It was my brother D who first introduced me to Iain M. Banks. The setting: a grim two-room apartment in Tokyo above a liquor store. The book: Use Of Weapons. Me: hooked for life.

It was my brother D who first introduced me to Iain M. Banks. The setting: a grim two-room apartment in Tokyo above a liquor store. The book: Use Of Weapons. Me: hooked for life.

I know of two great masters of the shocking twist. One is thriller writer Jeffrey Deaver. The other is the Scot who gave us the Culture novels, as well as a dozen equally good mainstream novels and a couple of stand-alone SF works

And now this shocking twist: He’s dead! Gall bladder cancer crept up and grabbed him at the age of 59, and if I knew where gall bladder cancer lived I would follow it home and rob its house and piss on its living-room carpet for good measure.

Banks left us 27 novels and one non-fiction book about whiskey. The fiction:

- The Wasp Factory [1984] | UK

- Walking on Glass [1985] | UK

- The Bridge [1986] | UK

- Consider Phlebas [1987] | UK | US

- Espedair Street [1987] | UK

- The Player of Games [1988] UK | US

- Canal Dreams [1989] | UK

- Use of Weapons [1990] | UK | US

- The State of the Art [1991] | UK

- The Crow Road [1992] | UK

- Against a Dark Background [1993] | UK | US

- Complicity [1993] | UK

- Feersum Endjinn [1994] | UK

- Whit [1995] | UK

- Excession [1996] | UK

- A Song of Stone [1997] | UK

- Inversions [1998] | UK

- The Business [1999] | UK

- Look to Windward | UK

- Dead Air [2002] | UK

- The Algebraist [2004] | UK

- The Steep Approach to Garbadale [2007] | UK

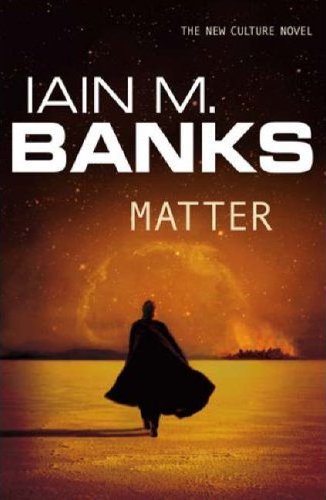

- Matter [2008] | UK | US

- Transition [2009] | UK | US

- Surface Detail [2010] | UK | US

- Stonemouth [2012] | UK | US

- The Hydrogen Sonata [2012] | UK | US

I got this list from Banks’s website, which had not, as of this writing, been updated to reflect the news of his death. Don’t look at it if you’re feeling fragile.

I got this list from Banks’s website, which had not, as of this writing, been updated to reflect the news of his death. Don’t look at it if you’re feeling fragile.

I have read the lot except for Feersum Endjinn, which I just could not get through. God knows I tried. Many of Banks’s other books I have read several times. To this day, Use of Weapons is my favorite, but Consider Phlebas and Against A Dark Background run it close. The Business is also a reread–it is that rare thing in Banks’s oeuvre: sweet. As he grew older he seemed to like humanity less. The second Gulf War radicalized him politically, with results that make Dead Air less than the stonking success it should have been–it’s got a few too many anti-Dubya rants in it; but his sense of outrage was fresh at the time he wrote that, and his politics never interfered with his fiction again afterwards. He was simply too good a writer for that.

Banks was an outspoken atheist and it’s arguable that this shapes his whole oeuvre, especially the Culture novels. The universe of the Culture is one where religion is quite definitely relegated to its place as a self-deception for stupid people. But fiction reveals its true nature less reliably in what it says about itself than in what it is. What then is Banks’s work? It is joyous. It dances. It leaps, cartwheels, somersaults, and does gravity-defying grand jetés of sheer exhilaration–never bored, never faltering, finding the humor in every situation, reveling in the greatness, rareness, muchness / Fewness of this precious only / Endless world. Especially in his early work, Banks caught the spirit of the Song of Songs.

The theme of moral responsibility runs through Banks’s whole body of work. From Horza in Consider Phlebas–maybe my favorite Banks protagonist–to Djan Seriy Anaplian in Matter, his characters follow their consciences, sometimes despite themselves and always in spite of the forces ranged against them. Their stories often culminate in deeds of hardcore nobility. (Remember Anaplian’s climactic scene? Wow!) Even the Chairmaker struggles for and arguably achieves redemption, guided by an extraordinary moral conscience–extraordinary, that is, in the context of a universally leisured humanity kept as pets / companions / study subjects by near-godly Minds. Banks tries to handwave this by harping on the moral fastidiousness of the Minds themselves, which is meant to somehow osmose to the humans of the Culture,even in the absence of formal religion or any sort of ritual taken at all seriously–but it doesn’t wash. The morality of the Culture is not the way people really would be if they lived in an age of post-scarcity frivolity. It is Banks’s own granite-spined Scots morality, and it gives his work an essentially conservative character, under all the techspeak and razzamatazz.

I’m mostly talking about the Culture novels here. But you can see the same morality in most of his mainstream novels, too, slightly blurred by the greater familiarity of the settings. The exceptions to this rule, such as A Song of Stone and maybe Complicity–books in which there just aren’t any good guys–prove it: they are his least successful.

I’m mostly talking about the Culture novels here. But you can see the same morality in most of his mainstream novels, too, slightly blurred by the greater familiarity of the settings. The exceptions to this rule, such as A Song of Stone and maybe Complicity–books in which there just aren’t any good guys–prove it: they are his least successful.

Still, an unsuccessful novel by Iain Banks, with or without the M, still clears with ease any hurdle that the rest of us might like to set for ourselves. Above and beyond the hours and hours of enjoyment his books have given me, Iain Banks was my teacher. He taught me something more vital than any narrative trick. He taught me how speculative fiction must rejoice. (And it’s just as well that the rejoicing is in the journey, not the destination, because, er, I’m not getting there any time soon.)

Banks’s last book, a mainstream novel entitled The Quarry, is coming out on June 20th. But I’m not going to read it. At least, not for a while. It’s about a man dying of cancer. This is one shocking twist too many!

Requiescat in pace seems like the wrong epitaph for a man whose work was so full of joy. Here’s a better one:

Listen! My beloved!

Look! Here he comes,

leaping across the mountains,

bounding over the hills.

My beloved is like a gazelle or a young stag.

Look! There he stands behind our wall,

gazing through the windows,

peering through the lattice …

Leaping over the mountains, bounding over the hills–that’s what I think Iain Banks is doing now, wherever he is. Free at last.

***

Recent Comments