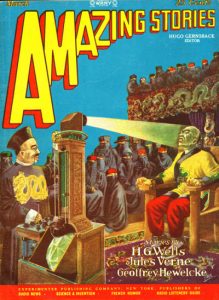

A man of East Asian descent sits bound to a chair. He recoils in pain as a beam of light shines on his face, emanating from a device that resembles some strange form of projection equipment. The machine is operated by another Asian man, whose face bears a malevolent grin. The surrounding room, decorated with images of Chinese dragons, is filled with observers whose faces are hidden as they watch the scene before them.

A man of East Asian descent sits bound to a chair. He recoils in pain as a beam of light shines on his face, emanating from a device that resembles some strange form of projection equipment. The machine is operated by another Asian man, whose face bears a malevolent grin. The surrounding room, decorated with images of Chinese dragons, is filled with observers whose faces are hidden as they watch the scene before them.

It was March 1928, and Amazing Stories was here again.

This month, Hugo Gernsback’s editorial discusses psychology:

There is little doubt that one of the most remarkable devices—as a matter of fact the most improbable device—that ever appeared on this planet, is the human brain in its capacity to think.

But, he goes on to argue, thinking and even reasoning can also be found within the animal kingdom. That dogs can be trained indicates a form of reasoning, says Gernsback, as does the building ability of ants (here, he cites Hans Heinz Ewers’ book The Ant People). The editorial makes the case that, while the behaviour of animals is largely instinctive and automatic, the same can be said of the behaviour of humans: “There are probably not six humans on the entire planet who do 80% of actual thinking and actual reasoning on new and untried paths during their working hours.”

Once again, though, we see something of a discrepancy between the subject matter of the editorial and that of the issue’s stories. The tales on offer this month are not concerned with blurring the line between human and animal – although one writer does, perhaps, blur the line between animal and plant. Instead, the contributors seem to have been looking more to the heavens, as their stories show a recurring interest in the Sun and Moon as objects of marvel, mystery and menace…

“Ten Million Miles Sunward” by Geoffrey Hewelcke

This story begins with the discovery of a new celestial body in 1933; this is initially taken to be a star, but the following year, it is identified as a comet. Then, in 1935, a newspaper man named Martin receives a frantic phone call from his acquaintance, astronomer Farintosh, who reports a terrible discovery: the comet is headed for Earth.

This story begins with the discovery of a new celestial body in 1933; this is initially taken to be a star, but the following year, it is identified as a comet. Then, in 1935, a newspaper man named Martin receives a frantic phone call from his acquaintance, astronomer Farintosh, who reports a terrible discovery: the comet is headed for Earth.

Farintosh’s colleagues in the astronomical community try to keep a lid on the story so as to avoid mass panic, but the news reaches the press despite this. A conference between scientists and politicians takes place to decide a course of action; one suggestion made is that the public be advised to commit suicide, thereby avoiding a slow death from the comet’s arrival. But then Farintosh arrives with a ray of hope: he proposes that the Earth can be saved – by altering its orbit so as to avoid the comet.

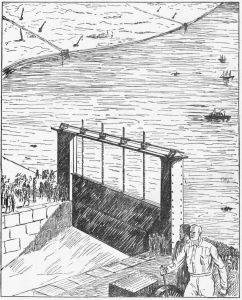

To do so, it would be necessary to displace a vast quantity of the planet’s matter – around thirty million million tons. Farintosh’s proposal is to achieve this by digging vast canals that will flood the Caspian Sea with water from the Black Sea. Although initially scornful, the delegates agree to put this plan into motion.

The leading engineers, astronomers and politicians hold a long-distance conference via radiotelevisionphone to discuss the vast undertaking. At the same time, the entire scheme receives harsh criticism from one Professor Schreiner, who argues that altering the orbit of the Earth will take it either too far from or too close to the Sun, thereby wiping out all life – and that if humanity is doomed to extinction either way, the last days of the species should not be wasted on such a futile undertaking.

The project is completed, and even Schreiner is impressed with the result. But Hadji Hassan Agha, a religious fanatic who believes that the impending destruction of the Earth is the will of God, decides to sabotage the canals. People involved with the canals start turning up dead, and eventually, the terrorist and his followers succeed in destroying the canals. This leads to a surge of what would now be termed Islamophobia, with violent mobs attacking Turkish embassies and “the beautiful Mohammedan mosque in the French capital”.

But the terrorism was not sufficient to halt the shifting of Earth’s orbit. The planet dips closer to the Sun, leading to global warming that kills vast numbers of people – all for the greater good, as the Earth successfully avoids the comet.

After recounting his experience of the atmospheric anomalies that arose from the comet’s passing, Martin describes the shape of the world after its near annihilation. It is now a warmer planet, with a shorter year, but humanity is adapting well to these changes – indeed, all armaments have been destroyed, and world peace rains beneath a global Supreme Council.

Another of Amazing’s periodic depictions of the apocalypse (the first Quarterly had recently published Earl L. Bell’s “The Moon of Doom”, to pick one example) “Ten Million Miles Sunward” ends with a puzzle.

“Now that you have read the story, you will want to know, of course, just what is wrong”, runs an editorial notice. “There are some exquisite bits of science involved in this story, but we are going to keep you guessing until next month, when the full solution will be printed. The solution, by the way, will be by no less an authority than Prof. W. J. Luyten, of the Harvard Observatory. Watch for it next month.”

Baron Münchhausen’s Scientific Adventures by Hugo Gernsback (Part 2 of 6)

Amazing continues reprinting Hugo Gernsback’s saga, again running two instalments from the original thirteen-part run in Electrical Experimenter.

Amazing continues reprinting Hugo Gernsback’s saga, again running two instalments from the original thirteen-part run in Electrical Experimenter.

“Münchhausen on the Moon” opens on a metafictional note as narrator I. M. Alier delivers some rather cutting comments relating to popular fiction, its authorship and its editorship; he goes on to relate a comical encounter with the irate Mayor of Yankton, before returning to his radio correspondence with the Moon-based Baron Münchhausen.

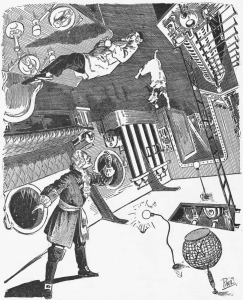

The good Baron discusses his journey to the Moon with his companion Professor Flitternix and a dog named Buster – the latter acting as a test subject outside of their craft, and revealing that the Moon has a breathable atmosphere. Their discoveries include species of luminescent fish and turtles, that reside within a cave and emit a strange green light; other animals exist on the Moon, but the Baron appears interested mainly in the edible varieties.

The next chapter, “The Earth as Viewed from the Moon”, opens with Alier reprinting a badly-written letter calling attention to perceived scientific inaccuracies in Münchhausen’s accounts (Gernsback is, perhaps, making a dig at his slower-witted readers here). After this, the Baron describes his view of Earth, reversing our familiar view of the Moon.

Gernsback’s tales of Baron Münchhausen are distinctly whimsical, but nonetheless show a firm interest in hard science, with the Baron reporting in detail on the discoveries he makes during his exploits:

Buster, who weighs some 10 lbs. on earth, weighs but 1½ lbs. on the moon. He found this out when he began to jump about. On earth he would not have jumped higher than about 4 feet. On the moon his 1½ lbs. carried him six times higher, for he expended as much muscular energy in his jump as he was accustomed to do on earth. Consequently, he went up about 24 feet into the air.

“Lakh-Dal, Destroyer of Souls” by W. J. Hammond

General Scott Humiston of the Intelligence Bureau in Washington asks Professor Fiske Errell, an eminent criminologist, a straightforward question: does he believe in evil spirits?

General Scott Humiston of the Intelligence Bureau in Washington asks Professor Fiske Errell, an eminent criminologist, a straightforward question: does he believe in evil spirits?

Errell reacts to this question with a degree of bewilderment. “Good God, man,” replies Humiston, “don’t you read the papers ? Haven’t you read of the crimewaves that are sweeping this country, the hold-ups, the gang wars, the murders and suicides? Don’t you realize that insanity is increasing among us at a frightful rate, that our asylums are already overcrowded and the whole land overrun with morons?”

Humiston goes on to claim that an Evil Mind, a Devil in human guise, is abroad in the world; an individual responsible for masterminding no less an atrocity than the First World War; a man referred to by those in the know as Lakh-Dal – Destroyer of Souls.

Although his personal history traces back to the Himalayas, this evildoer is now active in America, as evidenced by a pile of newspaper headlines produced by Humiston: “Stanford Professor Suffers Mental Collapse”; “San Francisco Editor Stricken with Aphasia”; “Noted Scientist Victim of Paresis”; “Senator Blank Has Nervous Breakdown”; “Vice Rampant in Hollywood.”

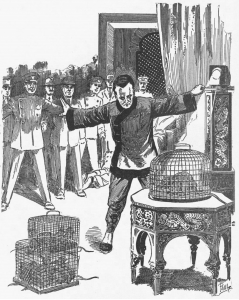

With the pair on Lakh-Dal’s trail, the criminal mastermind begins striking back in strange and eerie ways. At one point small lizards swarm into the office where the two men sit, and arrange themselves into letters, spelling out the message “Those Who Dare to Oppose Lakh-Dal, Die!” Later, General Humiston becomes a near-victim of Lakh-Dal’s death-ray.

Errell, it turns out, has a history of working undercover in Peking; through a change of clothes and a “yellow tint so carefully applied to his skin” he is able to pass as Chinese, and so prepares to do some detective work in New York’s Chinatown. He successfully reaches the lair of Lakh-Dal, and watches in horror as the mastermind uses a terrible invention to convert rays from the moon into a deadly weapon, causing a captive to first go insane and then rapidly decompose to a skeleton. “Lunar rays?” ponders Errell. “No, Lunacy rays! This Chinese devil has isolated the rays which cause dogs to bay at the moon—the rays which turn those of weak minds into imbeciles and cause those already insane to become raving maniacs!”

His disguise failing to fool Lukh-Dal, Errell gets captured by the villain, and is forced to witness a grotesque display of scientific ingenuity. Lukh-Dal uses a death-ray to reduce two rats to piles of ashes; then, using another ray, he proceeds to carry out a resurrection of sorts: “the handful of dirt began to quiver and squirm, to flop about from side to side, and finally to assume the flabby outlines of a new-born rat!” As the mastermind explains:

“It has been said that life is but a form of vibration. This little box, which in your ignorance you assumed to be a camera, is a machine for utilizing the Millikan, or Cosmic rays. These rays vibrate faster than any other rays known to science and consequently have the shortest wavelength, there being, in fact, 635,000,000,000,000 of them to the inch

“Buddha has said that man is made of dust. I go a step further and say ‘of dust and cocytin,’ which you saw me put together just now. With all the necessary ingredients present, it remained only to release the trigger of potentiality, which I did by means of the Cosmic ray.”

Lakh-Dal reveals that his scheme is to create rats to use as carriers of the bubonic plague. But Errell is able to thwart the villain with trickery of his own: using ventriloquism, he causes a voice to emanate seemingly from above, promising divine punishment for Lakh-Dal’s betrayal of Buddhism. The arch-villain loses his mind with fear, and shortly afterwards a Chinese woman – the husband of the man so gruesomely murdered – runs in with a sword to decapitate Lakh-Dal before committing suicide. The story concludes with Errell delivering a lecture on the scientific underpinnings of Lakh-Dal’s deadly inventions, complete with a diagram.

“Lakh-Dal, Destroyer of Souls” is a transparent imitation of Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu stories, with an added dose of Gernsbackian science fiction. Author W. J. Hammond does a good job of emulating his model – and, in the process, inevitably carries over the “yellow peril” racism of Rohmer’s series.

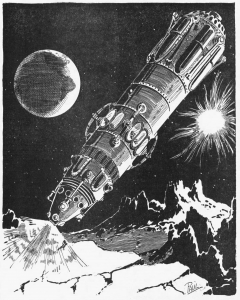

“Sub-Satellite” by Charles Cloukey

“Possibly the only practical space flyer that has come up for consideration so far, that is considered seriously by science, is the Goddard type of rocket flyer”, says this story’s editorial introduction. “This is based on sound scientific premises and sooner or later, one of these space flyers will come into being.”

“Possibly the only practical space flyer that has come up for consideration so far, that is considered seriously by science, is the Goddard type of rocket flyer”, says this story’s editorial introduction. “This is based on sound scientific premises and sooner or later, one of these space flyers will come into being.”

Narrator Kornfield returns to New York after a trip from Tibet, whereupon he learns that Dr. D. Francis Javis has successfully reached the Moon with the aid of Kornfield’s friend C. Jerry Clankey, who acted as chief radio engineer. Javis had previously invented a means of creating synthetic diamonds; after producing enough precious stones to fund his expedition, he destroyed his earlier invention and set to work on a rocket. Kornfield contrasts Javis’ craft with the cruder projectile described in Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon; unlike Verne’s vessel, Javis’ rocket possessed propellers to help it get off Earth, and could be steered by exploding its gaseous fuel at different points on its exterior.

However, in the process of making his great achievement, Javis made an enemy. R. Henri Duseau, an engineer, devised a pair of retractable wings for Javis’ rocket; but when Javis declined to take Duseau to the Moon with him – instead taking stunt flier Richard C. Brown – the embittered Duseau swore revenge on his former colleague. Javis also had to put up with negative publicity arising from being shot at by his drunkard son, Donald.

Clankey regales Kornfield with a full account of Javis and Brown’s lunar exploits, including their battles with stowaway Duseau – who, driven mad by hatred, tried to kill them (using poisoned bullets, no less). Accompanying this tale of lunar adventure is a more earthbound narrative: Javis made the mistake of willing the remaining money from his synthetic diamonds to his good-forr-nothing son Donald, rather than his banker son Jack, with the latter facing financial ruin to the heartbreak of his fiancée Jacqueline. But it all turns out well in the end, Duseau being hit by one of his own bullets (it travelled around the entirety of the Moon after being fired, becoming the sub-satellite of the title) and Javis making it back to Earth in time to sort out his son’s problems.

A solid runaround, with a few good science fiction ideas sprinkled in with the more conventional derring-do and meolodrama.

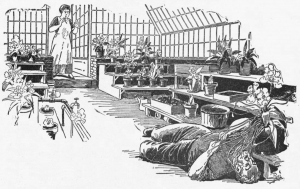

“The Flowering of the Strange Orchid” by H. G. Wells

Winter-Wedderburn, a lonely man who likes to grow orchids in his hothouse, buys some exotic specimens obtained by an explorer named Batten. His housekeeper is uncomfortable with the strange orchids he brings home, and is disturbed by the knowledge that Batten was found dead in a mangrove swamp, having been seemingly killed by leeches – and these orchids may well have been taken from his body.

Winter-Wedderburn, a lonely man who likes to grow orchids in his hothouse, buys some exotic specimens obtained by an explorer named Batten. His housekeeper is uncomfortable with the strange orchids he brings home, and is disturbed by the knowledge that Batten was found dead in a mangrove swamp, having been seemingly killed by leeches – and these orchids may well have been taken from his body.

Over time, one of the orchids – an unknown variety – begins to grow. The housekeeper remains disturbed: to her, the early buds resemble little white fingers poking through the dirt, while the lengthy rootlets that later emerge look to her like tentacles, and give her nightmares. She decides to stay away from the plant, and let Wedderburn admire it alone.

Wedderburn proceeds to do just that, up until the point where the strange orchid blossoms. When he fails to come in for tea, the housekeeper visits the hothouse and finds him lying on his back, the orchid’s rootlets sucking his blood like leeches.

Overcoming the narcotic effects of the plant’s scent, the housekeeper smashes the orchid with a flowerpot and drags Wedderburn to safety. He recovers, and is none the worse for his ordeal – indeed, the shy and reclusive Wedderburn ends the story in an uncharacteristically upbeat mood.

Like many of the H. G. Wells stories reprinted by Amazing, this 1894 tale shows a macabre streak. But it also shows the whimsical aspect of Wells’ work: Winter-Wedderburn is another charming short-form character study from the author.

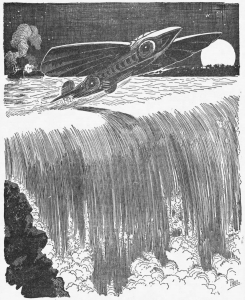

The Master of the World by Jules Verne (part 2 of 2)

Detective Strock and his comrades Wells, Walker and Hart continue their search for the Terror, the elusive vehicle apparently capable of acting as boat, submarine and car. They encounter the mysterious craft at the shores of Lake Erie and, after a shoot-out, Strock finds himself a captive on board the strange vehicle.

Detective Strock and his comrades Wells, Walker and Hart continue their search for the Terror, the elusive vehicle apparently capable of acting as boat, submarine and car. They encounter the mysterious craft at the shores of Lake Erie and, after a shoot-out, Strock finds himself a captive on board the strange vehicle.

Strock confronts the captain, who reveals himself to be the notorious Robur the Conqueror whose past exploits were covered in the novel of the same name, and are known to the detective. Robur is known for his ingenious aircraft, and sure enough, the Terror turns out to have a forth mode, one capable of flight.

Robur, apparently consumed with megalomania, flies the Terror directly into a storm; the craft is hit by lightning and destroyed. Strock awakes to find himself on a steamer at the Gulf of Mexico; but there is no sign of Robur or his henchmen, who are presumably dead.

And so ends the final Jules Verne novel to be published in Amazing under the editorship of Hugo Gernsback.

Discussions

This month’s letters column is the usual mixture of the positive, as when 9-year-old Herman G. Gelfend mentions having drawn upon Ray Cummings’ “Around the Universe” for a school project about the Moon; and the negative, as when Victor Lewis admits to finding some of the magazine’s stories too macabre:

You published one story about the man that entered the subterranean world in Alaska, and was captured by Gold Bug Spirits; and made prisoner at their altar; that gave me the horrors. What on earth did you ever publish such a story as that for? We read stories to be amused; not to get something to give us the creeps. I like most everything Mr. H. G. Wells writes, but must disapprove of The Stolen Body—that is another story that gave me the creeps.

“Do you not know that many people crave stories of the description which you complain gave you the horrors?” asks the editorial reply. “Then again, do you not think you are over-sensitive in being so affected by fiction?”

Continuing the ongoing dispute over H. G. Wells, reader L. G. Townsend weighs in by accusing the magazine of using Wells’ reputation alone as a selling point rather than the merit of his fiction (“I simply do not care for blind hero worship. I believe in judging a man by the goods he delivers”)

H. B. Hargrove lists his favourite and least favourite stories, including in the latter camp most of H. G. Wells’ tales (“In my opinion. Wells’ stories are not worth the valuable space they occupy in your magazine”) along with A. Hyatt Verrill’s “The Astounding Discoveries of Doctor Mentiroso” (“I cannot understand how the Doctor’s machine can take him into the past by racing against the earth’s rotation. The fourth dimension is too much for my feeble brain anyway”) before concluding with “a plea for more illustrations and fewer stories by H. G. Wells”). The editorial response defends Wells, albeit with a minor concession: “he sometimes seems to be too sure of himself. This very often seems to us to be a characteristic failing of the English.”

David Ireland discusses the logistics of The War of the Worlds, comparing the projectile cylinders that the Martians use for space travel with armaments available during World War I. Other comments in his letter include digs at the magazine’s detective fiction: “I don’t care for the scientific detective stories, which appear in Amazing Stories so frequently. That type of story can be found behind the covers of a ‘dime novel,’ and has no place in Amazing Stories.”

Ralph L. Myers makes a relatively mild jab at Wells: “H. G. Wells does not match up to my ideas of a story writer, but, then, he has his style, and I can either read him or pass him up.” William Guerin, meanwhile, comes out in support of Wells:

Ever since Discussions Department started I have studied the letters submitted and have finally concluded that the stories are read by those who delight in fairy-tales injected with a little sweetening of so-called science, and by children. I must, of course, place myself in one of these classes; being 17, I choose the former. H. G. Wells is not enjoyed by your readers because he does not write fairy-tales. His stories are realistic, accurate and quaint and have a certain originality about them. “The Colour Out of Space” which I do not know who wrote was, to me, the best story printed in Amazing Stories.

On a more negative note, Guerin says that Jules Verne’s Robur the Conqueror “belongs more in ‘Boy’s Life’ or ‘Travel'” while A. Merritt’s The Moon Pool is “about the worst nonsense printed in Amazing Stories, belonging more in your French Humor or something else”. However, he concludes, “Except for Mr. Merritt’s brain-storm-gone-wrong and Mr. Burroughs’ drivel, yours is the best magazine on the market.”

Another teenager, 19-year-old Maurice C. Volkman, offers a mixed assessment of Wells:

His stories are quite entertaining, which is all that is required. If anyone stops to analyze them, they are—terrible. His “War of the Worlds” could be made into a fine tale, but he has ruined an otherwise good subject, it is entertaining, but what —no words can express my disgust. He has pictured man as a stupid ignoramus. If such a thing ever fell on the earth an army would immediately be thrown around it. Scientists from all over the world would come to investigate. The Martians would not be given a chance to build their War Machines, let alone use them.

Also under fire in this letter is Bob Olsen: “I have just read a small book on Einstein, and it seems to me that whoever wrote ‘The Four Dimensional Roller Press‘ did not have a very clear idea of what the fourth dimension is.” On a related note, the fourth dimension is a topic that throws reader Salvador A. Papason: “How do they know that there is a fourth dimension if they are not sure what it is?”

15-year-old chemistry student F. Schuyler Miller – who would later write fiction for Amazing and other magazines – expresses scepticism towards the science in Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Martian adventures, but acknowledges that George Paul Bauer’s “Beyond the Infra Red” opened his mind in this respect: perhaps, he argues, Burroughs’ Martians exist beyond the visible spectrum, like the people in Bauer’s story. He also offers an insight into how Amazing might have been received by contemporary family units:

As to old-fashioned parents who object to Amazing Stories, I can only deplore their prejudices. Mine are not that way, in fact my father started me on Verne when I was yet comparatively young. From Verne, I picked up Wells, and then turned my attention to the magazine world, welcoming the arrival of Amazing Stories. True, he has not read the magazine, but that, I am sure, is largely due to a lack of time and a dislike for the magazine form of fiction in general. In addition, I can cite the case of a boy to whom I lent my first seven copies. He kept them for nearly a year, but he buys the magazine himself now. His father confiscated the magazines as soon as they appeared in the house, but not for purposes of censure. My friend was not able to read the issues until his father had first perused them, often more than once.

G. P. Simeon defends H. G. Wells from detractors (“Perhaps there is something to this fourth dimension stuff after all. Their criticism must be based on some thing that has no solidity in the world we know”) and briefly praises a few stories by other authors, but dismisses the magazine’s detective stories, criticises Garret Smith’s Treasures of Tantalus (“Anyone having at his command the wonderful inventions of Professor Fleckner would certainly not go to such a lot of trouble to get hold of treasures which would be dwarfed by the value of the patent rights to the telephonoscope alone”) and derides the science in A. Merritt’s stories (“Sounds so much like the ‘electric belts’ or ‘magnetic inner soles’ that they still sell to the yokels”).

Alvin Moore praises Treasures of Tantalus, expressing surprise that it was not better-received by readers (the editorial reply presents this as evidence that detective stories have a place in Amazing after all) before weighing in on the Mentiroso story: “It strikes me that the story is a remarkably clear sugar-coated exposition of Einstein’s theory”, he says. “Let the readers think and grumble—it will do them good.”

W. Pillino is another reader who speaks approvingly of the controversial “Dr. Mentiroso” (“I should think that Mr. A. Hyatt Verrill knows far more than the average well informed person could ever wish to know about the fourth dimension”) and “Beyond the Infra-Red” (“I think that vibrations will play a very important part in the lives of the people a hundred years from now”).

In an unusual missive, T. A. Netland introduces moral philosophy to the letters column:

Regarding the magazine, I have just one criticism to make. Nearly all Scientiiction writers apply the Law of Selfishness, the struggle for existence, and the survival of the fittest to the highest evolutionary types, when—as a matter of fact—it should only govern the lower kingdoms of Nature.

The Social qualities; unselfishness; co-operation, self-sacrifice and service are characteristic of the most highly evolved types, and that is mostly lost sight of by your writers. In depicting future conditions on our planet, or older evolutions on other planets, scientifiction writers might well use some of the highest evolutionary ideals taught and exemplified by such flowers of our Humanity as Vyasa, Tahuti, Zoroaster, Orpheus, Buddha, Jesus, Sri Krishna, Confucius, Lao Tze, etc.

The letter goes on to request stories exploring the science of sleep (“Why are food and rest not sufficient for the bodily functions? Why is the UNCONSCIOUSNESS of sleep necessary?”) before contemplating the existence of “states of matter just as well suitable for expression of consciousness as our own” but “finer… than the ether”.

Another reader, Johnnie Walker, also waxes philosophical – specifically, about time travel:

If some one from our future were to return to us now, and exhibit himself, I should be very much disappointed with my Maker. Because that would show me that I was, according to destiny, pre-ordained to do just a certain thing and nothing else. If I knew that I were to become a great man—or a failure—regardless of what I tried to do (or did) I would lose all ambition and merely sit back and wait for what is going to happen.

George L. Reed defends the magazine’s stories from charges of scientific inaccuracy:

For the one highbrow professor who takes seven pages to kick about the impossible imaginations of the scientific writer, and wakes up to find out that he doesn’t even know his history, there are thousands of us ignorant fellows, who glory in the versatile imagination of your clever writers. They all are good. Every story contains something of value and is very highly entertaining. Let the professor read his technical library for his precise line of reasoning, I for one shout: Long live the Amazing Stories!

A number of past letters had discussed the proposition of a new science club. George A. Wines joins in, describing an extant group, the American Order of Science (A. O. O. S.) which he first organised in 1914: “It is a secret order, has a constitution, set of bylaws, a binding oath, secret code for writing formulae [sic], pass words and signs.” Amongst the inventions produced by the group was “an electric gun that was a real success, turned over to the government when war broke out.” He suggests that the group could be expanded to include laboratories elsewhere in the US. The editorial response objects to the secretive nature of this group: “As far as possible, we think that what we know should be disclosed wherever it will benefit humanity.”

Jack Darrow praises his favourite stories and asks for sequels to “The Tide Projectile Transportation Co.” by Will H. Gray and “The Face in the Abyss” by A. Merritt. This latter story also comes up in the issue’s final letter, from a reader with the retrospectively amusing name of H. Potter:

I want to tell you of the strange effect the story of the “Face in the Abyss” had on me. This is also answering your request asking what we think about it. The story at the first reading was not very interesting to me; but the final roundup was so strange in comparison to the other stories that at each succeeding reading it seemed to me the characters in the story actually lived and that I was a member of the part, a silent witness, watching all these happenings.

The girl Suarri, and her affection for Graydon are very cleverly introduced and woven into the story, and the winged serpents visible only in the one certain light is so intricately interlaced and described that I had a feeling as if I wanted to be there in person myself.

And when Graydon and his companions were shown “The Face” and Graydon was the only one able to withstand the “Call” to come on over, even though it was with help of the Snake Mother, his subsequent exile to the border of this strange land and “told to move on” and his return and attack, sickness—return to civilization and final return to Ya-Atlanchi, are incidents that to me seem to be a chapter torn from some history of long ago and appear to be very much closer to my ego than just a soulless story in a magazine.

I hope I have conveyed my meaning to you in the right light, and I am eagerly awaiting the sequel to this first instalment.

Recent Comments