A naked man recoils in surprise. He is surrounded by walls of glass; a strange apparatus is connected to his limbs by wires. Two men stand outside the glass, clad in purple robes. They stare at the imprisoned man, grave-faced, one rubbing his chin in thought.

A naked man recoils in surprise. He is surrounded by walls of glass; a strange apparatus is connected to his limbs by wires. Two men stand outside the glass, clad in purple robes. They stare at the imprisoned man, grave-faced, one rubbing his chin in thought.

It was winter 1928, and Amazing Stories Quarterly was giving its readers something to rub their chins over in turn.

Readers of the monthly Amazing Stories had long requested a faster publication rate. Now, editor Hugo Gernsback was fulfilling those demands with a sister title. Published less frequently but boasting a greater pagecount – space enough for a complete novel alongside the short stories, in fact – Amazing Stories Quarterly provided fans of Amazing with a way of getting more science fiction on a regular basis, at a time when SF magazines were still Gernsback’s private domain.

So, here are the stories contained within the Quarterly‘s debut issue…

“The Moon of Doom” by Earl L. Bell

In the twenty-first century, electricity has been entirely superseded by atomic energy, ushering in a new era. Fear of mutually-assured destruction has led to the worldwide outlawing of war. Technological advances have abolished avarice and want; medical science has overcome almost every disease; psychiatry has cured almost every criminal mind. The world should be a utopia, but it is instead gripped by a terrible realisation: Earth has begun to spin ever faster on its axis.

In the twenty-first century, electricity has been entirely superseded by atomic energy, ushering in a new era. Fear of mutually-assured destruction has led to the worldwide outlawing of war. Technological advances have abolished avarice and want; medical science has overcome almost every disease; psychiatry has cured almost every criminal mind. The world should be a utopia, but it is instead gripped by a terrible realisation: Earth has begun to spin ever faster on its axis.

Professor Ernest Sherard blames atomic energy for this state of affairs. He argues that overuse of this power source has left a residue – a “magnetic jacket” – around Earth. This magnetism has caused the Moon to drift towards our planet; this, in turn, has affected Earth’s rotation. He concludes that humanity’s only chance of survival involves abandoning all atomic energy immediately.

The world obligingly grinds to a halt, but it is too late: global cooling and catastrophic tidal disruption have set in, leaving humanity with mere months.

A side-effect of the Moon’s encroachment upon Earth is that the satellite absorbs some of the planet’s atmosphere; furthermore, the magnetic effect is not quite strong enough to make the Moon collide with Earth. This allows the last remnants of humanity to escape to the Moon in atomic planes – and the first to land are Ernest Sherard, his assistant Mildred Reamwe and the eccentric Professor Francis Burke.

The lunar colonists find evidence of an intelligent race that once lived on the Moon, including carvings that tell the story of the species: it was once similar to humanity but, facing climate change as a result of the Moon initially drifting away from Earth, descended into caves and commenced a different path of evolution.

Ernest, Mildred and Professor Burke explore a lunar cave together, and find themselves trapped. With them is a giant idol of the Moon-men’s monstrous god, He-She; this includes a death trap designed to kill sacrificial victims. To their horror, the three realise that this mechanism operates the exit – meaning that for any of them to escape, one must be sacrificed. The three bond in their last moments together, before the once-misanthropic Professor Burke decides to give his own life to save the others.

Ernest and Mildred escape back to the lunar colony, and later return to Earth, the axis having shifted sufficiently for the planet to be habitable once more. The two are now the Earth’s sole inhabitants: an Adam and Eve of a new era.

Earl L. Bell takes a florid writing style to his tale, offering a poignant depiction of civilisation’s collapse:

The soul of the City of Dementia, like its physical side, defied description. Albert Simmons, noted poet, called the place “The City of Unmasked Men,” and this was probably the most expressive epitome. The contentions of science that civilization was only a thin veneer, and that man was his real self only when released completely from social restraints or when facing death, was being proved in a graphic, piteous way.

The soul of man was stripped bare, revealing its paradoxes of good and evil, beauty and ugliness, virtue and vice, hope and despair. Paradox of love and hate, of avarice and benevolence, of vicariousness and selfishness, of spirituality and materialism—such was man in the city of his last stand. Insanity, perhaps, but sanity, too, is but a thin veneer. And the strangest paradox of all was man’s cupidity in his hour of travail, in the face of annihilation.

Once on the Moon the characters discuss poetry as much as science, contrasting the reality of lunar life with the role that Earth’s satellite previously played in the human imagination. When the protagonists reach the ruins of the extinct lunar civilisation, the prose takes on a Lovecraftian quality:

The central figure—the Thing—was fully three hundred feet high despite its sitting posture. Modeled in bold relief, it seemed a nightmare, something turned to stone. Though its features were plainly delineated, there was a suggestion of shapelessness throughout. It might have been an evil genie from Aladdin’s mystic lamp, or a shape from the nethermost pit. Its head—if head it might be called—was larger than its body. By far the most conspicuous feature was its eyes—great protruding radiant balls set high on a bulging brow and topped by what seemed to be spreading antennae. The orbs were at least fifteen feet in diameter, were faceted, and sparkled like a thousand diamonds. Its nose was a stubby porcine snout; its mouth an inordinate, many-fanged, flabby-lipped gash reaching almost from ear to ear and twisted in a Gargoyle grin, half smile, half leer. Its ears were huge fantastic appendages extending from the jowl below the level of the nose-tip. The lower part of the head, like the upper, was turgid, giving it the contour of the figure 8, of a plump peanut, rather. There was no neck.

The story falls back on convention for its climax, with the characters finding themselves in a stock H. Rider Haggard-esque scenario when they get trapped in the ruin. Despite this, the story on the whole is a wide-ranging and vivid depiction of planetary death and rebirth.

“When the Sleeper Wakes” by H. G. Wells

This is the original version of Wells’ novel, as serialised between 1898 and 1899, rather than the revised version published as The Sleeper Awakes in 1910.

This is the original version of Wells’ novel, as serialised between 1898 and 1899, rather than the revised version published as The Sleeper Awakes in 1910.

A Victorian man named Graham wakes up after spending more than two hundred years in a cataleptic trance. He finds that he is right in the middle of a social upheaval: a revolutionary group sees him as a messianic figure who will aid it in a struggle against the totalitarian White Council. The revolution is a success, and Graham finds himself the new ruler of the world alongside revolutionary leader Ostrog.

But the world he now rules is strange and new. It has cars capable of speeding at six miles a minute, fleets of advertising balloons dotting the sky, and portable devices that tell stories through moving images. Almost all towns and villages in Britain have been converted into vast hotels, while larger cities have grown bigger still, the public having pooled together to take advantage of centralised technology.

Graham begins to enjoy the opportunities afforded by this future society. He takes a trip in an aeroplane, surveying the new world from above. He is immediately consumed with enthusiasm for flight, at one point even trying to wrest control from the pilot. He also meets Ostrog’s niece, Helen Wotton – a love interest whose role Wells reduced in the 1910 revision of the novel.

Helen, it turns out, is no supporter of her uncle’s regime, and tells Graham about how the workforce is being oppressed. Graham approaches Ostrog with his concerns, only to be rebuffed by the revolutionary leader:

“What is their hope? What right have they to hope? They work ill and they want the reward of those who work well. The hope of mankind—what is it? That some day the Over-man may come, that some day the inferior, the weak and the bestial may be subdued or eliminated. […] And you would emancipate the silly brainless workers that we have enslaved, and try to make their lives easy and pleasant again. Just as they have sunk to what they are fit for.” He smiled a smile that irritated Graham oddly. “You will learn better. I know those ideas; in my boyhood I read your Shelley and dreamt of Liberty. There is no liberty, save wisdom and self-control.”

Graham decides to get a closer look at affairs by infiltrating the workforce in disguise. He finds religion given over to commercialism; news disseminated in dumbed-down form by “babble machines” (a precursor to Orwell’s Newspeak); children brought up in mechanised crèches, their mothers having joined the workforce; and the masses kept in line by thuggish police officers (who, in a blatantly racist touch, are all black). This is merely the middle class: Graham finds yet more squalor as he descends the social hierarchy, seeing the diseased and deformed working class toiling away at machines.

Graham then finds himself embroiled in a counter-revolution, as the outraged workers rise up against the duplicitous Ostrog. The conflict ends in an aerial battle, allowing Graham to put his newfound piloting skills to the success. Ostrog’s forces are routed, although Graham sacrifices himself in the process.

“The Atomic Riddle” by Edward S. Sears

A bank in Houston, New Jersey, stores $100,000 worth of notes in a new safe – only for the money to disappear overnight. Suspicion falls upon Roger Bolton, the young cashier who handled the deposit and knows the safe’s combination; but he maintains his innocence, and his wealthy fiancée Olive Velie refuses to believe that he could have committed the crime.

A bank in Houston, New Jersey, stores $100,000 worth of notes in a new safe – only for the money to disappear overnight. Suspicion falls upon Roger Bolton, the young cashier who handled the deposit and knows the safe’s combination; but he maintains his innocence, and his wealthy fiancée Olive Velie refuses to believe that he could have committed the crime.

Seeking help in clearing the name of her beloved, Olive goes to visit one Dr. Milton Jarvis. The doctor agrees to lend his know-how to the case and teams up with a detective, Inspector Jarvis. Before long, both men find themselves targets of assassination attempts, courtesy of the true culprits.

To Craven’s bewilderment, Dr. Jarvis embroils him in an intricate scheme that involves visiting the scene of the crime with Roger Bolton, Olive Velie, a convicted safecracker named Frenchy who is currently on parole, and representatives of the communist state of Molgravia.

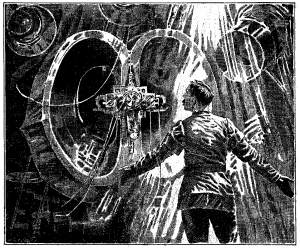

At this gathering, Dr. Jarvis delivers a lecture on chemistry before pointing out a piece of evidence that the detectives missed: two circular bands on the safe, one on the side and the other on the top, each a different colour from the rest of the metal. He explains that the robbers cut two circular holes into the safe using conventional blowtorches, and subsequently welded the removed portions back into place with a more specific implement:

“Now for a moment I must tax your patience with a description of the instrument used for this purpose. It is a welding torch with tungsten electrodes, arranged at an acute angle toward each other. Their distance apart is regulated by pressing a lever set in the handle of the torch. The alternating current from any socket would serve admirably for power. A tube passes through the handle and through this tube flows a stream of hydrogen. This stream of hydrogen passes through the electric arc, and is reduced to atoms. Passing through the arc, it is in the atomic state at the point of welding. Burning again to the molecular state, it generates a heat that will fuse anything. As the reducing action of this atomic hydrogen is so powerful, no carbon, oxygen or nitrogen contamination can occur. The weld can be made as clean and smooth as desired.”

The true culprit is exposed as Frenchy, who acted on behalf of the Molgravians. With his name cleared, Roger Bolton is free to marry Olive, and the two decide to name their future baby in honour of Dr. Jarvis.

“The Atomic Riddle” is one of Amazing‘s occasional forays into the mystery genre; this time the scientific element is not the means of catching the culprit, as in William B. MacHarg and Edwin Balmer’s Luther Trant stories, but rather the means of carrying out the murders. It is focused more on the technological means of the crime than on the motives of the villains, which turn out to be tied to the politics of a fictional country.

“The Golden Vapor” by E. H. Johnson

Set in Germany following the Great War, “The Golden Vapor” tells the story of Dr. Grieg, mixing his fictional biography with real-life events in scientific research – particularly the science of x-rays, namechecking the likes of William Henry and Lawrence Bragg along the way. Inspired by the work of such greats, Dr. Grieg decides to go further:

Set in Germany following the Great War, “The Golden Vapor” tells the story of Dr. Grieg, mixing his fictional biography with real-life events in scientific research – particularly the science of x-rays, namechecking the likes of William Henry and Lawrence Bragg along the way. Inspired by the work of such greats, Dr. Grieg decides to go further:

He must make atoms—atoms of helium, for instance, do some of the things that the alpha-particles of radium had been shown to do. Perhaps it might be possible to do even more.

As befits a story about the manipulation of matter on the atomic level, “The golden Vapor” concentrates on the tiny details of its narrative. It uses a slow, meditative prose style that captures small moments:

Hour after hour his little clock ticked away the seconds and the little motor that drove the air-pump purred on so contentedly that one would scarcely have dreamed that its song was one of ceaseless labor and faithfulness. Perhaps it knew the importance of its task, and who shall say that the little old clock did not philosophize deeply before ticking off another second, knowing that no power could bring it back.

Dr. Grieger’s experiments are initially successful.

The principal steps in the process were as follows: A bulb containing, say mercury vapor, was set in the path of a beam of ultra-violet light which in turn also passed to the Medior, though the latter was possibly some feet away, (Absorption of these radiations by the air and other media had been obviated by giving the waves themselves a suitable form.) The grid in the Medior was then heated by an auxiliary electric current from a small storage battery, and the entire bulb was oriented so that its concave mirror faced the beam of ultra-violet rays. Then the high-frequency, high-potential apparatus was started and as soon as the condensers were adjusted to the proper capacities, the tiny sphere at the focus of the mirrors of the Materialize—would begin to glow,— a bluish vapor would surround it and soon minute globules of metallic mercury would begin to roll down the sides of the bulb and could be drawn into a beaker below.

Finally, Grieger places some iron bars into his invention, and watches as they disappear – only to be replaced with bars of gold. Has he achieved the alchemists’ dream of transmutation?

Not exactly, as it turns out. The following day, newspapers report that a shipment of gold has reached San Francisco – but, upon being opened, was found to inexplicably consist of iron bars…

“The Puzzle Duel” by Miles J. Breuer

With “The Puzzle Duel”, Amazing Stories gives its readers another story of scientific crime. Chicago University student Peters witnesses his Hindu roommate, Raputra Avedian, get into a violent disagreement with an unpleasant German student named Schleicher; this ends with Schleicher challenging Raputra to a duel. As conventional duels are not the done thing in twentieth-century America, Peters suggests that the two settle matters through a battle of wits using scientific know-how.

With “The Puzzle Duel”, Amazing Stories gives its readers another story of scientific crime. Chicago University student Peters witnesses his Hindu roommate, Raputra Avedian, get into a violent disagreement with an unpleasant German student named Schleicher; this ends with Schleicher challenging Raputra to a duel. As conventional duels are not the done thing in twentieth-century America, Peters suggests that the two settle matters through a battle of wits using scientific know-how.

One night, Peters finds Raputra in the throes of death. He deduces that Schleicher won the scientific duel, and becomes racked with guilt as he had not considered that his suggestion would lead to the innocent party’s death: “Surely the justice that in the movies always overtakes the wicked, was lacking in the real world.”

And so, he sets about pinning the murder on Schleicher. He teams up with toxicologist Dr. LeCount to try and identify the poison that killed Raputra; but although the two establish a likely means of murder, they are unable to obtain evidence that would stand up in court. Then, one day, Schleiche is suddenly killed – by an electrified trap that Raputra had set up before his own death. “Appropriately, by the hand of a man several days in his grave, movie-justice had been done!”

Amazing had published a number of stories that exploited racial stereotypes, and so “The Puzzle Duel” stands out as a story that directly condemns racism: “During the years just preceding the World War,” runs the opening narration, “our supposedly homogeneous country contained numerous undercurrents of race-hatred.” That said, it arguably takes an easy way out by casting a German as the villain at a time when World War I would still have been fresh in the readers’ minds.

“The Terrors of the Upper Air” by Frank Orndorff

Dexter and Kidwell, a pair of aviators, rob a bank and escape in a plane – and then perform at a State Fair, cheered on by crowds unaware of their larceny. The two aviators attempt to break the world altitude record and succeed, only for a funnel of air to hurl them still further into the upper atmosphere. Using a wireless radio to communicate with people on the ground, they report on the bizarre sight below them: hundreds of floating islands made up of a spongy vegetable substances that stays airborne with the aid of tiny gas pockets.

Dexter and Kidwell, a pair of aviators, rob a bank and escape in a plane – and then perform at a State Fair, cheered on by crowds unaware of their larceny. The two aviators attempt to break the world altitude record and succeed, only for a funnel of air to hurl them still further into the upper atmosphere. Using a wireless radio to communicate with people on the ground, they report on the bizarre sight below them: hundreds of floating islands made up of a spongy vegetable substances that stays airborne with the aid of tiny gas pockets.

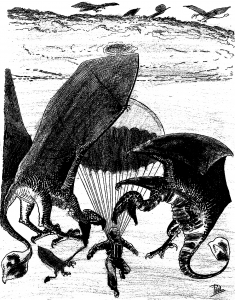

Animals exist in this sky-based ecosystem. One species initially seems to be a tiny bat, although closer inspection reveals it to be an unfamiliar variety of bird. Also present are creatures that resemble flying snakes, alligators and octopi.

The plane caught up in a scuffle between these fearsome beasts, and is so badly damaged that the pilots have to flee onto the islands of floating vegetation. Dexter’s final radio message to the crowd below is harrowing: he describes Kidwell trying to escape in a parachute and being torn apart by the monsters; Dexter then screams in agony as he too is killed by the megafauna of the skies.

Gruesome debris from the disaster falls to the ground before the shocked crowd – followed by notes from the bank heist. Pemberton, a detective investigating the robbery, is left pondering whether the aviators’ story is true or merely an elaborate ruse, allowing them to fake their deaths and escape with the remainder of the money.

A relic of an era before space travel, when writers were free to populate not only other planets but also the upper atmosphere of Earth with weird creatures, “The Terrors of the Upper Air” is similar to Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1913 story “The Horror of the Heights”. So similar, indeed, that author Frank Orndorff was likely drawing upon Doyle’s piece.

But notably, “The Terrors of the Upper Air” is louder and less subtle than its predecessor. Doyle’s slow, steady build-up is replaced with the excitement of an air show and a superfluous plot point involving a bank robbery. While Doyle populated the sky with ethereal beings that resemble vaporous jellyfish, Orndorff has his protagonists tangle with flesh-eating, dinosaur-like monsters. The story has also undergone a technological upgrade entirely in keeping with the Gernsbackian ethos: Doyle presented his tale as an excerpt from a journal, but Orndorff uses wireless radio as the pilots’ means of communication with terra firma.

Orndorff went on to pen the 1945 novel Kongo the Gorilla Man, but otherwise vanished from science fiction.

Read My Profile