Ahh, the launch of a new series is always fraught with equal measures of trepidation and anticipation, fear and excitement. This one perhaps more so than most as both the subject and the object of this series are near and dear to me.

I now propose to engage in a series of individual analysis and critique of the stories collected in the 1970 anthology THE SCIENCE FICTION HALL OF FAME, VOLUME ONE, edited by Robert Silverberg (who the field is forever indebted to for organizing this anthology and for having the fortitude to trust his own judgement and select about half the contents on his own say so).

It used to be that reading this volume was a right of passage for any serious fan of science fiction, a passport of recognition. Whether you liked the stories or not, if you’d worked your way through these 26 tales, you were widely familiar with the field; one could do worse by restricting oneself to the works of the included (not that I am suggesting that). If you’d read it through, you were a fan; you could speak in a somewhat informed fashion about the history of the field, you were familiar with most of the primary themes and the various manners in which different authors engaged with them.

It used to be that reading this volume was a right of passage for any serious fan of science fiction, a passport of recognition. Whether you liked the stories or not, if you’d worked your way through these 26 tales, you were widely familiar with the field; one could do worse by restricting oneself to the works of the included (not that I am suggesting that). If you’d read it through, you were a fan; you could speak in a somewhat informed fashion about the history of the field, you were familiar with most of the primary themes and the various manners in which different authors engaged with them.

Were I teaching a class on the evolution of the short science fiction story, I would include this anthology in the curriculum, along with Asimov’s Before the Golden Age, the Hugo Winners, Dangerous Visions and one (or several) running series, perhaps Merril’s or Wollheim & Carrs’.

None of those other works however can come close to the archaeological slice that Hall of Fame cuts through the layers of stratification and none so brilliantly reveals that our SFnal Troy is not one city but many, each new layer built upon the remains of a previous civilization, while still retaining a kind of percolation, allowing for bits and pieces of antediluvian process to permeate upwards. Like discovering the installation of an eight track player in a modern electric car

I’ve taken on this retro-read for two discrete purposes. The first engendered by my belief that there are redeeming qualities still to be found in these older works and that it is important and necessary that we retain a connection to the history of our genre (perhaps more so for practitioners than consumers).

I’ve taken on this retro-read for two discrete purposes. The first engendered by my belief that there are redeeming qualities still to be found in these older works and that it is important and necessary that we retain a connection to the history of our genre (perhaps more so for practitioners than consumers).

The second is to (try) and identify those things within each of these stories that may make them unappealing to a contemporary audience and, while doing so, hopefully offering up some insight that may make (some of) these works a bit more palatable and accessible.

My challenge is of course to try and approach these readings with a fresh eye (nearly impossible as I’ve worn out two copies of the anthology and my current one is threatening to fall apart: I have indeed read this anthology from cover to cover innumerable times.) Where I fail to do so, it most likely will be a case of omission rather than commission – failing to recognize a technological or societal disconnect that might be glaring to a younger reader. My only real excuse is that my formative years were infused with literature of this nature. We all try to learn and adapt and change for the better but like most, I am a product of my time.

Fortunately, I’m pretty sure that correction will not be long in coming if I do stumble. And that’s fine and expected, part of this process of hanging oneself out there. On the other hand, I do hope that most will read this series in the spirit in which it is intended, an exploration that we can all share and hopefully learn something from.

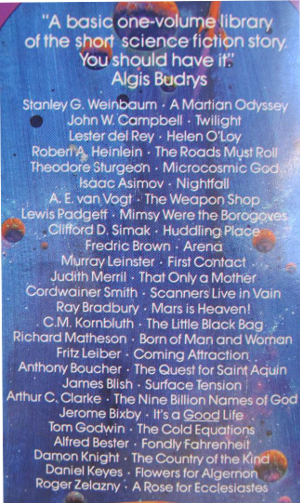

THE SCIENCE FICTION HALL OF FAME, edited by Robert Silverberg

Table of Contents:

- · Introduction · Robert Silverberg

- · A Martian Odyssey · Stanley G. Weinbaum

- · Twilight · John W. Campbell, Jr.

- · Helen O’Loy · Lester del Rey ·

- · The Roads Must Roll · Robert A. Heinlein

- · Microcosmic God · Theodore Sturgeon

- · Nightfall · Isaac Asimov

- · The Weapon Shop · A. E. van Vogt

- · Mimsy Were the Borogoves · Lewis Padgett

- · Huddling Place · Clifford D. Simak

- · Arena · Fredric Brown

- · First Contact · Murray Leinster

- · That Only a Mother · Judith Merril

- · Scanners Live in Vain · Cordwainer Smith

- · Mars Is Heaven! · Ray Bradbury

- · The Little Black Bag · C. M. Kornbluth

- · Born of Man and Woman · Richard Matheson

- · Coming Attraction · Fritz Leiber

- · The Quest for Saint Aquin · Anthony Boucher

- · Surface Tension · James Blish

- · The Nine Billion Names of God · Arthur C. Clarke

- · It’s a Good Life · Jerome Bixby

- · The Cold Equations · Tom Godwin

- · Fondly Fahrenheit · Alfred Bester

- · The Country of the Kind · Damon Knight

- · Flowers for Algernon · Daniel Keyes

- · A Rose for Ecclesiastes · Roger Zelazny

Just looking at the names included is like looking at SF’s own Hollywood Walk of Fame. It includes stories by the Olympians of SF – Asimov, Bradbury and Clarke and a host of other names to conjure with – Sturgeon, Matheson, Zelazny, Knight, Brown, Smith…two of SF’s leading female authors – Merril and C. L. Moore (though Brackett is disturbingly absent) and several names that have largely been forgotten these days – Bixby, Godwin, Leiber, Leinster….

Like I said, if you were doing a survey of SF pre-1965, you’d do yourself a pretty good turn by reading just these authors.

The origin story for this seminal volume is pretty straight forward: SFWA, the non-profit writers organization representing science fiction and fantasy authors, began offering their annual award, the NEBULA, in 1966 (for works published in 1965). This was done to help solidify the organization and in emulation of other writers guilds.

The members of SFWA, being an historically-minded lot (and cognizant of their position standing atop the shoulders of giants) decided to honor those works that had come before the institution of the Nebula. Robert Silverberg, being SFWA’s President at the time (’67-68 and the second so elected) was the natural choice to head up the editing process.

The members of SFWA were polled (each, if memory serves, being allowed to nominate ten works); Mr. Silverberg decided that individual authors should have only a single representation in the collection which knocked out a lot of the suggestions. The end result was 15 stories voted on by what was then arguably the pantheon of science fiction and fantasy writing. Robert then selected the remaining 11 stories based on his own knowledge and experience. He wasn’t a bad choice to rely on in this regard – he’d been a fan since at least 1949 when he simultaneously published Starship, a fanzine, and made his first sale (non-fiction). He sold his first novel in 1955 (a juvenile), was the youngest author to receive the ‘most promising new talent’ nod and went on to become one of the most prolific authors of the 1950s, largely pulp works and many written under magazine house names. He had a personal epiphany in 1959, realizing that he was concentrating on sales rather than writing, and withdrew from the field until Frederik Pohl pulled him back in. You can Google ‘Bob’ to find out the results.

The SFWA poll numbers ended up selecting Asimov’s Nightfall as the top story, followed by Weinbaum’s A Martian Odyssey and Keyes’ Flowers For Algernon.

The stories collected in SFHOFV1 were originally published between 1934 and 1963. One should note that the publishing environment for science fiction, fantasy and horror was much different from today; the market was restricted to the pulp magazines for much of that period. It wasn’t until 1943 that the first anthology was published by a traditional publishing house (specialty press editions of various works were being produced by fans). Ace Books wouldn’t begin publishing SF in paperback until 1953 (and even then most of the “novels” originally published were drawn from stories that had been published in the magazines, resulting in novels that were drawn from serialized stories, expanded shorter pieces or ‘fix-ups’). Shorter lengths dominated the field – which makes the selection of these 26 stories all that much more impressive.

Here is a break-down of the selections by decade of original publication:

1930s – 3

1940s – 10

1950s – 12

1960s – 1

(It should probably be noted that that the bell-curve suggested above largely reflects the size of the field as well, with the 1950s having been a boom period. No surprise that the majority of the works hail from that decade – magazines and authors were “popping from ze voodvork out”*. The scope of the selections is self-limiting so far as the 1960s are concerned.)

The vast majority of the stories included were originally published in the professional markets of their day – the pulps.. One – by Cordwainer Smith – being published in a semi-professional magazine. Here is a break down of the sources:

Astounding Science Fiction, John W. Campbell Jr, editor – 13

Fantasy & Science Fiction, Anthony Boucher & Philip J. McComas; Anthony Boucher; Robert P. Mills; and Avram Davidson, editors – 5

Fantasy Book, William & Margaret Crawford (as ‘Garret Ford’) editor – 1

Galaxy, Horace L. Gold, editor – 2

New Tales of Space and Time, Raymond J. Healy editor – 1

Planet Stories, Paul Lawrence Payne editor – 1

Star Science Fiction, Frederik Pohl editor – 2

Wonder Stories, Charles D. Hornig editor – 1

(Fantasy Book is the semi-professional magazine. Frederik Pohl routinely read the semi-pro and amateur publications of the day in pursuit of discovering new talent. Had he not, we might never have experienced the joy and wonder of the works of Cordwainer Smith.)

One can clearly see JW Campbell’s influence at work.

If I were to be asked which of the stories in this anthology are my favorites, and I could pick only five, that list would include A Martian Odyssey. It would also include Microcosmic God – Sturgeon, Mimsy Were the Borogoves – Padgett, First Contact – Leinster and Surface Tension – Blish. Though that listing is likely to change if I were to offer it at another time.

Of the 27 authors represented, only two are women – Judith Merril and C. L. Moore, Moore writing in collaboration with her husband Henry Kuttner under the Lewis Padgett pseudonym. (Perhaps the most successful writing team of their generation and quite capable and worthy individually, with, I think, Catherine beating out Henry by a not inconsiderable margin.)

A quick perusal of one of the many pieces of biographical information available on the web will reveal that 25 of the authors appear to be exclusively both white and male. Gender identity, sexual orientation, religious affiliation, belief systems are guessable but not certain without an amount of research not warranted by the limited scope of this piece. Suffice to say that this particular collection of authors is pretty representative of the field of its day, in so far as the professional pulp market is concerned.

The lack of inclusion should not be all that surprising. The sources from which these stories were drawn were not known to deliberately attempt to service any market other than the “mainstream”, which between 1934 and 1963 was largely a monolithic, white, anglo-saxo-phone one (with the occasional female and Jew making an appearance. It was not uncommon during this era for authors with names that were associated with minorities to adopt pseudonyms – and for editors to suggest that they do so.)

This is historical context. Absent time machines, we are unable to change history (and even then…). Noting and recognizing the lack of diversity and the ways in which this has shaped the genre to date are, I think, the instructive aspects here. I do think it appropriate to note these differences from earlier days and would suggest that any introduction of this volume be accompanied by a note to the effect that the genre has changed dramatically since 1970 and, happily, continues to evolve.

The other contextual factor to consider is that of the society and technology of the times. We begin with the 1930s and just a few highlights to set the scene and tone:

1934 saw the first regular transatlantic air mail service (Germany to Brazil); four radio broadcasting networks were operating in the US. The first US aircraft carrier was commissioned; an intravenous anesthetic was used on a human for the first time; the first cathode ray tube television sets were manufactured in Germany; the Hammond organ was patented; Flash Gordon debuted in comics; the Apollo Theater in Harlem opened; It Happened One Night opened in theaters; the Three Stooges debut; Hitler consolidates power.

More significantly to science fiction, it would be ten more years before a man made rocket achieved space altitude (189 kilometers). It would be 8 more years before penicillin was widely used; Einstein had been awarded the Nobel Prize only 13 years previously. Percival Lowell’s description of Mars largely prevailed (it would not be officially discredited until the 1960s) and the United States, if not most of the rest of the developed world, was in the grip of technology fever; US women had only been voting for 14 years, Africa was dominated by colonial powers (as was the Middle East and portions of Asia); in recovery from the Great Depression, US wage laws still allowed for discriminatory pay rates and, particularly in the south, minorities were still largely disenfranchised.

No television. No trans-oceanic airliners. No cell phones. No solid knowledge of what was beyond the atmosphere. No antibiotics. No transplant operations. No space telescopes. No computers – of any kind, unless you count the abacus or sliderule. No velcro. No teflon. No nylon (all stockings were silk, ooooo.) No polyethylene. No MacDonalds. No KFC.

It is out of this milieu that Stanley Grauman Weinbaum rose to dominate the field with the publication of a single short story A Martian Odyssey. Sadly, his promise would not be fulfilled as he would die within a year of the story’s publication.

He did, however, manage to write a fair number of shorts prior to his death (several of which were published posthumously) and a few novels. His stories covered many of the seminal themes of the field – first contact, superior evolution, genetic engineering, dopplegangers. A Martian Odyssey would go on to become one of the most anthologized shorts in the history of the field.

It is with A Martian Odyssey that Weinbaum made what are perhaps his two greatest contributions to the field: aliens that are equal to but different from humans (anticipating Campbell’s call for “a creature who thinks as well as a man, or better than a man, but not like a man”) and introducing early aspects of comprehensive world-building, creating fully-realized alien worlds that aren’t transplanted Earth analogues.

*Freely borrowed from the Reginald Bretnor tale The Gnurrs Come From the Voodvork Out.

Next: Part 2: A Martian Odyssey by Stanley G. Weinbaum

Actually, this sounds like a delicious series. Many of the writers listed I’ve already reviewed, (or are on my list to do) because I believe that rereadability is the truest mark of excellence.

I’d just like to mention in passing that Gardner Dozois, who’s edited the Year’s Best Science Fiction, is one of my favorite reads for recapping a year’s current writing and will magically transform any SF novice into a middling expert by simply rereading his year summation.

There’s much to be gained in rereading the greatest SF stories, something that Micheal Moorcock has done to great effect. I love indulging in SF’s metanarrative.