Jonathan Oliver is one of the UK’s top genre editors. He is also a novelist, short story author and creator of shared-worlds. Recently I interviewed him by email.

*

ASM: Welcome to Amazing Stories. You are editor-in-chief of three imprints – Solaris, Ravenstone and Abaddon Books – all published by Rebellion Publishing Ltd. What is your background and how did you end up in your current position? Perhaps for readers who are not familiar with Rebellion you could outline the idea behind each of your imprints?

Jonathan Oliver: My background is in academic publishing. I worked for Taylor & Francis for almost 7 years editing economics journals before I moved into genre publishing. I’ve always been a fan, however. Originally I was brought in to help launch and oversee the Abaddon range, which are shared-world action-adventure science fiction, fantasy and horror novels. I was also asked to oversee the 2000 AD range of graphic novels, which was a real delight.

In 2009 Games Workshop put Solaris up for sale and Rebellion brought it and appointed me the editor-in-chief. Solaris runs on a much more traditional publishing model, producing author-owned works of genre. Then last year we launched our imprint for children and young adults, Ravenstone.There we’re looking for remarkable books for young readers that don’t necessarily fit into a handy niche.

So, yes, lots to oversee. Which is why I asked David Moore, my co-editor on all the lines, to take over as commissioning editor on Abaddon books last year. And a fantastic job he’s doing too, bringing a new eye to the range and launching some exciting new series.

Another thing folk may not know about me is that I actually have a Masters degree in Science Fiction from Reading University. So I actually have an official piece of paper stating that I’m a Master of Science-Fiction. So it must be true!

ASM: So as an official Master of Science-Fiction what is some of your favourite SF, and indeed, Fantasy and Horror?

Jonathan Oliver: It’s so hard to pick favourites. And, also, saying something is your favourite sort of puts a cap on things – it’s like saying, the genre doesn’t get better than this. Whereas I want to go on discovering new favourites throughout my career and beyond. That said, the books that had the biggest impact on me as a child were Alice in Wonderland and Alice Through The Looking Glass. They really cracked open the imagination of a young boy and gave me a taste for the weird. Ramsey Campbell was a huge influence on my own writing and introduced me to the wider field of horror, as well as pointing to some of the best in literature outside of the genre.

Recently I’ve been hugely enjoying discovering Alan Garner, revisiting Robert Holdstock, and it goes without saying that I’m massively proud of the range of titles we’ve published, and working on a personal basis with some of my very favourite writers is a real blessing and a privilege.

Recently I’ve been hugely enjoying discovering Alan Garner, revisiting Robert Holdstock, and it goes without saying that I’m massively proud of the range of titles we’ve published, and working on a personal basis with some of my very favourite writers is a real blessing and a privilege.

ASM: Have your tastes changed over the years, and as a result of studying the genre in a formal, academic way?

Jonathan Oliver: My tastes have certainly evolved over the years and I’d be a pretty rubbish editor if they hadn’t. I think it’s important to keep on top of new developments in the field and we owe it to ourselves and our readers to help the field evolve and diversify.

As for whether the academia influenced my tastes… I think it influenced my way of thinking about texts more. I remember Edward James, my tutor on the MA, saying ‘I hope the course doesn’t put you off SF,’ but far from that it showed me that the genre was wider than I had ever suspected and there was a lifetime of texts to study as the genre continued to change and expand.

ASM:How important do you think it is to read outside the genre, to have a wider picture of what is going on in the literary world?

Jonathan Oliver: I think that if you have a broad overview of literature, you’ll have more of a sense of what does and doesn’t work in your genre of choice. Cross pollination between genres and styles keeps them fresh and alive. Writers do not evolve by living in ghettos, and you’re really only going to find your voice after you’ve listened to many others.

ASM: So what are some recent or forthcoming Solaris titles you’d like to talk about? What new titles should readers be looking out for, and why?

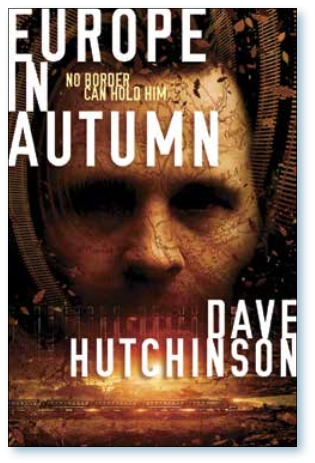

Jonathan Oliver: As for our own titles, I really don’t like to pick favourites as I think we have a stunning line-up overall. However, there are a few debuts I’m really excited about. We’ve just released the debut novel of Dave Hutchinson, a near-future spy thriller called Europe in Autumn. It’s a brilliant Kafka-esque nightmare of politics and bureaucracies.

Jonathan Oliver: As for our own titles, I really don’t like to pick favourites as I think we have a stunning line-up overall. However, there are a few debuts I’m really excited about. We’ve just released the debut novel of Dave Hutchinson, a near-future spy thriller called Europe in Autumn. It’s a brilliant Kafka-esque nightmare of politics and bureaucracies.

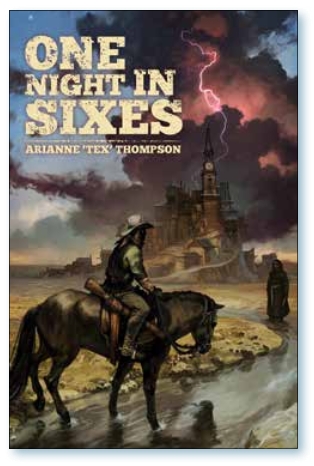

Also, this Summer we have the debut of one of the most extraordinary fantasy novels I’ve read in a long time, One Night in Sixes by Arianne ‘Tex’ Thompson. This is a fantasy Western novel of incredible depth and richness. Arianne’s ability to describe a setting and give you a sense that this place has history reminded me of Erikson’s Malazan novels. However, this novel is uniquely Arianne’s. To discover such a brilliant new writer and be able to bring a new voice into the field is always a thrill.

Folk hoping to check out the full range of our titles could do no better than heading to solarisbooks.com, abaddonbooks.com or ravenstone.com

ASM: I’m wondering, when it comes to taking on a new writer, or even an established author with a new novel or series, how much of your decision is based on your own personal enthusiasm for the book or series and how much is based on how commercially successful you think it might be? How as an editor do you judge a book’s chance of success? And are you sometimes able to take a risk on something that doesn’t seem particularly commercial but which you just think is exceptional and might surprise everyone?

Jonathan Oliver: Obviously, when you commission a book you want it to succeed and there are a certain amount of things you can do to make sure a title has a good chance – secure broad review coverage, advertise in the genre press, utilise social media etc etc. At the end of the day, however, there isn’t a formula for why one book becomes a bestseller and why another will only shift a few copies. You cannot predict a bestseller. You can certainly play a trend, but the thing about trends is that they can end overnight. Generally we look to commission a title a year or more in advance of its release, and as much as it would be useful to do so, one cannot see a year into the future.

Jonathan Oliver: Obviously, when you commission a book you want it to succeed and there are a certain amount of things you can do to make sure a title has a good chance – secure broad review coverage, advertise in the genre press, utilise social media etc etc. At the end of the day, however, there isn’t a formula for why one book becomes a bestseller and why another will only shift a few copies. You cannot predict a bestseller. You can certainly play a trend, but the thing about trends is that they can end overnight. Generally we look to commission a title a year or more in advance of its release, and as much as it would be useful to do so, one cannot see a year into the future.

So, my main criteria for commissioning a book is whether or not it’s excellent. I think I’m a pretty good arbiter of taste (I bloody well hope so, at least, as that’s sort of my job), so the chances are that if I love something then there will be a goodly amount of readers who will also love it.

The good thing about being an independent press is that we are in a position to take risks, we can try out new things without first having to appeal to the gods of a marketing or sales department. And we can also act very quickly if we see a book that has outstanding potential; hence we snapped up the paperback rights to Lavie Tidhar’s Osama, shortly after it was released in a limited run from a specialist press.

ASM: A lot of readers probably first came to know Lavie Tidhar’s writing through his short stories, which traditionally were considered the heart of the genre. You edited the anthologies The End of the Line and House of Fear, both of which I enjoyed a lot. And apart from the anthologies which you edit yourself, Solaris publishes the Ian Whates’ edited Solaris Rising series, and forthcoming is Jonathan Strahan’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year series, starting with volume 8.

Yet the perceived wisdom is that story collections don’t sell anywhere near as well as novels. Is this true in your experience, and how does Solaris being an independent press affect your ability to publish original anthologies? When you have a great idea for an anthology can you just go with it?

Yet the perceived wisdom is that story collections don’t sell anywhere near as well as novels. Is this true in your experience, and how does Solaris being an independent press affect your ability to publish original anthologies? When you have a great idea for an anthology can you just go with it?

Jonathan Oliver: One of the advantages of publishing a roster of annual anthologies is that it broadens the field fairly quickly. We’re consistently presenting new writers and championing diversity in the genre with our anthologies. As for whether they’re a hard sell? Well, the digital revolution in publishing has been a boon there – anthologies do very well in e-book, especially the science-fiction anthologies, and our paper sales are encouraging and our continuing to build. In fact, I’m delighted that we’re one of the biggest publishers of short stories in paperback in the US and the UK. I’ve always loved short stories and I believe that they are the very lifeblood of genre.

My own anthologies are very theme-focused. I think that this helps to inspire the contributors as well as presenting a diverse range of tales on genre tropes. I think that it’s useful for horror anthologies to have a focus.

ASM: A few years ago there was the idea that ebooks would completely replace traditional paper books, but now reports seem to suggest that the ebook market has grown about as big as it is likely to, and that publishing is starting to reach a ‘new normal’ with a healthy balance between sales of paper and ebooks. Do you think traditional and ebooks will coexist long term?

Jonathan Oliver: E-books are an important and developing part of the publishing industry. There are some arguments that say sales have plateaud of late, though I’ve also seen data that shows sales steadily rising. At present, paper still makes up the majority of our sales, but the digital revolution doesn’t leave me in a state of breathless fear, rather I think it presents us with new opportunities and the chance to greatly expand our audience. Publishing, unlike the music industry, did not bury its head in the sand when it saw the oncoming digital revolution. I think traditional books are still going to be around for a good, long while.

ASM: You’ve written two novels set in the shared-world fantasy series Twilight of Kerberos: The Call of Kerberos and The Wrath of Kerberos, which are published by Abaddon. Nearly all shared-world novels are spun off from a franchise, usually film or TV, or perhaps a game. But Abaddon shared-worlds are different. You’ve described them before as ‘franchise fiction without a franchise.’

ASM: You’ve written two novels set in the shared-world fantasy series Twilight of Kerberos: The Call of Kerberos and The Wrath of Kerberos, which are published by Abaddon. Nearly all shared-world novels are spun off from a franchise, usually film or TV, or perhaps a game. But Abaddon shared-worlds are different. You’ve described them before as ‘franchise fiction without a franchise.’

How do you set about creating a shared-world – perhaps you could introduce the Kerberos for those of us who’ve not read the books yet?

Jonathan Oliver: Shared worlds are usually, initially created by us, the Abaddon team. So that’s me and David Moore, though lately David is in the driving seat of Abaddon. We come up with the sort of story we want to tell, the sort of story that will make a fun series, and then we go about selecting an author to at least bring the first novel to life, though usually they go on to do more books in the series.

The world of Kerberos was a part of my desire to see fun, adventure-lead fiction back on the shelves. I mean, I love an epic fantasy as much as the next fan, but I grew up with 200 page, or less, fun fantasy stories – by writers such as Fritz Leiber, Robert Howard, Karl Edward Wagner and the like. So, I wanted to bring that back a little while mixing it with the horror sensibilities of Clark Ashton Smith and H.P. Lovecraft. It’s pulp fantasy with a heavy dose of Weird Tales, more so in the two books I wrote as I’m the horror nut.

Writing the two novels took a long time (as I had to do it all in my spare time) but was great fun and I owe a huge debt to my editor on both books, Rebecca Levene, in helping me become a better writer.

ASM: Will you be writing more novels in the future, either shared-world, or stand alone titles? I know you write short stories as well. Where can we find some of your stories, and do you have any new ones coming out soon?

Jonathan Oliver: I’m tinkering with something at the moment, novel-wise, but finding time to write is a little tricky. So short stories are usually a little easier for me, though I never find writing easy per se.

Jonathan Oliver: I’m tinkering with something at the moment, novel-wise, but finding time to write is a little tricky. So short stories are usually a little easier for me, though I never find writing easy per se.

Anyway, as for where you can find some of my short stories: I’ve been in a couple of Jurassic London’s Pandemonium anthologies, ‘The Day or the Hour’ appeared in Pandemonium: Stories of the Apocalypse and ‘Raise The Beam High’ appeared in A Town Called Pandemonium. The follow up to that story, ‘Reel People’, is due to appear in The Streets of Pandemonium this year. I have a story forthcoming in Ian Whates’ La Femme called ‘High Church’ and my SF story, ‘Baby 17’, will appear in the next BFS Journal.

White Horse, one of my favourite and most personal stories, appeared in The Alchemy Book of Urban Mythic last year, and my love letter to the horror genre, ‘The Horror Writer’, appeared in Terror Tales of London.

I’ve just finished a story called Peter and The Invisible Shark, that has gone off to the editor. And now I’m trying to prod the corpse of the novel to see if I can get it to breathe again.

ASM: I know that you are a Christian, which is something relatively rare in the world of SF, fantasy and horror. How does your faith affect your approach to these genres?

Horror, in particular, a lot of Christians seem to have a problem with. As a Christian what is it that attracts you to work in these genres, and what does your faith enable you to bring to them?

Jonathan Oliver: I’m not sure how relatively rare it is to be honest. I mean, I know of people of many faiths in the genre community, as well as none. As for how my faith effects my approach to working in the genre, I’d say pretty much not at all. I mean, my faith pervades every aspect of my life, but it’s not something I push on other people. I approach a story pretty much like any other editor would and try and help the author make it the best story they can tell.

And I’m going to take you to task, a little, with your generalisation. I’m really not convinced that the Christian community has a problem with horror at all. In fact, some of the early practitioners have been people of faith – MR James, Arthur Machen etc. As for whether there’s any perceived spiritual threat in exploring the darker aspects of life through fiction? Well, that’s just nonsense, as what we are dealing with is FICTION.

You’ve reminded me of a question I was asked when I was one on a comics panel at the Greenbelt Festival (an ecumenical festival of faith and culture). One man asked me whether I thought it was okay to enjoy the Preacher comic books as a Christian. Of course it is. I don’t know anything about Garth Ennis’s beliefs, but Preacher is a story. Garth wrote about a fictional God. The God in Preacher is not the one I recognise, but nor does the idea of exploring any aspect of God through fictional means offend me.

I find it very difficult to be offended on a religious basis by stories to be honest. I was always surprised when some referred to The Exorcist as an ‘evil’ film, as it is by far one of the most conservative horror movies I’ve ever seen. It reaffirms the traditional views of heaven and hell, angels and demons and demonstrates that only faith can protect you from spiritual evil. If you want to see a morally corrupt film, try Kick Ass.

I find it very difficult to be offended on a religious basis by stories to be honest. I was always surprised when some referred to The Exorcist as an ‘evil’ film, as it is by far one of the most conservative horror movies I’ve ever seen. It reaffirms the traditional views of heaven and hell, angels and demons and demonstrates that only faith can protect you from spiritual evil. If you want to see a morally corrupt film, try Kick Ass.

Sure, there are fundamentalists who bang on about Harry Potter being evil, about roleplaying games being evil, but these people are nutjobs. Harry Potter does not promote the use of witchcraft and you cannot cast real spells when you’re playing Dungeons & Dragons. Fundamentalists seem to think that the Bible is the end of the debate when it comes to the nature of God, when really it is very much at the beginning, and part of a continuing dialogue.

I don’t really think that my faith has had a huge amount of influence on my reading habits, though I am always interested in works that have themes concerning faith, and the nature of faith – and the complexities of belief find their way into my own fiction fairly frequently.

ASM: I wasn’t really generalising – I know a lot of Christians who are very uncomfortable with the idea of reading horror fiction, and others who simply dismiss it out of hand as disgusting and of no value. I’ve met a lot of others who have no problem with it at all. One Christian friend, very enthusiastically, has just discovered the work of Stephen King, and I know at least two ministers / pastors, one being my own, with complete sets of the Harry Potter books on their shelves. William Peter Blatty wrote The Exorcist as a reminder to an increasingly secular world, of the reality, as he saw it from a Catholic point of view, of the reality of supernatural evil.

But turning things around, have you ever found puzzlement or hostility from the genre community not perhaps to yourself personally, but towards your faith – assumptions perhaps about what you’re perceived to be about, rather than what you actually believe?

Jonathan Oliver: Fair enough. I’ve not really come across such views for a while, though. I grew up in the church (my Dad is a retired Anglican Priest), so I’ve come across some unusual opinions over the years. I remember in the late 80s the fuss in some corners of the church about roleplaying games. My Dad dismissed it as nonsense and continued to buy me Fighting Fantasy books. I suppose, yes, some people of faith would shy away from the darker subject matter, but there’s nothing wrong with exploring such themes. To know the light you have to also know the darkness. Yes, Blatty is a very traditional committed catholic. To be honest, I never really connected with The Exorcist. I actually found it a bit dull.

I never have experienced puzzlement or hostility towards me because of my faith. A lot of my friends are atheists and we get along just fine. I did once have someone describe themselves to me as a profound atheist, as though they wanted to challenge me a little, see if they could get a rise, but I’m happy to talk to anyone, and atheism can open up much interesting debate. Generally I find I have much more in common with humanism and the humanist movement than I do with tub-thumbing Dawkin-ites.

I do sometimes see on social media the assumption that Christians believe in some sort of ‘bearded magic man in the sky’ (which seems a very reductionist view of faith), and that Christians don’t believe in evolution (which is nonsense. Most Christians I know do and have no problem reconciling faith and science) but none of these are personal attacks, rather they are silly things folk say on the internet. I do believe that most see personal attacks on people because of their faith as completely out of order.

*

You may also be interested in my review of the Solaris title The Fictional Man by Al Ewing

…is a freelance editor, writing consultant and story structure expert. To find out more, including hiring me to work on your writing project, read my profile or visit my website, To The Last Word.