Today we are joined by Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA) Grand Master Michael Moorcock. Simply put, Michael is one of the most influential figures in the history of science fiction. As a writer, editor, musician, and publisher, he helped shape the industry. Some might suggest that if Hugo Gernsback gave birth to science fiction and John W. Campbell gave it life, Michael helped make it human. When he took over editing New Worlds magazine in 1964, he helped start a revolution. The revolution, later tagged the New Wave, has forever left a mark on the science fiction industry.

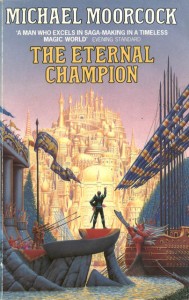

Michael’s boundless imagination as an author produced Elric of Melnibone, one of the most iconic characters in the history of fantasy, as well as Jerry Cornelius and countless other memorable characters. His fiction explores the limits of traditional genres, challenging the boundaries between science fiction, fantasy, and popular literature. His creation of the Multiverse and his examination of the Eternal Champion has entertained, enlightened, and inspired readers across seven decades. He even managed to translate his fiction into music, collaborating with the bands Hawkwind, The Deep Fix, and Blue Oyster Cult.

Michael has won four August Derleth Fantasy Awards, a Nebula, a John W. Campbell Award, a Guardian Fiction Award, and a World Fantasy Award. He has received the World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement, the Prix Utopiales “Grandmaster” Lifetime Achievement Award, and the Bram Stoker Award for Life Achievement in Horror. Michael has also been inducted into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame. When not staring reality in the eyes, Michael spends his existence surfing new waves across the strands of Radiant Time.

Photo by Betsy Mitchell

R. K. TROUGHTON FOR AMAZING STORIES: Welcome to Amazing Stories, Michael. You started editing and publishing your own fanzine as a teenager. By the age of seventeen you were editor of Tarzan Adventures and soon after coeditor of Sexton Blake Library. Please tell us how you came into editing as a teenager and what life was like for you back then.

MICHAEL MOORCOCK: Well, I think my story is a fairly familiar one in that I started by publishing fanzines. My first fanzine was called Book Collectors’ News and was mainly for collectors of what in England are called ‘story papers’ and in terms of basic content were not all that different from the US pulps except ours were weeklies and often contained (as British comics would later) a variety of serials but could be focussed on a particular series. In the UK this was often that oddly British phenomenon the school story in which a group of regular schoolboy characters at a boarding school modelled on Eton or Rugby interacted or else had adventures off-campus. My favourite magazine was Union Jack which had come, by one of those strange but familiar processes, to feature only long weekly stories about the detective Sexton Blake.

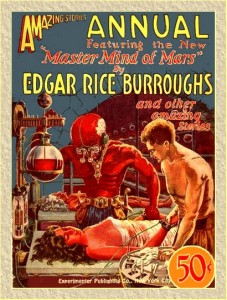

The second fanzine, which I published concurrently, was called Burroughsiana (actually misspelled Burroughsania by my 14-year-old self and appearing thus for its early issues). That was an Edgar Rice Burroughs fanzine. I knew nothing at that point about the world of SF fanzines and it was only through SF fans hearing about Burroughsiana that I came to discover those fanzines and, of course, a whole world of SF and fantasy. I made many new friends through the SF fanzines but at first had no interest in science fiction, apart from Burroughs. It took quite a while before I found a kind of SF I liked and that was typically in the pages of Galaxy where I discovered writers like Dick, Bester, Sheckley, Pohl and Kornbluth and so on. When I was 16 I interviewed for Burroughsania the editor of Tarzan Adventures, a weekly magazine using both strip (from the US Sunday pages) and text stories and features. The editor didn’t like my piece but the assistant editor contacted me when he was promoted to editor and asked me first for some articles about ERB and then for some fiction in the manner of Burroughs. He then told me he planned to leave the magazine. If I would like to join as assistant editor, when he left I would automatically have the chance to be editor and try out my own policies.

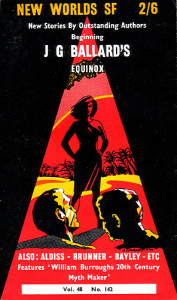

By 17 I was the editor, producing what was effectively a young adult pulp magazine with the Tarzan serial at the front and a lot of sf and fantasy, as well as features, in the second half! The circulation rose dramatically and I still know people today who were introduced to SF and fantasy through TA. Meanwhile, in BCN, I had supported a policy change by the editor of the last remaining publication to feature Sexton Blake, publishing two book-length magazines a month, Sexton Blake Library, published by the vast international publishing empire IPC. Eventually that editor, Bill Baker, invited me to join as assistant editor. By the age of 19, I was a fully experienced editor but also involved in The National Union of Journalists who didn’t really know how to classify me. I had enough years to qualify serving as an officer on the local chapter committee but wasn’t technically old enough! While there, I began to sell shorts to the New Worlds group, including SF Adventures and Science Fantasy. I had a strange time at IPC. The final blooming of magazine publishing as the dominant form of entertainment. I eventually left SBL to work on Current Topics, a Liberal Party policy magazine, when I was 21. At the same time I freelanced, writing features on almost every topic and comics and juvenile fiction of almost every kind. I sold my first Elric story when I was 21 but was somewhat frustrated with the general approach of most SF and fantasy, although the quality in Galaxy was I thought, generally high. I began to think, along with my friends Barry Bayley and J.G.Ballard, that a new form of fiction could be developed from SF which would engage with reality in a way which contemporary literary fiction did not.

By 17 I was the editor, producing what was effectively a young adult pulp magazine with the Tarzan serial at the front and a lot of sf and fantasy, as well as features, in the second half! The circulation rose dramatically and I still know people today who were introduced to SF and fantasy through TA. Meanwhile, in BCN, I had supported a policy change by the editor of the last remaining publication to feature Sexton Blake, publishing two book-length magazines a month, Sexton Blake Library, published by the vast international publishing empire IPC. Eventually that editor, Bill Baker, invited me to join as assistant editor. By the age of 19, I was a fully experienced editor but also involved in The National Union of Journalists who didn’t really know how to classify me. I had enough years to qualify serving as an officer on the local chapter committee but wasn’t technically old enough! While there, I began to sell shorts to the New Worlds group, including SF Adventures and Science Fantasy. I had a strange time at IPC. The final blooming of magazine publishing as the dominant form of entertainment. I eventually left SBL to work on Current Topics, a Liberal Party policy magazine, when I was 21. At the same time I freelanced, writing features on almost every topic and comics and juvenile fiction of almost every kind. I sold my first Elric story when I was 21 but was somewhat frustrated with the general approach of most SF and fantasy, although the quality in Galaxy was I thought, generally high. I began to think, along with my friends Barry Bayley and J.G.Ballard, that a new form of fiction could be developed from SF which would engage with reality in a way which contemporary literary fiction did not.

ASM: Before your 25th birthday you were named editor of the British magazine New Worlds. Since that day, science fiction has never been the same. Until that point the industry had predominantly held to the Campbellian blueprint. You, along with some of your contemporaries, decided it was time for change. Some might suggest that it wasn’t a conscious decision at all but rather an organic difference in artistic tastes and sensibilities. Together you incited a New Wave of science fiction. Please take us back to that first day on the job. What was going through your head, and what did you hope to accomplish?

MM: Yeah, it wasn’t long after my 24th birthday actually that Ted Carnell, the editor for whom I was writing (Elric, The Eternal Champion, The Sundered Worlds) told me the magazines were folding. I had already written several articles for Carnell in which I suggested where sf/fantasy could go, so when Science Fantasy and New Worlds were bought, by Compact Books, Carnell suggested I take over from him (because of my editorial experience). Meanwhile Kyril Bonfiglioli, a friend of Brian Aldiss and the new publisher, asked to become editor. He had no experience. I was allowed first choice and to some peoples’ surprise chose New Worlds. I felt there was more I could do with the title. I wanted a large size magazine on art paper so I could publish contemporary painting and sculpture as well as scientific features to produce a blend of art, science and fiction. Compact told me they couldn’t budget for anything more than a paperback size on fairly pulpy paper! It was probably for the best! My first editorial referred to William Burroughs, whose own fiction drew on SF, and whom I knew by that time. A New Fiction for the Space Age, I believe it was called. I got Ballard to write our first serial and a guest editorial. Barrington Bayley, who later became a sort of icon for cyberpunks, also contributed. I soon realised there were not many writers out there ready to produce the new kind of fiction I visualised. I had to proceed slowly to develop not only the fiction I wanted but also the kind of readership I needed. Much of the early work in my New Worlds was fairly conventional, if aspiring to a slightly more ambitious level of writing. Gradually new writers began to emerge an old ones became increasingly ambitious. I published a lot of young Americans who had been given their first breaks by Cele Goldsmith at Amazing and Fantastic.

Rather innocently, I had thought most SF readers would welcome the idea of a new kind of literary fiction coming out of science fiction! Fandom, at least, didn’t. Neither did the likes of Fred Pohl, then editing Galaxy, whom I admired.

ASM: Famously, lines were drawn between the science fiction traditionalists and the revolutionaries. Editorials, reviews, and speeches were devised to both condemn and support the New Wave. What was life like in the trenches during the early years of the transformation?

ASM: Famously, lines were drawn between the science fiction traditionalists and the revolutionaries. Editorials, reviews, and speeches were devised to both condemn and support the New Wave. What was life like in the trenches during the early years of the transformation?

MM: Schizophrenic was what it was like! I thought SF readers, of all people, would be open-minded and welcome innovation! At first most of my support came from the non-fandom world of regular newspapers and journals. As I said, I was a little surprised. I received quite a lot of negative mail from ‘old guard’ SF readers who felt we were somehow attacking ‘their’ SF. At a big conference about what was being called ‘The New SF’ in 1968 attended by philosophers, poets and arts professionals as well as writers, Mike Kustow, the former director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, who had brought in innovations during his term there, said he called it the ‘anxious ownership’ syndrome. People somehow thought we were trying to ‘take away’ the SF they enjoyed. Of course this was not the case. What we were trying to do was broaden what could be done in fiction by using some SF conventions. I certainly didn’t want to see ‘old school’ SF writers, many of whom were my friends, put out of work and that of course didn’t happen. Far from it. In fact we were a bridge from conventional fiction to SF.

But tempers were raised at SF conventions to the point where I stopped going. Don Wollheim, a friend of mine who published me, one year delivered my Nebula award for Behold the Man at my house where we had a long, friendly chat. A couple of days later I was in the audience at a convention when he condemned me as a ‘pseudo-intellectual’ bent on destroying SF. I got up and left and thereafter wouldn’t take part in any further debates. We weren’t trying to take anything away from readers. In fact we were adding to the tool box, broadening what sf could do. General readers became interested. Our circulation rose considerably. We helped improve the image of SF, so everyone benefitted. By the time I went to large format we had substantially broadened our readership. My main interest was not so much to change SF as to use SF to improve what fiction could do. Contemporary ‘litfic’ was bogged down in decayed modernism. SF had developed alongside modernism, occasionally borrowing its techniques. Now so many SF methods are used in the ‘mainstream’ that it seems everyone benefitted. We brought new techniques and improved levels of ambition to SF and SF did the same for literature in general. Who lost ?

ASM: The previous editor of New Worlds, John Carnell, had published some of your stories and letters in the magazine. Many considered Carnell to be a well-respected editor with an eye for a good story. How exactly did the editor’s chair pass from Carnell to a young visionary?

MM: Sorry, I jumped the gun on this question. See above. I had a very amiable relationship with Ted (from his middle name) who had recommended me as his successor, presumably agreeing in general with my ideas published in New Worlds and Science Fantasy! That’s why he recommended me as his successor.

ASM: The 1960s were a period of change and of questioning the old guard. What influence did the culture of the day have on what you were trying to explore as both an editor and an author?

MM: For us it was considerable. But it went both ways. Cross pollination. Thanks to Brian Aldiss, we received a grant from the prestigious Arts Council (equivalent to the National Endowment for the Arts). The British pop art movement, which began a little sooner than the American movement, drew considerably on SF. Those artists were appearing in New Worlds, too, as soon as we had the size and paper quality (by 1967). We shared contributors and facilities with the ‘underground’ press — IT, Frendz and Oz in particular. The same poets, like D.M.Thomas, Peter Redgrove and George MacBeth, were appearing in NW as in the avant garde journals of the day. Contributors who appeared in New Scientist appeared in New Worlds and so on. One of the leading art magazines of the day, Ambit, shared many contributors with us. Experimental film-maker Steve Dwoskin was a guest editor. Eduardo Paolozzi, the sculptor and print-maker was on the masthead as Aeronautics Advisor. Many of us were open to all the ideas in the atmosphere in those days. At a party you would find Arthur C. Clarke deep in conversation with William Burroughs, Judith Merrill talking earnestly to Angus Wilson (then considered a leading literary novelist of the day), the poet Christopher Logue talking to our science editor Christopher Evans etc. etc. Musicians, painters, writers were constantly meeting (at the New Worlds lunches for instance). For some reason there were fewer barriers than seemed to exist in the US at the same time.

ASM: Your passion for New Worlds led you to take over publishing the magazine when the owners ran into financial difficulties. As the 1970s began, the magazine industry shifted and New Worlds, along with countless other magazines, was forced to end regular publication. After one of the most influential decades in any magazine’s history, the New Wave’s standard bearer was lost. Looking back on your run at New Worlds, how do you view the success of the magazine compared to your original goals?

MM: The original publishers’ distributors went bankrupt. That’s when I saw the chance to take over (with the Arts Council’s help) and use the format I’d first visualised! It’s very hard to say, of course, what our success was because you don’t know what would have happened anyway. But it did seem that by the 1980s many of our goals had been met. SF and popular culture were interacting considerably with academia as well as ‘high’ art. The barriers were often down. By the 1970s books by Ballard and myself, which might once have been marginalised, received literary prizes. Books by literary writers increasingly contained SF elements. Would that have happened anyway? Who knows?

ASM: How do you view the impact of the New Wave on today’s science fiction?

MM: As I say, I think we added to the toolbox quite a bit and we set higher standards so that much that is published as sf could easily have been published as literary fiction and vice versa. Everyone benefitted. Authors’ ambitions rose all round.

ASM: My first introduction to your fiction was through Elric. From the very first novel I picked up, I recognized there was something different and remarkable in your writing. I could sense a depth and richness that I found rewarding. You have described yourself as someone who is not a world builder. You are hesitant to put labels on your fantasy, resisting some of the labels pushed on you by others. What are the origins of Elric, and how would you describe the tales you’ve written about him?

ASM: My first introduction to your fiction was through Elric. From the very first novel I picked up, I recognized there was something different and remarkable in your writing. I could sense a depth and richness that I found rewarding. You have described yourself as someone who is not a world builder. You are hesitant to put labels on your fantasy, resisting some of the labels pushed on you by others. What are the origins of Elric, and how would you describe the tales you’ve written about him?

MM: The Gothic novel was a big influence — Maturin, in particular. Dissatisfied with where it seemed to be going I went back to the roots of fantasy, before it became a genre just as I’d done with science fiction (see my book Wizardry and Wild Romance). I’d recommend the process to any writer wanting to produce a particular kind of fiction. The problem with any genre (and I think ‘litfic’ is just as prone to this) is that you get a kind of xerography going on, because one author is inspired by and imitates the authors they admire, whereas the further back you go to roots the greater the likelihood of your creating something fresher. I was influenced by mythology and the great Romantics, Wordsworth, de Quincey, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley and Mary Shelley, the Brontes and so on, using techniques where for instance the landscape and the weather is carefully employed to describe and illustrate internal conflicts within a character. I don’t build worlds because the worlds I describe reflect the character. Landscapes are there to reveal what’s going on in the characters’ minds. On a melodramatic level you find it in all James Whale’s fantastic movies. I’m not very interested in, say, the GNP of Melnibone! I don’t mind if others enjoy playing that sort of game but it’s not of much interest to me. Characters and their moral conflicts interest me.

ASM: Some may not know that across much of your fiction you have created a Multiverse, an existence that transcends place and time. In many of these stories, you have introduced the Eternal Champion in one form or another. For those not familiar with your work, please explain this overarching story line and what they might discover.

ASM: Some may not know that across much of your fiction you have created a Multiverse, an existence that transcends place and time. In many of these stories, you have introduced the Eternal Champion in one form or another. For those not familiar with your work, please explain this overarching story line and what they might discover.

MM: Well, it goes back to two of my earliest stories for Carnell around 1962/3— The Sundered Worlds in which I introduced the term ‘multiverse’ to describe multiple universes existing as it were intratemporally and a human champion who is constantly reincarnated across that multiverse, over and over again. The third idea, from the Elric stories, is that of a ‘Cosmic Balance’, a regulating system in which the opposing forces of Law and Chaos are in conflict. I don’t use ‘Good and Evil’ as terms in this struggle. The eternal hero or heroine exists to fight either for Law or for Chaos so that neither ever gains ascendancy. These forces also struggle within them. I also introduced in later books the notion of Radiant Time and of Space as a dimension of Time. In the first Eternal Champion story the hero is an ordinary man, John Daker, called across the multiverse to fight for the human race. In the course of the story he discovers that the human race has committed a great sin against a non-human race and so changes sides in order to set matters right. This in turn causes him great guilt. At other times some version of Daker fights for Law or Chaos in order to set the balance straight. The story can be a supernatural adventure, a ‘surreal’ story as in Jerry Cornelius, a piece of modernist fiction or an ‘ordinary’ story with few imaginative elements. The story can be symbolic, realistic, allegorical or, as in The War Amongst the Angels stories any combination of those elements.

ASM: When I read your fiction, I always feel like I should be looking out of the corner of my eyes to glimpse the unseen—to find that hidden treasure meant to reward the truly diligent. What extra dimensions are hidden within your fiction that you feel have largely gone unobserved?

MM: Oh, there are always little extras in almost everything I do, whether it’s simply a name or two or a bit of parody or whatever. One of my other ambitions doing New Worlds was to pack as many narraties as possible into one piece of fiction. The Cornelius stories do that. Ballard’s ‘condensed novels’ in The Atrocity Exhibition did that. There’s also a certain amount of game-playing between myself and the reader I have always written ambitious fiction on the assumption I’m being read by a smart, imaginative reader. I like to offer a sort of reflecting crystal ball into which that reader can stare and use their own creativity to add further dimensions, extra narratives to what I’ve done. Reference to one character bring up all the stories associated with that character. The character can be mine or a real person. Writing fiction is, like writing music or films, always a collaborative process with the audience. The simpler stories don’t offer as much as, say, the Jerry Cornelius stories, but there’s always a certain amount of material intended to mirror the readers’ own inventiveness and refer to multiple narratives.

ASM: Many of us can point to a single story or book that hooked us on science fiction for life. What was your first introduction to imaginative fiction?

ASM: Many of us can point to a single story or book that hooked us on science fiction for life. What was your first introduction to imaginative fiction?

MM: The Master Mind of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs. When my father fled the family home Christmas Day 1945 he left five books behind. One was that ERB book, another was Son of Tarzan and another was The Apple Cart by George Bernard Shaw. The others were boys’ books he’d won as school prizes. One was The Constable of St Nicholas by Edward Lester Arnold. For years I thought to be a proper writer you had to have three names. My early work was always signed ‘Michael J. Moorcock’… The first book I bought with my own money was The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan. Reading that made me think a book had to provide at least two meanings and not just be ‘a story’. The first ‘modern’ SF book I read was The Stars My Destination by Alfred Bester. That was when I realised what SF could do. I bought it in Paris when I was 16.

ASM: What authors and editors have most influenced you?

MM: Well, obviously the ones listed above. Mervyn Peake and his wife Maeve all but adopted me when I was young. He was a massive inspiration. I can’t think of an editor who influenced me. Prose writers include Maturin, Dickens, George Meredith, R.L. Stevenson, Rudyard Kipling, H.G.Wells,, Aldous Huxley (though I’ve never read his SF), Elizabeth Taylor, Elizabeth Bowen (never read her supernatural fiction!), Angus Wilson, Albert Camus, J-P Sartre, William Burroughs, Ronald Firbank, Celine, Boris Vian, Alfred Jarry, Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Leigh Brackett, Gerald Kersh, John Lodwick… I feel as though I’m an accumulation of all those and more.

ASM: You’ve mentioned previously that Mother London is the favorite novel you have written. Many consider it to be a literary masterpiece. It was even short-listed for the prestigious Whitbread Best Novel Award given to books that exhibit literary excellence. Please share with us your view of Mother London, and describe the elements which make it so powerful.

ASM: You’ve mentioned previously that Mother London is the favorite novel you have written. Many consider it to be a literary masterpiece. It was even short-listed for the prestigious Whitbread Best Novel Award given to books that exhibit literary excellence. Please share with us your view of Mother London, and describe the elements which make it so powerful.

MM: I wrote that novel between volumes 2 and 3 of my ambitious literary sequence known as the ‘Pyat Quartet,’ an attempt to expose the many elements which created the Nazi holocaust. Concentrating on that subject had made me so depressed I decided I needed to write a novel which celebrated the things I loved in life, especially London, the city of my birth. To describe the many elements from the whole world which went into the creation of modern London I used the device of characters who could, perhaps, pick up telepathically all the voices of the city. That is really the only imaginative element of the novel and some people have chosen therefore to describe it as an sf novel, which it isn’t, though it does precisely what I had always wanted to do with modern fiction and that is incorporate elements taken from sf into its general structure. The other imaginative element is the reference to the ‘miraculous’ and how it has affected the lives of the three main characters (defusing an unexploded bomb during the Blitz, escaping a burning building, also during the Blitz, escaping a V2 rocket during the final Nazi bombardment of London etc.) but essentially the book is a celebration of ‘ordinary’ human courage, love and resilience and covers the same period of London echoing my own life until the abuse of those qualities during the post-war world I knew by those elements represented by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, leading particularly to the commercialisation and consequent simplification of our history. When history is used to ‘sell’ a city or place as a product, then simplification and sentimentalisation necessarily come into play to abuse memory. Real myth is the opposite of that abuse. It enriches and perpetuates memory, it helps us survive. I think people pick up on the resonances in the novel and that’s why it seems to have kept an audience. I think one of the other two novels nominated for the Whitbread in 1988, which won, Satanic Verses by Rushdie reflected on similar themes.

ASM: As someone who has worked across seven decades in the science fiction and publishing industries, how have science fiction and publishing changed during that time?

MM: Not as much as I hoped SF might in 1965. I wanted more experiment. Others wanted to see SF brought into line with modernism. That’s probably happened. As for the majority of sf writing there was a period when publishers were far more willing to try all kinds of off-beat titles, back all experiment, but you don’t get best-sellers that way. Once they, and certain authors, understood what was popular with the average middle-brow reader you started getting a lot more average titles published. Average is always rewarded in the arts, popular or otherwise. This might make good money but rarely makes outstanding SF. Publishers now have rules about what constitutes SF. Idiosyncratic editors are increasingly discouraged. The off-beat finds it harder to be published by powerful publishers. The discontented reader starts looking elsewhere for what is original and different. The standard of writing and characterisation in generic science fiction has risen high enough to interest the middle-brow reader but in the main (and there are of course exceptions) if it’s going to be a generic best-seller it’s unlikely to be a very original book. I was attracted to SF for its potential to do something amazing. Too little generic SF amazes, these days, at least in the long form. But it hardly matters, I think, because, as I’d hoped, so much literary fiction utilises SF elements that much of the best imaginative fiction isn’t published as genre (Atwood, Chabon, McCarthy etc). Indeed, in reality the distinction between literary fiction and science fiction has disappeared and the demanding reader is certainly less likely to be put off a book by the category in which it’s shelved.

ASM: With the sheer volume of imaginative fiction being published today, do you think it is possible for a single author, editor, or publisher to have as much influence over the industry as John W. Campbell or New Worlds once had?

ASM: With the sheer volume of imaginative fiction being published today, do you think it is possible for a single author, editor, or publisher to have as much influence over the industry as John W. Campbell or New Worlds once had?

MM: I think an academic like Leavis or a magazine like Scrutiny had a huge influence on fiction in general so there’s no reason another academic, editor or publisher shouldn’t emerge to influence non-generic imaginative fiction. But I doubt that a magazine published in the SF genre is likely to have as great an influence on that field in these times, partly because the commercial circumstances have changed. In that sense, I think, the revolutions were successful and certainly did what I set out to do, which was to incorporate the best elements of SF into the mainstream.

ASM: If you could outline and define the next wave of science fiction, what would it look like?

MM: I suspect we’re reduced to little more than fashions, like steam punk, which I enjoy. And maybe none the worse for that. But who can accurately predict fashion?

ASM: Your novel The Final Programme was made into a feature film in 1973. Famously, you had some disagreements with the producers over the direction of the film. Later, in 1974, you collaborated on the film The Land that Time Forgot. Again, your views were not shared by the filmmakers. More recently, Paul and Chris Weitz optioned your Elric stories for what they plan to be a trilogy of films. What is the status of the Elric films, and how have your experiences in filmmaking prepared you for this latest undertaking?

MM: My disagreements had to do with the dumbing down of both movies. For years I refused to let anyone consider making a movie from my work. At present there are several people currently interested in taking Elric to the screen. Until recently I wasn’t altogether happy with what was presented to me as a way of adapting Elric or any of my other fantasy characters to film or TV. If I were involved I would concentrate on the characters and the interplay between them since we are now able to achieve pretty much anything we want in terms of effects. I would put a stronger ‘back story’ into Melnibone and its inhabitants. If Game of Thrones has shown us anything, it’s that ‘the marvellous’ is no longer enough to hold an audience. The human element is just as important. Happily, I always tended to concentrate as much on personalities as marvels, so I’m currently looking for a producer and/or director willing to deal with character at least as much as the imaginative elements. I have talked to one or two. I think we might see some interesting developments in future.

ASM: Recently Michael Moorcock’s New Worlds has emerged on the internet as a new source for everything science fiction. What is your involvement in the project, and how are things going with this new endeavor?

MM: Honestly, I have no idea! I didn’t know they were going to call it ‘Michael Moorcock’s’ New Worlds. I gather there were disputes between those who wanted to launch the project and I haven’t seen the result. I suspect there won’t be a second issue. Magazines like New Worlds are created by a perceived need, not from nostalgia for a better time! A few years ago I satisfied my own editorial instincts by being one of the editors of Fantastic Metropolis. I was still interested, as now, in creating that cross-pollination. By the likes of Alan Wall, for instance, a modernist novelist and academic who studied physics and recently began to publish in Asimov’s. Currently, I advise the odd publisher and promote the odd book or author that I admire and that’s all I need to feed my inner editor! If I did NW now it would take advantage of everything we can now do. I would love to produce a magazine publishing the likes of Wall, Iain Sinclair (who appeared in the last issue of NW I produced in 1996), Alan Warner, Steve Aylett, China Mieville and some of the younger experimenters whose work I occasionally see. There are poets and graphic artists I would include. If I did it online I could produce graphics, film, music and speech, too, all combining to produce original and stimulating kinds of fiction, but I’d need very good tech help, financial backing and probably a lot more time than I’ve been allotted! And it probably wouldn’t be fiction as we know it, Jim.

ASM: Fans have always played such an important role in the development of science fiction. Having grown from a young fan with your own fanzine to one of the icons of the industry, how do you view the importance of science fiction fandom?

ASM: Fans have always played such an important role in the development of science fiction. Having grown from a young fan with your own fanzine to one of the icons of the industry, how do you view the importance of science fiction fandom?

MM: Well, when I was producing fanzines sf conventions used to be attended by scores or at most a few hundred people. I was recently looking at my programme for the 1957 world convention. The list of events filled half a page! Now the size is so much greater, with thousands attending and events streamed across dozens of pages. That means there are a number of different ‘fandoms’ within the greater one. As anyone who visits my website will see, I still think readers are of paramount importance, but increasingly the emphasis is on media other than text and I find it hard to comment on those. I doubt if modern fans see themselves as being a tiny marginalised minority the way they did in 1960. They could hardly do so since it seems most of the movies made in Hollywood and most network TV series launched are fantastic in nature. I suspect ‘fandoms’ of the kind I started in will continue to emerge but they might not coalesce around science fiction in general (just as cyberpunk or steampunk don’t). I suspect the new fandoms will be characterised much as the preRaphaelites or Dadaists were defined, as small, influential groups initially in the margins. As such they’ll continue to be very important.

ASM: You were a member of the Swordsmen and Sorcerers’ Guild of America. The other founding members included Lin Carter, Poul Anderson, L. Sprague de Camp, John Jakes, Fritz Leiber, Andre Norton, and Jack Vance. How did this group come about, and what was your experience with it?

MM: I wasn’t really a founder. I was told I was a member by Sprague, whose brainchild it was! I don’t think it did much but occasionally meet at conventions. I never attended a meeting because most of them were in the US when I was in the UK!

ASM: Looking back on your career so far, what makes you most proud or satisfied?

MM: Maybe that I appear to have written a couple of decent books, put a few new words or phrases into the language, created a few enduring characters and had a minor influence on the direction of imaginative literature. Mostly I’m proud that I haven’t screwed up too badly as a father to my children, a husband to Linda, a loyal friend to my friends. I encouraged and promoted some very talented writers. I’m proud of some of the music I’m still doing, recording these days in Paris. I feel I could have done a lot better in all those areas and I’m going to keep on trying.

ASM: Over the years you have created so many memorable characters and stories. Some of your fans are urging me to suggest more Bastable stories. What are you working on now that we can look forward to seeing in the future?

ASM: Over the years you have created so many memorable characters and stories. Some of your fans are urging me to suggest more Bastable stories. What are you working on now that we can look forward to seeing in the future?

MM: Those characters all live on in my head. Their stories continue to resonate through the multiverse! The eternal struggle is never over! With The Whispering Swarm, my new novel, I’m trying to investigate the appeal of fantasy and the way I might have used it to escape from moral responsibility as a young man. The book is also a memoir and has historical elements. I’m not likely to revisit old characters in entire novels, but I do bring them back where their particular narrative can improve the general one. I did that with Bastable in the last Elric/Eternal Champion novel which began with The Dreamthief’s Daughter (Daughter of Dreams). The fiction I’m currently writing tends to emphasise character and moral examination. Stories, which appeared in Stories, edited by Gaiman and Sarrontonio, is closer to much of what I’m writing apart from Jerry Cornelius stories like The Grenade Garden which I’m still writing in direct response to current events. This includes two recent stories in the ‘Third World War’ sequence I began with Crossing into Cambodia. They are Kabul (set in the near future) and Staying in Rome (set in the near present). Another short novel I’m working on, Stalking Balzac, also deals with my life as it actually was rather than the one I imagined! But I have so many stories still crowding to get out of my head, I can’t say there will never be another Bastable novel, or indeed another Elric story (in fact I’m currently planning one to be done as a comic). My new songs refer to The War Amongst the Angels and the Game of Time.

ASM: Thank you for joining us today. Every fan of imaginative fiction cannot help but glimpse your fingerprints all across the industry. We are grateful for your courageous efforts in discovering new pathways for our minds to explore. Before you go, is there anything else you would like to share with the readers of Amazing Stories?

MM: That’s very kind of you. Thanks. All I have to say is that while imaginative fiction supplies us with great escapism, which we all need to take our minds off the daily grind, I have always believed that the best science fiction and fantasy is most valuable when it confronts important issues of the day. It isn’t surprising that we are currently living in a world imagined by the great sf writers of the 1950s and 1960s who concentrated on contemporary issues of their time and by doing so were able to anticipate so many of the social and moral problems we face today. They achieved what they did by looking at reality with a hard, critical eye and I think we need to do that even more today. From H.G.Wells onward the best sf has refused to turn away from reality. To remain vital and worthwhile it has to continue to expand its range, maintain its critical and analytical qualities, and, where possible, to improve its techniques, which is frequently achieved through experiment as well as spirited debate. It is up to editors and publishers to encourage and applaud innovation. In that way SF will continue to make its creators and writers proud of their chosen form.