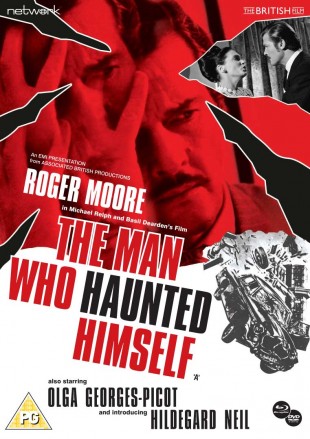

The Man Who Haunted Himself is, as the title suggests both a ghost and a doppelgänger story, and as such is a rather unique tale of the uncanny, unfolding perhaps much as one might imagine a feature-length, British Twilight Zone. The film starts with business man Harold Pelham (Roger Moore) leaving his London office and driving west out of the city, but then…something happens to him. He starts to speed, driving ever more recklessly. There are shots of another, sportier, car, superimposed over his staid family saloon. The scene resolves with a devastating crash and next thing, Pelham is in hospital, doctors fighting for his life. His heart stops briefly on the operating table, and when it restarts there are two traces on the ECG.

The Man Who Haunted Himself is, as the title suggests both a ghost and a doppelgänger story, and as such is a rather unique tale of the uncanny, unfolding perhaps much as one might imagine a feature-length, British Twilight Zone. The film starts with business man Harold Pelham (Roger Moore) leaving his London office and driving west out of the city, but then…something happens to him. He starts to speed, driving ever more recklessly. There are shots of another, sportier, car, superimposed over his staid family saloon. The scene resolves with a devastating crash and next thing, Pelham is in hospital, doctors fighting for his life. His heart stops briefly on the operating table, and when it restarts there are two traces on the ECG.

After leaving the hospital Pelham and his wife (Hildegard Neil) go to Spain to recuperate. It’s when he returns to work that his life gets strange. One colleague says he saw Pel the previous Wednesday in London, while he was still in Spain. Another refers to a snooker match the previous Thursday that Pel won, and a party they went to afterwards. He meets a young photographer (Olga Georges-Picot) who believes she went to bed with him a few days ago—all while he was still in Spain.

Meanwhile Pel is tasked with tracing the source of a leak in the engineering company at which he is a board member, and which is facing a possible merger/hostile takeover by a much larger company. Is everything part of an industrial espionage conspiracy? Though the title and the opening sequence mitigate against this, an 1970 an audience familiar with Moore from The Saint might be persuaded. Moore even gets the line, three years before Live and Let Die, ‘espionage isn’t all James Bond and on Her Majesty’s secret service you know.’ Or is there a more psychological explanation, the motorway scene indicating the beginning of some sort of middle-life crisis, a man facing serious difficulties both in the office and his marriage?

The Man Who Haunted Himself rather skilfully plays Moore both to and against type. The Pel we see on screen is almost exclusively a responsible, principled, honest middle-aged family man heading towards a breakdown, but is the strangeness he experiences the cause of his crisis, or a result of it? Seeing Moore playing a man descending into neurosis and becoming incapable of coping with the world around him plays completely against the smooth, ultra-competent ladies man, Simon Templer, aka The Saint, a character that had been a huge hit for Moore on television through most of the 1960s. Equally, while barely seeing Pel’s doppelgänger, we can imagine him out there in “Swinging 60s” London, enjoying the company of beautiful women in luxurious casinos and more intimate settings. A smooth, charming, perhaps even ruthless man.

If The Man Who Haunted Himself takes a misstep, it is in the late introduction of Freddy Jones as a psychiatrist. He seems to think he is in a different sort of film than everyone else, or perhaps didn’t care and just decided to eat the scenery. With mad scientist hair, dark glasses, and exaggerated mannerisms he seems to be channeling Dr. Strangelove, or any number of other loony 60s screen psychiatrists, always far madder than their patients. Fortunately he is not in the film long, and everyone else provides fine support. But it is Moore’s film—he has stated that it was his favourite role—and it is a shame that he did not get offered, or chose to make, more dramas that would have pushed him like this. The Man Who Haunted Himself provides a rare glimpse of Roger Moore as a really fine actor, suave and assured but also deeply troubled, tormented, angry, and haunted.

*

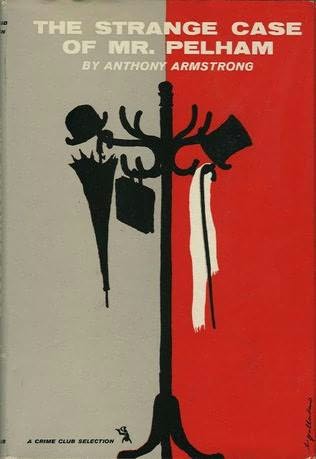

The Man Who Haunted Himself may be a little slow by modern standards. What 1970 film isn’t? But then, it may have seemed slow when it was new, being expanded from a much shorter television original. The screenplay was written by director Basil Dearden, Michael Relph, and an uncredited Bryan Forbes, and was based on Anthony Armstrong’s 1957 novel, The Strange Case of Mr Pelham, which in turn was based on a 1955 BBC television play called ‘The Case of Mr Pelham,’ written by Armstrong from an idea by Ian Messiter and Duncan Ross.

The Man Who Haunted Himself may be a little slow by modern standards. What 1970 film isn’t? But then, it may have seemed slow when it was new, being expanded from a much shorter television original. The screenplay was written by director Basil Dearden, Michael Relph, and an uncredited Bryan Forbes, and was based on Anthony Armstrong’s 1957 novel, The Strange Case of Mr Pelham, which in turn was based on a 1955 BBC television play called ‘The Case of Mr Pelham,’ written by Armstrong from an idea by Ian Messiter and Duncan Ross.

But, the play itself has a doppelgänger.

Better known than the BBC production is a 24-minute-long episode, also called ‘The Case of Mr Pelham,’ of the American anthology series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, directed by Hitchcock himself and first broadcast on US television on 4 December 1955. This version stars Tom Ewell as Mr. Pelham, has a teleplay by Francis Cockrell, and again, as the credit card reads, is ‘based on [the] story by Anthony Armstrong.’ So the story began on the BBC, went to American TV, was turned into a British novel, and then became a British feature film.

Better known than the BBC production is a 24-minute-long episode, also called ‘The Case of Mr Pelham,’ of the American anthology series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, directed by Hitchcock himself and first broadcast on US television on 4 December 1955. This version stars Tom Ewell as Mr. Pelham, has a teleplay by Francis Cockrell, and again, as the credit card reads, is ‘based on [the] story by Anthony Armstrong.’ So the story began on the BBC, went to American TV, was turned into a British novel, and then became a British feature film.

Not surprising given these origins that on one level the story seems stretched to breaking point, by cinema standards, at a relatively svelte 94 minutes. That’s because we are, certainly now, presumably then, way ahead of Pelham. We know that sooner or later he is going to have to literally confront himself, and we watch, waiting for the ramifications. But if you take the film as building up to that confrontation through a plethora of small but telling details, the joy comes in watching Moore’s performance as Pelham’s world disintegrates and he comes to realize, as much as anyone can in the realm of the uncanny, what is going on.

The film does build to a terrific dual climax—the eventual meeting of the two Pelhams—before everything comes full

circle back on the road. The final shots are chilling. The very last shot, over which the end credits play, delivers an extra, near subliminal shudder for those paying attention.

*

The Man Who Haunted Himself was released in 1970 to critical derision and a poor box office. It was shown on BBC television, usually after the 9pm news on Monday evenings, several times from the mid-70s onwards. This is when I first saw it, and like many of my generation, it lodged in my brain. It was one of the first ‘strange’ films I saw as a teenager, and though perhaps somewhat middle-of-the-road compared to other Brit horrors of the time like The Wicker Man or Don’t Look Now, it had an unforgettable power.

When Network released it earlier this year on a Blu-ray/DVD combo pack (what is the point of those? Who with a Blu-Ray would chose to watch a DVD?), I wondered if it would hold up. It does. I thought it might just be nostalgia, but it is much better than expected. The film still chills.

It is very skillfully directed by Basil Dearden. He helmed the classic ghost story The Halfway House (Ghostly Inn in the US), the classic horror Dead of Night, and other British classics ranging from The Blue Lamp, The League of Gentlemen, and Victim, to the Charlton Heston epic Khartoum. The cinematography is mostly workmanlike but occasional inspired. The editing, in key sequences, is first rate. Michael J. Lewis’ score is compelling, the jaunty main theme becoming a haunting element in the narrative itself.

The shots of London streets are a fascinating time capsule in themselves and the footage of the main road system west out of London as it was in 1969/70 is remarkable to see, both for how much it has changed and how much remains almost the same. Many of the buildings are easily recognized today, though some bear different corporate logos. For anyone familiar with the approach into London from the west, all of this adds extra fascination.

As to the Blu-Ray itself, the picture is excellent, looking so good it could almost have been shot yesterday. The level of detail is astonishing. A couple of optical-effects shots inevitably look grainy and soft, but they are essential to the story. There is a very thin white line that appears down the right hand side of the image occasionally, and it can be a little distracting. There is also some rare damage, a purple, and later, a yellow flaring briefly in the bottom right hand corner of the picture. Otherwise the image is as perfect as a mid-to-low budget 1970 film is likely to be. The mono sound is flawless.

The special features include the complete musical score, not as an isolated track, but effectively as a soundtrack album that can be selected from the extras menu. This plays for 34 minutes and makes up for the fact no official soundtrack album was ever released. Some of the score did appear on a rare ‘composer’s promo’ a few years ago. There is also a commentary track with Roger Moore and the celebrated British film director Bryan Forbes (an uncredited co-writer of the film) recorded in 2005 for a previous DVD edition. Finally, there are various galleries and PDFs of promotional materials. The Blu-Ray and DVD both include the film in its original 1.75-1 aspect ratio, and the DVD offers a bonus, and pointless, ‘maximum picture area version’ (eg. 1.33 ‘full frame’).

Note that the screengrabs in this review come from the DVD version and do not do the superb quality of the Blu-Ray justice. For unfathomable reasons the Blu-Ray constantly crashed my software when I tried to take screen captures. This has not happened with any other Blu-Ray, so is presumably the result of some particular feature of the disc.

Note that the screengrabs in this review come from the DVD version and do not do the superb quality of the Blu-Ray justice. For unfathomable reasons the Blu-Ray constantly crashed my software when I tried to take screen captures. This has not happened with any other Blu-Ray, so is presumably the result of some particular feature of the disc.

*

Note: The Man Who Haunted Himself was Bail Dearden’s final film in a career going back to 1939, when he directed the feature length thriller Under Suspicion for BBC television! His last screen work took him back to the small screen for three episodes of Roger Moore’s 1971 TV series The Persuaders!

Final spooky note for Halloween— The night I settled down to watch The Man Who Haunted Himself, my wife had gone out for a ladies’ dinner party at a friend’s house. When she came home, she casually mentioned that her friend’s husband returned during the meal and told her he had ‘just seen your husband’ sitting down by the beach looking out over the water. It wasn’t a joke. My wife had never heard of The Man Who Haunted Himself, let alone knew I was going to be watching it.

…is a freelance editor, writing consultant and story structure expert. To find out more, including hiring me to work on your writing project, read my profile or visit my website, To The Last Word.