Today we begin a new bi-weekly feature that introduces the art and history of the members of the International Association of Astronomical Artists (IAAA), a group of artists who have as their collective forte the illustration and presentation of scientifically accurate depictions of space, the planets and the hardware that we will use to get there.

The organization founded in 1982 at an artists workshop hosted by the Planetary Society; following several additional annual workshops, the organization was formalized in 1986 and has been growing in membership, scope and impact ever since. Workshops at exotic locations that serve as analogues for distant planetary realms are regularly held and a traveling exhibit is constantly on the move.

While ‘space art’ is often confused with science fiction and fantasy art (indeed many of the IAAA members work in more than one field and will be familiar to many genre fans via the enormous number of illustrations they’ve produced that grace the covers of books, magazines and websites; and it is not unusual at all for an illustration to do double duty – witness many of the covers for magazines such as Analog and the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction over the years), the organization fairly and firmly points out the difference:

The IAAA was founded in 1982 by a small group of artists who journeyed through the fascinating but seldom trod territory where science and art overlap.

From these pioneering astronomical artists (unlike their colleagues in science fiction and fantasy, with whom they are sometimes confused by the uninitiated), a firm foundation of knowledge and research is the basis for each painting. Striving to accurately depict scenes which are at present beyond the range of human eyes, they communicate a binding dream of adventure and exploration as they focus on the final frontier—space. – IAAA.org/manifesto.html

The IAAA is firmly grounded in a long-standing tradition of explorer-artists:

In the 1800s, artists accompanied explorers into the frontiers of the Americas and sent back colorful images of the new lands. Paintings from Thomas Moran and Albert Bierstadt spurred further exploration of the West, and helped to preserve Yellowstone, Yosemite, and other areas as national parks. In 1872, Frederick Church, the highest paid painter of his day, financed his own expeditions to paint polar aurorae, icebergs in the Arctic Sea, and volcanoes in South America. But soon, the Earth’s frontierlands disappeared and the link between art and exploration broke down.

Today, we receive images from a new frontier that is rapidly expanding, planet to planet, into space. A new link is being forged by a new generation of exploration artists—Space Artists. Armed with science, creativity and imagination, they construct realistic images of visions throughout the Universe, from our Earth to the Stars. Not only realist; surrealist and impressionist styles are equally valuable in this adventurous and innovative field.

Space art serves the most basic function of fine art, that of inspiration. It directs our focus toward the space frontier, where human destiny inevitably lies. We are in the midst of a human adventure that will be remembered when the international squabbles of our century are long forgotten. We are stepping off ancestral earth and learning what wonders and resources are scattered throughout the starlit blackness of space. It is an adventure for artists, scientists and all mankind.

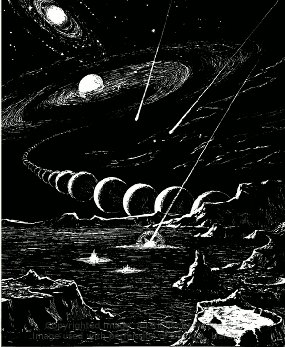

Many of us are more than passingly familiar with the work of Chesley Bonestell (a recipient of the IAAA’s Lucien Rudaux Memorial Award and Hall of Fame inductee); indeed, his illustrations in books such as The Conquest of Space and The Exploration of Mars (written by Willy Ley and Willy Ley & Werner von Braun respectively ) fueled my imagination at an early age and occupied equal time with the SF novels of Heinlein, Le Guin, Bradley and Chandler that I was just beginning to become familiar with. An experience that will be familiar to many fans of the genre.

Many of us are more than passingly familiar with the work of Chesley Bonestell (a recipient of the IAAA’s Lucien Rudaux Memorial Award and Hall of Fame inductee); indeed, his illustrations in books such as The Conquest of Space and The Exploration of Mars (written by Willy Ley and Willy Ley & Werner von Braun respectively ) fueled my imagination at an early age and occupied equal time with the SF novels of Heinlein, Le Guin, Bradley and Chandler that I was just beginning to become familiar with. An experience that will be familiar to many fans of the genre.

Two other artists less familiar to US audiences than Bonestell also helped to establish the field of scientifically accurate astronomical art with pioneering work in the illustration of worlds beyond our own: Lucien Rudaux (1874-1947) and Ludek Pesek (1919 – present). All three are profiled in this excellent article by Ron Miller, himself a member of the IAAA. Both gentlemen are also recipients of the Lucien Rudaux Memorial Award and inductees into the organization’s Hall of Fame.

It is often said that human beings are visually-oriented creatures. The time-worn expression “a picture is worth a thousand words” is more than testament to that conceit. The value of envisioning technically accurate locales, craft and environments has long been understood by those working towards the planets and the stars; Bonestell’s illustrations in the 50s are credited with generating popular support for the US’s flagging space program. Today, many of the members of the IAAA work with observatories, national and private space programs (Robert McCall, Hall of Fame inductee and illustrator of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey promotional art was commissioned to prepare space art murals for NASA and the National Air and Space Museum, works that are viewed by millions annually) and aerospace companies to turn imagination into reality.

If we can see it, we can believe it. If we believe in it, we can turn it into reality.

~~~

David A. Hardy is a past (and first European) President of the IAAA. The following retrospective of his artwork originally appeared in the August 2012 ‘re-launch, pre-launch’ issue of Amazing Stories and has been slightly updated with new illustrations provided by David. In the weeks to follow, Amazing Stories will feature the artwork of many other members of the IAAA.

Retrospective: David A. Hardy

The King of Space Art

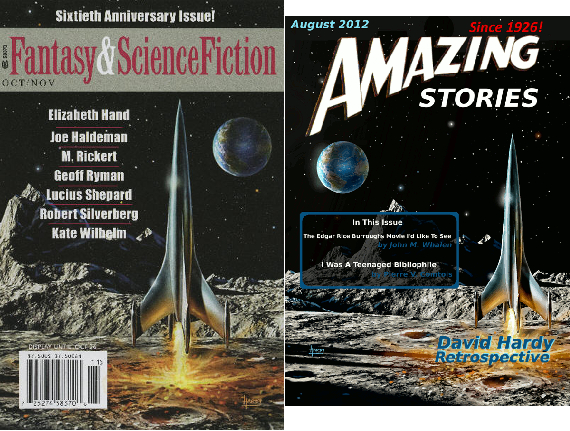

The cover illustration of the August 2012 issue of Amazing Stories may look familiar to many because it is because it is a slight re-working of a cover that David A. Hardy – the subject of this present art retrospective – prepared for the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, the 60th anniversary issue of that iconic magazine to be exact (Oct/Nov 2009).

- F&SF 60th Anniversary Issue & Amazing Stories, August 2012 Issue (Note the slight alterations between the images)

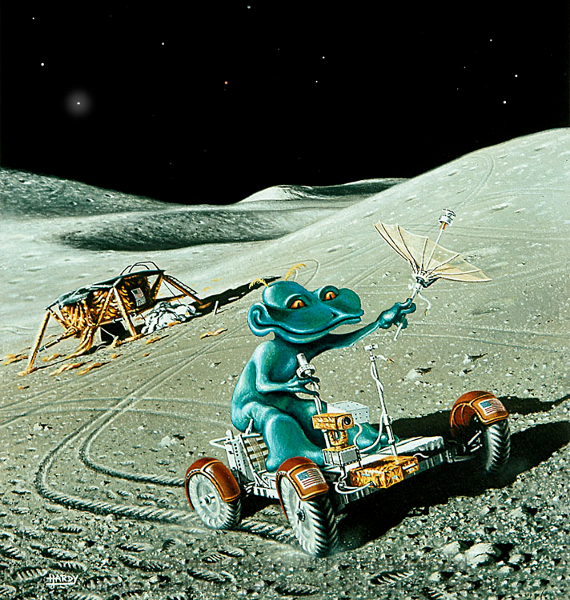

Mr. Hardy’s artwork gracing the cover of F&SF’s 60th birthday is unsurprising considering the large body of his work that had already appeared there. Anyone familiar with that magazine will be familiar with Hardy whether they know it or not, including his whimsical space alien Bhen.

Bhen was co-designed with cartoonist friend Anthony Naylor and was first featured on the cover of F&SF in 1975. He was frequently seen putting NASA hardware to unorthodox uses on nearly a dozen covers between 1975 and 1994.

But let us back up for a moment to earlier days, days filled with dreams of space and promise.

Towards the end of WWII an architectural illustrator and matte painter named Chesley Bonestell had begun selling his illustrations of space to a number of popular magazines such as Life and Coronet. Bonestell’s work was so scientifically accurate and offered readers visions of worlds they were just becoming familiar with that were so breathtakingly inspiring, that he eventually began working with real rocket scientists such as Willy Ley and Werner von Braun, illustrating their projects, plans and ships, making them real for a public that was just beginning to think of space as a place they could go.

In 1949, Ley and Bonestell published The Conquest of Space (a book that should be familiar to any baby-boomer). Bonestell’s illustrations were so realistic and convincing, Ley’s presentation so straight-forward and seemingly pedestrian that it helped to launch the popularization of space exploration. (With many of us wondering why we couldn’t leave tomorrow!)

The timing couldn’t have been more perfect for an English lad named David A. Hardy, who was at that “golden age of science fiction” – or just about ten, or eleven, or twelve. That age when we are still able to accept that there is wonder in the world and old enough to be able to appreciate it.

David was inspired by Bonestell’s work and would begin illustrating shortly after being exposed to it. In 1954, he landed his first book, illustrating Suns, Myths & Men by the english astronomer Sir Patrick Moore. He was 18 at the time, beginning a long and successful career that continues to this day. It was a relationship that would continue to endure to this day; David still appears on Sir Patrick Moore’s BBC television show The Sky At Night.

David strives for astronomical accuracy in his work, consulting all of the latest reports and findings and working them into his illustrations. In 1952, when David was 16, there were no rocketships, no space probes, no space telescopes. What little was known about the Moon and other planets was restricted to ground-based astronomy. Nevertheless, David turned out this illustration of a Moon landing for a proposed British Interplanetary Society project:

The lander is stunningly LEM-like for its time; it would be nearly another 6 years before Sputnick would beep around the world, 17 before Apollo 11. This is also David’s first published work, appearing in a local newspaper along with the title “David Has Some High Ideas.”

Another image following the same theme, this time a bit earlier in the mission: The Lunar surface detail is incredible and could almost be a photograph of a low-powered telescope image!

David’s work on Suns, Myths & Men provided him with stellar (pun intended) credentials: (the late) Sir Patrick Moore was and remains the UK’s most prominent space popularizer. David would go on to work on several other titles with him over the years, including Challenge of the Stars (1972); New Challenge of the Stars (1978); and Futures: 50 Years in Space (2004; nominated for a Hugo and awarded the Sir Arthur Clarke Award in 2005). ‘Futures’ would be followed two years later by a paperback edition 50 Years in Space, (2006), and Mars The Red World, helping to establish him as a go-to artist for scientifically accurate depictions of space.

David’s work on Suns, Myths & Men provided him with stellar (pun intended) credentials: (the late) Sir Patrick Moore was and remains the UK’s most prominent space popularizer. David would go on to work on several other titles with him over the years, including Challenge of the Stars (1972); New Challenge of the Stars (1978); and Futures: 50 Years in Space (2004; nominated for a Hugo and awarded the Sir Arthur Clarke Award in 2005). ‘Futures’ would be followed two years later by a paperback edition 50 Years in Space, (2006), and Mars The Red World, helping to establish him as a go-to artist for scientifically accurate depictions of space.

Illustrating space is not without other-worldly rewards either: In 2003, the asteroid 1998 SB32 was officially renamed for the artist – asteroid Davidhardy.

During the years intervening between his start in 1954 and today’s illustration appearing here in Amazing Stories, David has traveled around the globe numerous times. (indulging his passion for volcanoes among other things); his work was favored by Amazing Stories alumni including Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke (he just missed out on an opportunity to illustrate the Clarke/Kubrick collaboration 2001: A Space Odyssey, a tale featured in his book Hardyware!) and Carl Sagan among others. He is also currently a VP of the Association of Science Fiction and Fantasy Artists and has been nominated for their Chesley Award numerous times; has received the Best Cover Art Reader’s Award from Analog magazine, been nominated for the Best Artist Hugo Award, and has received both the Sir Arthur C. Clarke award for Best Written Presentation and the Best European SF Artist award.

David A. Hardy is, in fact, the King of Space Art, having been at it longer than any other artist currently practicing in the field, and it is easy to see why.

I think it important to express how critical the artist is to both the scientific exploration of space as well as to science fiction. Human beings, it is said, are visually oriented creatures. We can’t really gain a true understanding of something until we’ve seen it with our own eyes – which presents problems for trying to understand things we can’t see or that don’t yet exist. This is where artists like Hardy enter the picture.

No one knew what the Moon really looked like down on the surface until artists like David began illustrating it for us, and then we all wanted to go. And of course most of science fiction is concerned with things that are not yet of this world; authors can be extremely effective in conveying images, but as they say a picture is worth a thousand words.

David is keen to express the difference between the two disciplines, as he did during this interview with UniverseToday earlier this year:

I do feel that it’s quite important for people to understand the difference between astronomical or space art, and SF (‘sci-fi’) or fantasy art. The latter can use a lot more imagination, but often contains very little science — and often gets it quite wrong. I also produce a lot of SF work, which can be seen on my site, and have done around 70 covers for ‘The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction’ since 1971, and many for ‘Analog’. I’m Vice President of the Association of Science Fiction & Fantasy Artists (ASFA; www.asfa-art.org ) too. But I always make sure that my science is right! I would also like to see space art more widely accepted in art galleries, and in the Art world in general; we do tend to feel marginalised.

Examples of the attention to detail – and his ability to imagine the non-existent – are amply illustrated here.

After serving in the RAF (during which time he continued to illustrate), David did a stint as a commercial artist for Cadbury, the candy company and then struck out on his own in 1965.

Since that time David has provided illustrations for televisions shows – including Blakes 7

A UK based show. David was asked to illustrate the planets that would appear in the background and through ship portals during the show’s second season.

He has also been asked to illustrate some of science fiction’s most iconic images, including Dr. Who and the Daleks.

This image showing Westminster and the invaders was created for Dr Who: The Dalek Invasion of Earth by Terrance Dicks. Why the Daleks choose to invade at 3 is something you’ll have to ask David.

David is capable of humor as well, as illustrated by this faux SF magazine:

that graced the cover of a CD from the British National Space Center. (The ‘spoof’ was that while it looked like a pulp magazine, the content was all serious science).

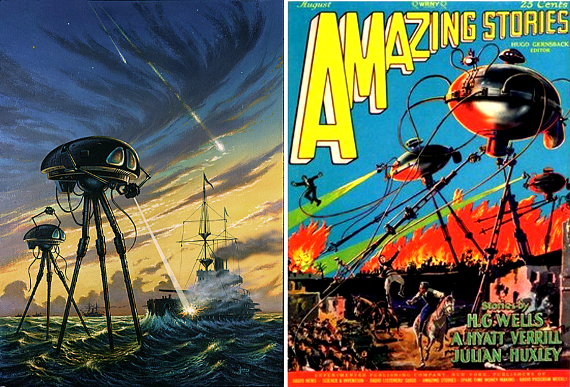

David’s work has also been admired (and purchased) by members of the rock community, including The Rolling Stones and Queen. He was originally asked to illustrate Jeff Wayne’s musical version of the Well’s story and produced what has become one of his most recognizable pieces – Martian Tripods attacking the HMS Thunderchild. (In the novel, the ship sacrificed itself while successfully protecting civilians who were escaping London.)

I have to admit that this is certainly one of my personal favorites. Until the advent of this picture, I considered Frank R. Paul’s illustration of a similar scene on the cover of Amazing Stories to be the best I’d seen for Wells’ novel. Now I just put them side-by-side and don’t bother trying to pick one over the other:

Paul’s illustration is frenetic, over the top and mechanical. Hardy’s (benefiting from several decades of intervening knowledge) shows us a smoother blending of the real and the fantastic, as do these other pieces:

Lift Off, a frequently reproduced illustration, is the perfect evocation of science fiction’s sensawunda: where is this? what was the ship doing there? why is it leaving now? where is it going? We’ll never know the answers, but that’s at least half the fun.

The following mission has not happened yet, but this illustration – Comet Probe – occupies the middle ground in David’s work, straddling the divide between fantasy and reality.

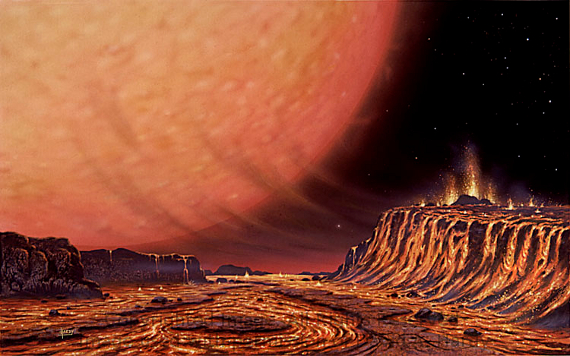

Several years ago it was discovered that Io (one of Jupiter’s Galilean satellites) was an active planet; several planetary probes caught “ice geysers” in profile against the planet’s rim. We learned that such things happened for real, but it took David Hardy to give us a much better idea of what it would look like from ground zero:

It also takes an artist to show us what the future holds for our solar system –

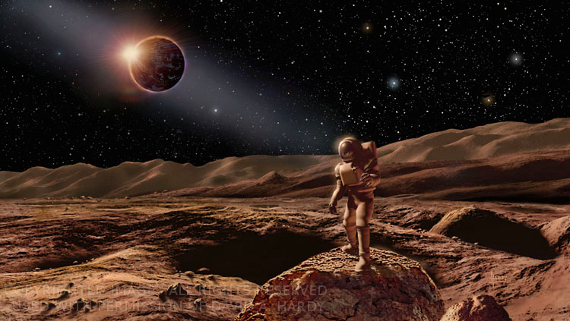

and to give us some idea of where we may go someday:

Back down to Earth. David has a way of creating imagery of things and places we could actually see with our own eyes, but presents them from a perspective – a time and a place – that few of us would think to employ:

And he also creates evocative images of things we all ought to be able to see with our own eyes:

All of the illustrations here were generously provided by David for this article; he even touched up the graphic that heads up the excerpt to his story Aurora that appears elsewhere in this issue.

David A. Hardy has recently revamped his website and offers prints of nearly all of his works (for extremely reasonable and affordable prices). That site can be seen here – AstroArt.

There are also several interviews and gallery displays of Mr. Hardy’s work on the web, including:

a biography on SS3F

a 2004 interview on UniverseToday

a more recent interview and gallery on the same site

a gallery at Outer Space Art Gallery

and a small gallery and prints on Nova Space Art

I hope you all enjoyed this trip through David’s work and choose to pay him a visit on his website.

2 Comments