A metal sphere hovers over a barren lunar landscape, with a dimly-lit Earth visible in the background. What is this contraption? A vehicle, or some kind of artificial satellite? Did it originate on Earth, on the Moon, or somewhere else entirely? And what is that greenish aura that surrounds the metal globe?

A metal sphere hovers over a barren lunar landscape, with a dimly-lit Earth visible in the background. What is this contraption? A vehicle, or some kind of artificial satellite? Did it originate on Earth, on the Moon, or somewhere else entirely? And what is that greenish aura that surrounds the metal globe?

It was February 1928, and Amazing Stories was taking its readers on another trip to worlds unknown.

This month, Hugo Gernsback’s editorial is given over to an announcement: in response to the numerous readers who had asked for Amazing to be published more than once a month, the magazine was soon to receive a sister title, Amazing Stories Quarterly. Gernsback goes on to list the stores that will appear in the debut issue of Quarterly, including a complete reprint of H. G. Wells’ novel When the Sleeper Wakes.

But such matters lie in the future. For the present, let us content ourselves with the latest batch of stories from the original, monthly incarnation of Amazing Stories…

Baron Münchhausen’s Scientific Adventures by Hugo Gernsback (Part 1 of 6)

Hugo Gernsback wrote a total of three novel-length stories; Baron Münchhausen’s Scientific Adventures was the first of these, and was serialized in Electrical Experimenter magazine from 1915 to 1917. With this issue, Amazing begins reprinting this work with the first of six installments – or, looking at it another way, the first two of thirteen installments.

Hugo Gernsback wrote a total of three novel-length stories; Baron Münchhausen’s Scientific Adventures was the first of these, and was serialized in Electrical Experimenter magazine from 1915 to 1917. With this issue, Amazing begins reprinting this work with the first of six installments – or, looking at it another way, the first two of thirteen installments.

The first of these episodes is “I Make a Wireless Acquaintance”. After introducing himself as the son of cactus and ostrich-farmers who arrived on the Mayflower, narrator Ignaz Montmorency Alier lists his technological accomplishments. He pioneered a wireless mousetrap, which would trap rats in rotating cages and send radio signals to HQ, whereupon Alier’s employees would travel to the home in question and kill the rat, thereby saving the homeowner this unpleasant task. I. M. Alier has since moved on from this endeavour, and now operates the only long-distance radio telephone station in the United States.

One night, Alier receives a radio message from someone purporting to be a resident of the Moon named Hieronymus Karl Friedrich, Baron Münchhausen. Alier dismisses this as a prank, only for Münchhausen to prove the truth of his words by illuminating the surface of the Moon with a light visible from Earth. The Baron explains that he faked his death in 1797, but his fakery was a little too successful, and he was duly injected with an embalming fluid that left him unconscious until 1907, when he woke up in a rejuvenated frame.

The second episode, “How Muenchhausen [sic] and the Allies Took Berlin”, sees the Baron continue his life story. He describes how, facing persecution from German authorities due to political outrages he committed more than a century beforehand, he migrated to Paris and took up scientific research. During the First World War, he pioneered the use of such ingenious yet bloodless projectiles as cylinders of laughing gas, lumps of itchy salt and immobilizing cables to drive the Germans into their trenches. He then became responsible for a tremendous mix-up: his ingenuity allowed the Allies to take Berlin, but at the cost of allowing the Germans to take Paris. This confusing state of affairs was the subject of a large-scale cover-up, and did not reach the media.

After this, the Baron describes his invention of a “gravity insulator” which works by neutralizing luminiferous ether. Using this, he was able to reach the Moon in a spherical steel craft. His communication with Alier than breaks off before he can outline his further exploits.

In contrast to his second novel, the rather dry Ralph 124C41+, Baron Münchhausen’s Scientific Adventures combines Gernsback’s love of gadgetry with a hearty sense of humour. It is interesting as an early work of science fiction that continues the exploits of a character from a still earlier era of imaginative fiction.

The Master of the World by Jules Verne (Part 1 of 2)

Having completed its reprint of Verne’s Robur the Conqueror, Amazing begins serializing the novel’s 1904 sequel.

Having completed its reprint of Verne’s Robur the Conqueror, Amazing begins serializing the novel’s 1904 sequel.

The story opens with great rumblings emanating from a North Carolina mountain, sending the locals of nearby Morganton into a panic about impending volcanic eruption. The authorities send police inspector John Strock to investigate; he climbs the mountain but fails to find an entrance.

Strock later finds himself the target of strange attention. He receives a mysterious letter, the author identified merely as “M. o. W.”, warning him to make no further trips to the volcanic mountain. Two men begin lurking outside his house, as though spying on him.

Meanwhile, multiple sightings occur of a mysterious car travelling along American roads, with no discernible means of propulsion and yet running so fast as to inspire rumours that it is driven by the Devil himself. Next, an apparent sea monster is sighted off the New England coastline. John Strock sees through this talk of devils and monsters, and speculated that the two phenomena have a single cause: a machine capable of travelling on land and in sea. This idea catches on following reports of more phenomena, a submarine apparently joining the mysterious car and boat.

Various governments offer vast sums of money to the mysterious inventor, but the self-identified Master of the World issues a statement turning them down. Strock realizes that this must be the “M. o. W.” who sent him the previous letter, and embarks on a mission to find the elusive inventor.

The Master of the World was the final Jules Verne story to run in Amazing under Hugo Gernsback’s editorship.

“The Fourteenth Earth” by Walter Kateleny

An examiner at the Patent Office, while sorting through the latest batch of applications, comes across a document describing a method of altering the atomic density of any given matter using a substance that it refers to as Transite. Intrigued, the protagonist decides to visit the author of this application – only to find that the scientist, named Kingston, has gone missing.

An examiner at the Patent Office, while sorting through the latest batch of applications, comes across a document describing a method of altering the atomic density of any given matter using a substance that it refers to as Transite. Intrigued, the protagonist decides to visit the author of this application – only to find that the scientist, named Kingston, has gone missing.

The patent examiner then visits Kingston’s laboratory and, after unwisely fiddling with a certain device, begins rapidly shrinking. His atomic density has been altered, taking him to a new world: “I decided that the hardness or density of the things of this surface must bear about the same relation to the density of the next stratum above, as our common earthly things do to the stratum that we call air; and it occurred to me that what I was breathing might be a great many times more solid than granite rock.”

The minute world is populated by people as tiny as the reduced protagonist. One member of this race, Akon, explains the workings of his civilization, including their adherence to a religion based upon scientific evidence. The narrator is surprised at the simplicity of the people’s belief system, but then concludes that terrestrial religion may reach a similar state thousands of years in the future; after all, the extravagant sacrifices and towering temples of previous eras have already fallen out of favour.

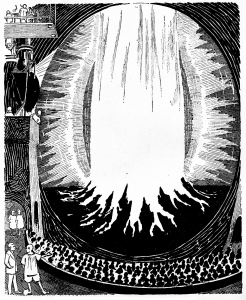

The people also have the ability to create food and other objects from primary elements. Akon takes the protagonist to see this process, which has a spectacular by-product: gases fly into the sky as immense flashes of light, like the aurora borealis. As beautiful as the sight is, the narrator is appalled when he realizes that these subterranean fireworks are the cause of the deadly volcanic eruptions across his own world. Because the visitor had taken a piece of Kingston’s device with him, the scientists of the lower world are able to reverse-engineer this technology and return their guest back to his correct size.

By this point, Amazing had run a number of stories in which characters find new worlds not by visiting other planets, but by looking beyond the visible spectrum, entering another dimension, or drastically altering their size; “The Fourteenth Earth” is an interesting addition to this body of work.

“The Disintegrating Ray” by David M. Speaker

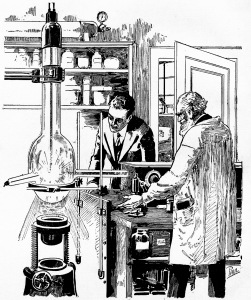

Professor Clinton Wild invites a student to his laboratory to witness a new invention. The professor explains that his creation is a modified X-ray device, one capable of disintegrating atoms, thereby altering substances on the elemental level:

Professor Clinton Wild invites a student to his laboratory to witness a new invention. The professor explains that his creation is a modified X-ray device, one capable of disintegrating atoms, thereby altering substances on the elemental level:

“You see,” said the professor, “that my ray, which from now on I will refer to as the epsilon ray, is composed of a stream of electrons vibrating at a high frequency. When this ray is directed toward a substance, it penetrates each atom. The electrons, of the ray meet the electrons in the atom and there is a collision, which results in the atom losing some of its electrons. This loss changes the identity of the substance.”

Professor Wild then demonstrates his invention by turning mercury into gold, after which he reveals that he has used his epsilon rays to produce previously undiscovered elements. He outlines how his invention could bring about both apocalypse and utopia: on the one hand, unless sufficient precautions are taken, the disintegrating effect of the rays could easily spread across the entire world, destroying it; on the other, the rays can provide limitless atomic power. He then dismisses the student – who later reads in a newspaper that Professor Wild has been killed as a result of his invention exploding.

With the thinnest of narratives, “The Disintegrating Ray” is really more an outline of a hypothetical invention than a story. David M. Speaker’s vision of atomic power makes for an interesting contrast with the real thing.

“The Revolt of the Pedestrians” by David H. Keller

This story opens with a woman being run down by a car:

This story opens with a woman being run down by a car:

The lady in the sedan was annoyed at the jolt and spoke rather sharply to the chauffeur through the speaking tube.

“What was that jar, William?”

“Madam, we have just run over a pedestrian.”

“Oh, is that all ? Well, at least you should be careful.”

“There is only one way to hit a pedestrian safely. Madam, when one is going sixty miles an hour and that is to hit him’ hard.”

“William is such a careful driver,” said the Lady to her little daughter. “He just ran over a pedestrian and there was only the slightest jar.”

The little girl looked with pride on her new dress.

The reason for this callous response to the vehicular homicide is that the story takes place in a future where motorists and pedestrians have split into two distinct strains of humanity. The former have become so reliant on their vehicles that their legs have atrophied; amongst parents, it is a badge of pride that their children have never walked. The latter, meanwhile, are viewed by motorists as something subhuman, “perhaps higher than apes, but much lower than automobilists”, their rights having degraded to the extent that it is not only legal to run down pedestrians – it is actively encouraged by the government. The few remaining pedestrians escape this attempted extermination by retreating into the wilderness, where they plot their revolt…

Heisler, a man who hails from an influential family of aristocrats, has a dark secret: his only child, Margaretta, can walk. Research reveals that a hundred years ago, the Heisler family intermarried with a clan of revolutionary pedestrians called the Millers, and Margaretta is a throwback to the Miller line. As she grows, she picks up such strange habits as reading by candlelight and enjoying nature.

Eventually, the pedestrian revolutionaries perform their masterstroke: they activate a device that eliminates the autoists’ electricity. Society is brought to a standstill and the autoists begin dropping like flies, their atrophied legs preventing them from obtaining food without machines to help them. Before long, the world once again belongs to pedestrians like Margaretta.

“The Revolt of the Pedestrians” is a Swiftian satire that touches upon a number of themes. It comments on economics, depicting a socialistic society that “provided comfort for the masses but had singularly failed to provide happiness”, instead supplying them with uniform buildings, concrete furniture, identical clothes made from waterproof furniture, and food sold as blocks of nutrients. The story addresses ecology by establishing that the atmosphere of the future is polluted by “the dangerous vapors generated by the combustion of millions of gallons of gasoline and its substitutes”; and as the motorists no longer work, they no longer sweat, which prevents the toxins from leaving their bodies.

The persecution of the pedestrians has parallels to the US government’s persecution of the Native Americans – although the story’s two direct reference to indigenous tribes are very stereotypical, as the Natives of the future live in wigwams and are prone to killing people who enter the wilderness.

Read today, “The Revolt of the Pedestrians” is an intriguing piece of satire, some of its comments being dated and others still relevant.

“The Fighting Heart” by W. Alexander

Tom Wilson, a man with an inferiority complex (he refers to a black train porter as “sir”, which the story uses as evidence of this trait) inherits a million-dollar estate from a dead relative. He goes to his friend Dr. Wentworth for advice: when word get s out about his wealth, how can he prevent people from taking advantage of his weak will to feed off him?

Tom Wilson, a man with an inferiority complex (he refers to a black train porter as “sir”, which the story uses as evidence of this trait) inherits a million-dollar estate from a dead relative. He goes to his friend Dr. Wentworth for advice: when word get s out about his wealth, how can he prevent people from taking advantage of his weak will to feed off him?

Dr. Wentworth suggests an exchange of hearts, a procedure which he says has recently become possible thanks to a new substance called Collodiansy, which speeds up the healing of incisions and, when used in conjunction with a new long-lasting anaesthetic, allows more sophisticated operations than before.

The doctor arranges for Tom to switch hearts with an athletic young man. He reassures his friend that the operation will not affect the second man, as there is no real problem with Tom’s heart – his problems are purely mental, and receiving the athlete’s heart will boost his self-esteem.

The effect of the procedure on Tom’s personality is extreme. At work, he beats up a bullying foreman; he then torments his boss – immediately after being offered a promotion, no less. At home, he gives his henpecking wife similar treatment (“‘Whom do you think you are talking to,’ exclaimed Tom, as he took hold of her shoulders and shook her until her teeth rattled. ‘I’ll teach you to stand around jawing instead of getting my supper'”) which eventually results in her gaining new affection for him (““All right, my love,’ cooed Ann with a happy laugh. ‘I’ll get dolled up tomorrow so you won’t know me'”). Finally, he goes to thank Dr. Wentworth – who reveals that the heart exchange never took place; it was all a ruse to boost Tom’s confidence.

“The Fighting Heart” is a sequel to W. Alexander’s earlier “New Stomachs for Old”. It is based around the same essential joke – that an organ transplant would lead to a personality switch – and is a time capsule of some rather ugly social attitudes.

“Four Dimensional Surgery” by Bob Olsen

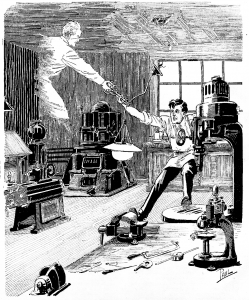

In this sequel to “The Four-Dimensional Roller Press”, inventor William James Sidelburg is still missing as a result of his creation backfiring. The narrator is Sidelburg’s former assistant, who receives a visit from world-famous surgeon Dr. Paul Mayer and the similarly renowned mathematician Professor Banning. It turns out that Banning is hoping to undergo a risky surgical procedure, which Mayer tells him has only a one in a hundred chance of success; but this risk could be lowered if the surgical instruments operated in four dimensions.

In this sequel to “The Four-Dimensional Roller Press”, inventor William James Sidelburg is still missing as a result of his creation backfiring. The narrator is Sidelburg’s former assistant, who receives a visit from world-famous surgeon Dr. Paul Mayer and the similarly renowned mathematician Professor Banning. It turns out that Banning is hoping to undergo a risky surgical procedure, which Mayer tells him has only a one in a hundred chance of success; but this risk could be lowered if the surgical instruments operated in four dimensions.

The assistant, despite his familiarity with the technology, doesn’t entirely understand the theory; but fortunately for everyone, Banning is a researcher in the fourth dimension and so can explain the ideas to protagonist and reader alike. The explanation is substantial, and comes with a diagram; it evolves from a discussion about hypothetical two-dimensional beings (likely influenced by Thomas Abbott Abbott’s novel Flatland) and then onto a conversation about a tesseract, a twenty-four-sided cube that exists in four dimensions.

The protagonist is uncertain. “I’m not superstitious exactly,” he says, “but sometimes I think that Nature resents our efforts to pry into her secrets —and punishes those who are too rash and importunate in wresting knowledge from her.” Banning has no patience for such talk: “If that were so, Thomas A. Edison, Orville Wright, Robert Milliken and hundreds of other great men would have been destroyed long ago. Sidelburg was merely the victim of an unforeseen accident.”

The narrator eventually agrees to help develop four-dimensional surgery. During the project, the assistant gets into an argument over supernatural phenomena; he suggests that spirits might exist in the fourth dimension (“‘There are more queer things in heaven and hell than were ever dreamed of in your philosophy!”) prompting a derisive response from Banning.

As the revolutionary implement (dubbed the Hyper-Forceps) nears completion, Banning’ health declines rapidly. Eventually, the new tool is put to the test, and succeeds in bypassing the walls of a bottle by entering the fourth dimension: “I was dumfounded to see the Hyper-Forceps, part by part, melt into nothingness and disappear from sight until only the handles were visible.”

After a trial operation on a goat, Mayer – clad in X-ray goggles – begins the procedure to remove Banning’s gall stones. But disaster strikes, and some unknown force causes Mayer, Banning and the Hyper-Forceps to vanish into nothingness.

The narrator heads to an adjacent workshop, and sees the head of the Hyper-Forceps appear out of thin air and cling to an electric wire. He grasps them, and succeeds in pulling the tool back into three-dimensional space – Mayer and Banning with it. After this experience, the three discuss the “mystic realms of hyper-space”, and Banning reveals that while adrift he was able to remove his gall stones with his bare hands.

This time we have a sequel that does a good job of expanding upon the basic ideas of its predecessor. Bob Olsen would go on to write three more stories of four-dimensional exploits.

“Smoke Rings” by George McLociard

Fire-fighters speed to a burning barn, where they come across a striking sight: a man willingly surrendering himself to the blaze, leaving behind him a steel box. After the fires are extinguished, the box is open to reveal the dead man’s testament.

Fire-fighters speed to a burning barn, where they come across a striking sight: a man willingly surrendering himself to the blaze, leaving behind him a steel box. After the fires are extinguished, the box is open to reveal the dead man’s testament.

In his account, the man identifies himself as Wilbur Gunderson. While serving as an anti-aircraft gunner in the war, he saw a dragonfly dart under a smoke ring blown from his cigar, and was struck with inspiration: a weapon that could down enemy aircraft by blown enormous rings of explosive gas.

Upon returning to the US, Gunderson began work on his invention. Upon completion he gave it a test, noticing only two late that an American zeppelin, the USS Shenandoah, was flying overhead in the direct path of his ring.

The airship’s destruction was officially blamed on a storm, but Gunderson’s guilt at his responsibility led to his confession and suicide.

“Smoke Rings” is a very brief story that incorporates a real-life airship disaster which occurred less than three years beforehand – making it an interesting companion piece to Gernsback’s humorous re-writing of World War I in the same issue. George McLociard decorates his short narrative with a most flowery prose style:

I came upon the scene and stopped, overcome by horror. Slowly, the realization of what I had done gripped me. I had done it! I! “You murderer!” screamed the crushed and torn framework of what had once been the pride of America. The ghastly severed girders stretched their long pointed fingers accusingly at me. I stood for hours brooding over the ruins.

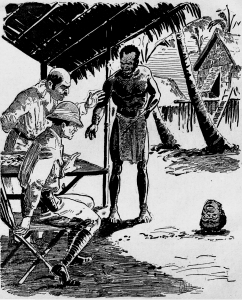

“Pollock and the Porroh Man” by H. G. Wells

During an expedition to Sierra Leone, English traveller Pollock witnesses a woman being killed by a member of the secret society known as Porroh. Pollock tries and fails to apprehend the killer; escaping, the Porroh man glances under his arm at Pollock, who catches a glimpse of the fugitive’s upside-down face.

During an expedition to Sierra Leone, English traveller Pollock witnesses a woman being killed by a member of the secret society known as Porroh. Pollock tries and fails to apprehend the killer; escaping, the Porroh man glances under his arm at Pollock, who catches a glimpse of the fugitive’s upside-down face.

By this point Pollock has already seen his share of carnage, and is also racially prejudiced; as his companion Waterhouse says, “You’re one of those infernal fools who think a black man isn’t a human being”. And so, the African woman’s death itself does not bother him. Yet, despite this, he is troubled by the feeling that the incident was just the beginning of a larger affair.

Pollock is haunted by a recurring nightmare of the Porroh man’s upside-down face; he also suffers from illness and is plagued by attacks by snakes and red ants, all of which leads him to wonder if he is the victim of a curse. Eventually, the Englishman resorts to having the Porroh man killed; the assassin brings him the man’s severed head and drops it on the floor – where it lands upside-down. Pollock’s friend, a trader named Perera, tells him that this will not save him from this curse: the only ways to break the spell would have been to either make the magician remove it, or kill the magician himself.

The Porroh man’s inverted face continues to haunt Pollock. He buries the head but wakes up in the night to find it staring at him, still upside-down, having been dug up by a dog. He throws it into the sea, only for it to wash up and be discovered by a trader – who, failing to sell it to Pollock, drops it in his shed. He places it on a burning pyre shortly before leaving by steamer; on board the boat, the captain reveals that he has found the Porroh man’s head and taken it as a curiosity. He keeps it pickled in a jar – where, for reasons unknown, it floats upside-down.

By the time he arrives back in England, Pollock has begun to suffer from a constant hallucination of the Porroh man’s inverted head. The toll on his mental state is so severe that he finally resorts to suicide.

This 1895 H. G. Wells tale is a curious choice for a science fiction magazine, as it is clearly a ghost story – albeit a ghost story ambiguous enough to be read as psychological rather than supernatural in nature. It is an affective piece of work, although its social attitudes do not stand up to close examination. While the story ostensibly criticises European involvement in Africa – through the portrayal of the crass, bigoted Pollock – Wells regrettably falls back on stereotypes of Africa as a land of witchcraft and devilry.

Poetry by Leland S. Copeland

After several months’ absence, Leland S. Copeland returns with three more poetic contributions to Amazing.

“World Unknown”

A billion stars have merged their sheen

To form a disk of light

Beyond the frigid silences

That void eternal night;

Ten million years away it looms,

A telescoping sight

The dinosaur was lord of earth,

In mesozoic days,

And neither ape nor man had life

when that vast stellar maze

Beyond the guldes of time released

The light that meets our gaze.

And lost within that universe,

Within its milky way,

How many worlds around their suns

Have woven night and day

For countless thinking things like men,

Now deep in stone or clay.

Their stories, caught in light, have come

To us unskilled to know

The comedy and tragedy,

The glint of friend adn foe,

Within this cryptic message from

A far and long ago.

“Cosmic Ciphers”

In deep of night when I awoke

There came a frank and lonely thought

That some day we should die, and all

We valued should be for us naught.

But can the Universes mourn

When transient lives like ours are done,

And we no longer walk a mote

Day-lighted by a tiny sun?

For flies that fall by human stroke

Are greater loss to Mother Earth

Than dying men to That within

The Vast where all the stars had birth.

“Ourselves”

Born of earth and sunshine,

Drawn from ages past,

You and I inhabit

Planet Three at last.

Savage, saint and thinker

Mingle in our mind;

Swayed by ancient urges,

Our wee lives unwind

Changed to light and stardust,

We at length must drift

Over void and darkness

Down a stellar rift.

Ere we travel blindly

Through the starred abyss

Seize and share the joy of

That expanse and this

Discussions

The issue’s letters column opens with a long missive from Eugene L Middleton; this is something of an ancestor to this very blog series, as it contains an issue-by-issue retrospective of the magazine. “When reading Amazing Stories,“ Middleton tells us, “I mark the stories when I finish them using marks to show how much I liked them. For instance, the figure ‘1’ means the story is good enough to merit my attention, ‘2’ is good, ‘3’ is very good, ‘4’ excellent, and ‘5’ is the highest order.”

To Middleton, Jules Verne “is always worthwhile” even if “his style is rather Mid Victorian, and comparatively hard to read in this present age.” Ray Cummings’ “Around the Universe” is good, despite being “filled with too much slang and poor language”. M. H. Hasta’s “The Talking Brain” was a “horrible” story, but these have their place: “Continue publishing horrible stories once in awhile. They can’t be worse than much of actual life.” Citing Garrett P. Serviss’ A Columbus of Space, Middleton argues that “there seems to be a kind of drag in most interplanetarian stories—the formula being almost always about the same—consisting of a weird cylinder near death from bombarding meteors etc.” Doctor Mentiroso, meanwhile, “seemed not so much to be a Ph.D as a D——- Ph——!”

Middleton is not kind towards H. G. Wells. “In Wells’ opinion, all the rest of us are rotten and many of us share the same opinion regarding H. G. Wells. You just know his characters, as a rule, have halitosis and bromidrosis. They are as a rule unnecessarily mean and snobbish. His stories, instead of having the fire of enthusiasm such as we find in those of Verrill are slow and plodding and plain British ‘stodgy.’” The letter argues that Wells is inferior to the relative newcomer H. P. Lovecraft: “if H. G. Wells could make anything as worthwhile as ‘The Colour out of Space,’ he would have something to brag about”.

“[I]m many of your stories the hero either goes insane, is killed or else disappears and is not seen thereafter”, notes F. P. Swiggett Jr. “This is especially true if the main character is an inventor… this unhappy event absolutely prevents a sequel being written to the story.” The letter goes on to chide the soldiers in The War of the Worlds for failing to use aeroplanes or gas masks. This complaint overlooks the era in which the novel was written – as a letter from an anonymous reader from Bermuda points out.

Attacks on, and defences of, H. G. Wells are a recurring theme this month. Mrs E Grunt, in a letter which Amazing titled “What a reader of the fair sex thinks of H. G. Wells”, objects to the author’s treatment: “Do you only print letters that abuse Mr Wells?” she asks. “I have been under the impression that he is to be classed with Shakespeare and Dumas and Dickens. Why, every time I read one of the letters that endeavor to criticize Mr Wells’ works, I experience a chilling shock.”

C. P. Prescott makes a similar objection: “Some of the self-appointed critics do not have the common decency to adhere to the regulations of convention in their fervor of derision, but resort to the vocabulary of the pugnacious illiterate, to express their vehemence… let us hope he successfully repels this individual onslaughts and does not deviate to the level of his disparagers’ imaginations.” Also on hand to defend Wells is Schuyler Miller, who argues that a Martian heat-ray could easily down an aeroplane. Lawrence Clark, meanwhile, lambasts Wells as “the worst writer that you have”, criticising the side-story of the narrator’s brother in The War of the Worlds.

Elsewhere, Dr. J. I. Cebra recounts trying to talk sense into a friend who dismissed Amazing Stories as “trash” (“if such men as Edgar A. Poe and H. G. Wells wrote ‘trash’ I had yet to know it”) while B. Allen Frazier continues the previous issue’s discussion about the time travel depicted in A. Hyatt Verrill’s “The Astounding Discoveries of Doctor Mentiroso”.

Watkin L. Evans critiques the magazine’s presentation (“looking at the book from the inside out, it has merit which does not reflect from the outside in”), cites Metropolis as to look towards the science fiction of Europe, and expresses ambitions to write science fiction of his own: “I hope within the next four months to submit a story similar to Garret Smith’s ‘Treasures of Tantalus’”.

“I find myself stumped when I try to interest my friends in its content”, complains Arthur Ostrander in the issue’s final letter. “Some think me crazy, some just smile in a pitying way, and others would like to be more convinced.” His slightly literal-minded proposal is that Amazing run a story set in the Middle Ages, in which people of the technological wonders of the twentieth century, thereby showing that what seems like fantasy in one era may be hard reality in another. “I am sure such a story would convince the majority of my friends of what might happen in the future.”

Read My Profile