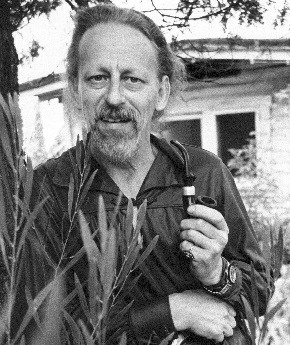

2013 Feb 10 – Theodore Sturgeon, aka/Edward Hamilton Waldo, is best remembered for asking “What’s the next question?” In some portraits, you’ll see Sturgeon wearing a “Q,” with an arrow pointing forward, suspended from a thin, silver chain around his neck. He believed in questioning our assumptions. He would push further inquiry by suggesting that you “ask the next question.” Our original sin, in a sense, was our failure to pursue further inquiry.

I suppose I could argue that Sturgeon was really the true father to our favorite Vulcan, Spock, since he coined both the phrase “live long and prosper” and the accompanying split-fingered hand gesture. Sturgeon’s story “Amok Time” aired on Star Trek in 1967 and immortalized the Vulcan mating ritual of “pon farr.” This teleplay, and the 1966 episode “Shore Leave,” put Sturgeon firmly in the Star Trek universe. Other Star Trek episodes he wrote, that were never produced, introduced the idea of The Prime Directive.

Humanity undoubtedly has a wide range of perspectives concerning human sexuality, but individuals commonly tolerate only a narrow vision of the same. Sturgeon was capable of discussing the foibles of human sexuality without offending the great masses. Not–I think you’ll agree–an easy task.

In The Sex Opposite, when humans murder aliens during an act of alien asexual reproduction, the bodies are taken to the morgue where a staff member is questioned by a news reporter. Both meet with one of the reclusive aliens who then engineers retribution upon the murderers. Although the alien is not directly involved, the murderers are themselves undone. Sturgeon somehow manages to bestow a greater sense of humanity upon these aliens than humans themselves possess.

One of the things that I admire about Sturgeon’s work is that it’s so often clean–or efficient, if you’ll allow. His character development is frequently quick off the mark, compelling you into the story. And his use of conflict between humans isn’t necessarily a set of black-and-white judgments. His characters wrestle with their perceptions, often remain good people, but struggle with moral conundrums. They are simply committed to different viewpoints.

Somewhere, in my dim past, I remember passages from text books on how much richer a writer’s writing can become when the story’s conflict is based on a struggle between one good character and another good character. Sturgeon does it gracefully; you might not even notice while you’re being carried along in his stream of consciousness.

Slow Sculpture is a short story; a quick read with high impact. It’s a clean, direct, compelling read. With only two characters, Sturgeon gets right into the elements of character, conflict, and curiosity. The protagonist cures his visitor of cancer, but reveals his own illness–a cancer of the spirit. His visitor is unable to just leave after her own recovery. Facing the unhappy soul from the opposite side of an ancient, but tortured and twisted bonsai, she manages to rescue the brilliant engineer from his own past and deep-seated guilt.

His novella, Baby Is Three, reinvented itself as the novel, More Than Human, which, in 1954, won the International Fantasy Award, and in 2004 was nominated for a retro Hugo award. This is another work that falls in those categories of re-readability and attracting a new generation of readers.

In The Microcosmic God, Sturgeon’s protagonist is obsessed with his own research and leaves humanity behind in his pursuit of knowledge. The scientist’s banker, who he disdains, is constantly pestering him for yet another profitable invention. He off-handedly passes his applications to his banker, then turns his back on the affairs of humankind. This proves problematic when the banker’s moral center drifts toward malfeasance and the scientist discovers what the banker is really up to…including murderous intent and megalomania.

I often find my mind wandering into social issues while reading such works. They may have been written in previous decades, but writers like Sturgeon were often tackling ticklish, ethical issues of their day. The progress of humanity continues and new writers are finding new targets for their concerns, but many of the themes remain similar and nearly identical.

What is the human condition? What makes a human … human? How do we define what is normal? Is human evolution to be irrevocably married to technological progress? Is there ever a time when we can embrace technology without reservations?

Sturgeon, I believe, would have said NO to that last question. In the final judgment, each citizen has to question what authority is demanding we believe. We can’t just assume that experts are always right. We have to question everything and like Sturgeon, we need to ask the next question. Asking the next question stops being a mere question, but a duty to humanity. A large part of that duty is to remain the watchdog of well-meaning scientists. To continue to ask the next question is not just asking: “Why did they create this evil?” Ask the next question and ponder: “How did a person, with good intentions, go so awfully awry?”

Good plot development should find it’s roots in reality. Reality is filled with scenarios of good versus good. Many well-meaning scientists don’t see the evil they are creating, but have become blinded by the potential of their work. The pursuit of trying to do medical research using stem cells, or the ongoing research on genetically modified foods, are just two examples of this kind of conflict; conflict that arises between researchers and public perceptions of unintended consequences involving two groups of equally well-meaning individuals.

Perhaps this is why I love science fiction. There are many axioms underlying SF and one of them is that a lead character, seeking resolution in the story, is striving for a better tomorrow. There’s an unspoken truism of optimism, even in the most bleak, dystopian plot. Tomorrow will grant us respite from today’s struggle.

Okay. Not always. And a few of you, I’m sure, were already questioning that axiom, about a better tomorrow. It should not be a blanket assurance to cover every SF story you’ve ever read so I suppose now would be a good time to paraphrase …

“Sturgeon’s Law: Ninety per cent of SF is crud; in fact, ninety per cent of everything is crud”

Sturgeon’s Law might be optimistic. In principle, I think he’s right. You filter through lots of gravel and sand, find plenty of pyrite, but little true gold.

Let me mention another law. I occassionally review Keith P. Graham’s website: 10 Laws of Good Science Fiction. His rule Number Four is No Nazis. You might think this law would be unnecessary, but it seems there’s always someone plugging away for the Nazis. With just a little research on Nazi occurences in stories, comics, and movies, you’ll quickly discover how ubiquitous Nazis truly are. There must be hundreds, if not thousands, of titles to review. There’s lots of mica flashing in this pan, but very little gold.

I not only find the use of Nazis a tired excuse for a villain, but I find their employment somewhat disturbing as it seems to trivialize the reality of Nazi horrors. With so many interesting subjects in science and culture to pick from, you’d think writers could stop glorifying these sociopaths and try a more original approach.

When next you read something cliche, achetypal, or improbable, let your suspicions guide you. Go Sturgeon and ask the next question. In fact, ask twenty if that’s what it takes. You might teach yourself something by pursuing some further inquiry.

Theodore Sturgeon belongs in the Big Four of the Golden Age of Science Fiction (Theodore Sturgeon, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, and A. E. van Vogt). I think there’s one thing that might grant him special recognition, at least from SF afficionados, and that’s his conceptualization of The Prime Directive.

I haven’t found an official Star Trek definition for The Prime Directive, but I’m not surprised. That could hamper story development and future flexibility. But for fans, it’s like finding cracks in your dilithium crystals. Sometimes working within constraints makes for a better story. Despite this, I suspect that Sturgeon’s contribution will outlive the contributions of the other Big Four.

Someday, in deep space, a terran spaceship will arrive at a planet populated by aliens and The Manual On First Contact will be broken out. The captain will click the manual open to the first chapter and she’ll read the heading, in a large, boldfaced font: The Prime Directive. She will proceed, with caution, to reread the whole chapter before deciding what she will do.

Those of you who aspire to better yourself should check out The Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award. While you’re at it, there are Theodore Sturgeon Ebooks available. Perhaps looking up some of his works will point you down the path to your own future and you”ll end up listed on the permanent award that lists all the winners of The Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award.

Um…interesting article. Especially that picture of Sturgeon with the purple background! We’re all having a laugh, since I actually know the guy you have pictured there. How in the world did you guys end up using that pic? They kinda look similar, but that’s NOT Sturgeon. HAHAHAHAHA

I am a big fan of Theodore Sturgeon, have a lot of signed books, limited editions, and rarities, so it really amused me when I was reading this article and came across a picture of a young Theodore Sturgeon that I instantly knew was not him…because it’s a picture of me. I’ve posted a lot of things about Sturgeon in weird places, and made a fairly accurate fan page for him on My Space back in the day, which is where I’m betting this pic came from. However, I do have a passing resemblance to him though.

Still made my day.

I appreciate your posting that information, especially for including the link. I admit, I was both unaware of the tandem presentation of Campbell and Sturgeon awards, but also that there were writing courses before and after the conference.

I'm planning on reviewing Harlan Ellison's work eventually. (How could I not?) He ending up writing some Trek episodes (Like – City on the Edge of Forever), but I need to really research him. It's always amazing to me how many places some of these SF luminaries crop up in. One reason I remember him is that in an interview he once said that he had never stooped to writing sequels. He wanted the challange of having to write new material every time he sat down in front of his typewriter.

Many thanks for the info, R.K.

The Campbell Conference occurs every year in June at the University of Kansas. The Campbell and Sturgeon awards are presented at the conference. There are also very productive writing classes that occur before and after the conference. All of these events are sponsored by the Center for the Study of Science Fiction. Check out the link below for more information.

https://www.sfcenter.ku.edu/campbell-conference.ht…

Thanks for the suggestion. Although getting away is problematic for me, I still like to know the where and when. If you think about it, add some details.

Actually, I'm in the process of reviewing works of his I haven't read before. It's a real kick to rediscover little read works by otherwise well-known authors.

Theodore Sturgeon is truly one of the giants in science fiction. (They named an award after him. nuff said) I confess I had no idea he had done Star Trek episodes. I did know Harlan Ellison had. I will have to review his episodes more closely.

If you get the chance, show up in Lawrence, KS for the presentation of the Sturgeon. You'll be glad you did.