Science fiction on film and television can occasionally do something that’s incredibly hard to pull off. It can appeal simultaneously and profoundly to the youngest audiences and to the most demanding adults.

This is something that has struck me while choosing SF to watch with my own children. There is plenty of SF and fantasy around that’s aimed squarely at kids, of course – but sometimes the genre can appeal across the generation in a way very few stories can.

One way SF can do this is simply to aim at children but to do so with sufficient freshness and charm that adults will be swept along. That would explain the appeal of many a 1950s genre movie, for example, or perhaps a TV show like Lost in Space. It would even go some way to accounting for the success of the original Star Wars. I’m all for that, but the stories I have in mind do something more.

When it is at its most impressive, SF in the mainstream media deals in ideas which are so bold and arresting that children and adults both respond to them.

Take the original Star Trek. Kids loved it, of course – and here in the UK, it became a staple of morning TV in the school holidays in the 1970s. Yet the reason it lasted three seasons in the US despite dwindling ratings was, reportedly, that NBC was impressed by the demographics of the show’s audience. It was being watched by smart, professional people whom advertisers regarded as valuable.

So, were the children just watching for the phasers and aliens, while the adults grappled with the ideas at play in the scripts? I don’t think so. From my own childhood memories of the show, I remember that what really distinguished one episode from another was an imaginative premise. My earliest memories of the show were of “that episode where the crew turned up in a Wild West town” or “the episode where they could alter time”. A strong puzzle, or a moral dilemma, would capture the interest of a child and an adult alike.

For me, this point was reinforced recently when I watched the early Star Trek episode ‘Charlie X’ with my sons. It’s about a juvenile being with god-like powers. I won’t claim the show is the most sophisticated or complex SF ever written, but I was struck by the way my kids ended up discussing the ethical dilemma which the Enterprise crew faced in deciding what to do with the troublesome alien.

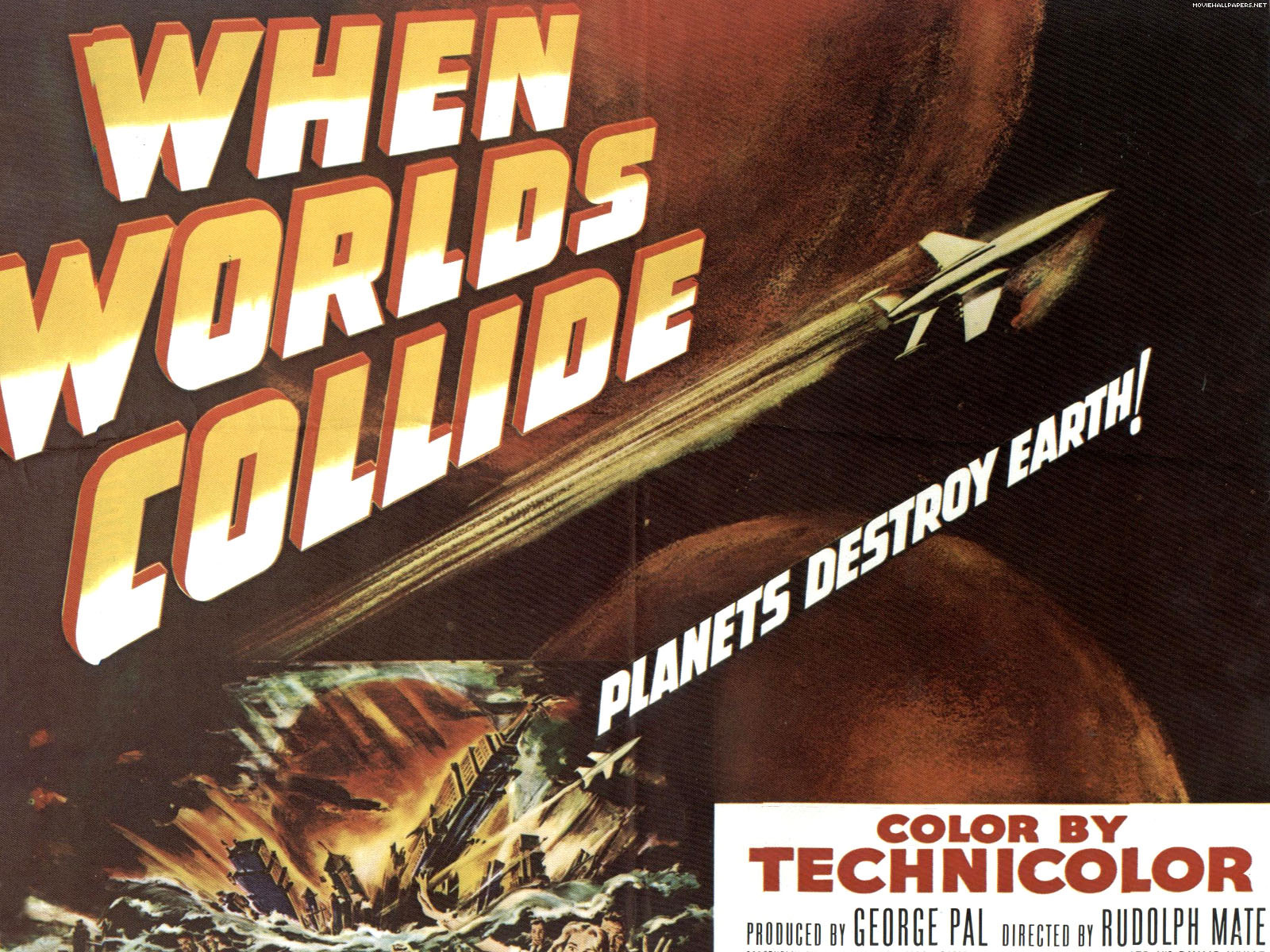

In fact, a lot of the SF that I saw as a child impressed me because it presented troubling moral questions. The George Pal production When Worlds Collide considered who should be saved if the Earth was facing destruction and only a lucky few could colonise another planet. The Planet of the Apes cycle terrified me with the prospect of nuclear apocalypse, but it also raised some weighty issues. Escape from the Planet of the Apes, for example, has two characters debate whether it would have been moral to kill Hitler when he was an innocent baby, or his mother before he was born.

But the more SF is written and produced, the more demanding the audience becomes. People who grew up on the genre demand to be intellectually satisfied at the same time as having their inner ten-year-old excited. And for me, it seems that no writers face quite such difficult demands on this front as the those working on Britain’s Doctor Who.

Conceived as a children’s show, Doctor Who has been running for half a century, if you overlook a lengthy gap in production, and was revived as peak time entertainment which needed to draw big audiences.

So, how do you write for a show that is expected to excite children, appeal to a mainstream audience and still satisfy the most unforgiving aficionado? For a long time, the revived show’s lead writer, Russell T Davies, got it right more often than not. Often his plots would rely on some pretty vague gobbledegook standing in for scientific theory, but most of the time those bold, generation-uniting ideas were there.

As the show went on, I felt the child audience won out. When we were introduced to a flying bus in the episode ‘Planet of the Dead’, you could sense the five-year-olds cheering while the high-minded genre fans rolled their eyes. Then came the tenure of Stephen Moffat, which I think has sometimes gone too far the other way. The show has tempted kids with bold promises of a planet full of the most deranged Daleks, or of all the Doctor’s scariest enemies uniting, only to let such simple but powerful notions get lost among some overly complex plotting.

But Doctor Who writers, like those on Star Trek, are given quite a challenge. They have to appeal to very young children and still satisfy a fan with a PhD, while respecting the continuity of a fifty-year-old show and avoiding any conflict with its massive ‘expanded universe’. All that on top of thinking up forty-five minutes of good story.

In the admittedly unlikely event that anyone were to commission me to write a Doctor Who, I imagine that brief would scare the words right out of me.