One of the more notorious aspects of the reputation of SF Fandom is our penchant for arguing over minutiae. The dreaded minutiae. Case in Point: BEM.

“What is a BEM?” you may well ask. This is where I snicker behind a knowing smile and smugly declare “Oh course you mean B.E.M.”

Frustrated, though not as yet motivated to punch me, you say:

“Fine. B.E.M. What’s a B.E.M.?”

“Bug Eyed Monster!” I reply, and much hilarity ensues, at least on my part.

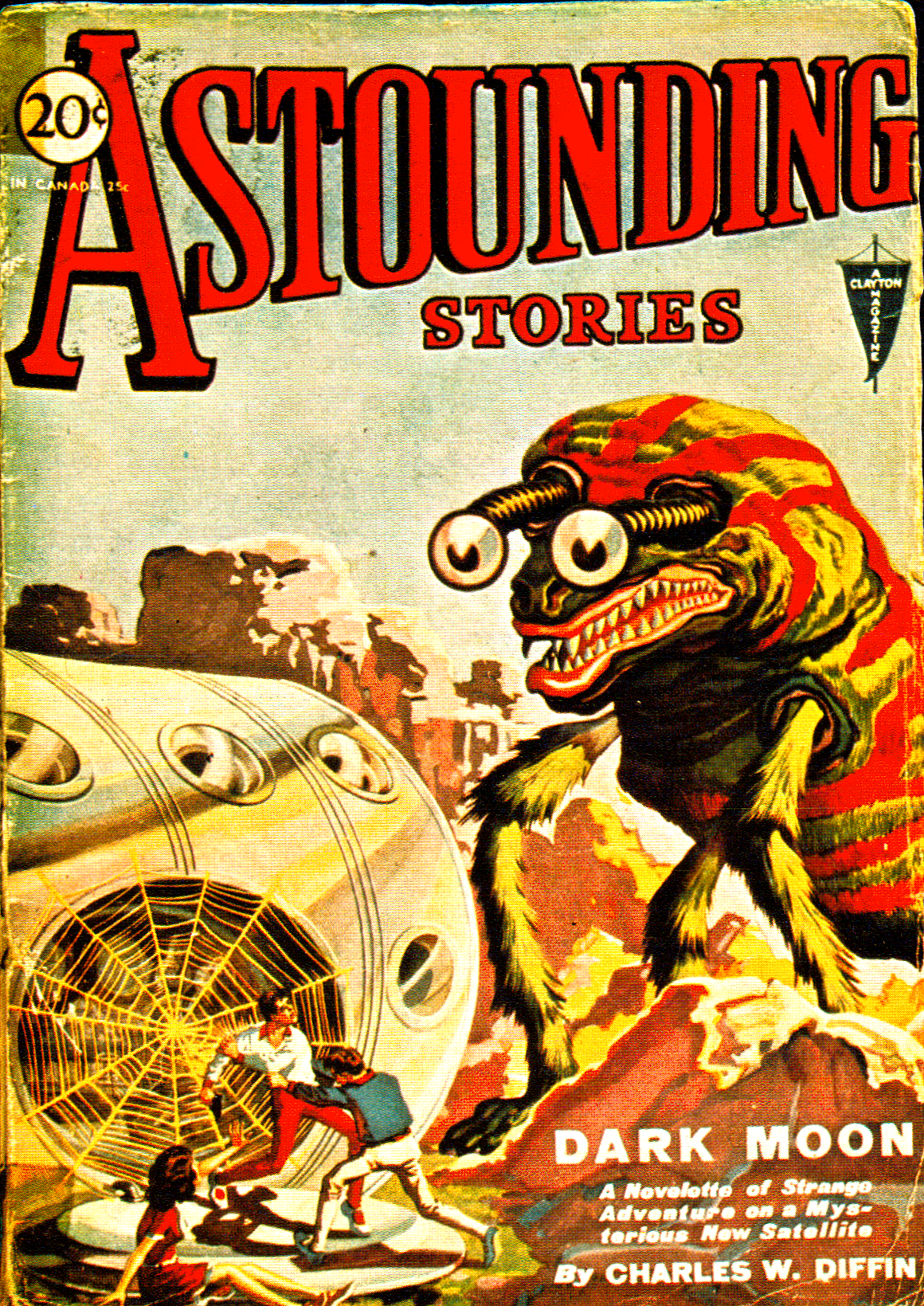

To anyone familiar with early SF pulp magazine covers the concept is taken for granted. Given that most SF monsters were humanoid, the easiest way to counteract any lingering hints of humanity was to grace the beasts with the compound eyes of insects; creatures noted for their lack of compassion. Or to employ giant eyes bugging out to convey predatory intent. Even better, place said eyes at the ends of stalks or tentacles. Such visions, along with brass bras and semi-naked heroines in distress, were so ubiquitous as to become instant clichés. No wonder someone came up with a handy-dandy quick acronym for quick reference.

Who? And when? These are the questions cult devotees of minutiae ask.

The term “Bug Eyed Monster” was first used by Michigan fan Martin Alger in August, 1939, when he announced the formation of “The Society For Prevention Of Bug Eyed Monsters On The Covers Of Science Fiction Publications.”

His first actual use of the acronym ‘BEM’ dates from a letter he wrote in 1941. According to Dick Eney, the author of Fancyclopedia II, it was the first strictly fannish slang to be included in a ‘mundane’ dictionary (some time prior to 1959) when Funk and Wagnall defined it as “various abhorrent monsters, such as are found in science-fiction.” Note that the term had already expanded in meaning to include any alien creature, monstrous in form, as used in SF art.

If you search long and hard among fan publications and websites you will find fen disputing the above information. I did, though I can’t remember where.

Or to pick another example, it is generally acknowledged by fen that Russ Chauvenet coined the term ‘Fanzine’ circa 1941. Prior to that time fanzines were called ‘Fanmags,’ or ‘FMZ.’ Recently I noted (in passing, soon forgotten) someone online attributing the term to someone else.

You might well take time out to sigh. Who cares? What’s the point of debating nit-picky minutiae? What’s the point of my even mentioning such?

Whereupon I jump up and down yelling:

“You’re missing the point!”

NOW you want to punch me.

Fantiquarians like myself, always interested in beginnings, love to track down the origins of things. Fortunately fen like me are few and rare, most fen preferring to live in the moment of their current passion, and at best we minutiae-minded are of occasional marginal interest and nothing more.

Whimsy. THAT’S my point. Never mind the history of acronyms, the USE of acronyms comes from the traditional fannish delight of playing with concepts, of having fun. Everything science fictional, indeed everything fannish, lends itself to parody, to word play, to almost Monty Pythonal silliness. Both fans and pros frequently contribute to the fun.

Here, in my columns for Amazing, I seek to promote the sheer, exuberant joy of fandom. And I can’t think of a better example of what I’m talking about than the hard cover anthology ‘SHAGGY B.E.M. STORIES’ edited by Mike Resnick and published by Nolocon Press in 1988 in time for Nolocon II, the World Science Fiction Convention held in New Orleans.

As Mike wrote in his introduction:

“I didn’t want to edit this book.”

“Really.”

“What I wanted to do was READ this book, and after waiting fifteen years for someone else to edit it, I realized that there was only one way it was ever going to see print, and that was if I did the work myself and then cajoled some weak-willed publisher into buying it.”

Thank Ghu he did. A finer anthology of science fiction parodies you won’t find anywhere.

Most of the stories are professional pieces by professional authors satirizing each other in professional magazines. But some are written by fans and appeared in fanzines. One of the best (before he became a pro) was written by Arthur C. Clarke in 1940. It is a Lovecraft Spoof, titled ‘AT THE MOUNTAINS OF MURKINESS.’

First, Clarke captures the mood of Lovecraftian writing very accurately:

“As we pressed onwards a vague malaise crept over every one of us. A feeling of uneasiness, of strange disquiet, began to make itself felt, apparently radiating from the very rocks and crags that lay buried beneath their immemorial covering of ice. It was such a sensation as one might have felt on entering a deserted building where some all-but-forgotten horror had long ago occurred.”

Then a hint of satiric exaggeration is introduced:

“…we crept out of the chamber, extinguishing our torches. The crevice McTwirp had scratched hastily in the solid rock, at the cost of two fingernails, was rather small for the four of us, but it was our only hope.”

Nevertheless the usual Lovecraftian amorphous, featureless, and indescribable creatures show up and turn out to be rather civilized chaps in their unalterably alien manner. The ‘Things’ are asked why they haven’t been discovered by the outside world before the current expedition. Their reply:

“We started writing stories about ourselves, and later we subsidized authors, particularly in America, to do the same. The result was that everyone read all about us in various magazines such as WEIRD TALES… and simply didn’t believe a word of it. So we were quite safe.”

A brilliant concept I say.

As for the ending, I won’t give anything away but to say it was very, very British.

Howard Waldrop contributes ‘CTHU’LABLANCA’ which describes the writings of Mortimer Morbius Moamrath, a lesser known rival of Lovecraft. I particularly enjoyed the following:

“Moamrath had written a series of stories with the prevailing idea that a race of elder beings (The Bad Old Ones) once controlled the Earth and solar system, but, through sheer stupidity and forgetfulness, got lost and wandered away. Meanwhile, another race of elder beings (The Good Old Ones) stumbled onto the Earth and decided it would do as well as anyplace. The Good Old Ones then had a billion year spree and picnic, and then all went to sleep. The Bad Old Ones continue to stumble around in a place beyond time and space (and, we might add, reason and logic.)”

Bill Wallace and Joe Pumilia provide further excerpts from ‘THE WORKS OF M. M. MOAMRATH,’ including some of his more famous closing lines:

“As I stared at the eldritch face leering down at me, I realized he was taller than I was!”

“Curse? What Curse?” he snorted, as the six-eyed demon flew down from the stars and ate him.”

“Invisible, eh? Well, we’ll see no more of him.”

“It’s not so bad finding a pile of spaghetti and jello on your living room floor…but when it calls you by name!…”

The anthology is more varied than the above suggests. Here are a few titles to indicate some of the famous SF works parodied in the anthology.

‘JOHN CARPER AND HIS ELECTRIC BARSOOM’ by Gene DeWeese and Robert Coulson.

‘THE 9 BILLION PUNS OF GOD’ by Ralph Roberts.

‘MAUREEN BIRNBAUM AT THE EARTH’S CORE’ by George Alec Effinger.

‘RIDERS OF THE PURPLE OOZE’ by M.M. Moamrath.

‘STAR SPATS’ by Jayge Carr.

And many more.

Take ‘NUTRIMANCER’ by Marc Laidlaw, for instance:

“Imagine a TV dinner, baked to a crisp. Silver foil peeled back by the heat of a toaster oven. Charred clots of chicken stew, succotash, nameless dessert, further blurred by a microfrost of recombinant mold like a diseased painter’s nightmare of verdigris.”

“Fungoid cityscape.”

“Metaphor stretched to the breaking point.”

“Lunch.”

But for the readers of AMAZING the pièce de résistance of the anthology has to be ‘MASTERS OF THE METROPOLIS’ by Randall Garett and Lin Carter (originally published in 1957).

This is a spoof of one of the underlying ‘symptoms’ of a typical ‘scientifiction’ story as published by Hugo Gernsback, the founder of AMAZING. A firm believer in scientific progress, he preferred tales that pointed out the advantages of technology-soon-to-come, tales in which the action took second place to detailed and evocative description of the technology meant to evoke the reader’s sense of wonder.

The story involves a modern (i.e. 1957) hero named ‘Sam IM4SF+’ (spoofing Gernsback’s fictional hero ‘Ralph I24C 41+’)* wandering the streets of New York city awash in awe at the science all around him:

“…he came to a turnstile, an artifact not unlike a rimless wheel, whose spokes revolved to allow his passage. He placed a coin in the mechanism, and the marvelous machine—but one of many mechanical marvels of the age—recorded his passage on a small dial and automatically added the value of his coin to the total theretofore accumulated. All this, mind, without a single human hand at the controls!”

And:

“…He strode past a theatre of the age which, instead of living actors, displayed amazing dramas recorded on strips of celluloid and projected by beams of light on tremendously white surfaces within the darkened theatre. Ingeniously recorded voices and sounds, cleverly synchronized to the movement of the figures on the screen, made them seem lifelike.”

“Ah, the wonders of modern science!” Sam marveled anew.”

The point is well made and hilarious. To be strictly fair, however, readers in the late 1920s reveled in detailed description of future technology, were inspired by it, and thoroughly understood the underlying theme that someday spectacular and miraculous technology as revealed in the pages of AMAZING, or something near like it, would in fact become commonplace, possibly within the lifetime of the readers. The whole point was that things would change, progress was inevitable, and someday, through technology, the world would be a better place. Thus Hugo Gernsback initiated the first major theme of science fiction: raw optimism and progress.

Later, in the 1930s, a time of worldwide depression and gathering war clouds, science fiction remained a beacon of hope seized upon by many a youthful imagination amid the expanding ranks of fandom. That science fiction eventually lost its naïve lustre is merely the result of changing times. Not Gernsback’s fault for raising the bar so high in the first place.

Taken out of context the articles and stories within AMAZING in the 1920s seem archaic, inaccurate, and downright silly. But put yourself in the context of the day, imagine yourself as a teenager back then, at a time when advancing technology was universally considered a good thing, and you’ll begin to understand the impact Gernsback’s vision had on countless minds. His legacy is with us still (if somewhat muted).

Yet the parody of his trademark technique is jolly all the same. The entire anthology is a jolly lark, well worth reading and chuckling over. Sheer delight from beginning to end.

How to get a copy? In my case I am grateful to Vancouver fan Howard Cherniack who years ago presented me with his copy knowing that I’d get (and continue to get) a tremendous kick out of it. Others may not be so lucky.

I suggest you haunt Ebay and Amazon. They be your best hope.

SHAGGY B.E.M. STORIES belongs on the shelf of everyone who loves and appreciates science fiction literature. It’s a classic.

(Editor’s Note: The name Ralph 124C41+ is meant to be pronounced and translates to: Ralph – One To For See For All, the ‘1+’ meaning all. Ralph is a super scientist of the future and was awarded the all important plus sign after his name to denote his genius and scientific contributions to society. And speaking of ancient science fiction – what the heck ever happened to making up futuristic and alien sounding names that included numbers and typographical symbols…?)

At the time “Masters of the Metropolis” was written,Sam Moskowitz had recently edited a magazine called “Science Fiction Plus” published by Gernsback and featuring Gernsbackian stories.The “Sam IM4SF+” character was to some extent a tweak at him.