From a participant in two of the HiRISE teams Moses Milazzo brings some of his experience in planetary exploration, as well as some unique photographs, to Amazing Stories.

Dianne Lynne Gardner for Amazing Stories: How did you first get introduced to planetary science?

Moses Milazzo: I grew up in a large family on a small, off-the-grid ranch in the high desert of northern Arizona, near the Navajo Reservation.

While in college and trying to decide what I wanted to do with my life, I worked part-time as a student employee at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) doing computer support and data processing for the scientists at the Branch of Astrogeology. This group was helping NASA to explore a number of Solar System bodies, including Venus, Mars, and Jupiter.

When I decided to move to Tucson and finish a mathematics degree at the University of Arizona, my boss at the USGS was kind enough to put me in touch with several potential employers in Tucson and I was offered a job at the Planetary Image Research Laboratory (PIRL) processing images taken by the Galileo spacecraft exploring the Jovian system.

This job and the people in the lab stoked my interest in planetary science, and I chose to minor in the topic.

After finishing my BS, I started a Ph.D. in Planetary Sciences. My dissertation topic was, “Remote Sensing of Thermally Induced Activity on Io and Mars.”

This is a stuffy way of saying I was using our understanding of Earth’s and Io’s volcanic activity to help calibrate our search for any sort of thermal activity on Mars. If Mars currently has active magmatic, volcanic, or other thermal systems, then the potential for life on the planet increases greatly. The results of my research were that we didn’t (and still don’t) have the thermal imaging systems in orbit to say for certain that there is no internally-generated thermal activity on Mars today.

Just before I finished my dissertation, my advisor was selected to lead a new team in developing and operating a high-resolution camera to be included with a new mission sent to orbit at Mars. I was invited to participate in this, and once I had defended, I became a post-doc member of the HiRISE (High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment) camera team operating the camera on the MRO (Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter) spacecraft.

ASM: Are you, were you a fan of SF?

MM: Absolutely. In fact, I’ve been trying to branch out of science fiction because I suspect that by mostly reading SF I’m missing out on a lot of great writing.

ASM: What was your involvement in the Mars project? What exactly did you do?

MM: MRO is actually one of five currently active missions to Mars, and the HiRISE camera is one of six main science instruments on the spacecraft. I participated in two of the HiRISE teams: camera calibration and instrument operations.

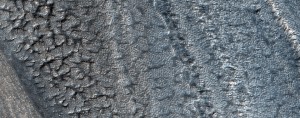

On the operations team (we had cool the title of “Targeting Specialist”), we communicated with the many scientists on the HiRISE team to help choose targets on Mars to photograph, choosing the best imaging parameters to enable science for the targets, working with the other spacecraft instrument teams to integrate all of our respective observations into one workable plan, and analyzing the quality of the imaging.

On the calibration team (we didn’t have a cool name for the calibration team, sadly), we used the science images as well as a whole slew of calibration-specific images (images taken in the dark, taken before the spacecraft launched, taken during the trip from Earth to Mars, etc.) to better understand how the camera responds to light so we could use the brightness values within the images to do better science.

ASM: This project must have been a really awesome experience. How did you approach your work emotionally?

MM: I have been incredibly lucky to have participated in all of the missions I’ve been a part of. It’s always been hard work with long hours (a spacecraft doesn’t go to sleep at 5:00 PM MST, after all), sometimes devastating losses of science due to instrument or spacecraft failures, and frustrating interactions between scientists, engineers, managers, and funding agencies. This is simply the nature of doing something so amazing and technically challenging.

But, I’ve also chosen to stay up at all hours waiting for the data to download from the spacecraft to the processing centers. I have been privileged to be the very first human to see some parts of our Solar System.

My mind boggles at my luck and privilege to have been born in a time and place that it’s possible for us to perform these amazing feats of science and engineering, and that it’s possible for me to participate in such feats. Who would have thought that a punk boy growing up in poverty on the reservation, in the middle of nowhere would fall into such a wonderful career?!

Whenever I have the time, I just sit back in awe and marvel at our ever-growing knowledge of the universe and wish everyone would have the luck to be born in this country at this time of our exploration of the universe.

ASM: You have a grasp of outer space that few others have had the opportunity to experience. Describe your thoughts about the universe in layman’s terms in a paragraph if you can.

MM: In a paragraph!? Okay, I’ll try.

The universe is insanely big. And insanely old. Anyone who thinks they can understand its size and its age on an intuitive level is fooling themselves.

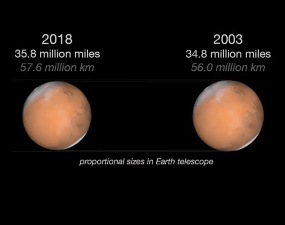

Let’s think about a long distance in human experience: driving from Chicago to Los Angeles: 2,000 miles. Now, consider this: To cover the average distance between the Earth and the Sun, we would have to take that Chicago to LA road trip 46,000 times. And to cover the distance from the Sun to the Oort Cloud, the source of our Solar System’s comets, we’d have to take that same trip about 2 billion times. It takes light a year to travel that distance. That’s big enough that we really cannot comprehend the distances between objects in our own Solar System, but the horizon of the observable universe is about 46 billion light years away. In terms of Route 66, we’re talking more than 90 billion billion road trips. Impossible to fully understand! And the universe itself may be a trillion trillion times larger than the observable universe.

The universe is so large that I cannot imagine that Earth is the only harbor of life. At the same time, we still have no evidence for it actually occurring anywhere else, and everything is so far apart that it’s difficult for me to imagine that we’ll ever meet intelligent beings from elsewhere in the universe.

What does all of this mean? To me, it means that we’re our only hope. This Earth is our only home, we’re our only neighbors, and we really need to figure out how to work together to take care of it, of each other, and of ourselves. I usually end my public speaking events with Carl Sagan’s “Pale Blue Dot” essay because he so perfectly put this idea into words.

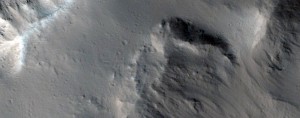

Dissected Mantle in Alexey Tolstoy Crater Rim

ASM: Do you have an interesting story to share that you experienced during the course of this project?

MM: While I was still a graduate student, I became interested in volcano-water interaction features called columnar basalts. These form via interactions with liquid water while the lava or magma is still cooling. I wrote a short conference abstract about them while the HiRISE mission was just getting started and predicted that they formed on Mars but that we probably wouldn’t be able to find them because they’re relatively small and would be difficult to see with a camera in orbit.

After a couple of years in orbit at Mars, while we were imaging the rock formations in walls of impact craters, where subsurface layers are excavated, and we fortuitously found these features. This was exciting: it means that there were times in the martian geologic past during which active lavas were interacting with liquid water near the surface.

ASM: What do you think, is there life on Mars?

MM: I fervently hope there is life on Mars, Jupiter’s moon Europa, or Saturn’s moon Enceladus. But, at the moment, we only have vague suggestions that perhaps sometime in the past there were the conditions that would support life. We have almost no evidence that suggests there is life today. This is also true of Europa and of Enceladus. We see suggestions that if life is limited to behaving like what we see on the Earth then it might be able to survive on these other Solar System bodies, but we don’t see any strong, unambiguous evidence that life is currently operating on another body. I know that’s not an answer, but without strong evidence for it, I’m afraid it’s the best I can do.

ASM: Did science fiction play any role in the career you chose

MM: I don’t remember a time when I was reading a science fiction story and suddenly, because of the story, decided I wanted to be a scientist. However, when I was about five or six, I read a history of Marie Curie and that’s when I decided I wanted to be a scientist of some kind.

ASM: What is your sense of the general population’s engagement with space?

MM: I feel that I can talk to anyone anywhere and they’ll be fascinated with what I do, but when it comes down to understanding the sciences or to funding more scientific exploration of space, there’s a disconnect. People I’ve met think we spend anywhere from 10% to 50% of the federal budget on NASA, and are stunned when they find out that it’s more like 0.5%. People seem to think we load up rockets with dollar bills and send them off to Mars when we spend $720 million on a martian orbiter, but all of that money is spent on jobs and technologies here on Earth.

So, people seem to love space science (especially the idea of aliens coming to Earth), but they don’t seem to want to fully engage by spending money on furthering our understanding of the universe.

ASM: Would you want to go to Mars with the Mars One mission?

ASM: Would you want to go to Mars with the Mars One mission?

MM: This may sound odd, but if I were to go, I’d rather go on a mission that’s run by NASA instead of a private mission. I think private industry has some role to play in space exploration (probably mostly mining asteroids for profit), but as a scientist, I believe in the methodical approach to sending humans to another planet, and I think a long-term plan operated by NASA has the best chance for success. NASA may depend on the vagaries of presidential elections and Congressional funding, but even that’s far longer-term than quarterly reports. Also, my wife wouldn’t let me go.

ASM: From whatever inside perspective you may have – what is the current state of NASA?

MM: Because NASA is so dependent on the election cycle, its missions’ futures are too uncertain. I don’t know what the answer is, but it would be nice for all of the scientists, engineers, staff, and private contractors who depend on NASA to be able to depend on funding lasting longer than a couple of years.

ASM: Do you think that sf movies/tv get the “science” right?

MM: Not usually, but that’s not really the point of those movies, is it? I used to get upset with movies or TV when the science was wrong, but then I realized that they also get every other profession and industry incorrect. I think it’s because movies and TV exist to entertain us, and real activities like doing science, arguing a court case, making a medical diagnosis, or other every-day professions aren’t really that entertaining looking in from the outside. Most of my day as a scientist is spent sitting at a computer trying to make sense of some bug in my analysis software. That said, I think shows like Cosmos and to some extent Myth Busters exist to illuminate science for the general public; science can be made entertaining, but I don’t think we can fault a producer for putting entertainment before accuracy.

ASM: What author influenced you the most? What works are your favorite?

MM: I really like Sagan, Le Guin, Susanna Clarke, Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Atwood, McCaffrey, Norton, and I could go on and on. Joss Whedon is someone who I think does a brilliant job of exploring the human condition while telling excellent and entertaining science fiction stories. My absolute favorite science fiction author is Iain M. Banks. I think his Culture novels have a wonderfully complex mix of technology, philosophy, psychology, and science fiction rolled into stories about the human condition.

Recent Comments