Clad in thick fur parkas, a band of people skate across a body of ice. A short distance from them stand two icy mounds, each with a sailing boat perched uselessly on top, like relics from a bygone age. Above this scene is an oddly yellow sky, dominated by the looming form of the planet Saturn. Wrapped around Saturn’s upper hemisphere are two words of bold promise: Amazing Stories.

Clad in thick fur parkas, a band of people skate across a body of ice. A short distance from them stand two icy mounds, each with a sailing boat perched uselessly on top, like relics from a bygone age. Above this scene is an oddly yellow sky, dominated by the looming form of the planet Saturn. Wrapped around Saturn’s upper hemisphere are two words of bold promise: Amazing Stories.

The month was April 1926, and a groundbreaking new magazine had reached the newsstands.

The first editor of Amazing Stories was Hugo Gernsback, who had a background in factual magazines about radio and other forms of electronics. Here, he occasionally ran what would now be termed science fiction; one of his magazines, Science and Invention, even had a dedicated “Scientific Fiction Number” in 1923.

Gernsback himself had tried his hand at the fledgling genre with Ralph 124C 41+, a short novel that was serialised in Modern Electrics from 1911 to 1912. Set in the 27th century, the story follows the titular Ralph 124C 41+ (“one of the greatest living scientists and one of the ten men on the whole planet earth permitted to use the Plus sign after his name”) as he falls in love with the beautiful Alice 212B 423, eventually using his scientific know-how to save her from a Martian evildoer.

The thin plot serves mainly as an excuse for Gernsback to take us on a tour of an imagined future, with almost every chapter introducing us to a new technological marvel – be it anti-gravity, synthetic food or a means of projecting stage plays into living rooms. Ralph 124C 41+ comes across less as a narrative, and more as a manifesto: here is the future, now let us write about it.

With Amazing Stories, Gernsback had the opportunity to put his manifesto into practice.

“Amazing Stories is a new kind of fiction magazine!” proclaimed his editorial in the series’ debut issue. “There is the usual fiction magazine, the love story and the sex-appeal type of magazine, the adventure type and so on, but a magazine of ‘Scientifiction’ is a pioneer in its field in America.”

Gernsback defined “scientifiction” as “a charming romance intermingled with scientific fact and prophetic vision.” The pioneer of this form, the editor continued, was Edgar Allan Poe: “It was he who really originated the romance, cleverly weaving into and around the story a scientific thread.” After Poe came Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, two more authors inspired by a changing world:

It must be remembered that we live in an entirely new world. Two hundred years ago, stories of this kind were not possible. Science, through its various branches of mechanics, electricity, astronomy, etc., enters so intimately into all our lives today, and we are so much immersed in this science, that we have become rather prone to take new inventions and discoveries for granted. Our entire mode of living has changed with the present progress, and it is little wonder, therefore, that many fantastic situations—impossible 100 years ago—are brought about today. It is in these situations that the new romancers find their great inspiration.

Off on a Comet by Jules Verne

The shadow of Jules Verne looms large over Amazing Stories #1. The issue opens with line-art of Verne’s tomb, which includes a statue of the author emerging from his grave as an Olympian immortal; this image was to become an Amazing Stories icon, and even featured on the cover of the May 1934 issue. After this, Gernsback announces in his editorial that he is in talks to reprint Verne’s bibliography in its entirety. It is scarce unexpected, then, that the first story to run in Amazing was by Jules Verne; but it is perhaps surprising that Gernsback chose one of Verne’s lesser-known works: Off on a Comet, a novel originally published in 1877 under the title of Hector Servadac.

Captain Hector Servadac and his comrade Ben Zoof are traveling on the coast of North Africa when they are suddenly thrown to the ground by an enormous tremor. Recovering, they find that this was no mere earthquake: the surrounding geology has changed, leaving them on an island while the mainland has been replaced with water. Furthermore, Earth’s gravity appears to have lessened, while something very strange seems to have happened to the planet’s orbit:

“Well, I am curious to know what they think of all this at Mostaganem,” said the captain. “I wonder, too, what the Minister of War will say when he receives a telegram informing him that his African colony has become, not morally, but physically disorganized; that the cardinal points are at variance with ordinary rules, and that the sun in the month of January is shining down vertically upon our heads.”

Ben Zoof, whose ideas of discipline were extremely rigid, at once suggested that the colony should be put under the surveillance of the police, that the cardinal points should be placed under restraint, and that the sun should be shot for breach of discipline.

The two men submit themselves to becoming the Robinson Crusoe and Friday of this new land, until they are found by a ship – on which Servadac meets his old rival, Count Timascheff. Together, they travel the sea and find a few scattered survivors of various nationalities, but no sign of settlement. The men put their heads together and deduce that they are no longer on Earth, but on a fragment of Earth that has become separated from the rest of the planet, and is now taking them to unfamiliar regions of the solar system.

The story contains a satirical streak, with the various displaced Europeans showing patriotism to countries that no longer exist on the same orbital body as themselves, and squabbling over the colonial status of an island which only they inhabit. Verne clearly has fun with national caricatures: the Englishmen, for example, are such staunch traditionalists that they insist on having four meals a day even when each day is now only six hours long. Not all of Verne’s character portrayals are quite so good-humoured, however – the character of Isaac Hakkabut is a grotesque anti-Semitic stereotype.

Amazing Stories #1 prints the first half of Off on a Comet. The installment ends just as Servadac and company locate an astronomer who has deduced how they wound up in space – although the book’s English title makes it rather easy for the reader to guess in advance.

Verne’s premise, that a comet could clip into the Mediterranean and take a habitable portion of Earth with it into orbit, is wildly implausible. The novel’s English edition was forced to admit as much when its introduction (not included by Gernsback) declared that the opening and ending of the story “belong frankly to the realm of fairyland.” But despite this artistic license, the main portion of the novel works as a celebration of scientific inquiry, with the characters combining astute observation and a can-do spirit to get to grips with whatever problems are thrown at them.

“The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar” by Edgar Allan Poe

Verne, like Gernsback, portrayed science and technology as the tools of heroes. The other tales featured in Amazing Stories #1, however, tend to show a more ambivalent attitude.

Edgar Allan Poe, championed by Gernsback as the father of scientifiction, is represented in the issue by “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar”. Although typically classed as horror, this 1845 story qualifies as SF as it is based entirely around a hypothetical scientific experiment: namely, an attempt to test the effects of hypnosis upon a dying person, with the tuberculosis-ridden M. Valdemar serving as subject. At the time the story was written, medical authorities such as James Braid were giving serious thought towards adopting hypnosis – previously a fringe pursuit – as a legitimate form of medicine. Indeed, upon first publication, “The Case of M. Valdemar” was widely taken as a factual account; Poe possessed a prankish streak, and did not acknowledge that the story was fiction until sometime after it was printed.

But while Poe may lay claim to having been a pioneer of science fiction, “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar” hardly fits the utopian visions of Gernsback. The experiment carried out by the unnamed narrator results in nothing but horror: the hypnotised Valdemar repeatedly protests that he is dead; and when the trance is finally broken, his body collapses into a pile of decayed matter – rather like the passing of a later horror character, Count Dracula.

“The New Accelerator” by H. G. Wells

The third of SF’s greatest pioneers, in the estimation of Gernsback, was H. G. Wells, represented in Amazing Stories #1 by his 1901 story “The New Accelerator”. This tale follows one Professor Gibberne, a chemist bent on developing a new stimulant – “a stimulant that stimulates all round, that wakes you up for a time from the crown of your head to the tip of your great toe”. Such a drug, he theorises, would make its taker twice as fast and therefore twice as productive.

Despite his uncertainties, the story’s narrator volunteers to take the experimental drug (“If the worst comes to the worst it will save me having my hair cut, and that, I think, is one of the most hateful duties of a civilised man”) at the same time as Gibberne. At first, they notice little effect; but then they step outside, and see that the world is now running in what a modern reader would refer to as slow motion.

The two protagonists initially find this disturbing, as everyday motions such as a yawn or a wink take on a grotesque aspect when slowed down. But the men soon realise the personal benefits of their newfound speed: “it filled me with an irrational, an exultant sense of superior advantage”, says the narrator. Gibberne decides to take the opportunity to do away with his neighbour’s annoying dog, grabbing the unfortunate animal and running to a nearby cliff. He is stopped mid-dash by the narrator, who pleads that trying to run in such a state may cause his clothes to catch fire through friction.

As well as being an interesting ancestor to a now-clichéd cinematic effect, “The New Accelerator” has obvious similarities to Wells’ earlier work The Invisible Man. Both involve the creation of a drug with potential for all manner of antisocial behaviour, along with a few awkward side-effects; indeed, Gibberne and the narrator each become invisible men of a sort, as their increased speed means that the rest of the town can no longer see them with the naked eye.

But while the original Invisible Man was punished for his transgressions, Gibberne is allowed to continue with his work – even evading the blame for the unfortunate altercation with the dog. The story ends with the narrator describing, at length, Gibberne’s plans for a modified formula, one that is slightly less potent but has the same general effect. The New Accelerator may be put to criminal ends, the protagonist acknowledges, but we will simply have to wait and see what overall effect it will have on the public. Wells’ visions of the future alternated between utopia and cataclysm; “The New Accelerator” captures this overall ambivalence within a single narrative.

“The Man Who Saved the Earth” by Austin Hall

Alongside the contributions from Verne, Poe and Wells are three stories by writers who are nowhere near as well-known today, even within SF circles. One of these is Austin Hall’s “The Man Who Saved the Earth”; its author was primarily a Western writer, and reportedly wrote hundreds of stories in this genre, although these are now even more obscure than his smattering of SF works. “The Man Who Saved the Earth” originally ran in a 1919 edition of All-Story Weekly, a distinguished purveyor of pulp which, among other things, introduced the world to Tarzan.

Hall’s story begins with the narrator, in a spirit of breathless hero-worship, introducing us to Charley Huyck: the man who would sacrifice himself to save the world. Huyck lives in the twenty-first century, a period of quiet utopia which is disrupted when a chunk of Broadway is suddenly wiped out by a “tremendous force of unlimited potentiality”. When the occurrence is reported, the public – confident that they know all that there is to know about science – dismiss the unexplained phenomenon as a hoax, before finally being forced to concede its reality.

The area is subsequently hit by an unknown illness carried by a “subtle, odorless pall”, radiating from the chasm that was once Broadway. The substance appears to be a new element, or “at least something which was tipping over all the laws of the atmospheric envelope”; but whatever it is, it is fatal, and people begin dropping like flies across Oakland. A similar event then occurs in Colorado, destroying a mountain. The world starts to panic: which place will be hit next?

Charley Huyck, a man fascinated by science after discovering how to burn paper with a magnifying glass as a sixth-grader, suddenly has a spark of inspiration and sets off to save the world. Hall’s background as a Western author makes itself apparent at this point: Huyck is dashed to his destination by a taxi driver named Wild Bob, and after the two have a mishap and become stranded in the desert, they receive help from a passing pair of Native Americans.

Huyck holds the theory – a theory which, by the end of the story, is universally accepted – that humanity’s evolution is the process of Earth itself becoming conscious, with mankind functioning as its intelligence. Mars, too, has achieved an intelligence, and the destructive force that is ravaging Earth (“Not puny steam, nor weird electricity, but force, kinetics—out of the universe”) is a Martian weapon used for purposes of self-preservation. As our world is depleted by forces from above, the waters and vegetation of Mars are replenished.

Exactly how Huyck saves the world is left vague; the narrator explains that the scientist perished before he could reveal his workings to the public. All we know is that it involves elaborate lenses and beams – an extrapolation of the magnifying glass that fascinated Huyck as a boy…

“The Man Who Saved the Earth” shows the clear influence of H. G. Wells. Like many Wells stories, Hall portrays scientists as eccentric and bumbling, but ultimately heroic – despite Gernsback’s introduction, which oddly interprets Huyck as a Victor Frankenstein figure. This manifests not only in the character of Huyck, but also in the brief sequence where some anonymous scientists sacrifice their lives to warn New York of the toxic element.

But Hall does not share Wells’ clarity of vision, and instead relies on some very fuzzy concepts. The half-explored notion that humanity is the world’s consciousness seems to have been inspired by Vladimir Vernadsky’s theory that Earth’s biosphere is becoming an intelligent “noosphere”, while the story’s vision of a populated but dying mars draws upon the mistaken ideas of Percival Lowell. The destructive and poisonous new element is clearly inspired by the discovery of radium twenty-one years beforehand, although modern readers will also see it as a curious prefiguration of atomic weaponry. Apparently struggling to develop these concepts into a coherent story, however, Hall ends up falling back on a piece of science that any reader will recognise: the old trick with a magnifying glass and sunlight.

That said, Hall shows a knack for pacing, presumably something he developed while writing Western adventures. Through shifting narrative focus at key moments, he succeeds in building tension even while his descriptions of apocalyptic destruction become repetitive and dull. If nothing else, “The Man Who Saved the Earth” is historically interesting as an example of Wellsian SF being adapted for the needs of the pulp market.

“The Thing from—‘Outside’” by George Allan England

In compiling Amazing Stories #1, Gernsback was able to draw upon some of the works of “scientifiction” that he had previously published in his other magazines. George Allan England’s “The Thing from—‘Outside’” was reprinted from the April 1923 edition of Science and Invention; it will be immediately familiar to a modern reader, as its plot matches a formula subsequently used by decades’ worth of monster movies.

The story follows a group of researchers – two scientists, one of whom is accompanied by his wife and sister-in-law, and a journalist – as they investigate a snowy waste in Canada. Their guides are scared away by an unknown entity, described by the geologist Jandron as “a Thing that can’t be killed by bullets”, leaving them stranded. They come across prints apparently left by the creature, and speculate that the Thing is an alien lifeform. The scientists wax philosophical; the women are nervous; the journalist Marr, a mean-spirited sceptic, scoffs at their conversations.

England, an explorer himself, successfully evokes the feelings of isolation and pervasive threat that he must have felt on his own expeditions. He also introduces a number of intriguing questions about the Thing: Is it from another planet, or the Fourth Dimension? Does it hop on one leg, as its footprints would indicate, or is it perhaps a disc-shaped lifeform that moves by rolling? Is it a scientist itself, intending to use humans as guinea pigs?

But ultimately, the story is interested less in answering questions than in creating an air of eternal mystery, and bring up various examples of purportedly unexplained phenomena from around the world.

England was clearly familiar with the writings of the pioneering paranormal researcher Charles Fort, as he has Jandon quote from Fort’s Book of the Damned (H. G. Wells, who described Fort as “one of the most damnable bores who ever cut scraps from out of the way newspapers”, would not have approved). The presence of the alien’s tracks in the snow was likely inspired by the footprints allegedly left by Yetis, and possibly also by the so-called “Devil’s Footprints” found in Devon in 1855. Dipping into outright pseudoscience, the story acknowledges what is now known as the “ancient astronaut” theory: Jandon suggests that the Easter Island statues, “which certainly no primitive race ever built”, may have been constructed by aliens.

England leaves his mysteries unsolved. The climax pits the protagonists not against the alien, but against Marr, who has been driven mad. The Thing itself remains unknown and perhaps unknowable, while the survivors of the expedition are left with “memories crawling amid the slime of cosmic mysteries that it is madness to approach”. These concepts are remarkably similar to those used by England’s contemporary, H. P. Lovecraft.

“The Man from the Atom” by G. Peyton Wertenbaker

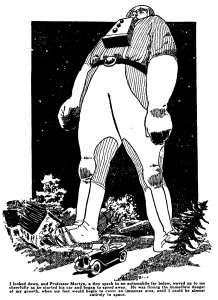

Also arriving from the pages of Science and Invention is “The Man from the Atom”, a 1923 short story by G. Peyton Wertenbaker. The main character, Kirby, is an assistant to Professor Martyn, inventor of a machine that will alter a person’s size: “you could grow forever, until there was nothing left in the universe to surpass. Or you could shrink so as to observe the minutest of atoms, standing upon it as you now stand upon the earth.”

The science behind this invention is left vague. “I have little idea of my invention except that it works by means of atomic energy”, explains Martyn. “I was intending to make an atomic energy motor, when I observed certain parts to increase and diminish strangely in size.”

Nevertheless, the protagonists are well aware of how this accidental invention could revolutionise the scientific world. “Astronomy will be complete, for there will be nothing to do but to increase in size enough to observe beyond our atmosphere, or one could stand upon worlds like rocks to examine others”, declares Kirby. Martyn then adds that “the effect of a huge foot covering whole countries would be slight, so equally distributed would the weights be.”

Donning a primitive spacesuit (which Martyn likens to a thermos bottle) Kirby activates the device and grows to titanic proportions. He outgrows Earth’s atmosphere, and witnesses “all the stars moving hither and yon”. He continues to grow and drifts away from Earth, from the solar system, and even from the universe: “Could there be nothing more in infinity than universe after universe, each a part of another greater one? So it would seem.”

As he witnesses the cosmos from ever-vaster distances, he notices the myriad universes merging together into spheres. This recurring structure reminds him of an electron – “a huge electron composed of universes”. The very idea strikes him as “terrible in its magnitude, something too huge for comprehension.” He then sees these electrons merge into molecules as he continues to grow.

Kirby’s existentially terrifying voyage ends when he finds himself in a body of water on an alien world, the macro-planet that encompasses the electron containing Earth. He pushes a button on his machine and shrinks back down, arriving by chance in the vicinity of the Milky Way. But too late he realises that, by altering his size, he had also altered his relation to time: “time is relative, and depends upon size. The smaller a creature, the shorter its life… Because I had grown large, centuries had become but moments to me.” By the time he regains his normal size, trillions of years have passed and Earth’s sun has died. He is left stranded on an unknown planet.

Its physics are rather suspect, but in all fairness, “The Man from the Atom” is not meant to be taken in entirely literal terms. The premise of this short story seems an excuse to portray the workings of atoms and electrons in a piece of narrative fiction; Kirby’s plight, meanwhile, acts as an allegory for the place of humanity in an infinite universe.

Along the way, Wertenbaker plays with a number of ideas that were put to better use by later authors. With its first-person account of an ever-faster trip through time and space, “The Man from the Atom” prefigures the novels of Olaf Stapledon, the first of which was published four years after Amazing debuted. Meanwhile, the cosmic horror felt by poor Kirby has something in common with the themes explored by Lovecraft well into the 1930s. Come the 1960s, the rise of psychedelia meant that vision quests of the kind described in this story were very much in vogue. Finally, the fanciful mechanics of Kirby’s shape-changing ability were adopted by superhero writers in creating Marvel’s Ant-Man and DC’s Atom.

For context, it is worth mentioning that Wertenbaker was born in 1907; he was fifteen when he wrote “The Man from the Atom”, and still a teenager when it was reprinted in Amazing Stories. Poe and Verne represented earlier generations of SF talent, but Wertenbaker was at the younger end of a new generation, one ripe to be utilised by Hugo Gernsback.

In its first instalment alone, Amazing Stories gave readers an overview of the ideas that Gernsback’s beloved “scientifiction” could convey. The debut issue depicted scientific inquiry variously as a means of survival, a thing of wonder, and a Pandora’s box. It showed threats posed by Martian attackers, invisible men, and beings that existed beyond known science. It introduced readers to a world in which scientists – sometimes heroic, sometimes misguided, but always brilliant – guided humanity’s destiny.

But the amazing stories were only just beginning…

Read My Profile