Rollerball is a science fiction film from 1975, made by MGM and starring James Caan (hot off The Godfather), John Houseman, Maud Adams and John Beck. It was written by William Harrison from his own short story, ‘The Rollerball Murders’, and directed by Norman Jewison, best known for the Best Picture Oscar-winner In The Heat of the Night (1968). It is set in 2018, as imagined from the mid-seventies, a fictional version of our very near future. One in which you are not reading this on the internet.

Rollerball is a science fiction film from 1975, made by MGM and starring James Caan (hot off The Godfather), John Houseman, Maud Adams and John Beck. It was written by William Harrison from his own short story, ‘The Rollerball Murders’, and directed by Norman Jewison, best known for the Best Picture Oscar-winner In The Heat of the Night (1968). It is set in 2018, as imagined from the mid-seventies, a fictional version of our very near future. One in which you are not reading this on the internet.

Rollerball was one of the wave of dark, politically aware SF films – others include Soylent Green and Invasion of the Body Snatchers – which tended to define the genre in Hollywood before the influence of Star Wars swapped cultural commentary for nostalgic fun.

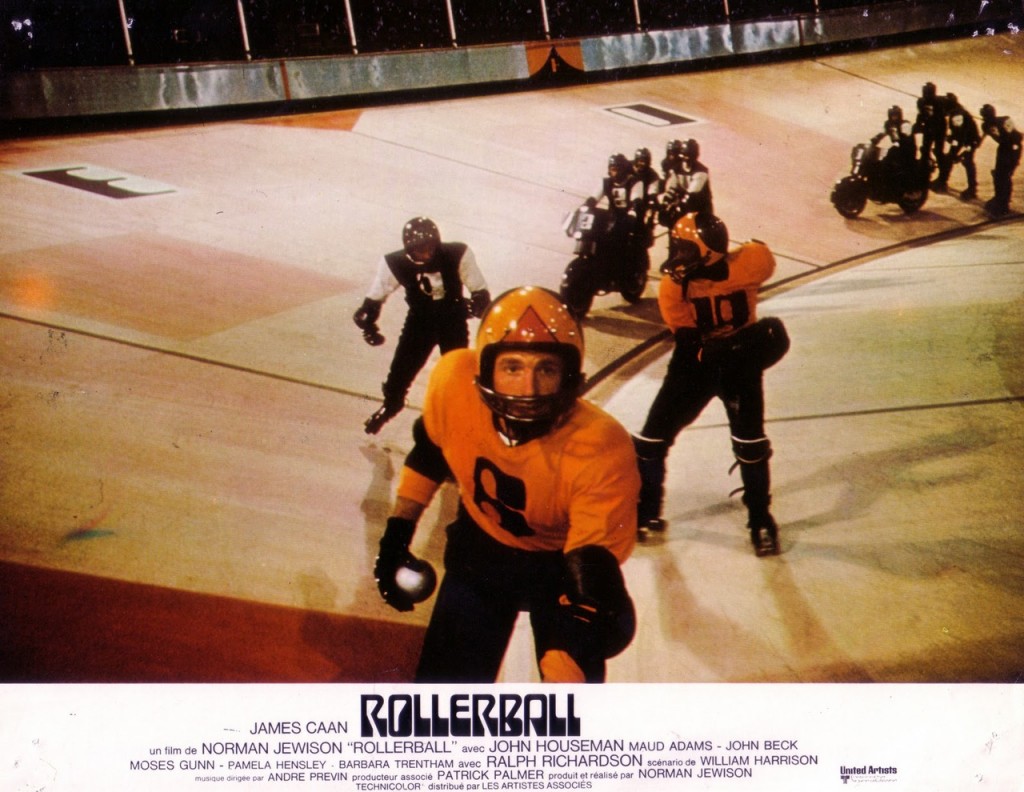

The nation state has withered away. In a nod to 1984 older people remember a time, before the Corporate Wars, when there were still three countries. Now six giant corporations rule the world, each holding a monopoly over either Energy, Food, Housing, Transport, Communications or Luxury, as well as running individual cities. War has been abolished and been replaced by the titular sport, a violent Frankenstein’s monster bolted together from track cycling (but on motorbikes), rollerskating, basketball and (American) football. It is a brutal sport with a high turnover rate, one designed to be an outlet for the masses while promoting the corporate over the individual. As one character says late in the film, ‘Game? This wasn’t meant to be a game. NEVER.’ In this secular future rollerball is the opium of the masses, though the film turns Marx on his head, suggesting not the inevitable triumph of the proletariat, but the ultimate victory of a strain of fascistic capitalism.

The story follows the Houston team, picking them up three games from the end of the season. The anti-hero is Jonathan E., a thoughtful thug who is Houston’s best player. A player who is too good, becoming too popular, too much of an individual icon. His success brings him into conflict with the powers that be, who want him to retire gracefully into a life of luxury. Articulating no good argument against doing so, even as he comes to fully understand the hollow nature of his profession, he is driven by a stubborn machismo, a largely unspoken camaraderie with his fellow players, notably the fierce but affable ‘Moonpie’, played with easy charm by John Beck. Jonathan’s team number is 6 – a tip of the hat to The Prisoner – and like Number 6 he rebels not because he is a rebel by nature, but because there is nothing else left to do if he is to retain his integrity.

The irony is that in his determination to stand loyally by his teammates, despite the corporate powers threat to change the rules of the game to make it essentially a gladiatorial fight to the death if he does so, Jonathan effectively dooms his posse. So as the film anticipates both the economic critique of Fight Club and that film’s insight into men using violence to express their frustrations with a dehumanizing system, it also looks back to the honourable, vainglorious machismo of the Western, by 1975 a dying genre, the Huston team going out in a blaze of meaningless glory which sets them in the linage of Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969). Elsewhere the film explores issues of media control and manipulation which became the central theme of its near contemporary, Sidney Lumet’s Network (1976).

All this is extrapolated through a cold, starkly designed SF landscape, the style very much in thrall to Kubrick, from its subject matter of man against an uncaring system, to the clean, minimal production design and classical music derived soundtrack, all of which evoke the detached, clinical Kubrick of 2001: A Space Odyssey and A Clockwork Orange. Again following 2001, Rollerball is an early example of what has now become conventional, a major Hollywood SF film without opening credits.

Rollerball is an action movie. There are three terrific action set-pieces in the rollerball arena, filmed in a real, purpose built full size set in Germany. But action and spectacle – all achieved through ridiculously dangerous, and brilliantly shot and edited, stunt work – are not the point, but the lure. By current standards there really isn’t much action at all. Perhaps 20 minutes in a two hour film. Rollerball dates from an era when it was still the norm, not the exception, for action movies to be about something other than action, to actually have a vision. And Rollerball’s vision is essentially about the use and abuse of power.

Ostensibly, Rollerball is one of the most brutal, in all senses, critiques of unrestrained capitalism ever made by a Hollywood studio – and we are all aware of the irony of a capitalist company making an anti-capitalist film (Rollerball, the film, was, at least in the UK, a huge hit) – but below this surface (which itself lies below the surface of a sports film) the real subject is the wielding of power. Who has it, who doesn’t, how it is used, to what ends. We know that with great power comes great responsibility, and in Rollerball unlimited power resides in a corporatocracy which has slid into dictatorship.

Ostensibly, Rollerball is one of the most brutal, in all senses, critiques of unrestrained capitalism ever made by a Hollywood studio – and we are all aware of the irony of a capitalist company making an anti-capitalist film (Rollerball, the film, was, at least in the UK, a huge hit) – but below this surface (which itself lies below the surface of a sports film) the real subject is the wielding of power. Who has it, who doesn’t, how it is used, to what ends. We know that with great power comes great responsibility, and in Rollerball unlimited power resides in a corporatocracy which has slid into dictatorship.

But Rollerball is both a science fiction film and a sports movie. Sports movies are one of the most formulaic of all genres, essentially having one plot – the underdog comes from behind and wins against all odds – and so are almost without exception predictably tedious. The few good sports movies – Somebody Up There Likes Me, Raging Bull – tend to excel as character study, or employ sport as a metaphor for something more important than knocking a ball around.

Rollerball bucks the formula, refusing to cop out on the understanding that its central sport is not worth winning, other than to make a point about who holds the power. Unlike, say, Any Given Sunday, which spends over two hours mercilessly dissecting the corruption of (American) football and the ruthless way it uses, chews up and spits out players, only to hypocritically deliver a fan pleasing underdog-comes-from-behind finale in complete contradiction to everything which had come before, Rollerball understands that it’s sport is mean, that it glories in ‘punching faces in’, that it is the modern Roman gladiatorial arena, that to celebrate winning would be to condone everything that the film is against. And so Rollerball goes against the grain of the sports movie narrative, deconstructing the game itself, changing the rules, stripping it to essentials, match by match, until the fundamental will to power is laid bloody and naked. Rollerball doesn’t just break the sports movie playbook, it understands that the rules are meaningless, and so it tears them to pieces and beats them to bloody pulp. The sports movie itself, and in the blood-thirsty baying crowd, sport itself, becomes complicit, a tool for power to manipulate and destroy, divide and rule. All of which insight, powerfully dramatised, is enough to make Rollerball the greatest sports film ever made. Not that there is much competition.

*

Rollerball may seem uncannily prophetic in a post-communist world in which 90% of American media is controlled by just six conglomerates, in which corporations draft the laws which nation states enact, in which the Trans-Pacific Partnership allow corporations to sue governments in secret courts for passing laws which impact their bottom line. The Corporate Wars are going on right now, barely noticed, with the real battle being fought between nations and multinationals, those we elect to serve and protect our interests too often being semi-secret quizlings.

But science fiction is only incidentally prophetic. Rollerball completely misses the computer revolution. Though it does suggest a world in which few read (giant TVs are everywhere) and all remaining copies of physical books are kept in a few locations, censored electronic versions being more easily available, but then only from a limited number of venues.

And while Rollerball might be taken as powerfully anti-capitalist, the capitalism it depicts is an extrapolation which – though the film does not show us how the masses live – has as much in common with 1970s Soviet or Chinese style communism as 1970s free enterprise. The deeper implication is that extreme left and extreme right eventually meet in essentially the same place. That in a secular, atheistic society, whether capitalist or socialist – there is no evidence of any form of religious belief or worship surviving in the future depicted in the film – where the only measure of value, including the value of human life, is economic, then life itself becomes nothing but a commodifiable asset to be used and discarded by those who hold the power.

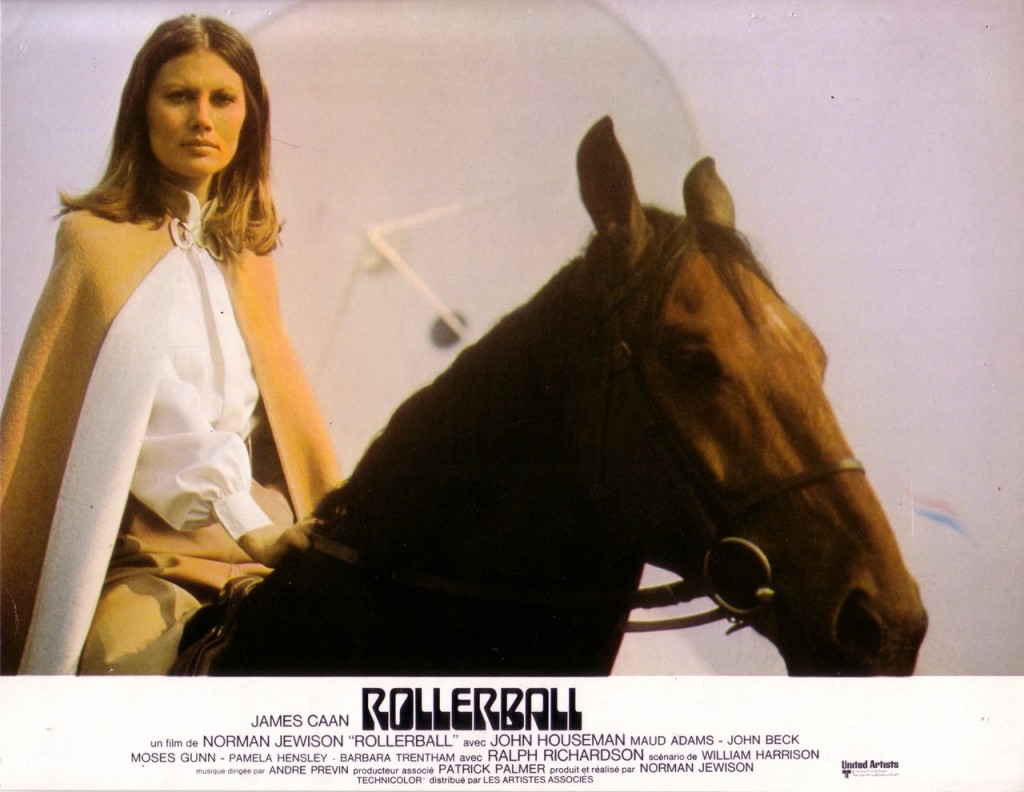

Natural then that the film focuses on the elite – they are the only ones that matter – from the players upward to the corporate executives. Here the great stage actor John Houseman comes into his own as the intellectual foil to Caan’s action man. Chilling in his sociopathic charm, so well-spoken and elegant, he might be British. Indeed, his is the villain role Hollywood normally reserves for distinguished British actors. We see the elite at play, at party, taking drugs, the players being provided with female companions somewhere between wives and, literarily, corporate whores. This dystopia is as rottenly sexist as it is corrupt in every other respect. In one shocking scene six trees are incinerated for mindless fun, the sort of vandalism Alex and his droogs might have enjoyed, here showing the utter lack of concern for anything beyond instant gratification that can come with all the isolation that power can buy. As director Norman Jewison says on his commentary track:

“Here is a scene where I wanted to devise something that would demonstrate the lack of morality, the lack of any kind of sensitive protection of something that was… that was alive and could be destroyed… a tree like this would take maybe 125 years, 150 years of life, and you will see it destroyed in an instant. Which is a warning I was trying to give of the lack of understanding of certain forces in the world that had no respect or little respect for the environment and living things, and where that would lead to because the greed of man indeed is destroying forests all over the world and as these few are left it gave us an opportunity to show that for fun and sport they would destroy a living thing in an instant.” (No living trees were destroyed for the filming of the scene).

Let’s forget the abysmal 2002 remake. Rollerball isn’t perfect. A silly sequence in Geneva, complete with hammy guest turn from Ralph Richardson, seems to have wandered in from another, far inferior film. Despite being set largely in and around Houston, Texas, Rollerball was is obviously filmed in Europe and makes little attempt to pretend otherwise. Caan’s ranch is clearly located in a verdant English landscape. Which incidentally further connects the film to Kubrick, who similarly attempted to pass off parts of England as America in Full Metal Jacket, again with little real effort put into the deception.

Let’s forget the abysmal 2002 remake. Rollerball isn’t perfect. A silly sequence in Geneva, complete with hammy guest turn from Ralph Richardson, seems to have wandered in from another, far inferior film. Despite being set largely in and around Houston, Texas, Rollerball was is obviously filmed in Europe and makes little attempt to pretend otherwise. Caan’s ranch is clearly located in a verdant English landscape. Which incidentally further connects the film to Kubrick, who similarly attempted to pass off parts of England as America in Full Metal Jacket, again with little real effort put into the deception.

There are even shots during the Rollerball games themselves when the stadium is empty of any spectators, who can then be seen cheering and screaming wildly in other sequences.

But these are minor matters. The seemingly cold film is driven not by the violence on track, but deep passion, by Jonathan’s enduring love for his lost wife, by the filmmaker’s hatred of the world they depict. In the early 70s William Harrison saw sport becoming ever more aggressive in the pursuit of ratings. Even at the time some, including some of the stuntmen who worked on the film, proposed making the fictional sport into a real world game. Thus entirely missing the point – though to the filmmaker’s eternal credit the game is coherently worked out, not just at the level of rules, but with fully thought-through playing styles for each team as well as individual strategies for the different players. The terrifying thing is, rollerball would work as a sport, and there are probably plenty of people who would pay to see a bit of the old ultra-violence.

For now we have cage fighting, photo-realistic bloodbath computer games, and violent team sports coming to be thought so important that sometimes the football coach is the highest paid member of staff on campus. This winter will see the release of the third of four films based on The Hunger Games, surely the modern teen-friendly franchise version of Norman Jewison’s modern classic. Post fall of communism, with governments subservient to corporate paymasters, Rollerball seems like a much greater, more prescient, film now than the one I originally saw back in 1976. Today Rollerball surely stands as one of the most underrated films of the 1970s and one of the most thought-provoking and rewarding SF films ever made.

For now we have cage fighting, photo-realistic bloodbath computer games, and violent team sports coming to be thought so important that sometimes the football coach is the highest paid member of staff on campus. This winter will see the release of the third of four films based on The Hunger Games, surely the modern teen-friendly franchise version of Norman Jewison’s modern classic. Post fall of communism, with governments subservient to corporate paymasters, Rollerball seems like a much greater, more prescient, film now than the one I originally saw back in 1976. Today Rollerball surely stands as one of the most underrated films of the 1970s and one of the most thought-provoking and rewarding SF films ever made.

About the Blu-ray

(Note: the stills in this post are for illustration only. They do not come directly from the Blu-ray, as despite repeated attempts my PC refused to load the disc. It plays perfectly in my Panasonic Blu-ray player.)

Twilight Time has released Rollerball on Blu-ray in the United States in a limited edition of 3000 copies. The disc is Region Free.

Technical

Rollerball is transferred in the original theatrical aspect ratio of 1.85-1. The 1080p image looks fantastic. The opening shot may come as a shock, as the image is initially very grainy indeed. This however is due to low light shooting on 1970s film stock, and once the image brightens it looks superb. Thereafter there are only a handful of darkly lit, grainy shots in the remainder of the film, and the disc presents them the way they have always looked. There is nothing wrong with that.

The film can be listened to with the original soundtrack presented in 2.0 DTS HD Master Audio. It sounds excellent, though obviously lacks the surround aspect modern audiences expect. This is catered for with an alternative 5.1 DTS HD Master Audio remix, presumably based on the 5.1 mix previously heard on the UK and Australian SE DVDs. This remix is tasteful, with so far as I could tell, no modern sounds added to boost impact, and with the emphasis on ensuring the dialogue clearly audible at all times.

Extras

Although most of the extra content has not been made specifically for this Blu-ray release, the majority of it will be new on disc to American audiences, several of the most important extras previously only appearing on the UK and Australian special editions of the film. These are:

Return to the Arena: The Making of Rollerball (25.04) a retrospective documentary made in 2001, which features interviews with many of the major cast and crew. This follows the standard retrospective making-off documentary formula and is good, if rather short.

From Rome to Rollerball: The Full Circle (7.53) is a promo documentary from the initial release of the film, which as the title suggests makes explicit parallels between the gladiators of ancient Rome and (then) contemporary society.

Commentary tracks by Norman Jewison and William Harrison. I have not listened to these in full, and the Harrison track appears to be scene specific with a fair amount of silence, but they offer a wealth of insight.

Other audio options include an isolated score track. The music is by the highly distinguished composer and conductor André Previn, though for this particular film his duties largely consisted of adapting various classical works, one of several aspects of Rollerball which show the film to be in thrall to Kubrick and 2001: A Space Odyssey. The music is brilliantly performed by the London Symphony Orchestra and Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor here serves a comparable function to the Richard Strauss which opens the Kubrick masterpiece.

Also included is the original US theatrical trailer, three vintage TV spots, which are essentially different length edits of the same material, an MGM 90th anniversary trailer the Twilight Time catalogue.

There are no foreign language subtitles, but English subtitles for hard of hearing are provided. The package is rounded off with a short but insightful booklet essay by Twilight Time stalwart, Julie Kirgo.

*

Rollerball can be purchased exclusively via Screen Archives.

Recent Comments