You may think you know who played the original Dracula in the movies, but you might be wrong. I believe that most of you think of Bela Lugosi when you think of movie adaptations of Bram (Abraham) Stoker’s famous book, Dracula; but if so, you’d be mistaken. The first movie adaptation of Dracula was a total ripoff—a violation of copyright—by a German filmmaker, F(riedrich) W(ilhelm) Murnau, called (in an attempt to make it look like he didn’t steal the story) Nosferatu. (Contrary to popular opinion, the word “nosferatu” does not mean “vampire” or “undead”; the term originally might have come from the Greek “nosophoros.” “Nosophoros,” in the original Greek, stands for “plague carrier.” Because the vampire’s coffins in Nosferatu were full of rats as well as dirt, this makes some kind of sense. The word “Nosferatu” does appear in Stoker’s novel, but as a synonym for “undead.”)

According to one article, Stoker’s estate refused to sell the story for a movie adaptation and, since the film’s producer, Albin Grau, had created a movie company just for the purpose of telling a vampire story, Grau didn’t take rejection lying down.

Grau had been in Serbia in World War I and had become familiar with local vampire lore from talking to a farmer who claimed his own father was a vampire. Since he (Grau) was already an occultist (and a member of a cult called “Fraternitas Saturni” [Brotherhood of Saturn]), he created the movie company, Prana Film, to make occult movies (“Prana” is a Sanskrit word; see link). After being refused—possibly because Grau told Stoker’s widow, Florence, he was going to make an “expressionistic” movie—by Stoker’s estate. Remember that the early 1920s were, in artistic terms, partway between “Art Nouveau” (think Alphonse Mucha as an example) and “Art Deco” (think the top of the Empire State Building for an example); German Expressionism—in both art and film—was expanding, and might have been thought of by a traditionalist as an awful thing. So Florence refused Grau, and since he had already hired a director and screenwriter, Grau wasn’t going to let a little thing like copyright stand in his way. He had a few changes made to the script—changing the title and the main characters’ names, for example—and went ahead with the movie, hiring F.W. Murnau to direct.

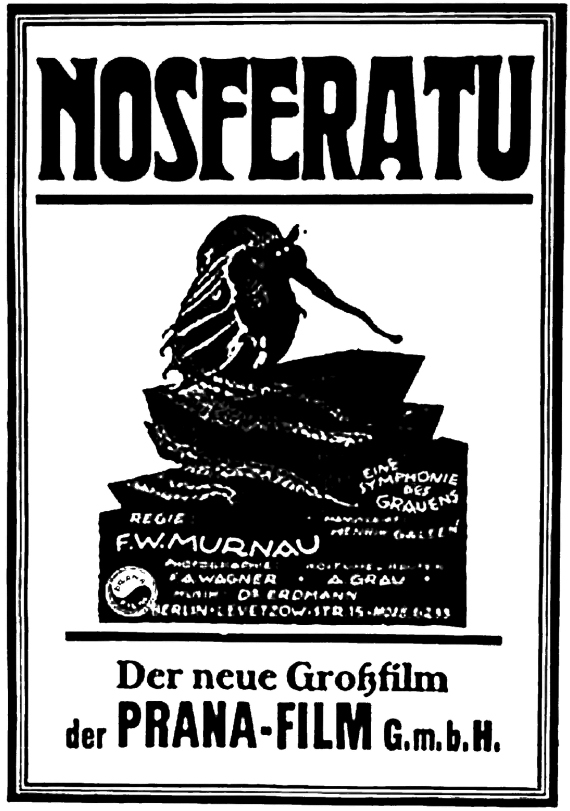

Since—at least in the English-language version I’ve seen—Count Orlok (Dracula’s new name for the Murnau Film) is indeed a plague-bringer—it appears that Grau, Murnau and the screenwriter (Henrik Galeen, already known for his work in The Golem) were all aware of the title’s Greek root. Nosferatu itself (See Figure 3) is subtitled “Eine Symphonie des Grauens” (A Symphony of Horror); since film’s earliest days, directors have been trying to bring us works of shock and/or horror, it appears, like the Edison Company’s Frankenstein, mentioned in last week’s column. And German expressionism was to bring us lots of what we would today call “classic” horror films, like The Golem (1915, starring Paul Wegener and Galeen himself, based on Jewish legend); l; The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920, perhaps Conrad Veidt’s best-known role); The Man Who Laughs (1928, based on a Victor Hugo story (according to the posters), starring Conrad Veidt and Mary Philbin) and many others.

I’ll assume for the moment, that you’re familiar with at least the movie Dracula’s characters, and I’ll go over the changes made by Galeen and Murnau (as I believe the director would have had input into the script as well) to the character names and, indeed, their characters. Rather than a blow-by-blow account of the movie which, by the way, is freely available on YouTube, I’ll just talk about various things in the film and my impressions thereof. Here are the characters you will encounter in Nosferatu

(Dracula characters, where they appear, in bold and parentheses):

Graf Orlok (Count Dracula) – Max Schreck

Thomas Hutter (Jonathan Harker) – Gustav von Wangenheim

Ellen Hutter (Mina Harker) – Greta Schröder

Harding, a boat owner (Hutter’s friend) – Georg H. Schnell

Ruth (Harding’s sister) – Ruth Landshoff

Professor Sievers (the town doctor) – Gustav Botz

Knock (an estate agent/Renfield) – Alexander Granach

Professor Bulwer, a Paracelsian doctor (Van Helsing) – John Gottowt

Even though some characters from the book appeared in the original German version of Nosferatu under their own names—which helped Stoker’s widow with her lawsuit—there are not analogs of every familiar character from the 1931 movie; one can see that Knock, for example, becomes the madman portrayed by Dwight Frye (Renfield) at about the time Dracula’s ship, the Empusa, docks in Wisborg—and Alexander Granach plays Knock with such vim and vigour that one can’t help but like the madman as he leads the hue and cry throughout the town, jumping on and off roofs, capering quite agilely despite his tonsure of white hair! There is no Van Helsing character, with perhaps the closest analog being Professor Bulwer, the “Paracelsian” doctor—a Paracelsian is one who believes as Paracelsus did, that man must live in harmony with nature and therefore studies “natural” cures rather than relying on old texts for inspiration.

The filmmakers hired Max Schreck (Figure 1), a stage actor for only his second-ever role in a movie, and I believe he did a very good job; his stilted acting was perfect for the character. His rat-like teeth and long claw-like fingernails emphasized the vampire as vermin. (I had always believed Schreck to be a stage name, because “Schreck” is German for fear, horror or shock (something in that area), but it appears it was, fittingly, the actor’s real name. (It appears the character played by Christopher Walken in Batman Returns–also named Max Shreck, spelled slightly differently—was named so in homage to this actor.) Schreck would go on to make a total of 19 films, dying in 1936 in Germany, which was then undergoing Nazification—a horror totally undreamed of in Murnau’s and Schreck’s day.) Although he put on a facade of normality for Hutter/Harker, Figure 2 shows him revealed to Hutter as Nosferatu.

Some things that interested me about the film were (in no particular order) that when Hutter first meets Professor Bulwer in the street, the professor tells him that there is no “running away from your fate.” Is there something the professor knows that we, or Hutton, don’t? Another thing: when Knock first receives Orlok’s letter enquiring about vacant houses in Wisborg (a fictitious town name, by the way), the letter is entirely in some kind of code, yet Knock has no trouble reading it and, indeed, seems to derive some sort of satisfaction from it as he reads to the end. Are Knock and Count Orlok linked in some sort of vampiric cult? The film, by the way, begins—in both German and English-language versions—with a title card that announces that it is an account of the “great death” that came to Wisborg in 1838, which to me leads back to the rats and plague. Surely the most determined of vampires can only kill a few people a night—whereas the rats would bring plague and quickly kill a larger number of victims.

Another interesting thing about the film is that in Dracula Harker is—although one of Dracula’s victims (or a victim of Dracula’s wives), not a stupid character—and the female characters are all victims; in this version, Hutter appears to be a medium-grade moron, a real doofus. (Not all that bright, for all that he manages to escape from Orlok’s castle and make his way back to Wisborg. Figure 4 shows Hutter looking in a mirror to discover twin “mosquito bites.” He laughs them off.) The real hero (heroine) here is Ellen, Hutter’s wife, who not only knows that the vampire is Orlok—she says she sees him in the window every night, since he bought the deserted house just across the street—but she also reads Hutter’s vampire book (that he acquired in Transylvania) and figures out how to kill him, doing so as an act of personal sacrifice.

Another thing I found extremely interesting in this movie was that although it was filmed in 1921, I’m guessing that in parts of rural Germany—and other parts of rural Europe as well—some of the costumes were probably still in use. Remember that World War I had only ended a few years earlier, and there were probably still parts of Europe that the war had scarcely touched. I noticed that there was a rider on the lead horse of the coach that took Hutter to Orlok’s castle, something you don’t see very much in movies; I’d like to know why.

Another interesting thing is that this movie is the reason that vampires in modern horror movies are killed by sunlight—most notably in Hammer films of the ‘sixties. In the original book, sunlight is a discomfort to vampires, but they can freely walk about in daylight (see also Bram Stoker’s Dracula); in this movie, possibly as another hedge against copyright infringement, Orlok is killed by direct sunlight, after Ellen keeps the vampire occupied until “cock’s crow.” Orlok also has the power of moving things with his mind—he puts the lid on a coffin he is occupying—and of walking through solid objects, as he brings his coffins to his new home in Wisborg without the formality of opening the door first. He also reflects quite well in the mirror next to Ellen’s bed. So a number of familiar vampire tropes either come from this movie or come from the original book and Dracula version (1931) despite this movie.

All in all, an interesting movie, and one to have fun with, contrasting with all the later versions of Stoker’s movie—and all the offspring of said movie, from Dracula’s Daughter (1936, Universal) to Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992, Francis Ford Coppola), to Dracula, Dead and Loving It (1995, Mel Brooks). Even with today’s emphasis on zombies, it’s clear the vampire movie isn’t going away any time soon! (By the way, Florence Stoker won her suit, and all European copies of the movie, script, etc., were destroyed. It was only because the book—and this movie—were in the public domain in the U.S. that any copies survived. Score one for piracy, though I don’t suggest that as a viable excuse.)

Don’t forget to drop me a comment on this week’s column. If you haven’t already registered—it’s free, and just takes a moment—you can register and leave a comment here. Or you can comment on my Facebook page, or in the several Facebook groups where I publish a link to this column. Don’t feel you have to agree with me to post a comment—corrections, differences of opinion, whatever; I’d love to hear from you. My opinion is, as always, my own, and doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of Amazing Stories or its owners, editors, publishers or other bloggers. See you next week!

Despite close to 100 years of films, Nosferatu is the one filmmakers have to look to when creating a vampire film. For all the innovations and explorations, Nosferatu remains the archetypal vampire film. Werner Herzog’s remake, while enjoyable, is just a remake.