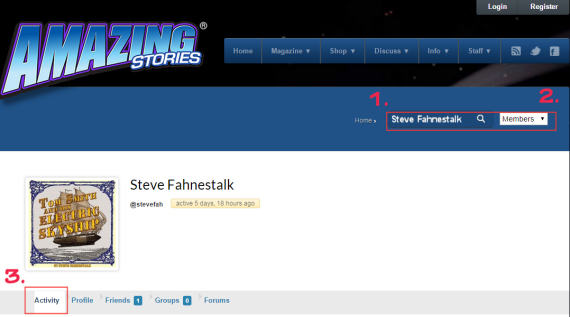

If you were reading SF/F in 1969, you probably recognize the beginning of my title as an homage to Isaac Asimov’s 100th book, which came out that year. This is my 100th consecutive weekly column, and I’m kinda proud of it—I can’t say I’ve done anything that consistent before in my life (except, you know, school and so on). And no, I’m not comparing myself to Asimov; this is in no way comparable to writing 100 books! Anyway, for this one, I thought about putting links in to every one of the previous columns, but I decided that would be an excruciatingly long list. Instead, I invite you to look at Figure 2 and do the following steps: 1-type my name in the search box; 2-make sure it’s set for “Members” and search; 3-go to the “Activity” tab. You’ll see a list of all my columns in reverse order; i.e., the newest first. (Ed’s note: or, you could go to the Staff page, click on Steve’s picture and click on the button that says “Read Steve’s Posts”. Or just click here. Leave some time – they’re all good stuff!)

This week marked the debut of the 32nd annual volume of the Writers of the Future anthology (Figure 3). I will not reopen the debate about L. Ron Hubbard and his non-SF works (although one might call the whole Scientology thing a fantasy); instead, I’m going to skip right over that and talk about the good that L. Ron Hubbard did for the SF/F and SF/F illustration fields near the end of his life, by starting the Writers of the Future competition.

If you’re unfamiliar with Writers of the Future, it’s an annual competition, begun somewhere around 1982, for amateur writers of SF/F, to encourage active participation in our field for those who write. There’s no fee to enter. The criteria are simple: to participate, you must “… not professionally published a novel or short novel, or more than one novelette, or more than three short stories, in any medium. Professional publication is deemed to be payment of at least six cents per word, and at least 5,000 copies, or 5,000 hits.” (Those criteria have been tightened a bit in the last thirty years to include non-print media.) Anyone, anywhere in the world, who meets the criteria above, can enter. The entries are juried by professional writers; those who become finalists are eligible to win cash prizes and be published in the annual anthology—at professional rates (some finalists are published, but don’t win prizes, just story payment). There is also an high-profile annual banquet for winners, and things like writing workshops run by top professionals (similar to Clarion). The initial judges were spearheaded by Algis Budrys, who remained involved until his death.

A few years later, the late Frank Kelly Freas performed the same service for Illustrators of the Future. At the time these contests began, there were really few ways for would-be writers and artists to break into the fields; now, literally anyone can self-publish—either on paper or digitally online—their own writing and/or graphics. However, true “professional” status is only conferred, generally speaking, by the hand of Mammon. In other words, if you aren’t getting paid, you’re still an amateur by the standards of SF/F. These contests are a terrific way to begin breaking into professional status. Many winners (both writers and illustrators) have continued their professional careers; writers who have benefited from the contest and gone on to greater things include Stephen Baxter, Karen Joy Fowler, James Alan Gardner, Nina Kiriki Hoffman, Jay Lake, Michael H. Payne, Patrick Rothfuss, Robert Reed, Dean Wesley Smith, Sean Williams, Dave Wolverton, Nancy Farmer, David Farland (editor of this year’s anthology) and David Zindell (list from Wikipedia).

The newest winners and top finalists are to be found in this book, available in paperback (Amazon, etc.) as well as e-format for the Kindle and other e-readers. Contents of Writers of the Future, Vol. 32 are:

Fiction and non-fiction

Introduction – David Farland

“Switch” – Steve Pantazis

“The God Whisperer” – Daniel J. Davis

“Stars That Make Dark Heaven Light” – Sharon Joss

“Art” (article) – L. Ron Hubbard

“When Shadows Fall” – L. Ron Hubbard

“A Revolutionary’s Guide to Practical Conjuration” – Auston Habershaw

“Twelve Minutes to Vinh Quang” – Tim Napper

“Planar Ghosts” – Krystal Claxton

“Fiction Without Paper” (article) – Orson Scott Card

“Rough Draft” – Kevin J. Anderson & Rebecca Moesta

“Between Screens” – Zach Chapman

“Unrefined” – Martin L. Shoemaker

“Half Past” – Samantha Murray

“Purposes Made for Alien Minds” – Scott R. Parkin

“Inconstant Moon” – Larry Niven

“The Illustrators of the Future” (article) – Bob Eggleton

“The Graver” – Amy M. Hughes

“Wisteria Melancholy” – Michael T. Banker

“Poseidon’s Eyes” – Kary English

“On the Direction of Art” (article) – Bob Eggleton

Illustrators are (in order of stories illustrated, same as above):

Daniel Tyka

Alex Brock

Choong Yoon

Greg Opalinski

Shuangjian Liu

Quinlan Septer

Amit Dutta

Daniel Tyka

Trevor Smith

Tung Chi Lee

Megan Kelchner

Emily Siu

Bernardo Mota

Taylor Payton

As you can see from the lists above, the book contains four articles and sixteen stories, including stories of complete fantasy, “hard” sf and everything between; each story with a full-colour illustration by one of the above artists. (Quality of the illustration is very high; I only found one or two that I felt were a bit disappointing; it appears that most, if not all, the illustration was digital, using so-called “natural” media, which can mimic the appearance of traditional media to an unbelievable degree.) In the article titled “On the Direction of Art,” Bob Eggleton, the art director for the book, explains his philosophy of how he assigned and got these illustrations for each story. Both Eggleton articles are well written and informative; I’ve long known that for the most part, where many writers would struggle to draw stick figures, artists and illustrators are usually very competent at stringing words together as well! The book also contains rules and directions for entering both contests.

Some of the more notable—better, in my opinion, although I liked all the stories—in this volume include:

“Switch,” by Steve Pantazis; it’s a police procedural novel set in the near future—in which a homicide detective, searching out the truth of a drug-related murder, learns to fight fire with fire. The illustration by Daniel Tyka’s a very good one.

“Stars That Make Dark Heaven Light,” by Sharon Joss (and its accompanying illustration by Choong Yoon) is an interesting hard SF (not technology-based, but hard SF nonetheless) about adaptation. Will we adapt humans to other planets in the future instead of terraforming?

The illustration for “When Shadows Fall,” by L. Ron Hubbard, is better than the story itself, in my opinion. Although the story (written in 1948) makes what we today would realize is an ecological point, the writing is somewhat dated. I really like the style of the illustration by Greg Opalinski, however!

“The Reactionary’s Guide to Practical Conjuration,” by Auston Habershaw, and nicely illustrated by Shuangjian Liu, is a fantasy that conjures up (sorry) a completely different world, but presents it in a way we can understand. It’s also got a little “bite” to it.

“Twelve Minutes to Vinh Quang” by Tim Napper paints a nice little picture of the future of human smuggling, refugee type, and what can happen if your only interest is mercenary. The illustration, by Quinlan Septer, is good, too.

I really like hard future technology-based space SF, like “Unrefined,” by Martin L. Shoemaker. It’s the kind of SF I grew up on, and that was promulgated by people like Larry Niven. (Speaking of which, “Inconstant Moon,” also in this volume, is probably one of many people’s all-time favourite Niven stories. If you haven’t read it, you’re in for a treat!)

And so on. I won’t mention every story and every illustration, because there are just too many of them. I liked “Poseidon’s Eyes,” by Kary English, and that’s the opposite of “Unrefined”—it’s pure fantasy, but just as well written in its own way. The thing I liked about every story in this anthology is that they—regardless of whether they’re hard SF or soft fantasy—depend on people for their impact. Every one has an identifiable protagonist who changes during the story arc; not one is left the same at the end as at the beginning, and that, for me, marks the writing as professional (not to mention setting, style, and so on.)

The articles—whether about writing (by Orson Scott Card) or writing as art (by L. Ron Hubbard) or art as illustration (by Bob Eggleton) are pithy and well done. If you’re a budding writer or artist, there’s a lot of good advice for you. I think this volume stands as a high-water mark for recent years. ISBNs are 978-1-61986-319-4 EPUB edition; 978-1-61986-320-0 Kindle edition; 978-1-61986-322-4 Trade paperback edition in case you want to order one at Amazon or your local retailer.

Capsule Review: BIG HERO 6 (2014) from Walt Disney Studios

I never got a chance to see this movie in the theatre for one reason or another; I really wanted to see the 3D version, but I finally bit the bullet the other day and watched it in 2D. It’s the animated (3D, not traditional animation) story of a robot-happy teenager in a parallel world—in a city called “San Fransokyo” (Figure 5). I’d been curious about this film, since unlike the more recent Frozen, it appears to have more or less sunk without a trace, unusual for a Disney film—especially one executive-produced by John Lassiter, who had helmed many terrific animated movies, like Toy Story, Monsters, Inc. and Finding Nemo.

Hiro Hamada is a boy genius, who graduated from high school at 13, and then spent his time playing illegal robot fighting games for large sums of money. Sort of like TV’s Robot Wars, but a heck of a lot more advanced. His older brother, Tadashi, works at a nearby university (The “San Fransokyo Institute of Technology”) in a robotics lab with co-workers “Wasabi,” “Gogo,” “Honey Lemon” and Fred, who’s just the school mascot, but who gives everyone their nicknames. Gogo has invented a bike that has magnetic wheels (no physical connection to the bicycle means a faster bike); Wasabi has invented a force field that cuts things; Honey Lemon uses chemicals to affect the physical properties of metals and other things. (Fred is… the mascot. He wants to be a fire-breathing dragon, and often runs around in a dragon costume.) The lab is run by Professor Robert Callaghan, who’s a big name in robotics. Tadashi himself has invented a “personal medical companion,” a big, soft, inflatable (huggable!) robot named Baymax.

Tadashi wants Hiro, who’s just drifting, to go to school (“Nerd school,” Hiro calls it) with him. Professor Callaghan says that if Hiro wins the robotics design competition, he gets entry to the school, so Hiro jumps at the chance, spending the next several days or weeks in his workshop in the garage at home, where he has a serious 3D printer…

…and wins the competition, with a cleverly-designed “microbot,” utilizing “magnetic bearing servo” technology, which allows more than one microbot to join up wirelessly to create larger forms. At the Student Showcase, Hiro demonstrates that his bots, controlled wirelessly by a headband neurotransmitter, can do just about anything when they link up. Not only does he win the competition (getting a letter inviting him to join the SFIT from Doctor Callahan), but he attracts the attention of billionaire Alistair Krei, who wants to buy the microbots “to help everyone.” Yeah, right. Everyone sees through that, and Hiro informs him the bots aren’t for sale. Hiro and his brother are talking outside the auditorium, when a fire breaks out inside the building. Everyone seems to have gotten out except for Professor Callaghan, so Tadashi runs back into the burning building to rescue him… just as the building explodes.

The rest of the movie, unfortunately, turns into a chase-and-fight sequence, pitting Hiro and the rest of the group (Wasabi, Honey Lemon, Gogo and Fred)—minus his brother, who died in the explosion—against a mysterious Kabuki-masked figure who seems to have stolen or duplicated Hiro’s microbot technology. I won’t reveal the ending, but I found it a bit too pat and rather disappointing.

The movie is so cleverly designed—the backgrounds, vehicles, buildings and everything else are extremely well done, ranking with (in my humble opinion) Pixar’s best work, and head and shoulders above such feeble efforts as Cars and Planes. San Fransokyo is San Francisco with a Japanese twist: for example, in Figure 5 you see San Fransokyo’s Ferry Building (at top) compared to San Francisco’s own Ferry Building (at bottom); the Japanese influence is subtle but there. Coit Tower—which was designed in our San Francisco to resemble a fire nozzle—looks like a pagoda in San Fransokyo. The characters appear well-rounded (for animation, anyway), and distinguishable from one another. Hiro even has the spiky hair (in a more realistic version) of your standard animé boy. I was very impressed with the first half or so of the movie, which runs about an hour and forty minutes. (Voice actors include James Cromwell, Damon Wayans and Maya Rudolph.) I liked the movie, but I feel it could have been so much more.

This week’s column marks almost two years of weekly effort, and I’ve been neglecting my fiction writing for that length of time. Fiction and non-fiction writing are similar, but not the same—they use slightly different muscles. So I’ve decided, with my editor’s agreement and support, to take two or three weeks off to work on my second novel, which has been languishing, waiting for my attention. Hey, if Michael Moorcock—according to the book I reviewed last week—can knock off a sword-and-sorcery book in three days, I should be able to finish a YA book in three weeks, right? Well, I have to try, anyway. I thank you all for your support over these last 100 weeks, and hope you’ll tune in to see me again when I return.

If you can, please comment on this week’s column. If you haven’t already registered—it’s free, and just takes a moment—go ahead and register so you can comment here. Or you can comment on my Facebook page, or in the several Facebook groups where I publish a link to this column. Your comments are all welcome, and please don’t feel you have to agree with me to post a comment. My opinion is, as always, my own, and doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of Amazing Stories or its owners, editors, publishers or other bloggers. See you in a couple of weeks!