Intelligent robots have been part of the SciFi lexicon since before Fritz Lang’s seminal file Metropolis. While it’s fun to imagine what the world would be like with intelligent machines, the sad truth is that “strong” Artificial Intelligence (AI) will probably never happen.

Intelligent robots have been part of the SciFi lexicon since before Fritz Lang’s seminal file Metropolis. While it’s fun to imagine what the world would be like with intelligent machines, the sad truth is that “strong” Artificial Intelligence (AI) will probably never happen.

I recently read an interview in The New York Time Magazine recently interviewed Ray Kurzweil, who’s made a 40-year career out of predicting that strong AI (i.e. a machine that can pass the Turing Test) is just around the corner.

Unfortunately for Kurzweil, while digital computers are exponentially faster than they were in the 1970s, they’re marginally more intelligent (if at all, depending upon how you define the term) they were 40 years ago.

Apple’s Siri, for example, is only marginally better at deciphering human speech than programs that were running decades ago, and no program–even those running on multiple supercomputers–have the ability correctly interpret idioms or put successive sentences into context.

What passes for AI today is the result of incremental (and relatively minor) changes to pattern recognition algorithms and rule-based programming concept that have been around for many years. While there are plenty of programs that use these algorithms, “strong” AI (in the sense of a computer than can think like a human being) is junk science.

While digital computers can do brute force calculation that allow them, for instance, to win at chess, the domains in which such programs operate are perfectly defined and therefore utterly unlike the real world.

That hasn’t stopped Kurzweil and his ilk from making predictions, year after year, decade after decade, promising that AI is just over the horizon (“within 20 years” is the typical mantra).

Meanwhile, there have been no breakthroughs in AI and no potential breakthroughs in sight. This situation is unlikely to change. In fact, AI (in the sense of actually passing a Turing Test) may simply not be possible using digital computers.

The Times interview mentioned Kurzweil’s most recent prediction that “by 2045, computing will be somewhere in the neighborhood of one billion times as powerful as all the human brains on earth.”

The implication, of course, is that computers will be “smarter” than humans, if not now, then certainly by that date. However, that argument hinges the assumption that digital computers and human brains are similar.

They’re not. Not even slightly. In fact, a single human brain is more complicated than all the computers in the world today. Let me explain.

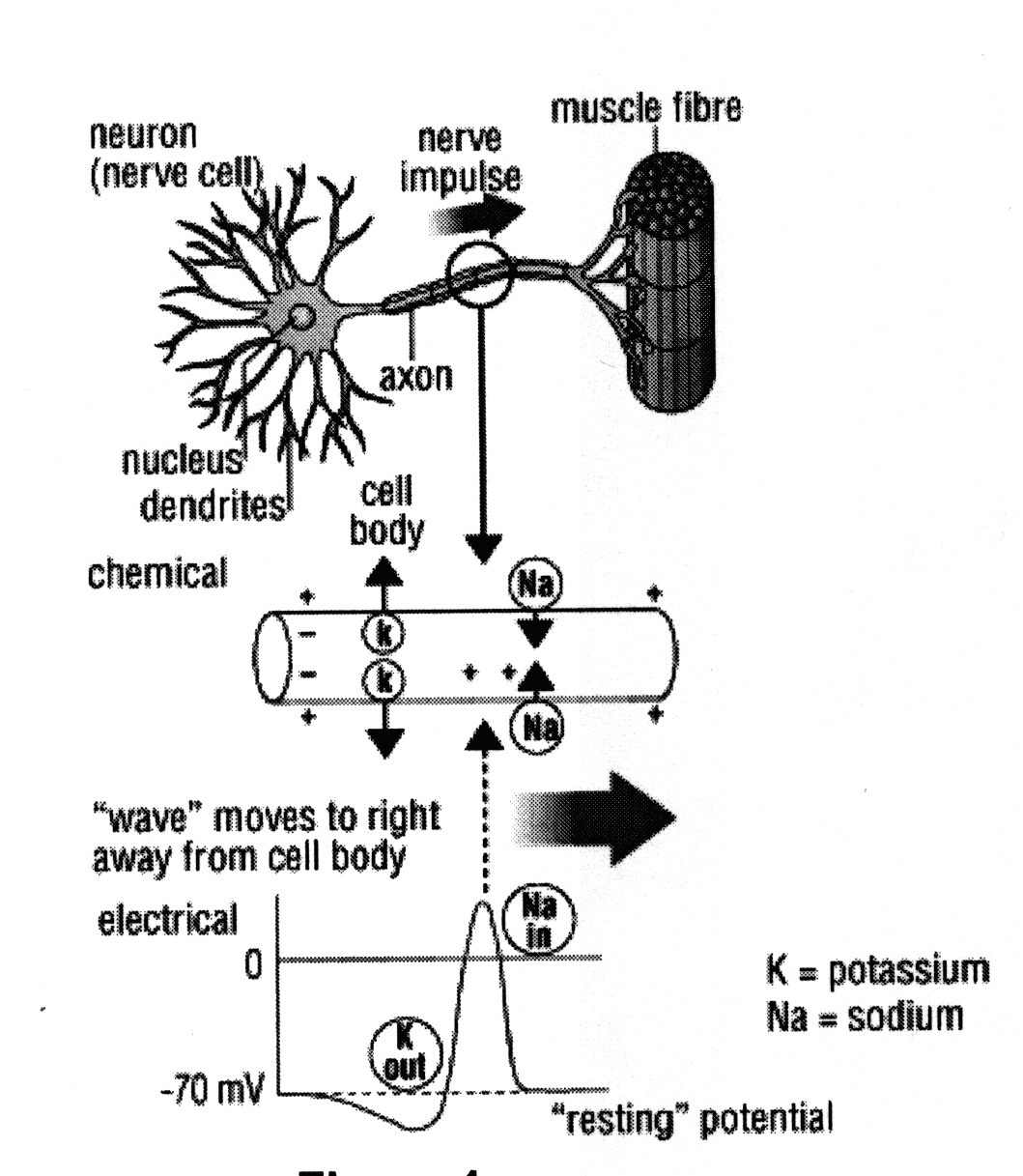

The human brain consists of about 100 billion neurons. If each neuron were a “bit” (as in a computer memory) that would represent less than a gigabyte of memory. But neurons aren’t “bits”; they’re massively complex potentiometers.

In the human brain, information travels from neuron to neuron (through axons) in the form of a wave. While the wave form has a valley and peak that are superficially similar to the Off/On state of a bit, wave forms can actually have “n” number of potential states.

Neurons, in other words, are exponentially more complex than bits, a fact that makes the human brain infinitely more complex than any digital computer.

For example, with three bits you can represent any value between 0 and 7 (i.e. 000, 001, 010, 011, 100, 101, 110, and 111.) With three potentiometers, by contrast, you can represent millions of values.

Think of it this way. Suppose each potentiometer can represent a fractional value between 0 and 1 (including 0 and 1) in, say, increments of 1/1000th. The number of discrete states that only three such potentiometers can represent is therefore 1 billion (i.e. 1,000 * 1,000 * 1,000). The complexity increases exponentially with the number of potentiometers.

In other words, the 100 billion neurons in a single human brain are inconceivably more complex than 100 billion bits, or even a billion * billion * billion bits. Because of this, it’s highly improbable (and probably impossible) that the human brain can be effectively modeled on a digital computer.

It's possible to critique the projections of Kurzweil and his "ilk" (an unfortunately offensive term) without letting the irritation color the critique too much. It's an awkward place to be, between a serious professional critique and a rant, and I think this piece is better off as the former without succumbing to the desire for the latter. However, "never" is a ridiculous claim for something that is basically an engineering problem, albeit a very complicated one, and one for which we have a working template to solve. (Agreeing with the final points from Michael Webb, above.) It's sufficient to simply say that the current claims for strong AI on the timescale of years or decades are based on faultly assumptions, and different approaches will be needed for this staple of science fiction to ever come to fruition.

It's a blog, not a scholarly article. A bit of ranting comes with the territory.

I found this to be a pretty weak article. "AI will probably never happen" ? The arguments given are thin and unconvincing.

To correct one factual error : Kurzweil has not made a career out of predicting that strong AI has been "just around the corner". He's been remarkably consistent in his predictions: hardware with the raw power of a human brain by 2010 (correct, under our current assumptions of how brains work) and general intelligence by 2030 (we'll see, but I believe it'll be sooner).

As to the argument that the brain is "too complex" to be modelled by a computer – that's just hand-waving mumbo jumbo. All experiments to date have supported the view that neuronal firings are essentially digital in nature : it's not the precise shape of the spike that matters, but the timing. We've already got good models of specific brain areas that work well under these assumptions, and we're quickly reverse-engineering others. They all seem to operate with the same basic principles.

Even if it is true that a brain really is a billion times more complex than we believe, then that effectively adds 30 years to the arrival date, assuming a doubling every year. Perhaps you might say 100 is a more conservative number, but regardless that's a lot different from "never".

Think about innovations that have occurred in the last 5 years, such as rapidly-improving 3d vision, self-driving cars, simultaneous translators… it's flat-out wrong to say that the field of AI isn't progressing. On the contrary, it's moving faster than ever before.

What's more, tools such as optogenetics and micro-slice imaging are letting us investigate brain circuits with astonishing precision. Take a look at "sciencedaily" or similar news sites, and you'll see a continuous stream of announcements about new discoveries. The trend is unstoppable. Within our lifetimes, I believe it's inevitable that even "human" qualities such as creativity, empathy and moral behaviour will have been reverse-engineered and replicated in silicon.

But I guess we won't know for sure until it happens….

Well, we've been waiting for "Strong AI" ever since Turing predicted it would happen sometime in the 20th century. However, I'm not going to argue with somebody who believes that the outcome of a particular branch of research is "inevitable." But, then there's more than a little bit of faith-based thinking in area of strong AI. Witness Kurzweil's tin-foil-hat notion that human beings will become immortal by implanting their brains in computers.

Yeah, that's gonna happen.

It's a huge leap of faith from today's AI technology — which can't even solve a simple captcha or decipher a name spoken with an accent — to machine that can emulate human thought. Today's systems are marginally (at best) better at pattern recognition than the systems of 30 years ago. Since I started following AI in the 1970s, I've seen the predictions come and go… and the reality stay pretty much the sames, despite the progression of Moore's law.

But, go ahead and be a true believer if it makes you happy.

Fair comment Geoff, "inevitable" is a very strong claim ! Sorry if it sounded arrogant, that wasn't my intent. It just seems to me that, for the first time in history, we're within reach of a solution : we have the necessary technology (in terms of imaging tools and computer power), and now it's "just" a matter of applying it. Perhaps it turns out that brains really are doing something that's far beyond our current understanding… in which case I am dead wrong. But yes, I guess I have faith that this isn't the case ! Here's hoping …

I'm actually aware of the comparisons between a human brain and a computer. Most people don't understand that the human brain is in fact a lot more complicated than a modern computer, as impressive as modern computers may be.

Frankly though, the comparisons that you are drawing beyond that are not particularly apt. Complexity or computational power isn't really the issue. The issue, simply put, is creativity. Computers can do certain kinds of logical processes far better than a man, but what they cannot do is be creative. They are awful at deciding what activities are important for survival. And something else which has been incredibly difficult is designing a robot to simply walk on two legs.

To us, walking is simple, because we evolved to it, but getting a robot to walk across the room on two legs has actually proven rather difficult. The Japanese sort of pulled it off, but if you look closely you will notice that their robot's feet don't stray far from the floor at any given moment.

I frankly find it very silly though when people say how unlikely it is for these things to happen. Although 'sentient' robots are something that people like to read stories about, the truth is that we haven't really contributed nearly as much brainpower towards making a 'creative' intelligence as we have towards making bigger hard drives or faster processors. (And those technologies do not, by themselves, contribute to that sort of an intelligence any way.)

The truth is, most of us don't really want our robots to be creative. We don't want them to decide on the relative importance of the tasks we assign them, or when to do them. Or even if they should be done at all. The amount of time that people spend talking about the Turing Test, or the number of fiction stories don't really translate to the amount of time that scientists

spend really working on something like that.

And frankly, the idea that you can judge based on the things your describing whether it will ever happen is kind of silly. We have no idea what technologies we will develop in the future.

Every generation comes up with technologies that previous generations would have judged impossible. And every generation we need people to once again tell us what we can't do, and that's the role you are filling for us right now.

Oddly I just ran across an article about AI being naturally cooperative with human intelligence rather than competitive.

https://www.cnn.com/2013/02/03/opinion/sankar-huma…

Some of my motivation for my post was my ongoing irritation at Kurzweil, who handed me a line of provably ridiculous BS when I interviewed him about ten years ago.

Interesting! My entirely unscientific gut feeling about this has always been that the problem with computers is that they can only do "yes" and "no", they can't do "perhaps". Now you seem to be saying that the human brain can do not only "perhaps", it can do five different states of likelihood, so to speak (and to remain within the metaphor).