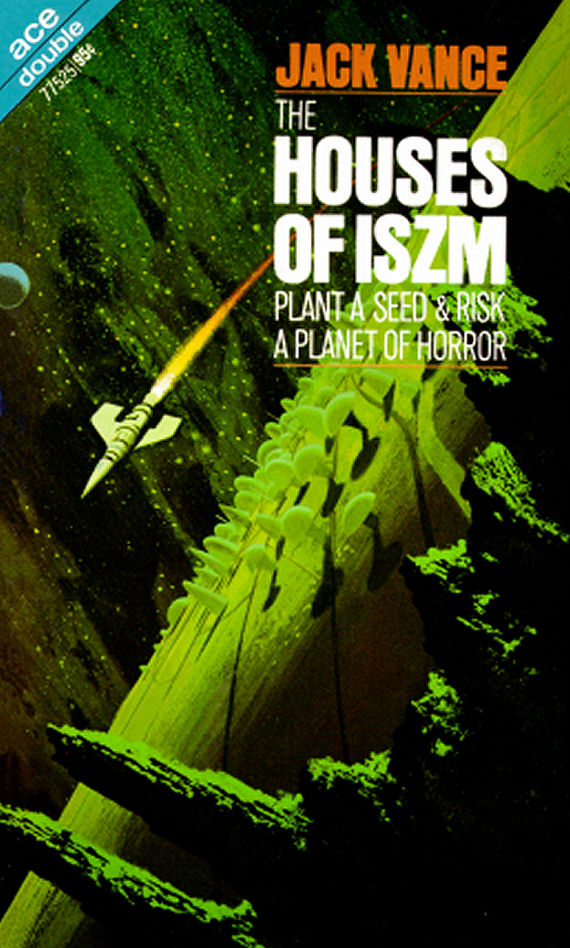

Another artist who’s a favourite of mine, Josh Kirby, also did six Ace Doubles covers. (I had never known until recently that his real name was Ronald William Kirby and, according to Wikipedia, he acquired the nickname “Josh” at the Liverpool School of Art from having his work compared to the great Joshua Reynolds’ work. Although most people now would probably remember his work from the Terry Pratchett Discworld series of paperbacks — at least the British ones — he painted, besides his six Ace Doubles covers, around 200 other paperback covers for various publishers. An example of his Ace Doubles work is shown in Figure 6.

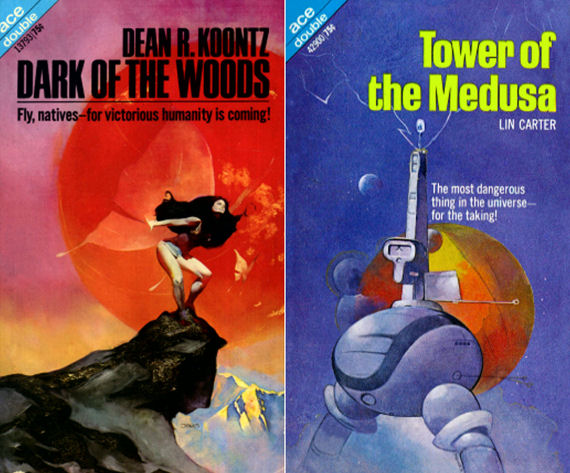

Another artist whose work was competent as far as commercial art but, to me, entirely uninspiring and forgettable was Harry Bergman, who did four Ace Doubles covers. I’ve been unable to find any information on Bergman or his art, except for some images on Google. For those who wish to pursue it further, they should look for the Philip K. Dick Ace Double (15697) comprising Dr. Futurity and The Unteleported Man. The next most prolific, with four covers, is Michael Whelan, another favourite artist of mine. Whelan did a number of “two books in a single volume,” as in Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Planet Savers and The Sword of Aldones, but since these books were not published in the familiar tête-bêche format, I don’t consider them Ace Doubles. Dean Ellis, another very popular “space” artist, did only three Ace Doubles, although he did covers for other books and many magazines. In my opinion, he — along with Valigursky (see last week’s column) — was one of the few people who did space art reminiscent of the great SF films, including 2001. Figure 7 shows the kind of art Ellis was famous for (another familiar artist, who as far as I know never did an Ace double, was Vincent di Fate; his art is very reminiscent of Dean Ellis’s).

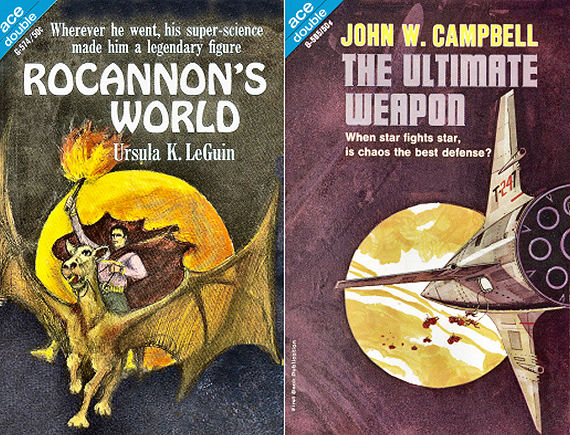

Finally, we come to those people who, for some reason or another, did only one or two covers. I don’t know who — whether it was Donald Wollheim or his Art Director(s) — selected who should do cover art, or how many covers each was allotted; the story behind that would be interesting to say the least! Two artists who only did two covers each — one I’m showing, one I’m not — were Gerald McConnell and Peter Michael. Michael’s art (see G-606, Lin Carter’s Man Without a Planet) was commercial art by someone who knew nothing about SF and cared less, in my opinion. G-606 shows a man with some kind of glass dome — like a ‘50s space helmet from a cheap SF movie — over his head; the other one (G-632 Mack Reynolds’s The Rival Rigelians) shows three nearly formless people in what one assumes are space suits looking down at the viewer with arms raised in alarm; behind is a red moon and a yellow sun. Neither picture is particularly well painted, which is why I’m not showing either one here. The covers by McConnell are puzzling, to say the least (see Figure 8). The right-hand cover, for John W. Campbell’s The Ultimate Weapon, is a fairly standard, but well-executed SFnal cover; not exciting, but at least well done. The other, for Ursula LeGuin’s Rocannon’s World, is so badly executed that it appears the Art Director — or whomever — just took the cover rough and used it instead of allowing the artist to finish the piece. Could it have been a deadline issue? I guess we’ll never know.

And the last three artists I’d like to mention are George Barr — who is no longer doing cover art, enjoying a well-earned retirement — Vaughn Bodé and, finally, Alex Schomburg. I won’t publish the Barr cover here (71082, E.C. Tubb’s Lallia), because the actual art was reduced to the size of a postage stamp and placed in the middle of a black background covering the rest of the book save for the Ace logo, a blurb informing the reader it’s a “Dumarest” book, the author’s name and the book title. It’s embarrassing; and until I had to research this piece, I didn’t know that was a George Barr, who has a reputation for well-done fantasy and science fiction art. (He’s a devotée of ‘40s and ‘50s art, one can tell from his other SF work, but this cover doesn’t show it, and almost doesn’t show. Barr also did the frontispiece in his signature careful black-and-white style; Smith’s website erroneously credits the cover and frontispiece to artist Ken Barr, although the book itself does credit George properly.

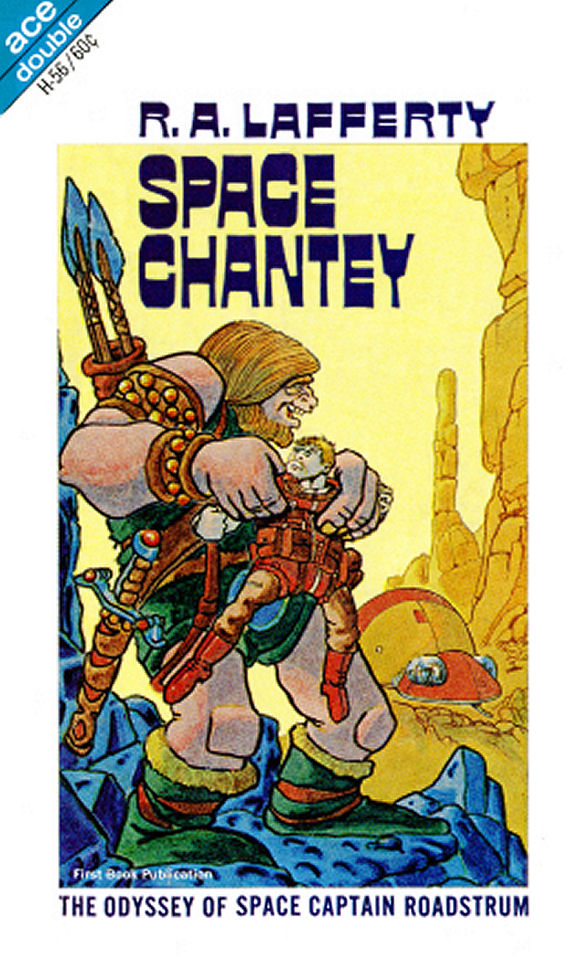

Vaughn Bodé was well known for his Cheech Wizard comics, published in National Lampoon, and his style of cartooning is very obvious from Figure 9, for R.A. Lafferty’s Space Chantey (H-12). Bodé was enormously popular from both Lampoon and underground “comix”; it’s quite probable that he was also a significant influence on Ralph Bakshi’s film Wizards — although I don’t know whether Bakshi ever admitted it. It may be that it was too “cartoony” for Ace; whatever the reason, the Lafferty book is the only Ace Double Bodé ever did the cover for. His son Mark is carrying on the family tradition, painting in an almost exact copy of his father’s style, but updating venues and subjects to today. And, finally, we come to one of my favourite SF artists of all time: Alex Schomburg (which is not to detract from any of my other favourite artists of all time).

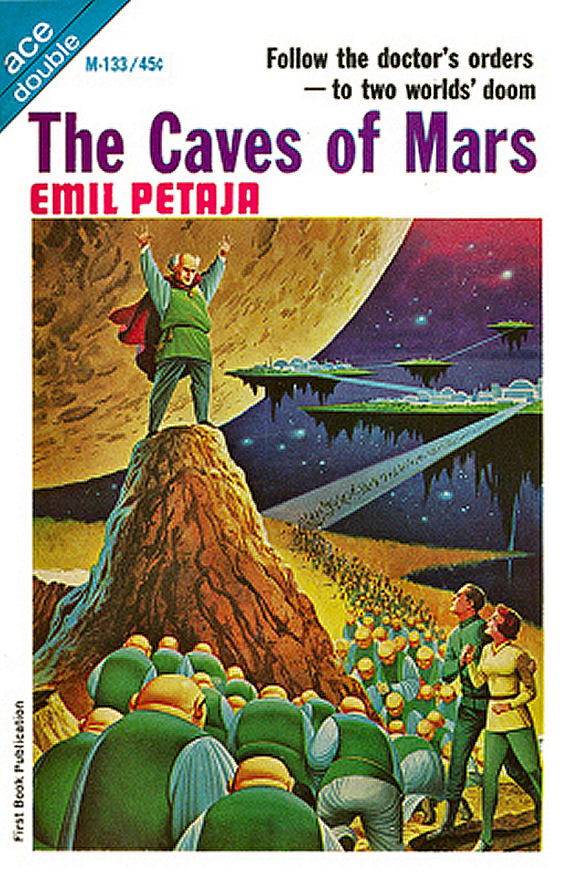

Alex Schomburg worked, as he told me, for Hugo Gernsback back in the Radio Craft days; after, he began illustrating interiors for Thrilling Wonder Stories, then became a cover artist with Startling Stories in 1939. He became a significant comic book artist during the 1940s, doing many hundreds of covers for Human Torch, Captain America and other Marvel staples, although it was then Timely publications, not Marvel. In the 1950s, he went back to magazine illustration, doing dozens of covers in his signature smooth airbrush style. He also did the end papers — illustrating science fiction itself! — for the John C. Winston hardcover series of juvenile SF novels, as well as many of the covers for the same; the only Ace Double he illustrated — although he did at least one Ace single — was Emil Petaja’s Caves of Mars. I used to own the original cover rough for this book, which was — except for size — almost identical to the cover; I had to sell it some years ago when I underwent a period of financial hardship. But I had the pleasure of viewing it for some years, as well as the extreme pleasure of Alex’s friendship for many years. I have told the story of the Winston juveniles in a previous Amazing Stories column; if there is any interest, I could revisit that column some time in the future.

My thanks go to Dr. Michael S. Smith at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington, for his web page listing all the Ace Doubles he has information on; also to Steve Forty for some of the scans of books I don’t have. My collection is inadequate, and Steve had some I needed; and he volunteered to scan others. For those who are interested in high-quality looks at some wonderful American (and others) illustrations — including many F&SF covers and paintings — I urge you to visit Heritage Auctions‘ website. They sell millions of dollars worth of great original illustrations, and it is an inestimable resource for those who would like to see these works “up close and personal.” You don’t have to buy anything, but if you register you can inspect a lot of wonderful stuff.

If you feel the desire to comment on this week’s entry, please register, if you haven’t already — it’s free, and only takes a moment — or comment on my Facebook page or in the several groups where I publish a link. All your comments — good or bad — are welcome! Until next week, then!

Steve has been an active fan since the 1970s, when he founded the Palouse Empire Science Fiction Association and the more-or-less late MosCon in Pullman, WA and Moscow, ID, though he started reading SF/F in the early-to-mid 1950s, when he was just a sprat. He moved to Canada in 1985 and quickly became involved with Canadian cons, including ConText (’89 and ’81) and VCON. He’s published a couple of books and a number of short stories, and has collaborated with his two-time Aurora-winning wife Lynne Taylor Fahnestalk on a number of art projects. As of this writing he’s the proofreader for R. Graeme Cameron’s Polar Borealis and Polar Starlight publications. He’s been writing for Amazing Stories off and on since the early 1980s. His column can be found on Amazing Stories most Fridays.