OBIR: Occasional Biased and Ignorant Reviews reflecting this reader’s opinion.

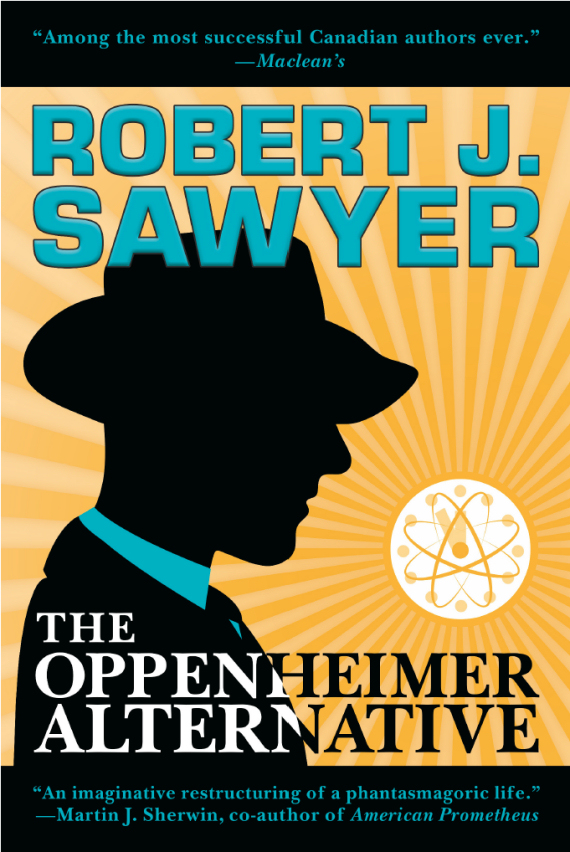

THE OPPENHEIMER ALTERNATIVE – by Robert J. Sawyer

Publishers: Red Deer Press, Canada, & SFWRITER.COM Inc., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada, 2020.

Editor: Adrienne Kerr

Cover Art: BiblioFic Designs

Premise:

A group of physicists have to develop an atomic bomb to ensure the Allies win World War II. That much is history. It’s what they have to develop next in order to save the world from a previously unknown threat which provides the alternative history aspect of this novel.

Review:

This book has already been reviewed for Amazing Stories by my friend and fellow columnist Steve Fahnestalk. He did a masterful job discussing the intricacies of the plot, the historical background, and the original, creative elements Sawyer added to turn remarkable history into remarkable fiction.

So, what’s left to comment on? My personal fascination with some of the real life characters, which is what drove my eagerness to read this novel. In particular I wanted to experience Sawyer’s take on, not so much J. Robert Oppenheimer himself, as General Leslie R. Groves, Edward Teller, and Wernher von Braun. The latter three I’ve always viewed as the most eccentric characters involved in the Manhattan project and its consequences in the immediate postwar period. Several movies and a number of books left me with the following impressions:

General Leslie R. Groves – Gung-ho, stiff-necked, inflexible, authoritarian, and ruthless.

Wernher von Braun – Brilliant, charismatic, charming, calculating, ambitious, and ruthless.

Edward Teller – Brilliant, devious, cynical, self-centred, near-psychopathic, and ruthless.

Robert Oppenheimer – Brilliant, quiet, easy-going, decent, dedicated, and mindful of others.

Knowing Sawyer’s penchant for in-depth research, speculative extrapolation, and empathetic characterization, I couldn’t wait to read his views on these and all the other peculiar characters involved. Figured I was in for a treat. I wasn’t wrong.

However, I noticed a couple of reviews online that reached a negative conclusion. One complained the Dramatis Personae at the beginning listed 63 characters. Way too many! according to the reviewer, who seemed to be implying this was, as a result, a flawed, rather bizarre science fiction novel. Another complained there wasn’t enough science, that it was impossible to follow the development of the Manhattan project because characterization ruled the text, not the essential scientific conundrums. Seemed to be saying the book wasn’t about the Manhattan project, but rather about the people in it, as if this were a bad thing. Said reviewer threw away the book after reading just two or three chapters. Both these individuals not critics as such but “ordinary” readers. One could argue that this does not bode well for the popularity of the book, except that the vast majority of reviews I came across enthusiastically praised it. So, what’s up with these two guys? Why did they find the book disappointing?

I think I know. When I first began extensive reading of science fiction a lot of golden oldies were being reprinted in paperback for the first time. The complete series of series by Edgar Rice Burroughs, for example. A lot of splendid novels from the fifties were still in print. Yes, there were characters, but concept was King, nifty ideas that stirred my sense of wonder. A good many characters were just add-ons to flesh out the plot, to give the concept some context, something to hang on to. I could care less about their personal problems; I was only interested in the problems arising from their attempts to grasp the concept they were facing.

Then along came the New Wave. Suddenly people were inserted into the stories, people with individual problems, people afflicted with anxiety and self-induced personal pressures, people flooded with angst, a bunch of mundanes struggling to cope with many of life’s problems involving human interaction that I was already familiar with. People with sex lives, for Ghu’s sake! As an immature young adult (today I’m a full-grown immature senior) I fled the science fiction scene; I abandoned reading science fiction. It was no longer what I craved, no longer the eye-opening nifty exploration I had become addicted to. Instead, it was all about people, the greatest mystery of all, a conundrum I had enough difficulty dealing with in real life. The dread spectre of sophisticated characterization had reared its myriad Hydra heads.

I got over it. I avoided reading science fiction for seven years or so. Then, having grown up a little bit, began reading the genre again. Still lots of mindboggling core concepts presented, but now wrapped in layers of subtly and sophistication hitherto unknown to my ability to grasp human nature. Many a new SF novel much more like classic, literary novels. This is actually a good thing. Makes for meatier, more satisfying reads, providing originality and innovative thinking are present in abundance.

Here Philip K. Dick helps me out. Recently Mike Glyer, a legendary fannish personality, posted a clip on his news website File 770 showing a portion of an interview of Philip K. Dick at a convention in France in 1977. Bear in mind Dick was notorious for talking “at” people rather than “with” people, a man of many monologues. He was also notorious for tailoring his “lectures” to the audience; in this case sucking up to the French. Nevertheless, he had many interesting comments to make contrasting French readers with American readers.

First, that Science Fiction was considered “kiddie” stuff in America and that publisher’s policies were dictated by the need to sell to libraries, taking into account that librarians were adamantly opposed to sex and violence in children’s books, such that that publishable SF was possible only if the writers practiced a limiting, self-censorship. Second, America was profoundly anti-intellectual, always had been, and always would be. Third, science fiction was trash as far as academics were concerned, something no serious critic had any business reading. Consequently very few people read science fiction, and those that did were not up to appreciating his writing. I’m paraphrasing like crazy but I think you get the gist. Namely, that the French, in contrast to Americans, were profoundly adult, sophisticated, and intelligent, and they alone were capable of understanding and appreciating he and his works. Really? The nation that gave the Legion of Honour medal to actor Jerry Lewis? Still, he’s not all that wrong. Science Fiction was stuck in its own ghetto in North America till very recently and is not entirely free even yet.

But the most stunning revelation from Dick was that he had not read much science fiction and did not consider science fiction literature the basis of his science fiction. He went so far as to condemn the contemporary American SF readers for reading “only” science fiction and knowing nothing about literature as such. He claimed that his writings were inspired by 19th century French social realism, writers like Balzac and Zola, and by 19th century Russian writers who wrote in imitation of the French, Russians like Turgenev. He saw himself as combining the French Naturalist movement with the penetrating, comedic cynicism of Kafka. Well, dang. I don’t know if he was telling the truth, but it certainly makes sense, considering the nature of most of his novels. He seemed to be saying he had grown out of the pulp fiction ghetto into something only the French could truly appreciate. Certainly, his interview was a masterful sucking up to the French; no doubt it made French intellectuals tingle all over.

If I remember correctly, I believe one of the points he made was that a multiplicity of characters was something American readers couldn’t handle (in 1977). Or now, judging by the person who rejected the 63 characters listed in the Dramatis Personae for Sawyer’s book. It didn’t bother me. I just skipped through the list, looking for names already familiar to me, using them to orient myself to a general sense of what the novel was likely to be about.

If anything, Sawyer set out to write a novel designed for people like me. The scientific explanation is kept to a minimum, just enough to allow the reader to grasp what the characters are arguing about, and to follow along as the character’s understanding of the science evolves over time. Anything more would have made my eyes glaze over. The essential conundrums are laid out, the subsequent attempts to grasp the implications and resulting conclusions and solutions clearly explained. Perfect.

I do not for a moment believe the science background is what drew Sawyer to write this novel. It’s the characters. The utterly fascinating, fantastic personalities of the real people behind the creation of nuclear weapons. How could any writer worth his salt resist defining these prima donnas for what they were and would likely have become had certain scientific problems showed up to threaten all of mankind beyond the mere threat of nuclear war? An opportunity to define not only a bunch of wacky weirdos but an entire era of off-the-cuff madness whose ramifications are with us still. I suspect Sawyer sank his teeth into the task of writing this novel with all the glee and focus of an apex predator ravaging a herd of herbivores. A writer couldn’t ask for a better meal of eccentric prima donnas to work with. A delightful challenge. I’d even go so far as to assume Sawyer enjoyed researching and writing this novel more than any of his previous novels. It must have been great fun.

Thing is, one of the things Sawyer is noted for is his social realism, in that his novels often take place more or less in contemporary times, usually with Canada as a setting, with characters generally occupying normal, or at least, real occupations. Their problems tend to be grounded in typical human preoccupations. Always, of course, until an extraordinarily unusual problem becomes their main preoccupation, but all the same it can be said his novels are about real people dealing realistically with whatever “impossible premise” is behind the plot of the novel. In that sense, whether consciously or not, his novels are written “as if” they follow the French literary tradition of social realism or naturalism. In short, his novels exhibit the kind of complex and subtle sophistication Philip K. Dick was talking about as the ideal method of writing science fiction. Academics don’t seemed to have twigged to this. It’s why Sawyer doesn’t bother much with writing to please the academics (or such is my impression) as he has a more important readership in mind, namely the people who like the stuff.

For one thing, unlike me, Sawyer doesn’t pontificate. His writing style and technique is deceptively clear and precise and very easy to read. He doesn’t let anything disrupt the flow. Once he’s got you hooked, every book, and especially this one, is a real page turner. Only later, upon reflection, does the complexity and subtlety of what he’s writing sink in. His teeth rip into your subconscious, then take their time to penetrate upward into your conscious awareness (to carry my stupid carnivore analogy further).

Having so many characters is no problem whatsoever for an author as skilled and experienced as Sawyer. He makes sure the focus is on the relationship, one might say the competition of one-upmanship, between the relatively few main characters present throughout the novel. All the other characters serve their historical and fictional purpose without distracting or confusing the reader because the context of their behaviour and action is made crystal clear. Context is everything. Context is the matrix on which characters are exhibited, and Sawyer is a master at this. I had zero problem keeping track. No mean feat, considering how easily I can be confused. (Just ask my former employers.)

The Manhattan project, and typical academic think-tank institutes, can be described in terms of buildings and other infrastructure, and scientific problems in excessive detail as a type of puzzle, but Sawyer uses these elements as mere context, a form of background setting, with his focus on the human problem of the main character’s personal lives, the masks they present to others, the illusions and delusions they offer themselves, and above all, their obsession with doing the right thing, or more accurately, with proving themselves right and everybody else wrong. This is what makes The Oppenheimer Alternative an exciting read.

The beauty of this approach is that it brings the process of creating and running the Manhattan project truly to life and makes it meaningful to the reader. It wasn’t just a ‘thing,” a sweltering hot mess of Quonset huts and shacks atop a desert mesa, but a kind of hive mind devoted to a collective purpose yet riven by clashes between prima donnas invincible in both their god-like arrogance and deep-seated insecurities. Brilliant people so obsessed with their purpose and themselves as to avoid thinking about larger issues like family and civilization. And when they did attempt to “solve” the larger issues with the same analytical talents they applied to the job at hand they almost always buggered things up. Being a Brainiac by no means a solution to life’s problems it seems. A hindrance, in fact. Revelations to this effect through Sawyer’s interpretation of the characters render the Manhattan project thoroughly relatable and understandable. It’s all about people, after all. Sawyer makes this very clear. Now I “get it.” Now the whole phenomenon makes sense to me.

Of course, to understand the Manhattan Project and the subsequent McCarthy-era witch hunt the reader also needs to understand the mentality of the time, not just that of the individuals involved but of society as a whole. Here the depth of Sawyer’s research shows, but not through info dumps. Instead Sawyer presents the ongoing problem of coping with changing circumstances by delving into the character’s minds and their thoughts. This gives the reader a real sense of fly-on-the-wall status keeping pace with the characters’ desperate struggles to comprehend what is happening to them. Greatly aids the sense of drama.

Ah yes, the characters. Specifically the main characters. Did reading The Oppenheimer Alternative give me any fresh insights? Alter my previous opinion of each?

General Leslie R. Groves: I had previously thought of him as a sort of buffoon, a walking cartoon of a man, a living cliché of a no-nonsense military thinker incapable of treating people as people. Darned if he doesn’t come across in this book as someone nearly likeable. He’s portrayed as an admirably clear-thinking administrator with his eye on the essentials and rather impatient with artsy-fartsy airy-fairy eggheads whose interest in atomic weapons is solving an elegant problem rather than developing a war-winning weapon. Groves comes across as an intelligent herder of cats, one open to suggestions as how best to accomplish this. No kneejerk fanatic, he is even willing to protect the scientists from those who would kneecap them for petty political purposes, if only because he recognises how truly valuable they are. I am forced to conclude he was probably the right man for the job.

Wernher von Braun: Plays a relatively minor role, though a significant one. Sawyer mentions his charismatic influence with the public but concentrates on his brutalist relations with those who stand in his way. Wernher is quick to dismiss anyone who doesn’t serve his purpose. I think Sawyer is implying von Braun was never a committed Nazi ideologue as such, but was so callously calculating and opportunistic his S.S. uniform suited him very well as an expression of his personality. He knew about the criminal treatment of slave labourers at the Dora facility where V2s were manufactured and literally didn’t give a damn. Not then and not ever. In fact, I’m certain he would have tolerated the same level of cruelty if that’s what America had to do in order to build the Saturn Five rocket launch vehicles he and his team designed. I think Sawyer caught the inherent coldness of his nature very well. I remember thinking Werhner von Braun was a terrific guy when I saw him on the original Disney space series. Less so when I grew up and learned more about him. On reading this book I’m now convinced he was essentially an absolute bastard. I understand the US government’s personal file on him is still classified. Probably for reasons beyond what is currently public knowledge. Not a nice guy at all.

Edward Teller: He has been subject to more criticism from liberal circles than von Braun. The latter restricted his postwar public enthusiasm to rockets and space travel. Teller was the father of the H-Bomb, and enthusiastically so. As Sawyer makes it abundantly clear, he firmly believed it should be used on the Soviet Union, and the sooner the better. Still, there were occasions when he had doubts about his stance. Sawyer manages to make him, if not a character readers can sympathise with, a character readers can understand. He had personal reasons for being so virulently anti-communist. He could, on occasion, with family and the very few individuals he trusted, be decent and pleasant, but generally tended to relate to others according to his principles. Trouble is, and this was his major character flaw, he bore grudges to the grave. Any perceived slights he took as justification for life-long contempt and hostility toward the people who had offended him. A hard man to get along with. Sawyer hints even Teller found it near impossible to get along with Teller. This makes Teller even more fascinating to me.

J. Robert Oppenheimer: Sawyer has wrought the most radical transformation of all, in that I now understand Oppenheimer to have been extraordinarily complex. Turns out he was a lot like me. Not as egotistical as that sounds. He seems to have drifted through life with a passive personality, going with the flow, occasionally rousing himself to the task of taking on responsibility for himself and making decisions, albeit ones that usually turn out to be mistakes that cause no end of complications and trouble. He tended to take refuge in an “objective” cynicism that rendered him immune to actual involvement with the problems at hand. I’m a bit like that. I like to keep problems at arms length.

Where Oppenheimer and I differ is his near magical ability to tolerate the foolishness of others, to let them vent past each other and calm down to the point of working together. Groves instinctively recognized Oppenheimer was perfect for the role of assistant cat herder. Consequently, more often than not, they suited each other’s purpose very well.

Of course, the most obvious difference between Oppenheimer and myself is that he was a genius and I’m not, to put it moderately. Yet, the way he’s portrayed in this novel, he seems to have had a habit of overthinking everything and indulging in naive wishful thinking, only to be brought up short by brutal realty now and again. I can empathize with that. Occasionally, when he thought it was necessary, he was hard-headed and manipulative but seldom with any degree of success. I, too, normally avoid confrontation. Thus, I find it easy to identify with him.

Of the four characters, Oppenheimer is the one I feel the most empathy for, but he’s also the one I pity the most.

CONCLUSION:

I think the nature of the character interaction in this novel makes it a delight to read. What could have been a dry or even boring subject comes across as enthralling and exciting, not to mention highly amusing at times. Thoroughly entertaining, I guarantee that much.

Last but not least, the “one impossible thing” allowed to SF writers per individual work shows up late in the novel as the perfect solution to the ultimate threat facing the human race, not to mention granting Oppenheimer a satisfying resolution to his life. It lifts the novel from alternate history into the realm of bravura science fiction extrapolation in keeping with the most daring SF concepts offered in the past. Very, very cool. Took me totally by surprise. Nevertheless, it works. Strikes me as entirely appropriate. Wonderful conclusion to a wonderful book.

Check it out at: < The Oppenheimer Alternative >