- File Size: 953 KB

- Print Length: 576 pages

- Publisher: Orb Books; First Edition edition (August 16, 2011)

- $8.89 (Kindle)

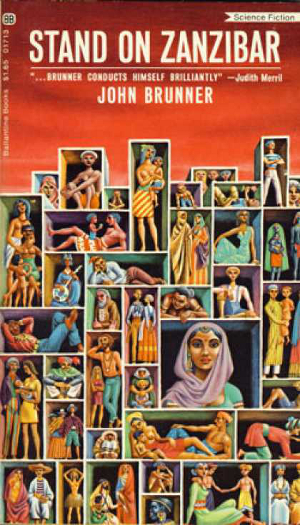

Stand on Zanzibar, John Brunner‘s 1969 Hugo Winner for Best Novel, was one of those books I always meant to get around to reading, especially when I came across an essay that suggested it was a precursor to cyberpunk. That argument can certainly be made, but it turned out to be much more.

I’m not going to attempt to analyze this sprawling 650 page novel. Instead a few observations:

* It’s set in the early 21st century. It’s amazing how, in so many ways, it remains an incredibly timely novel even though it came out in 1969.

* As with most SF writers of the era Brunner could not foresee what was coming with computers. A key “character” in the book is Shalmaneser, a super-computer bordering on AI. We get the sense that it is the only such one in the US although there may be a counterpart for Europe and another for China. (Yes, China is the big superpower rival rather than Russia.)

* His attitude towards women is paleolithic. Yes, there are some accomplished women in the book but they are minor characters. Most of the time they are “shiggies” (one of many coinages in the book; it should come with a glossary). Shiggies are young women who don’t have their own homes but live serially with various men for a night or for longer periods. Norman and Donald, the book’s protagonists, share a bachelor apartment and have engaged in “shiggie swapping.” There’s a feminist Ph.D. thesis waiting to be written about the novel. Or perhaps it’s already been done.

* There’s no question that he has created a rich, complex world: New York under a dome. Drugs legalized but taxed heavily if they’re from out of state. The job of “synthesist” which consists of simply learning as much as possible about anything and everything and then making connections that elude specialists. Strict controls on who gets to reproduce. Violence not only from terrorists and criminals but from “muckers” — people who have snapped from the overcrowded living conditions and who run amok.

Due to its structure of hopping from story to story to news feeds to random notes to all sorts of miscellany I found it something less than a “page turner.” In fact I had to give up one book on reserve at the library because there was no way I could finish Stand on Zanzibar before the hold ran out.

However, I’m glad I read it. Just as I urge young film students to see the classics and not just the latest releases, those of us serious about science fiction should also seek out the classics in the field that we may have missed along the way.

Recent Comments