At the heart of this debate is a real difference between how some creators of commercial art (i.e, art produced for the purpose of persuasion/marketing) view the kind of art they are commissioned to create, and how they view the art they create that no one is paying them to produce, what they call “personal works.”

It came as rather a shock to me – as a collector of illustration art – to discover that many of the artists whose illustrative works I admired used the term “image” to refer to the former kind of art, their commissioned, commercial “jobs”….and “art” to refer to the latter, even if those artworks contained the very same subject matter, was executed in the same style, and demonstrated the same painting techniques as their illustrative work. “Yes, that was a good image,” they’d say, when pointing at an original painting used for paperback cover, and “That’s one of my best paintings,” when pointing to the very same imagery, but an unpublished work. Confusing function with form, they applied the label image to their commissioned paintings without a second thought, viewing all such work as an audience might — as they perhaps were taught to do, by instructors and art directors. And in so doing, just re-inforcing the irrelevance of the “hired wrist” behind the image, whose self-expressive contribution to the work is rendered invisible by seeing it as a one-way communication. This is no more satisfying to me than so-called “fine” artists who consider themselves above (beyond?) real-world considerations like giving their works titles and/or feeling obliged to describe what they’ve created – it’s the same one-way communication! (as in “Who cares what they think? It is whatever you think it is! This is what I do! I MUST paint!!)

The Image is, of course, what people see when they see illustrative art reproduced…which historically has been practically the only way anyone COULD see it. That is to say, and unlike “Art” (capital A) – which might be seen in person, and found in galleries, public spaces, museums, and so on – illustrative art’s only “appearance” would be on a product: book, magazine, t shirt, puzzle, advertisement, toy package etc. As a result, how the physical art was created, what media was used, handled, or preserved after it had served its purpose (photographed and printed), or even if it was preserved, was immaterial. Once the “image” had been permanently captured, the “original” art was no longer needed, or necessary. And I think, so long as we viewed the art that way, serving a marketing function only, that is how the art was treated – indifferently, irresponsibly.

Only when such paintings were finally able to be viewed in their original form as Art, as physical objects which in all ways could be seen as genuine artwork, did fans and others begin to see the potential in them as ART worth respecting, and treasuring.

Behind labels such as “commercial art” and “fine art” stand a sad bias – a distinction (like low art vs. high art) that I thought was the sole province of the art elite – so it came as a surprise to discover that the same sort of bias had infiltrated the commercial art world, with terms like “image” and “imagery” taking the place of “art” and “artwork.” And it’s blinding artists to what they are losing by using those terms. Because today, there is largely ONLY imagery left to worry about – with very little, if any, physical art as back up. And the same thoughtlessness that resulted in thousands of paintings being lost or irretrieveably damaged, will affect virtual illustrative art. Given the rapid pace of changing digital technologies, far more effort and expertise will be needed to preserve these “images” than ever was needed for safe-keeping “traditional media.” Like a dark, dry closet. 🙂 Plus there is one important difference: Even if the images are saved and re-saved and re-saved through countless upgrades in hardware and software, they will STILL not be seen anytime soon in galleries, public spaces or museums…..a socio-cultural status that physical examples of illustrative art have finally, to some degree, achieved.

This is not to say that artists have had much of a choice, no matter what their aesthetic preferences, see Paint or Pixel. Noted artists, writers and experts in the field began using the word “image” to refer to illustrations just as soon digital technologies took over the publishing world. And, truth be told, many artists would not have survived the digital revolution had they not acquired the skills needed to compete in that computer dominated universe. As one artist wrote, in an email explaining his method “I recall that at Worldcon Boston (2004) you were urging me to paint the entire surface of my paintings, and I followed suit for a while, but then felt that there were parts that were better suited in their digital form, because they would never have turned out the way they did without the digital experimentation that begat them. But I have no regrets about creating hybrid digital traditional art, as I wouldn’t be in business at this point if I were non-digital, even if I had sold every original I’d created. Still, I have no qualms with collectors who steer clear of digital (art).”

What I found curious about this artist’s explanation (and gave me the idea for this post) is the way he referred to my urging to “paint the entire surface” – “as if” it is merely the (it is implied) mechanical application of paint to the entirety of a flat surface that is separating one created/constructed artwork (media outcome) from the other. That has always been one of the main differences between commercial artists and others…they must attend to, they are told to focus solely on, only half of what is a two-way communication: the “image” (the “visual effect”) To those who paint (and I believe, to those who collect) the processes themselves (the construction) is a distinctive element of the art, quite apart from (or is at least an important attribute of), whatever visual effect is created. The two, in fact, are inextricably combined, so that you can’t construct a painting differently and yet get the same visual effect – except through outright deception (as in simulating brush strokes or canvas texture).

The mindset that says “media is simply a means to an end” to my mind is confusing product with process. I think both are important. Those who want “paint” are expressing a perhaps outmoded view that there is something inherent in pigment applied by hand that is worth preserving and that thing, again perhaps, is one major component of originality (the hand that applied the paint). It’s part of, but not exactly the same as, what is meant by “visual signature”.

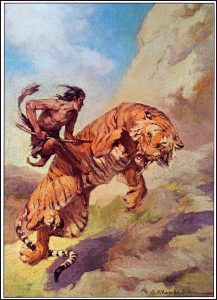

I see lots of digital artists struggling to express that sort of “originality” through digital techniques, and I’m not saying it can’t be achieved – or that in years to come we won’t be looking back at some artist working digitally today, and hailing him/her as the “Rembrandt” equivalent of the digital age, the “J. Allen St. John”/Frazetta/whatever of the 21st century. But speed and efficiency (“undo”) has a price, and that price (to me) is akin to the difference between handwriting and typing. You can get a great novel either way, but handwriting tells you something about the author beyond the excellence of the words, or the originality of the “voice” that strung them together.

That’s my view. Yours?

Recent Comments