CHAPTER 1

Each year when Shesheshen hibernated, she dreamed of her childhood nest.

Oh, the warmth of it. A warmth unlike anything in the adult world, soft and pliable heat keeping her and her siblings alive. In that warmth, they were fed raw life. Her father’s ribs, rich in marrow, cracking delicately in their mouths, and providing the first feast of their lives. His fat deposits were generous, and his entrails sheltered them from the cruel winter ele- ments. If Shesheshen could have spent her entire life inside the nest of his remains, she would have.

But all childhoods end. Hers ended when one of her sisters bit off Shesheshen’s left heel. Her siblings matured too quickly and hungered for more than their father. Shesheshen had to defend herself using jagged fragments of their father’s pelvis—his final and most gracious gift. The assault was a gift from her siblings, too, for she spent a week dining on their savory carcasses.

Mourning wasn’t natural to her. She missed the succulence of her sib- lings for some time, and had the errant moment of nostalgia for sharing their body heat. Little of her prey was memorable. Of her mother, she only remembered her wide maw and the artificial steel fangs she’d worn. Still, Shesheshen would always miss the nest that her father had made out of himself. He had been a good parent, and a better setting.

Nothing matched that nest. These ruins were little more than an un- loved cave. Where weather had caved in the ceiling, ornery spruce trees grew and plugged up the gaps. Poison ivy and spiderwebs were the few decorations, overgrowing everything architects had once achieved.

Deep beneath the ruins lay an underground hot spring that some aspiring human had connected to a bathing room. Nowadays the cham- ber was flooded with humid murk, gone brackish and amniotic from Shesheshen’s excretions. It was nearly opaque down in the waters. They were a refreshing place to hibernate through winter seasons.

Yet noises had roused her prematurely. Her lair had unwelcome visi- tors again. They did not even wipe their shoes.

She heard them before she saw them. The water of the hot spring stretched into so many cracks in the building’s foundations. Sounds from all ends of the property traveled through the network of water, alerting Shesheshen when something worse than a bear was coming.

“Good gods, above and below. Rourke? Do you smell that?” “Yeah. Like death without the sulfur. This is no wyrm.”

There were two visitors. Both human men, with two feet each, tram- pling over the weeds at her threshold. They paused in the foyer, snuffling and fighting with their gorges. Her foyer opened to many hallways, and one would lead them to Shesheshen. It was fortunate they didn’t know which one. She had to act before that changed.

The one called Rourke said, “Malik, don’t pass out on me. Put your mask on.”

“I’m fine,” the one called Malik said. “The contract is for a wyrm.

Could it be an eastern wyrm? From the Al-Jawi Empire?”

“Those smell like burned bread. This just stinks of infection. I’m tell- ing you, whatever is in this place isn’t a wyrm.”

The one called Malik spat upon the floor. He didn’t clean up after himself. “Then what is it?”

The one called Rourke muffled his coughing, probably behind a fist. “I’m not sure. But we need priests. At least three of them.”

Shesheshen liked priests. They tasted righteous. “Did I hear you two mention priests?”

Shesheshen had thought there were two. She was wrong—distracted and foggy-headed from having her hibernation interrupted. Whoever had yelled was a third voice, matched by the clank of heavy armor heading into her foyer.

She listened carefully around his footfalls; the noise of his gear was cacophonous, but she believed this third man was the last.The one called Malik said, “Sire Wulfyre, from certain environmental details we have reason to believe we need religious assistance—”

“For the last time,” the third man interrupted, “my family is not em- ploying the entire region. You said you were experts. Experts don’t need to hire bonus people. That’s the point of expertise. You want priests now? Do you two hunt monsters or just pray at them?”

The one called Rourke said, “Sire Wulfyre, you’re not going to want to come in here yet. The odor is overpowering.”

“Don’t tell me what to do. I’ve slain lords. The Wulfyres have killed off wyrms since—”

His words dissolved into wet choking sounds. The metal plates of his armor clicked musically, as though he was bending over. This third man was definitely retching. She hoped he had a helmet on so it painted the inside. It would serve him right for trespassing.

The name “Wulfyre” was familiar, too—a family who claimed some ownership over her lair and occasionally sent killers after her. She’d never actually met a Wulfyre before. She was in no mood to meet one now.

Rourke said, “We warned you about the odor.”

Sire Wulfyre said, “Next time come outside and warn me. Give me one of your breathing masks.”

Malik said, “This is sensitive equipment.”

Sire Wulfyre said, “Equipment my family is paying for. Now find this wyrm and kill it before I go looking for monster hunters who actu- ally hunt.”

Listening to all their words was exhausting. They were so noisy for professional killers. Any self-respecting hunters would’ve used the element of surprise. Why, if Shesheshen had been cold-blooded enough to kill peo- ple as a source of income, she would’ve slipped in here while she slept and poisoned the pool with rosemary and lye so she’d die in her sleep.

But Shesheshen was not a monster hunter. She was prey.

Three armed visitors, and she was still weak from hibernation. From the weakness in her flesh, she ought not have roused for weeks. Tensing her soft tissues made them tremble as though threatening to liquefy. She didn’t have the strength for a great battle today.

She had to do something, and soon. These murderers couldn’t be al- lowed to find her room and corner her. They’d do something awful like set the place on fire or collapse it atop her.

She opened pockets in her flesh and took in her first real breath of the season. The air was stale and frigid, making it feel as though icicles were forming along her innards. She shuddered, using the air to puff out her body, and emerged from her pool. Water streamed from the many lumps of her body, gone loose from weeks of slumber. The water sloshed across the stone floor, until she wholly emerged. All that submersion in water left her flesh sodden. She took a step, and collapsed against the nearest wall.

It was always tricky, getting the hang of being conscious again. Hope- fully the monster hunters hadn’t heard that. It would be embarrassing to die in this state.

Most bones that she kept inside herself during hibernation digested down to nothing.

Her kind did not naturally have many solid internal structures, just as the hermit crabs on the north beaches naturally lacked shells. They had to scavenge. Her mother had worn prosthetic steel fangs to compensate when she hunted. That one memory of her mother taught Shesheshen the importance of keeping tools around.

Along the floor of the bathing room lay iron rods and dense stones, which she’d left out last season. She rolled across them, letting them cut through external layers of her flesh with a sting that felt like waking up. Her innards squeezed those rods and stones, aligning them into a loose skeletal structure. A steel chain once used to bind her now made an excel- lent spinal column, flexible without breaking when catapults lobbed de- bris at her.

Inside her chest, where humans put their lungs, she placed an open bear trap. It was her prized skeletal possession. It did not trap bears any- more. Instead, she kept it as a secret pair of jaws, for when people needed to be bitten.

The harder ends of her makeshift bones tore apart her insides, and her poor tissues had to generate cartilage and tendons to adjust. It was an ache that left her shuddering against the wall. Was this how getting older felt? Wulfyre was louder now, audible through the limestone walls and down her hallway. He hollered, “I want the wyrm slain before Mother reaches the countryside. Do you know how upsetting it would be for her to en- counter that thing? Of course you can’t. Now you say you don’t even know what it is.”

Malik’s voice was softer. Shesheshen had to strain to hear him. “The creature has left many markings in the stone that could be claws or teeth, and we haven’t found any droppings yet. We’re still investigating.”

“Father died fighting this thing, so I can promise you my family knows what it is. It’s a wyrm.”

That was a familiar word. Shesheshen had been called a wyrm many times, often by startled hunters. She’d also heard “wyrm” used to describe drakes, harpies, qilins, kappas, and giraffes. In her experience, it was an epithet for whatever thing greedy humans wanted dead and were too afraid to kill themselves.

“Wyrm or not,” Rourke said, “if you really want this thing dead, there is only one way to go about it. To purge it and harm it enough to slay it, you’re going to need to burn this lair to the ground.”

“Oh, yes. I’ll just burn a stone building. Thank goodness I hired pro- fessional advice.”

“It could be tucked anywhere in here. With enough oil, fire will find it.” “This place is my family’s ancestral home. Of course you don’t care about the priceless heirlooms being destroyed. But I hired you to bring me the wyrm’s blood. One of you two can read, can’t you? It’s in your contract. Mother wants its heart. We can’t exactly bring her a heart that’s burned up.”

Malik said, “Perhaps we should talk strategy in private.”

The Wulfyre kept ranting. “No strategies that include broiling it. If you want to get paid, you’re slitting it open over a vase. Mother was very clear: blood, not fire.”

Well, this was interesting. The Wulfyre family was going to be disap- pointed when they learned she didn’t have blood. She didn’t have one of those pesky mammalian circulatory systems at all.

Rourke said, “You’re not paying us enough to die in here.”

“Go on, then. Breach the contract. Then you’ll be outlaws. Let’s see how much business you get with Mother and L’État Bon hunting you.”

Malik whispered like a man who didn’t know how to whisper. “Rourke.

Come on. We have rosemary oil. Locals swear it works.”

Then there was the rustle of leather being pulled off of blades. Rourke said, “How much rosemary do we have?”

That made Shesheshen grip the limestone bricks of her wall. These peo- ple had rosemary oil?

She cursed out of multiple orifices. These monster hunters had done their research. One of the things she couldn’t tolerate was rosemary. Once a local girl had candied it and fooled her into eating it, and Shesheshen pissed bile for a week.

As it was, her flesh struggled to keep her aloft on her makeshift bones. She needed to eat and gather strength. A fight would not go pleasantly. The last thing she wanted to wake up to was dying.

Getting older had given her wiles. While the humans chatted about how best to kill her, she went through some growing pains and formed two relatively passable legs. She hobbled for a while, convincing herself that these knees and ankles mostly worked.

On a rack beside the door was a set of wigs she’d made from the scalps that people hadn’t been using anymore. She selected a wig of sooty black hair for her disguise. Then she added a red riding hood; it was a leftover possession of a bygone occupant of the lair, from back when this building had been a castle or brothel or whatever humans enjoyed.

As her innards churned to form an esophageal passage, she wrapped the red garment around herself, pulling the hood low to hide how little of a face she had. It was an old role. By shifting her body mass within the cloak, she gave the illusion of a lithe frame. The belled-out bottom of the cloak gave her plenty of room to hide most of her body mass. She had passed as a human on plenty of excursions when she was at full strength. Doing so depleted from hibernation was a gamble.

Shesheshen pushed downward on the door as she opened it, so that the wooden door scraped along the stone landing. The sound stung her ears, and if it bothered her, it was likely to make these men soil them- selves. Part of the plot was announcing herself in advance.

She ran with wet feet slapping the floor, loud as she could be. They would know something was headed in their direction, and they would be ready for a nightmare.

What they got was a girl’s harried face poking out from under a red riding hood, gloved hands flailing. She turned as frightened a face as she could on them—it was easy to make, since they made three frightened faces at her.

All three of the murderers she’d eavesdropped upon stood in her foyer. Two of them wore practical leather gear and chain mail, with awkward half-masks over their mouths and noses. One man was much younger, shaped like a barrel that had grown arms, with several jeweled piercings in his ears. The other was a withered old root of a man with tufts of gray hair sticking out of every spot on his uniform, and eyes the green of pine needles.

These two must have been Malik and Rourke, standing in front, each holding polearms with their blades pointed down the hall at her. They protected the third man.

The third man hid behind them, wearing golden plate armor all the way up to his throat. Who wore gold for defense? It wasn’t holy, it was terribly heavy, and it was one of the softest metals Shesheshen had ever bitten. His chestplate was molded to have the likeness of nipples and rip- pling abdominal muscles. Parts of her salivated at the thought of crushing that chestplate. At his hip, he held some kind of crossbow at a bad angle, more likely to hit one of his underlings than her.

Well, it was easy to pick out which one was Wulfyre.

Shesheshen said, “Sires and masters. Thank the good gods, above and below, that you came. The wyrm could wake at any moment. Please, keep your voices quiet or we’ll all be skinned alive.”

She kept her own voice soft, since a whisper was easier to fake than a full-throated human voice. It took quite some concentration to keep a vocal passage open and functional like this. It would be easier once she consumed one from a person. Perhaps one of the hunters would donate.

The older hunter, Rourke, lowered his polearm. “What are you doing here, lass? The townsfolk said no one has approached this lair in years.”

“Sire,” Shesheshen said. “The wyrm has kept me in darkness so long that I have no memory of when it kidnapped me. It held me in one of the lower chambers of this place.”

The younger hunter, Malik, made a holy sign in front of himself, then asked, “It held you?”

Rourke said, “I thought anyone abducted by this thing would’ve been consumed before it went to hibernate.”

Well, the old hunter was right about that. Shesheshen never left food in the cupboard before hibernation. If you did, the remains spoiled and attracted scavengers. Scavengers were a nuisance when you were trying to regenerate.

She mimicked Malik’s holy sign with one hand, then resumed clutch- ing her cloak. For some reason, clutching at clothing was a classic human sign of being pathetic. In her experience, clothing never ran away from you even when a monster literally ate your head.

“Sires, the wyrm spares my life for my songs. It can only slumber when I sing to it the dark songs of distant lands. I know not where these verses come from, and they chill me to my core. Yet if it wakes, it will destroy the village with its ravenous appetite.”

“Your squeaky voice?” said the man in gold, definitely Wulfyre. “I guess a hellbound monster would have shitty taste in music.”

Both monster hunters shot glares at their employer. Yet those glares were gone before Wulfyre saw them. Hedged sincerity. A classic hu- man trait.

Malik asked, “What is your name, madame?” Shesheshen pondered. “Roislin.”

It was a plausible Engmarese name. Someone she’d eaten had probably had it.

Rourke said, “Roislin. My name is Eoghan Rourke, and this is my part- ner, Nasser Akkad Malik. Our employer here is Catharsis Wulfyre, son of the Baroness. We have seen so much pain that monsters have created in this world. Nobody should be left alone with a beast so unholy and wretched. Come with us. We’ve got water and honeycomb in our wagon. Right, Malik?”

“That’s right,” Malik said, holding out a hand for her. “We’ll get you out of here. You’ll be in town by tomorrow.”

Town was the last place she wanted to go. It was full of wretched hu- mans, precisely the kind that hired monster hunters in the first place. What she needed was rest and isolation.

Adding more squeak to her voice, she said, “Sires, if we flee together, then the wyrm will be on us before we reach the second hill. She knows my scent above all at this point. Instead, I need you to retrieve me a weapon.”

Wulfyre was the one to say, “A weapon?”

“Please. On the northernmost island of Engmar, in the west, there grows a flowering plant that the locals call summoner’s jaw. It is the only herb the beast fears. It can rend her skin and make her husk wither. A curse from the good gods, above and below. If you can collect it, I can keep her slumbering until you return, and we can be free.”

Actually, she was not even mildly allergic to summoner’s jaw. Mer- chants called it a remedy for minor cuts and bruises. However, Engmar was multiple nations away. By the time these would-be murderers fin- ished their trip, she would be fully rested, fed, and ready to deal with them. If she got lucky, they’d spread the rumor of her one weakness so that later hunters would make the same mistake.

Malik said, “I’ve heard of summoner’s jaw. It’s used for medicinal pur- poses. Stands to reason that devils would be weak to medicine.”

Rourke lowered his mask, then unstrapped his bowl helmet and held it over his chest. “Roislin, I am also from Engmar. I have traveled the world many years, and seen many cultures. To stay in this cave, singing a mon- ster to sleep, in the hopes we will find its bane? You are the bravest hero I have ever encountered.”

“Fuck off.” Catharsis Wulfyre barged between the two monster hunters, causing Rourke to drop his helmet. It clanged off the floor, and Wulfyre kicked it so that it skidded out through the entrance of the lair. “I’m not riding around the countryside until my ball hairs turn gray looking for magic weeds. Mother is paying you to kill the thing this week. It cannot be alive when she arrives.”

Malik said, “Sire, this herb is the key to slaying your monster.”

“You don’t hire locksmiths to find a key. You hire them to pick open the lock,” Wulfyre said, spinning the cap off a jug as he went. He doused his breastplate and gauntlets in a viscous fluid. It puddled beneath him, on the floor at the end of the hallway. “Tie this girl up. Let’s go.”

Rourke paused in the pursuit of his helmet. “Tie her up? She’s an in- nocent.”

“She’s one of those virgins that wyrms love eating so much. On top of that, we know the monster likes her voice. It’ll crawl out of its shithole if we have the right bait. That bait isn’t a plant. Bait needs to squirm.”

Wulfyre bustled along the hall, coming straight for Shesheshen. The oil from the jug dulled the shine of his armor. Malik raced after him, grab- bing the man’s gold-plated bicep. Malik said, “Wait, wait. There has to be another way.”

From the exit, Rourke said, “We’re in over our heads here. Unidentifi- able monster. Unfamiliar ground. We need whatever advantages we can get to kill it.”

Malik said, “Like the summoner’s jaw.”

Wulfyre held up his gauntleted fingers, oil dripping between them. “We don’t need summoner’s jaw when we already know rosemary works on the thing. It’s not going to eat me with this much of the stuff.”

This had to slow down. Shesheshen tried to shrink into the adjacent hallway, while pushing a few of the sharper stones inside her body toward the surface, readying claws. “Sires, your voices. If you rouse the monster, no one will be safe.”

Wulfyre batted Malik’s hand away. “My family has slain wyrms this way for generations. Leave a useless commoner out where the monster can smell them, and when the monster comes out for a snack, we get the drop on it. Slit this thing’s belly, get the blood, and you two can spend the rest of your lives trying to spend all the money you just made.”

Malik’s feet slowed. He wasn’t chasing his employer anymore. “No.”

Wulfyre said, “My family is paying. I’m giving the orders, or you’re becoming wanted men. Which would you prefer?”

How Shesheshen wanted one of the hunters to stop this. For one of them to stand up for common sense, if not for the rights of a young dam- sel. A damsel who had offered them a perfectly good reason to get lost for a few weeks.

But humans never stood up for the right thing. They stood around feeling uncomfortable, and later pretended that feeling uncomfortable meant they were virtuous. Now Malik stood to one side, only slightly ob- structing Wulfyre’s path. Surely he’d feel awful about this tomorrow when he was spending his blood money, before running off with his partner to the next kill.

And they called her monstrous.

There was a way to salvage this without fighting them and getting killed. She started, “Sires, perhaps there is summoner’s jaw in Underlook Forest, to the south of here. It is where Papa and I first made sight of the monster, and Papa said he thought he saw its peculiar color in the brush. It could be why the monster so seldom hunts there. Less than a day’s travel. You could—”

Catharsis Wulfyre’s hand felt like winter had abruptly returned and fallen exclusively over Shesheshen’s face. His gauntlet dug into her flesh, squeezing her mouth closed.

He said, “That’ll shut her up. Get some chains.”

Worse than the metal or his strength was the chilling burn. While Shesheshen had no sense of smell, her flesh tasted the rosemary, making her hide bubble up, boils rising everywhere the oil made contact. Her eyes fled deep inside her head to protect from that hideous pain. It was so aw- ful that the urge to vomit overcame her.

She opened up her throat and chest cavity, and vomited the wide-open bear trap at him. It clanged shut, the noise echoing throughout the hall- way, cutting off Wulfyre’s shriek—as well as his right hand. Her bear trap had been too enthusiastic, biting straight through gold and bone alike, severing his hand between its jaws.

Wulfyre clutched at his mangled forearm. “Fuck! Fucking gods, help me!”

Shesheshen spat the trap and hand away, not wanting another taste of rosemary. Every spot where the rosemary oil had scalded her continued to crack and corrupt. She had to tear the skin off her own face and neck, screeching as she forcibly shed onto the floor. Stray juices poured from the wounds. Pain made her lose coherence, so that the bone-rods in her body jutted out and punctured her hide, knocking bricks from the walls in her flailing. She hoped she beheaded one of these damned self-important mammals.

By the time she could see clearly again, Rourke was gone. He’d fled as fast as a ghost that smelled reason in the air. Malik remained, bobbing around Wulfyre, trying to wrap cloth around the stump of the man’s arm as he guided his employer to the exit. It was a gusher of a wound, painting the floor with rich crimson.

Catharsis Wulfyre kicked one boot between Malik’s legs, snagged a knee, and tripped him to the floor. Malik went straight down, his skull making a heavy report against the stone floor.

Wulfyre stepped over his fallen henchman and kept going for the sun- light of the exit. He kept his mauled arm elevated, left hand trying to squeeze metal plates and apply some pressure. Gore still streamed out, painting his expensive armor with his own insides.

“Mother will come for you, you fish-drowner! You’re going to be a trophy!”

In the middle of his cursing, he stepped on a puddle of rosemary he’d left on the floor when he’d decided to baste himself. One heavy boot landed with a mild splish sound. Before he could raise the other leg in stride, he slipped. All several hundred pounds of man and gear veered across the corner of the hall, and he went straight down on his back.

Then there were two unwanted people on Shesheshen’s floor.

She let strands of her flesh dangle free of the cloak, the ends dragging on the floor until they found stones. She braced herself with the rods in- side them. The stones served as decent feet, but could be repurposed into flails. Her bulk swelled with each step, lumbering over the two intruders.

She was fantasizing about cracking Wulfyre’s armor like the shell of a lobster when he reached down with his remaining hand. Before she could leap on him, there was the thunking sound of his crossbow.

The bolt hit her high in the chest, near where the bear trap had been lodged. Now that was all raw tissue, so soft that the bolt pierced deeply through her innards. Its tip pricked the hide of her back.

Wulfyre said, “Right in your heart.”

Much as she didn’t have blood, she did not have a heart. She looked forward to ingesting this man’s soon enough. She grabbed the end of the crossbow bolt, which was unusually thick. A jerk did nothing to free it, and gave her seven smaller stings, where hooks from the bolt must have lodged inside her. She commanded her inner tissues to relax and release it. Instead, they went feverishly rigid. Her meat seized up and refused to obey her.

It was going to be a nuisance digging that thing out of herself. She needed to get her strength up. Fortunately, she had these two humans over for breakfast.

“Not today!”

It was the rusty voice of the elder monster hunter, Rourke. The old man ran into the hall with a torch burning orange in the air. He waved it wildly as he came at her.

“About time,” said Wulfyre, trying and failing to roll to his knees. That armor looked disgustingly heavy. He raised his arms at Rourke. “Get me out of here.”

Rourke ran to Wulfyre—then past him, and to Malik. He caught the younger man under the armpits, holding the torch in front of both of their bodies as he lugged him to the exit. They were both lucky that she was still getting her footing and fighting this contraption lodged in her chest. They would escape.

While Catharsis Wulfyre bellowed about broken contracts and what he’d do to their testicles, Shesheshen straightened up. If those monster hunters returned with proper weaponry, she needed to be ready. She formed two thick tentacles and wrapped them around the base of the crossbow bolt. Jerking it made her knees weaken, and half her frame quiv- ered from the pain. It hurt like a week of starvation jammed into one in- stant. What had they poisoned her with?

Wulfyre tried to sit up, and his ornate breastplate stopped him. That was what he got for wearing golden armor in the likeness of abdominals. Still he sneered up at her. He turned those strong cheekbones and his blond stubble up at her and said, “At least you’re dying with me. The Wulfyres never forget.”

Those were not the words of a worthy father. They were the words of breakfast.

***

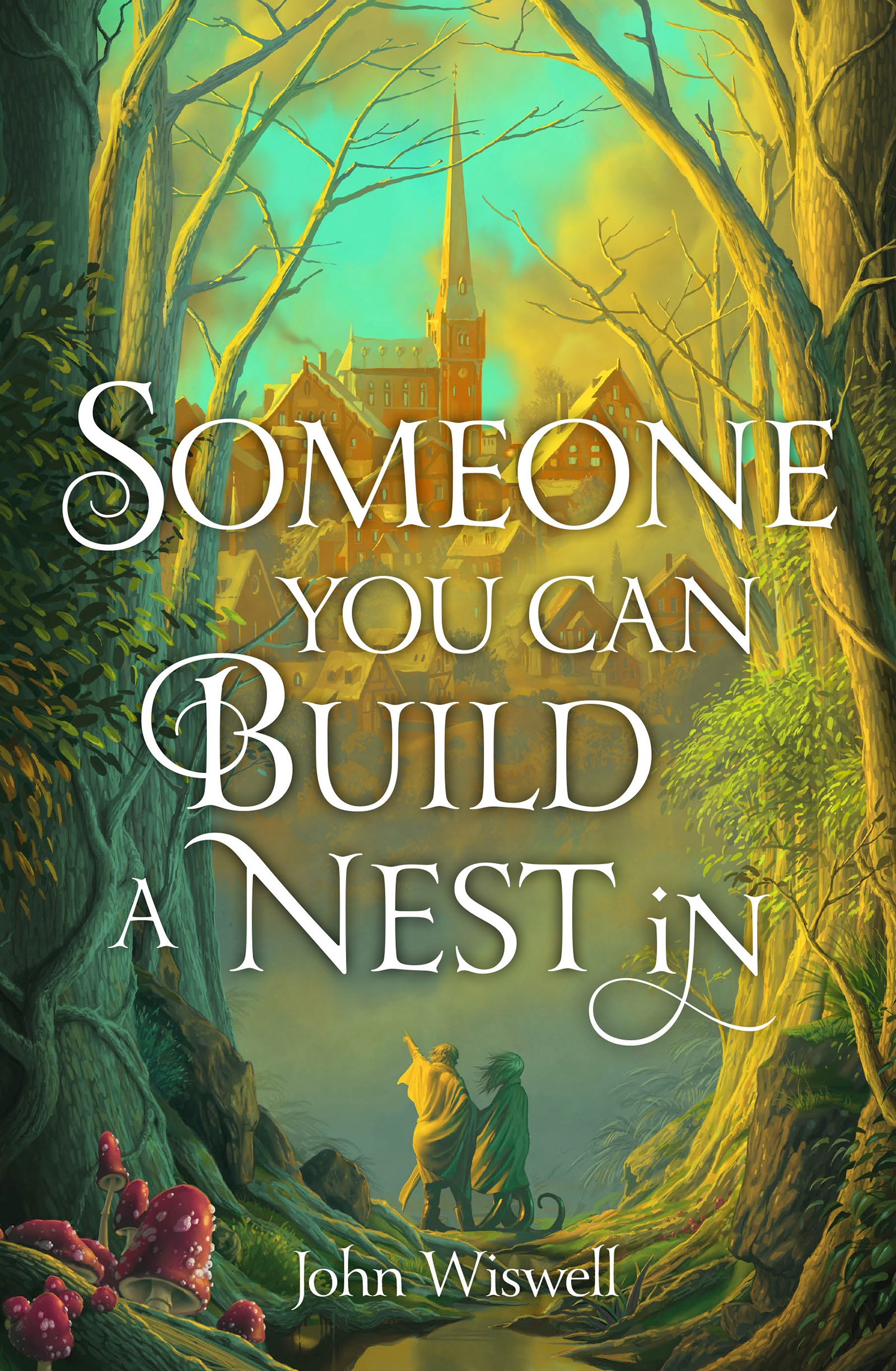

John Wiswell is a disabled writer who lives where New York keeps all its trees.

John Wiswell is a disabled writer who lives where New York keeps all its trees.

He won the 2021 Nebula Award for Short Fiction for his story, “Open House on Haunted Hill,” and the 2022 Locus Award for Best Novelette for “That Story Isn’t The Story.”

He has also been a finalist for the Hugo Award, British Fantasy Award, and World Fantasy Award. His stories have appeared in Uncanny Magazine, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Diabolical Plots, Nature Futures, and other fine venues.

His debut novel, SOMEONE YOU CAN BUILD A NEST IN, will be published by DAW Books in Spring 2024. He can be found making too many puns and discussing craft on his Substack, johnwiswell.substack.com.

Steve Davidson is the publisher of Amazing Stories.

Steve has been a passionate fan of science fiction since the mid-60s, before he even knew what it was called.