Life is in the business of geographical expansion. Spores ride the wind, seeds surf the waves, uncountable numbers are on the move this very moment on wing and paw. While moving from one place to the next might be a fundamental marker of life as we know it, the hills and moats we look to vanquish are no longer restricted to those on Earth. Billions of years of evolution have produced a species capable of unshackling life from Earth’s gravity well. Human ships have landed on other planets and the lunar regolith has borne our footprints. Given technological and manufacturing advances like the reusable rocket, it appears increasingly likely that we will one day inhabit other worlds, and with us, will come other life.

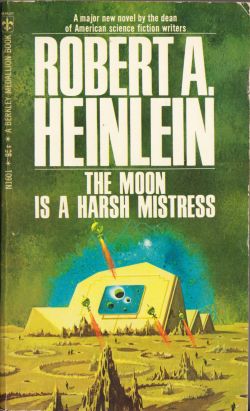

When we get there, what kind of societies will we build? What system of laws will govern us? Science fiction offers possibilities. Consider the 1967 Hugo award winning novel The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, by Robert A. Heinlein, that posited a lunar penal colony peopled by millions of criminals, political exiles, and their free-born progeny. The colony’s societal architecture is anarchist and libertarian, its infrastructure is maintained by a possibly sentient AI, and a trade federation oversees its wheat exports to Earth. The Expanse series by the writing duo James S.A. Corey describes a solar system rife with conflict. Corey is less interested in describing underlying societal governing structures, but in telling a story about how the solar system’s great powers use diplomacy, trade, and war to achieve political dominance, even as they face a mysterious alien threat.

When we get there, what kind of societies will we build? What system of laws will govern us? Science fiction offers possibilities. Consider the 1967 Hugo award winning novel The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, by Robert A. Heinlein, that posited a lunar penal colony peopled by millions of criminals, political exiles, and their free-born progeny. The colony’s societal architecture is anarchist and libertarian, its infrastructure is maintained by a possibly sentient AI, and a trade federation oversees its wheat exports to Earth. The Expanse series by the writing duo James S.A. Corey describes a solar system rife with conflict. Corey is less interested in describing underlying societal governing structures, but in telling a story about how the solar system’s great powers use diplomacy, trade, and war to achieve political dominance, even as they face a mysterious alien threat.

In the real world, international space treaties offer rules for space, where the Kármán line, roughly 100km above the Earth’s surface, is used as the differentiator between “space” and the sovereign-controlled airspace below. The Kármán line is more or less arbitrary, the Earth’s thermosphere and exosphere continue on thousands of miles farther. As Allen Steele’s zero-gee construction workers or “beamjacks” in The Near Space series discover, the space platforms and satellites they live on are subject to atmospheric drag and orbital decay even in what is considered “space”. Still, the line had to be drawn somewhere, and practicality is at the core of why most treaties exist.

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty covers practical matters like contractual damage liability, while also delineating international cooperation around issues like the rescue of stranded astronauts and limiting the use of weapons in space. The treaty was ratified by 114 countries, including all the major space-faring powers of the time. It does not address many topical items. For example, if a sovereign state or private entity builds a mining base on an extra-terrestrial body, does the land belong to them in perpetuity? Will ownership be limited to just the land on which the structures stand, or will there be a surrounding strip that will fall under the builder’s jurisdiction, like the 20km or so of territorial waters that line coastlines on Earth? Will we end up with tiny islands of vastly different jurisdictions separated from each other by narrow strips of no-man’s land?

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty covers practical matters like contractual damage liability, while also delineating international cooperation around issues like the rescue of stranded astronauts and limiting the use of weapons in space. The treaty was ratified by 114 countries, including all the major space-faring powers of the time. It does not address many topical items. For example, if a sovereign state or private entity builds a mining base on an extra-terrestrial body, does the land belong to them in perpetuity? Will ownership be limited to just the land on which the structures stand, or will there be a surrounding strip that will fall under the builder’s jurisdiction, like the 20km or so of territorial waters that line coastlines on Earth? Will we end up with tiny islands of vastly different jurisdictions separated from each other by narrow strips of no-man’s land?

The Outer Space Treaty draws heavily from the laws that govern the use of our oceans, laws that evolved over millennia. Treaties deal with establishing rules of good conduct between parties, which is roughly what ethics, the branch of philosophy that deals with “shoulds” and “oughts” explores. Almost every religious tradition comes with ethics built in, and there is often commonality between the traditions. According to the 4th century Greek philosopher, Aristotle, laws against murder and theft, for example, are universal because they are based on nature and constitute “natural justice”. Aristotle differentiated between rules that would be universally recognized from those based on societal and cultural laws unique to particular societies. Maritime and sea laws, given they apply to ships sometimes thousands of miles away from the jurisdiction of sovereign authorities, began as practical matters, stipulating rules around contractual obligations between ship owners, the merchants who owned the cargo being transported, and the captain and crew, for example. While maritime trade clearly existed during Aristotle’s time, indeed, carbon dated objects discovered in archeological sites around the world indicate intercontinental trade was happening thousands of years prior to Aristotle, the laws under which the ships sailed are lost to posterity.

The earliest set of preserved maritime rules is in the Byzantine Lex Rhodia (600-800 C.E.), that governed trade on the Mediterranean Sea.i The imperial Romans who enforced the laws at the time were primarily interested in ensuring that the trade of goods was carried out in a manner that protected all involved. The Rhodia laid down contractual obligations including how to calculate ‘average’, where the cost due to wreckage, fire, theft etc. would be averaged out and borne by all investors.ii Punishments for theft could be severe. For example, if the captain absconded with cargo, the entire crew would be held liable, their properties were liable to be seized, their wives and children sold into slavery, and they themselves could be executed.iii In times of war, any enemy ship, including any civilian transport or cargo vessel, could be attacked at will.iv The Rhodia’s influence continued through medieval times, including on the French Rolls of Oléron, for example, that was itself later codified by the English as the Black Book of the Admiralty, and used for hundreds of years more, notably by 18th century pirates, as immortalized by Robert Louis Stevenson in his 1883 novel Treasure Island.v Other medieval works like the Kitab Akriyat al-Sufun that provided maritime law for the Islamic Mediterranean during the Byzantine eravi and the Scandinavian Laws of Wisby,vii also draw heavily from the Rhodia.

The earliest set of preserved maritime rules is in the Byzantine Lex Rhodia (600-800 C.E.), that governed trade on the Mediterranean Sea.i The imperial Romans who enforced the laws at the time were primarily interested in ensuring that the trade of goods was carried out in a manner that protected all involved. The Rhodia laid down contractual obligations including how to calculate ‘average’, where the cost due to wreckage, fire, theft etc. would be averaged out and borne by all investors.ii Punishments for theft could be severe. For example, if the captain absconded with cargo, the entire crew would be held liable, their properties were liable to be seized, their wives and children sold into slavery, and they themselves could be executed.iii In times of war, any enemy ship, including any civilian transport or cargo vessel, could be attacked at will.iv The Rhodia’s influence continued through medieval times, including on the French Rolls of Oléron, for example, that was itself later codified by the English as the Black Book of the Admiralty, and used for hundreds of years more, notably by 18th century pirates, as immortalized by Robert Louis Stevenson in his 1883 novel Treasure Island.v Other medieval works like the Kitab Akriyat al-Sufun that provided maritime law for the Islamic Mediterranean during the Byzantine eravi and the Scandinavian Laws of Wisby,vii also draw heavily from the Rhodia.

In 1609, the Dutch jurist, Hugo Grotius, wrote the monumentally influential Mare Liberum (The Freedom of the Seas). The Mare Liberum continues to influence current maritime law including the 1994 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) that is now ratified by over 150 countries and territories. In Mare Liberum, Grotius argued that the sea, like air, was a property that did not belong to any one nation, but was to be used for the benefit of all countries: “I shall base my argument on the following most specific and unimpeachable axiom of the Law of Nations, called a primary rule or first principle, the spirit of which is self-evident and immutable, to wit: Every nation is free to travel to every other nation, and to trade with it.”

While Mare Liberum was a full-throated defense of free trade between nations, it was particularly focused against the Portuguese claim that Portugal had the sole right to trade with India.viii Grotius, writing on behalf of the Dutch East India Company, argued that although Portugal was indeed the first European country to reach India, they had not taken the lands by conquest or purchase, and therefore had no more right to control the sea-routes to India than had the Islamic countries or the Chinese who had already established trade routes there.

The positions espoused by Mare Liberum were favored by various countries at various times. When a European-wide treaty based on Mare Liberum was proposed in the mid-1800s, for example, it was the British who stood most against it.ix Why, asked the British, should the “Lord of the Seas” not use her hard-won naval superiority to the advantage of her people? Why squander it away by signing a treaty with weaker rivals? In particular, why allow “neutral” trading ships to pass unmolested on the high seas, especially during wartime, given that even non-military supplies would aid the enemy? These concerns are the kind that limit the effectiveness of any treaty. When any party believes that they are being singularly or selectively targeted, then that party is unlikely to comply. For example, several countries have conducted successful earth to space missile tests by blowing up one of their own satellites, even though these kinds of tests fall under a grey area of the Outer Space Treaty. Whether it is the United States led Artemis Accords or the Chinese-Russian spearheaded International Lunar Research Station, the treaties are more likely to be viewed as guidelines rather than anything that would supersede sovereign interests.

These are the best of times, at least for space. Multiple nations have already launched ambitious space programs. Scores of other countries wait in the wings. Space is no longer just for nation states either. Space is already a profitable endeavor, open to anyone with an appetite for risk. Private companies have galvanized the sector, already earning revenues in the hundreds of billions of dollars. With continued technological advances and manufacturing efficiencies, revenue is projected to reach a trillion dollars by 2040.x Just as the East India Trading Company competed head to head with the most powerful sovereign states of the time, today’s private entities stand similarly poised to influence space law. The arguments that Grotius’s Mare Liberum advances may yet apply if we encounter other intelligent civilizations in our explorations, as Murray Leinster predicted in his 1959 first-contact story, The Aliens.

These are the best of times, at least for space. Multiple nations have already launched ambitious space programs. Scores of other countries wait in the wings. Space is no longer just for nation states either. Space is already a profitable endeavor, open to anyone with an appetite for risk. Private companies have galvanized the sector, already earning revenues in the hundreds of billions of dollars. With continued technological advances and manufacturing efficiencies, revenue is projected to reach a trillion dollars by 2040.x Just as the East India Trading Company competed head to head with the most powerful sovereign states of the time, today’s private entities stand similarly poised to influence space law. The arguments that Grotius’s Mare Liberum advances may yet apply if we encounter other intelligent civilizations in our explorations, as Murray Leinster predicted in his 1959 first-contact story, The Aliens.

Aristotle’s universal justice will likely still hold, but laws peculiar to living in space will surely be enacted. Given religious traditions have always been a part of human civilization, it is likely that some jurisdictions will continue to thrive under religious principles. Others will follow secular traditions. While entirely new political philosophies are unlikely to emerge in the near term, newish ideas will likely be tried out. If sea law is any guide, life’s continued expansion away from the planet of our birth will succeed, but not without a few bumps.

i https://archive.org/details/nomosrhodinnauti00rhoduoft/page/n55/

ii https://archive.org/details/nomosrhodinnauti00rhoduoft/page/n256/