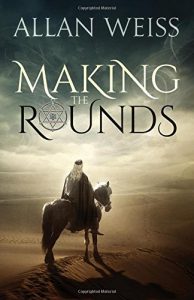

- Making the Rounds

- Allan Weiss

- Paperback: 200 pages

- Publisher: EDGE Science Fiction and Fantasy Publishing (March 18, 2016)

- Language: English

- Kindle Unlimited:$0.00

- Paperback: $19.95

Are there any new ideas in speculative fiction? Sometimes it seems like there aren’t. Science fiction is dominated by space adventures and spandex. High fantasy often feels like a footnote to Tolkien, while urban fantasy often stops at vampires, zombies and misplaced fairy folk.

A couple of years back, I was on a panel at a con on whether or not there were new ideas in science fiction specifically. I believe that my main point then is relevant to all forms of fantastic literature: there are over seven billion people in the world, all of whom have unique stories to tell. There are many, many unique histories, many, many unique mythologies, many, many sources that could be used to create something truly novel. Indeed, original works of speculative fiction are often published by small presses, a kind of good news/bad news situation: they certainly exist, but they rarely break into mainstream literary consciousness (or,indeed, make much of a dent in the spec fic world.)

(The reason you don’t see truly original ideas more often in mainstream SF publishing is that it is hugely market-driven. The big publishers know they can make a ton of money with work that makes incremental changes on existing formulas, and, if all else fails, you can’t lose with a Star Wars or Star Trek tie-in book); why would they risk resources on original work that doesn’t have a known audience? Of course, some of the blame for this situation rests with readers who don’t demand more from publishers – oy! Don’t get me started!)

One strategy for creating something new is to introduce into speculative fiction something from the past that you rarely find in the genre. Allan Weiss does this in his short story collection Making the Rounds, to highly entertaining effect. His idea is to create a series of fantasy stories around a Wandering Jew.

The Jew in question is a wizard named Eliezer ben-Avraham. As a young man, he pursued forbidden Kabbalistic lore; as a punishment for his hubris, he was condemned to wander the desert to help anybody in need as long as they were willing to supply him with room and board while he was helping them. This isn’t epic fantasy with amassed armies of various creatures battling for control of territories; it’s about a guy trying to help people. I was totally enchanted by the premise. Making the basic idea of short stories helping people. Who knew such a thing was possible?

The time in which the stories are set is never mentioned; given the lack of modern technology and the desert setting, it could be 200 years ago, or it could be 2,000 years ago. This ambiguity gives the stories in the collection a timeless feel, a sense that their relevance will not soon be dated.

To ensure that we know that this is fantasy, Eliezer ben-Avraham’s only companion on his adventures is his horse, Melech (Hebrew for King). Not only can the wizard speak psychically with his horse, but Melech is more attuned to misapplied (read: evil) magic; he often knows what is wrong in a situation and advises Eliezer ben-Avraham on what to do (a case could be made that he is the real star of the stories). Melech exhibits a cynical view of humanity which is rarely proven wrong.

When we first meet him, Eliezer ben-Avraham is an old man, crotchety and constantly complaining about his physical infirmities. I found this to be somewhat stereotypical, but his voice, larded (if you’ll forgive the term) with Jewish constructions and Yiddish words and phrases, was wonderfully fun to read. Eliezer ben-Avraham’s narration also adds an undercurrent of melancholy to the book, inasmuch as he agrees with his horse about the foolishness of human behaviour. (The physical complaints, which become repetitive as they appear in almost every story, represents a common problem with short story series: you have to introduce basic character and situation details into most of the stories since you can’t be sure readers will have come across any of the previously published ones, but this can make for repetition when they are collected.)

As befits setting and character, the stories in Making the Rounds are unique: a Priest asks Eliezer ben-Avraham to locate a word that has left his sacred text; an idiot mayor of a town asks the wizard to create a Golem for him to solve a problem that is better solved by other means (because just about every problem is better solved by other means); Eliezer ben-Avraham comes across a 10 foot tall Menorah in the middle of the desert and is asked to help create and light the large candles necessary to celebrate the eight days of Passover).

Making the Rounds is a book that all should be able to enjoy. On the one hand, Jews should be delighted to read fantasy stories set within their culture. On the other hand, non-Jews might find the book exotic (not a bad thing for fantasy), but they will also find it easily accessible, with most concepts taken from Judaism explained for a non-Jewish audience. (It doesn’t hurt that some ideas in fantasy come from Jewish mysticism: the idea, for instance, that magic derives from the power of words has its genesis in the Kaballah, as is mentioned in more than one of the stories in the collection.)

Making the Rounds takes old ideas and makes them new and fresh. Highly recommended.