To answer my own headline, yes, there is too much to read, at least if you want to stay knowledgeably informed on the field. But there is a way to relatively quickly fill in the background, should you so choose.

I was very lucky in choosing my time and place for growing up: the Science Fiction genre was experiencing a growth spurt just prior to and during that event, with the result that much of the SF from before my time was being resurrected and showcased through anthologies and reprint magazines – mostly, I suspect, for two reasons. The first was, of course, crass commercialism: reprinting older works is less expensive than publishing the new. But that’s an old story. The other, probably more pertinent reason is – the need for content. Back in the late 60s and early 70s, the SF field did not have dedicated SF imprints at the major publishers. The number of original SF works published every year represents a mere handful of what it is today.

But what those circumstances led to was a whole generation of SF readers who had, for a brief time frame, relatively easy access to just about everything that had been published in the field to date, and the volume was not so great that a dedicated reader could truly have a handle on much of what the field produced at any given time.

This of course had wide-ranging ramifications, not the least of which on Awards such as the Hugo. There’s a reason why the suggestion that voters familiarize themselves with all of the nominated works in a given category is offered, and its historic: there was no real excuse back then for not doing so. Mt. TBR was not twelve miles high.

One could fairly easily polish off a month’s worth of magazines in a day or two of reading, leaving most of the rest of the week to absorb the few original paperback offerings that month and then fill in with older works. (At one time in my youth I was capable of reading 6 novels in a 24 hour period, and did so prior to an English Lit exam that I aced. I had to because I’d “wasted” most of my study time reading SF novels instead.)

Today, SF publishing has become a fire hose of content. That’s not inherently a bad thing, but it does make “keeping up” a near impossibility, even if one could read six novels a day on a sustained basis, which I assure you, I can not.

On the other hand, I do firmly believe that a background in the developmental history of our genre is essential for at least two groups of readers: academics who study the field and authors who really want to be able to write interesting, compelling, cutting-edge Science Fiction.

Why the latter? Two reasons: Because no matter how much we talk about and emphasize the importance of story and character, Science Fiction is still the “literature of ideas” at heart and if you aren’t aware of the ideas that have historically been presented in the literature, you are bound to recreate some of them, and most likely not as well presented as the originators. Which brings up the second reason. A lot of our literature is of the “call and response” variety. Our authors do not exist in a vacuum (makes for very short writing sessions if they do). They read other authors and, in many cases, are inspired to write their own interpretations of various ideas as expansion, commentary or alternative. The literature, as a whole, is additive, with each generation supplying bits of an ever expanding foundation.

Fortunately, you can play catch-up with many of the formative works of this genre by delving in to some of the original anthologies that appeared in the late 40s to mid-1950s. Just a small handful of books can take you from almost the beginning of the genre through the years when it began to really establish itself.

This particular era is very important and influential, if for only one reason: this is the era in which most of science fiction’s seminal concepts were played with for the first time in a science fictional manner. While it is true that many of the literature’s truly basic concepts – life on other worlds, space travel, time travel, alien intelligences, extra-sensory capabilities and many more were first written about in earlier eras, they were generally not treated in an extrapolative manner. Rather than being a central focus of the story, they are stage settings and hooks. Wells’ Time Machine is a transport device, not a tool for examining causality and paradox. The Martians are metaphor, not an alien culture that is examined for similarities and differences. It is in this era of the genre that scientifically based concepts are examined through a scientifically based lens.

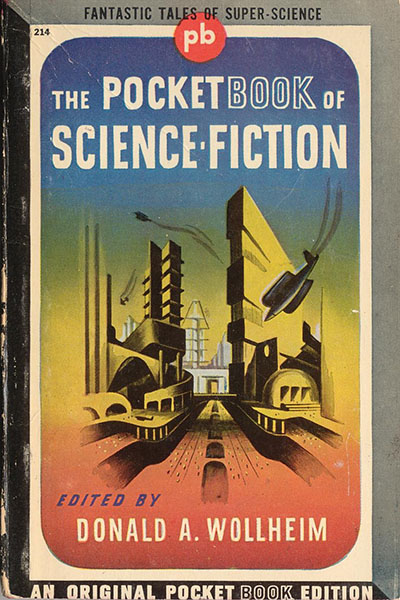

The first couple of anthologies comprising nothing but Science Fiction tales did not have much of an impact and do not really offer a survey-type look at the field, so we’ll leave those off the list (most of them are difficult and fairly expensive to attain as well), so we’ll start with Donald Wollheim’s Pocket Book of Science Fiction.

1943

1943

Introduction by Donald A. Wollheim

By the Waters of Babylon by Stephen Vincent Benét

Moxon’s Master by Ambrose Bierce

Green Thoughts by John Collier

In the Abyss by H. G. Wells

The Green Splotches by T. S. Stribling

The Last Man by Wallace West

A Martian Odyssey novelette by Stanley G. Weinbaum

Twilight by John W. Campbell, Jr.

Microcosmic God by Theodore Sturgeon

“—And He Built a Crooked House” by Robert A. Heinlein

This is a good mix of some early SF and works by notables in the field, many before they were notables. And they introduce some of the genre’s most basic themes: aliens who “think as good as a man, but not like a man (Martian Odyssey), greed vs scientific logic, accelerated evolution and many other themes such as humans accessing god-like powers (Microcosmic God): post apocalyptic cultures (By the Waters of Babylon). The anthology covers a wide range of what one might consider “introductory” SF topics, both in scope of time and subject.

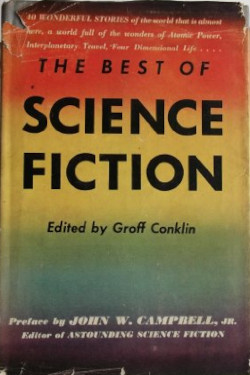

Next up: The Best of Science Fiction

Edited by Groff Conklin, who would go on to become a serial anthologizer, this one dates from 1946

Concerning Science Fiction by John W. Campbell, Jr.

Concerning Science Fiction by John W. Campbell, Jr.

Introduction (Best of Science Fiction)by Groff Conklin

Solution Unsatisfactoryby Robert A. Heinlein

The Great War Syndicate by Frank R. Stockton

The Piper’s Son by Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore

Deadlineby Cleve Cartmill

Lobby by Clifford D. Simak

Blowups Happen by Robert A. Heinlein

Atomic by John W. Campbell, Jr.

Killdozer! by Theodore Sturgeon

Davey Jones’ Ambassador by Raymond Z. Gallun

Giant in the Earth by Morrison Colladay

Goldfish Bowlby Robert A. Heinlein

The Ivy War by David H. Keller, M.D.

Liquid Life by Ralph Milne Farley

A Tale of the Ragged Mountainsby Edgar Allan Poe

The Great Keinplatz Experimentby Arthur Conan Doyle

The Remarkable Case of Davidson’s Eyes by H. G. Wells

The Tissue-Culture King by Julian Huxley

The Ultimate Catalystby John Taine

The Terrible Sense by Thomas Calvert McClary

A Scientist Divides by Donald Wandrei

Tricky Tonnage by Malcolm Jameson

The Lanson Screenby Arthur Leo Zagat

The Ultimate Metal by Nat Schachner

The Machine by John W. Campbell, Jr.

Short-Circuited Probability by Norman L. Knight

The Search by A. E. van Vogt

The Upper Level Road by F. Orlin Tremaine

The 32nd of Mayby Paul Ernst

The Monster from Nowhere by Nelson S. Bond

First Contact by Murray Leinster

Universe by Robert A. Heinlein

Blind Alley by Isaac Asimov

En Route to Plutoby Wallace West

The Retreat to Mars by Cecil B. White

The Man Who Saved the Earth by Austin Hall

Spawn of the Stars by Charles Willard Diffin

The Flame Midget by Frank Belknap Long

Expedition by Anthony Boucher

The Conquest of Gola by Leslie F. Stone

Jackdaw by Ross Rocklynne

Conklin has been one of my favorite anthologizers (Wollheim and Merrill figure in there as well) and this collection covers a lot of territory in both time and theme. It is helpfully divided into six parts, each collecting stories involving common themes – The Atom (atomic energy and its influences), The Wonders of Earth, kind of a catch-all for strange phenomena, The Superscience of Man – newly evolved super powers, Dangerous Inventions – the consequences of advancing technology, Adventures in Dimension – other realities intruding on our own and From Outer Space – which takes us to other worlds, alien beings and other cultures.

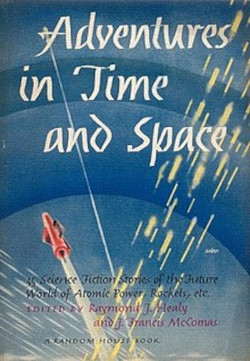

Next up is the great Healy & McComas’ collection, Adventures in Time and Space, also from 1946

Introduction (Adventures in Time and Space) by Raymond J. Healy and J. Francis McComas

Introduction (Adventures in Time and Space) by Raymond J. Healy and J. Francis McComas

Requiem by Robert A. Heinlein

Forgetfulness by John W. Campbell

Nerves by Lester del Rey

The Sands of Time by P. Schuyler Miller

The Proud Robot by Henry Kuttner

Black Destroyer by A. E. van Vogt

Symbiotica by Eric Frank Russell

Seeds of the Dusk by Raymond Z. Gallun

Heavy Planet Milton A. Rothman

Time Locker by Henry Kuttner

The Link by Cleve Cartmill

Mechanical Mice by Maurice G. Hugi and Eric Frank Russell

V-2—Rocket Cargo Ship by Willy Ley

Adam and No Eve by Alfred Bester

Nightfall by Isaac Asimov

A Matter of Size by Harry Bates

As Never Was by P. Schuyler Miller

Q. U. R. by Anthony Boucher

Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell, Jr.

The Roads Must Roll by Robert A. Heinlein

Asylum by A. E. van Vogt

Quietus by Ross Rocklynne

The Twonky by Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore

Time-Travel Happens! by A. M. Phillips

Robot’s Return by Robert Moore Williams

The Blue Giraffe by L. Sprague de Camp

Flight into Darkness by J. Francis McComas

The Weapons Shop by A. E. van Vogt

Farewell to the Master by Harry Bates

Within the Pyramid by R. DeWitt Miller

He Who Shrank by Henry Hasse

By His Bootstraps by Robert A. Heinlein

The Star Mouse by Fredric Brown

Correspondence Course by Raymond F. Jones

Brain by S. Fowler Wright

This one quickly became the go-to one volume exemplar of what the field was all about, though it does show a distinct preference for humorous science fiction, from The Star Mouse to The Proud Robot, to Symbiotica and The Twonky.

These three volumes alone will give you a good start, with stories published from 1896 (Wells) to 1946 (van Vogt) and a taste of a whole bunch of influential names, which I’ve picked out above in bold. Not to mention some very storied stories –

By the Waters of Babylon

A Martian Odyssey

Twilight

Microcosmic God

Blowups Happen

Killdozer!

First Contact

Nerves

The Proud Robot

Nightfall

The Weapons Shop

Farewell To the Master

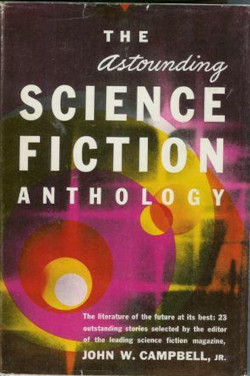

Then, you’ll want to pick up The Astounding Science Fiction Anthology, which will capture a good portion of the fiction from Astounding Stories/Astounding Science Fiction when it was at its most influential.

Introduction (The Astounding Science Fiction Anthology) by John W. Campbell, Jr.

Introduction (The Astounding Science Fiction Anthology) by John W. Campbell, Jr.

Blowups Happen by Robert A. Heinlein

Hindsight by Jack Williamson

Vault of the Beast by A. E. van Vogt

The Exalted by L. Sprague de Camp

Nightfall by Isaac Asimov

When the Bough Breaks by Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore

Clash by Night by Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore

Invariant by John R. Pierce

First Contact by Murray Leinster

Meihem in ce Klasrum by Dolton Edwards

Hobbyist by Eric Frank Russell

E for Effort by T. L. Sherred

Child’s Play by William Tenn

Thunder and Roses by Theodore Sturgeon

Late Night Final by Eric Frank Russell

Cold War by Kris Neville

Eternity Lost by Clifford D. Simak

The Witches of Karres by James H. Schmitz

Over the Top by Lester del Rey

Meteor by William T. Powers

Last Enemy by H. Beam Piper

Historical Note by Murray Leinster

Protected Species by H. B. Fyfe

This volume, drawn from the pages of Astounding magazine, is a pretty darned good survey of the “Golden Age” of science fiction, at least as envisioned and managed by Campbell. Despite his biases and kooky forays into pseudoscience, Campbell did establish the SF story as “thought-experiment”, a story deliberately examining a concept in the form of an at least semi-formal hypothesis. In other words, applying scientific methodology to the writing of speculative fiction.

Those four volumes, some 108 short stories, novellas and novelettes, is not an overwhelming volume of material, and there are surprisingly few overlaps.

After this “grounding” read, there are many other fine anthologies to choose from, but I will recommend the following course of action: first, read The Science Fiction Hall of Fame –

Introduction (The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume I) by Robert Silverberg

Introduction (The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume I) by Robert Silverberg

A Martian Odyssey by Stanley G. Weinbaum

Twilight by John W. Campbell, Jr.

Helen O’Loy Lester del Rey

The Roads Must Roll by Robert A. Heinlein

Microcosmic God by Theodore Sturgeon

Nightfall by Isaac Asimov

The Weapon Shop by A. E. van Vogt

Mimsy Were the Borogoves by Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore

Huddling Place by Clifford D. Simak

Arena by Fredric Brown

First Contact by Murray Leinster

That Only a Mother by Judith Merril

Scanners Live in Vain by Cordwainer Smith

Mars Is Heaven! by Ray Bradbury

The Little Black Bag by C. M. Kornbluth

Born of Man and Woman by Richard Matheson

Coming Attraction by Fritz Leiber

The Quest for Saint Aquin by Anthony Boucher

Surface Tension by James Blish

The Nine Billion Names of God by Arthur C. Clarke

It’s a Good Life by Jerome Bixby

The Cold Equations by Tom Godwin

Fondly Fahrenheit by Alfred Bester

The Country of the Kind by Damon Knight

Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes

A Rose for Ecclesiastes by Roger Zelazny

which has a fair amount of overlap with the preceding volumes (saving you even more time!) and also the virtue of having been selected by both Silverberg (no mean anthologizer himself!) and the members of the newly formed SFWA, while ranging from the 30’s to the mid-60s in time span. It also manages to shoe-horn in Judith Merrill, Richard Matheson and Cordwainer Smith, along with the “standards”, offering a wider range of writing styles than the previous volumes.

The addition of Hall of Fames takes us up to the mid-1960s. To continue on your journey, I recommend veering off this path a bit and delving into one or more of several annual anthology series.

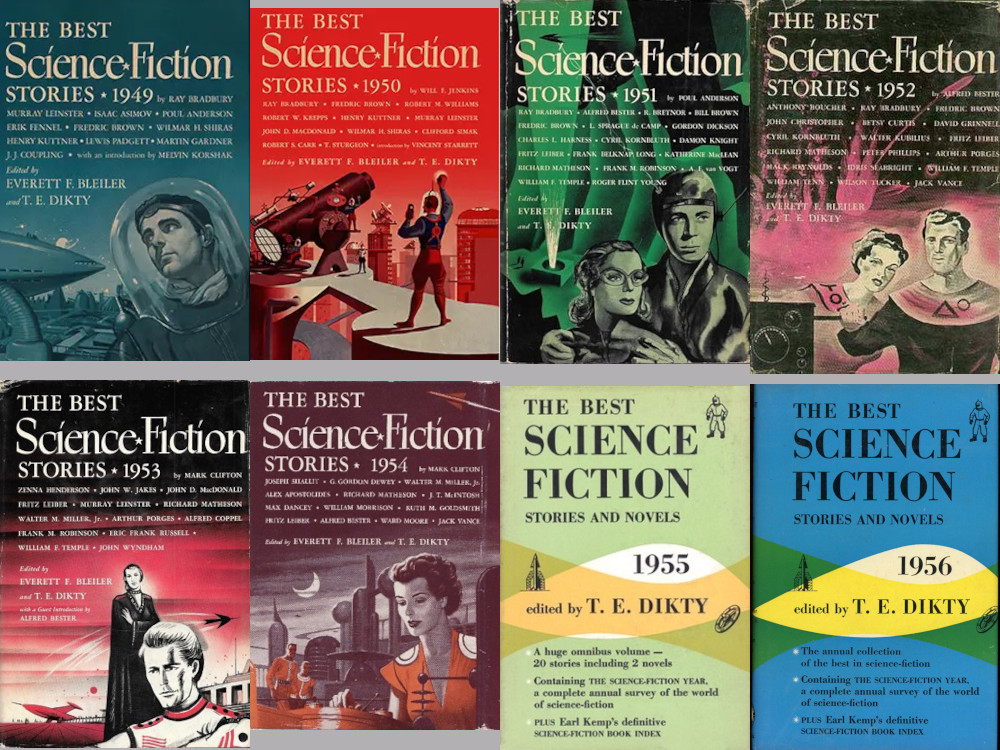

Each is a snapshot of a year’s creativity in the field. If you can find them, it might be interesting to begin with the very first annual anthologies The Best Science Fiction Stories (Year) – 49, 50, 51,52, 53, 54, 55, 56. T E Dikty compiled a bibliography early on and E F Bleiler used it to put together the first comprehensive bibliographic survey of the field. Together, the two went on to offer this series.

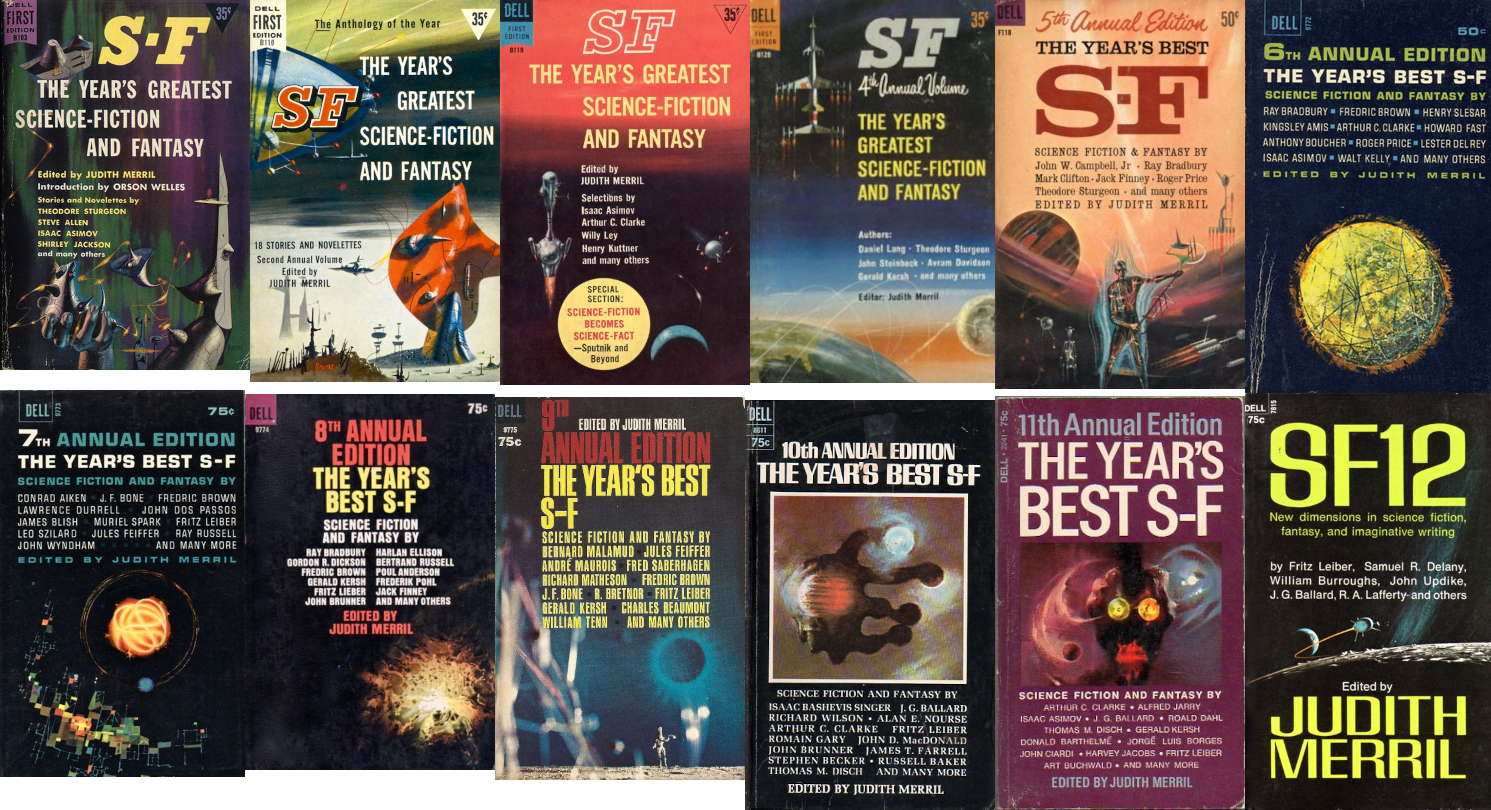

and/or Judith Merrill’s own annual series, which has perhaps some of the best interstitial material of any of these kinds of series, and ranges much farther than just the SF magazines to compile its material. Judith seemed to want to expand the range of the genre and included more literary-oriented works, taking a softer approach to the establishment of a “New Wave” than would be expressed a decade or so later. The series ran from 1956 through 1968.

There are many, many, many more anthologies from this twenty year era (1946 to roughly 1968, but the mantle of attempting to survey and represent the field is probably best represented, at least for another decade or so, by the joint effort of Donald Wollheim and Terry Carr with their World’s Best series that began in 1965, though these volumes took a more pedestrian approach than Merrill’s by including few, if any notes on the assemblage.

That series began in 1965 and would extend to 1990 with some title and editor changes along the way.

Now stop wasting time here and get cracking! There will be a test.

A final note: all of these anthologies are subject to the same limitations and then-contemporary issues many have criticized it for. You will find casually assumed misogyny, a distinct lack of electronic tools as we have come to know them, little consideration for racial issues and a distinctly Anglo-centric and American-centric (some might even be moved to say “colonialist”) approach, , but I urge you to remember that none of these stories was written in a vacuum (quite the sensation if any had been), and to remember that Clarke’s Dictum is generally presented in an incomplete manner. Sufficiently advanced technologies will be indistinguishable from magic – to insufficiently advanced individuals.

In other words, the possessors of advanced technology do not perceive it as magic and view those who do as ignorant savages. The authors of these now nearly ancient stories would perceive our current cultural constructs as “magic” if they were exposed to them during their own times.

Which is why I will urge you to seek out works like Women of Wonder (Lisa Yaszek) or Africa Risen (Thomas, Ekpeki) to begin to round out your SF reading activities.

Nice article. I’ve read a lot of these stories and owned or read many of these exact anthologies over the years. Some of them are still tucked away in bookshelves around the house. Some have travelled on to other places and hopefully other readers.