Many prominent artists whose SF/F illustrative art is collected today, and who are known primarily as illustrators, spent major portions of their art careers either trying to be “fine artists” or actually succeeded in leading a “double life” as fine artists. I’m talking about artists like Richard Powers, John Schoenherr, Alex Schomburg, Stanley Meltzoff, Ron Waloltsky, Paul Lehr, John Berkey (to name only a few), artists whose names will probably be forever associated with the book and magazine covers they produced as commercial artists, who (and to varying degrees of success) also had the ambition and desire to create gallery art, and be recognized as “fine artists.” And isn’t it “ironic,” notes a collector of the work of Richard Powers, when recommending this topic for my post, “that the works these artists valued the most (their fine art) were typically not collected or valued nearly as much by collectors (of illustration)?

To be clear, I am not talking about commissioned but unpublished work produced by SF/F illustrators, or “portfolio pieces” that commercial artists create in order to show what they can do, in order to get jobs. I’m not talking about “stock” paintings, produced in advance of any particular assignment, in hopes of (or with the goal of) it being used (as Powers did). Or artwork created to fill holes in a planned publication, such as an artbook or set of collectible cards (as Berkey did). Nor works created for private commissions.

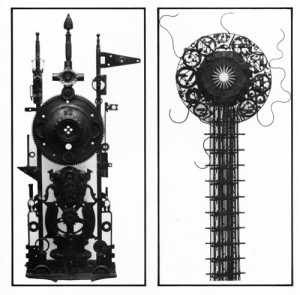

No: I am talking about art produced by illustrators that would not, could not, be mistaken for their illustrative work, such as Paul Lehr’s sculptures in wood, stone, and welded metal, or Alex Schomburg’s “Autumn”

Works like “Autumn” looked nothing at all like the cover art Schomburg produced for early pulps, beginning 1925, nor did they resemble in any way his comic art for Marvel in the 1940s, or even the science fiction magazines he illustrated in the 1950s and onward. . . . works for which Schomburg became justifiably famous.

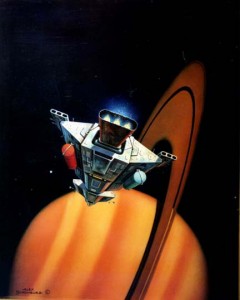

“Saturn,” for example, was a painting that, even undated, and with commercial use unknown, was so colorfully representative of the artist’s work that it was featured in CHROMA: the Art of Alex Schomburg, 1986. (p. 83), chosen by Vincent DiFate to illustrate Schomburg’s biographical entry in Infinite Worlds 1997 (p. 270), and later saw reproduction in the special article on Schomburg published in Illustration Magazine issue #13 (2006). So I had no trouble selling it for my asking price, $3000, in 2006. The same could not be said for “Autumn.” Although nicely done, and also featured in Chroma, this was seen as just a pretty landscape, dating from the time he moved West, to Spokane, WA and started producing personal fine art pieces in oils (and winning prizes for them). As such, it not only was atypical of the work he was known for, but was not highly valued as “fine art” either…as I soon learned. As a result, this painting sold for 50% less than “Saturn” . . . but found a good home thanks to Susan Schomburg, gallery owner in California and the artist’s granddaughter, who was delighted to buy this “fine art” work because of its “deep sentimental value to our family” (correspondence, 2006). The family preserves the legacy of Schomburg’s work in this way, and through exhibit, but doesn’t sell it; a factor which undoubtedly contributes to the lack of a market for his fine art.

Why some artists, historically (and ongoing) are unsatisfied by careers devoted to producing art for commercial use, while others have been perfectly happy in their roles as “hired wrists” for the whole of their working lives, could fill a book, let alone a blog. The reasons are as diverse as the artists themselves. Suffice it to say, however, that regardless of their rationales, artists I’ve known who were driven to enter the highly competitive, weird world of “fine art,” also tended to think much more highly of themselves as artists for having gallery shows, and gaining gallery representation, although such efforts (and success in those arenas) might not be made known to (or be hidden from) collectors of their illustrative works.

John Berkey, best known for his space and science-fiction themed works, was a difficult “sell” when it came to his personal works, of which he was very proud.

They weren’t terribly expensive, given their quality; but no one wanted his posed studio nudes, his rock “still lifes” or his more surreal figurative works, like “The Swing.”

The fact that he may have shown, or even sold a few landscape paintings of midwestern farmhouses at some gallery somewhere were of little interest and no concern to his collectors of SF illustration. They didn’t want them.

You might suppose that Richard Powers’ “fine art”, because it differed so little in style from his published illustrations, would have enjoyed the same success and reputation in both illustrative and fine art collecting markets. But that didn’t happen. While early in his career his work was shown in the Whitney, and the Rehn Gallery in Manhattan represented him for more than two decades, the fact remains that what the “SF world” viewed as incredibly innovative and different and “influential” the fine art world, it turned out, did not.

As a result, there is no discernable market for his Monhegan Island seascapes, his portraits of Picasso, and his experimental concoctions with 3D elements. Indeed, SF collectors will pay a third to as much as 10 times less for his unpublished abstract works (as by Gorman Powers, or Powers) as for his better known book illustrations (as by Powers laz/org). Even when they look almost identical in style and execution.

Despite their high quality, and positive reception in galleries in Europe (where he showed his fine art for years) the clearly experimental surreal abstract style was just too strange and off-putting for SF fans without a literary association to help them appreciate it. :-)As you may have noticed, to make my argument I have relied on artists who are “no longer with us”. There are good reasons for that. Perhaps the most important of them has to do with the collector’s comment above (which I agreed with), relating to the market value of these artists’ fine art today. A secondary market has been established for these artists’ illustrative works, and it is against these sales, most practically at public auction, that it is possible to make comparisons between what buyers have judged to be “desirable” and “less desirable” works. In other words, “the jury is in” for these artists’ “fine art” as well as atypical, unpublished, personal works, but for obvious reasons, the “fine art” efforts of those contemporary (i.e., living) artists’ who have attempted to follow the same path, either straddling both fine art and illustration, or switching fields entirely to become gallery artists, cannot yet be judged. These artists are still producing work, there is little to no secondary market existing for many of them, and, in some cases, the prices paid in the primary market for their gallery “fine art” has greatly superseded anything ever realized for their illustration art, once they left the commercial field: Some examples include Michael Whelan, Morgan Weistling, Gary Ruddell, Jim Warren. But how will they be remembered? As illustrators who spent part of their career in fine art (like Powers), or as “fine artists” who spent part of their career as illustrators (like Warhol)?

My series of “where are they today” postings, in fact will feature some contemporary artists who have dropped from (or not stayed in) view as “illustrators” specifically because they expanded their horizons or shifted to other art markets and industries, including “fine art.” This has brought mixed results: in some cases this has affected the value of their illustrative works in a negative way, while in other cases the effect on the prices of published work has been positive. The situation is fluid, and difficult to generalize about, because the field has grown to the point where the distinctions between what would be described as illustrative works (on the basis of style and execution and subject matter) and “fine art” (on the basis of style, execution and subject matter) are blurring. There are several reasons for this – among them the tastes and differing expectations of New collectors who are entering the field. For one thing, and unlike previous generations of collectors of SF/F art, most would not describe themselves as collectors of illustrative art. Because they don’t care (as much as I did) whether it was used, for a game or a book or calendar, or not.

I’ll be returning to, and expanding on, this thought in future posts. Just like artists still straddle the “fine art”/illustration fence, collectors are also having to adapt to new collecting times . . . because one of the main characteristics of this kind of art is no longer operable: that its raison d’etre was as a marketing tool.

Really enjoyed this and look forward to future “where are they now” ARTicles.