OBIR: Occasional Biased and Ignorant Reviews reflecting this reader’s opinion.

HOW TO WRITE A NOVEL

Premise:

That I know how to write a science fiction novel.

Article:

Darn silly idea. Me? A critic? What do critics know about writing novels?

“Almost nothing,” most authors would argue, basing their opinion on the reviews of their works that have come their way. They have a point.

Still, one reason my “weekly” CLUBHOUSE columns have been so erratic in their schedule of late is the fact that I have been working on a novel these past seven months. As of this moment my first draft is 65,000 words long. I figure it will be complete within two weeks.

The main point of this article is: if I can do it, you can do it.

And what science fiction reader hasn’t dreamed of becoming a writer? After all, you already know the sort of books you like to read; why not write one of your own?

I made that decision in 1967. I was 16 years old. I was lying in bed doing my Latin homework and wondering “What sort of career is this preparing me for?” I put my textbook down and pondered the question. A mental image flashed in my head, a vision of a shelf holding fifty paperback novels, all with lurid covers and my name on the spines.

Why not? What an easy way to make a living! Get up in the morning, prepare a cup of coffee, sit down at your desk in your pajamas, and type for a couple of hours. Then go back to bed. Finally, get up around Noon and enjoy the rest of the day doing whatever you feel like doing. Enough days like this and you have a manuscript to bang off in the mail to the publisher. Let him get to work selling your book and earning you a fortune, and all you have to do is start work on your next novel.

I already knew that publishers kept their stable of writers backlist forever in print, and that readers like me, on discovering a writer they like, immediately buy up everything they’ve written. Consequently, a novelist’s career is always a chart exhibiting exponential growth. The more you write, the more you earn. Every year more profitable than the last. What could be a better way to make a living?

I remember I was so excited I leaped out of bed to grab pen and paper to write down a list of sure-fire titles that were springing to mind. I still have that piece of paper. Titles like: AGAINST THE MALUII, IN THE NIGHT OF THE SKY, ONCE UPON A BRIGHT-LIT MOURNING, TORSEN IV TROUBLE SPOT, GARRISON PLANET, KEEPERS OF THE GAOL, VIPTRON LTD, PLANET REVOLUTIONARY, EMPIRE BARBARIANS, MARAUDERS OF THE DEEP, and so on. You get the idea.

The very next day I began work on “AGAINST THE MALUII” which I pronounced “Mal-You-Eye” but everyone else read as “Ma-Louie.” I even grabbed some crayons and sketched out a portrait of the alien villain I had in mind. In retrospect, it rather resembled the Gorn I’d seen in the Star Trek episode ARENA when it aired earlier in January that year. I no longer have it, but I recall paying particular attention to its powerful musculature. I also remember my aunt Vicki, on seeing the art (meant to be the frontispiece of my novel), asking “Why does it have such big tits?” I’d gone a bit overboard drawing the pectorals.

First lesson learned. People don’t always interpret your creative work the way you intended.

Over the next twenty years or so I wrote several novels and sent them off to unsuspecting publishers. Never made any sort of advance query. Just sent in the complete manuscript. By mail I hasten to add. No other way to do it back then.

One was a mainstream novel I called RAINSHINE It was about a teenager living in Vancouver suffering from extensive angst. Well, they say “write what you know” and that’s all I knew. I had high hopes. Teenage angst. What an original concept! Bound to sell.

I submitted it to Clarke, Irwin & Company Ltd (Toronto) in July of 1975. In April of 1976 editor Shelley Tanaka rejected it, writing “Your work was read several times by our readers and discussed at length with the editorial board. We felt that it showed a great deal of promise—that the portrayal of the protagonist was credible and sympathetic and the dialogue realistic. There is some fine imagery and perceptive inner monologue.

However, our readers commented that the novel lacked sufficient tightness and grip. Some of the philosophical discussions tended to be drawn out, repetitive, and occasionally lapsed into cliché.”

Being stubborn, I rewrote the novel and sent it back to them even though they hadn’t requested I do that. In June of 1977 they returned the revised manuscript, with Shelley commenting: “Our readers found the novel considerably improved—tighter and more powerful. The character of the protagonist comes through and the inner monologue is quite absorbing. We felt, however, that the novel may ultimately suffer by the purposefully single theme, limited number of characters, and constant inner monologue style; that the lack of variety in tone and plot may limit its popular appeal and marketability. Thus, although we believe that RAINSHINE is now more consistent, controlled and absorbing than it was in the original version, we are still not convinced that reader interest is sufficiently maintained.”

I quote the above as an example of vintage publisher-critiquing from the 1970s. I have no idea what sort of critiques modern publishers give today when rejecting a novel, or if they even have time to bother. At any rate, it was obvious then I had much to learn. So I entered the University of British Columbia, majoring in Creative Writing, and eventually graduated in 1981 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree.

A glutton for punishment, I showed RAINSHINE to Jake Zilber, one of my professors. Here is his response: “In RAINSHINE you show that you have the ability to look at and listen to the world outside yourself and to write about it in such a way as to make the reader see and hear people, places and things quite clearly. Also, in a section such as the one about the porno shop, you show a capacity for creative drama and tension and suspense. Then, too, the honesty of tone throughout the novella is very appealing. And the wry, bittersweet humor adds to the effect.

Having said that, it is the work of an apprentice. The protagonist spends a lot of time exploring his own thoughts; he is never seen in connection with his family or friends, and, in fact, doesn’t even think about them, despite the fact he is so introspective about his own problems… the protagonist is essentially passive and lets things happen to him, rather than pursuing a goal; the plot is subordinated to the introspection and is not exploited in order to create greater suspense; the protagonist is a young writer worried about whether he’s a writer; and the ending seems contrived.”

All of the above I quote because I fear it is still valid. I have the uncanny feeling that I still suffer from the same flaws. My current novel may prove to be just as much “the work of an apprentice” as my earlier novel attempts. Have I learned nothing in the decades since?

I haven’t even enumerated all of the flaws I exhibited back in the day. For example, when I submitted a revised version of AGAINST THE MALUII, retitled DEVIL FROM THE TOWER, to Ballantine books in June of 1985, the one line from the response I can quote from memory (I’ve misplaced the original rejection letter, alas) is: “We don’t like your main character and don’t think anyone else will either.”

Ah, yes, the kind of flaw which needs to be corrected. I did, in fact, rewrite the book a second time, but as I wasn’t convinced I had solved the problem, I put it aside. In all I wrote five or six novels, the majority of them science fiction, and all were rejected. I stopped writing novels.

Having been active in science fiction fandom since 1970, by the 1990s all my writing efforts were devoted to newsletters and fanzines. I became something of a fannish historian. I won a couple of Aurora awards for these activities. But all the while in the back of my mind was a nagging awareness I was ignoring my bucket list.

In 2016 I decided that if I can’t get published as a writer, I’d become the next best thing, a publisher and an editor. And so I launched POLAR BOREALIS Magazine. To date I have published 19 issues (will publish #20 this month) containing a total of 171 poems and 188 short stories. For this I have won an additional two Aurora Awards. And this year I began publishing POLAR STARLIGHT Magazine, edited by Rhea Rose, featuring sixteen poems per issue. The fourth issue will also come out this month. Fair to say this activity gives me a great and satisfying sense of accomplishment.

And yet, and yet, what about my half-century-plus dream of publishing one or more SF novels? It has always been number one on my bucket list. How much longer will I put this off?

And now we come to it. I’m seventy years old. No time to waste. It’s now or never.

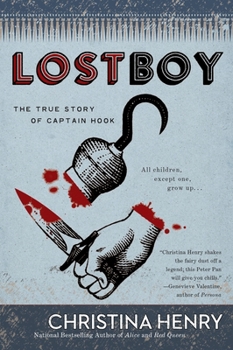

On thinking this over I realized it doesn’t actually matter if I retain all the flaws of my youthful writing style as noted in the quotes above. This is the era of self-publishing. At the very least, at a bare minimum, I can produce one or more print-on-demand soft cover novels to fit on my bookshelf. I already have a number of professional artists willing to create those lurid covers I dreamed of. Maybe no one else on Earth will buy my books, but I will! After all, the vision I experienced at sixteen years-of-age implied nothing about anyone else actually buying and reading my books. It was narrowly focused on me simply admiring my own works. Modern publishing practices make this doable!

But how do I do it? I’m no longer an enthusiastic young man in good health, bursting with energy and stamina. Obviously I need to make concessions to my current state of being.

PROBLEM #1: For instance, my memory officially sucks. They say “live in the moment.” I have to. I can’t do otherwise. I don’t remember what I did yesterday, let alone last week. I have to take notes to keep track of things.

So, no problem. Every good novel depends on extensive research and voluminous notes. But that can be an endless rabbit hole with no end in sight, often producing more pages of notes than the proposed novel itself. Doing research can often be a waste of time, an excuse not to write, a horrible practice of merely transferring information from a resource to your own folder without actually making use of the information.

Here’s the real kicker. If I wind up with say, a thousand pages of notes, by the time I finish going through it I will have forgotten all of it. Even if I just peruse one page, it won’t stick in my mind for more than an hour. My research is useless to me. (On the bright side, I really enjoy reading the books in my collection because I’ve forgotten so much that picking up any one of them is like reading it for the first time.) Even creating outlines and character studies is like sculpting with fine sand. It all slips through my fingers once I walk away from my desk.

SOLUTION #1: Don’t bother with research. I just sit down at my laptop and start writing. If I need to find the correct spelling of “Tiglath-pileser” I will save that for the second draft rewrite. What little research I end up doing will be focused, in-the-moment correction stuff. No need to read volumes of Assyrian history in advance. Besides, not doing research saves a heck of a lot of time, something I may not have available in abundance anyway, depending.

PROBLEM #2: If my memory consistently fails, how the heck can I think about my novel? A writer like Theodore Sturgeon pondered his projects so intelligently and cogently in such incredible depth that by the time he wrote his first draft it was in fact the final draft ready to be sent to the publisher. (I was present when his wife explained his technique of composition.) To put it mildly, I can’t do that.

SOLUTION #2: Don’t think about my novel. When I sit down to begin a writing session I have only a vague idea what I’m going to write. I make it up as I go along. What I’m doing is relying on my subconscious mind. Before going to bed I reread what I wrote the day before. Then I let my subconscious stew over it while I sleep. I start writing as soon as I’ve gotten up the next morning and made my first cup of coffee. Definitely a form of automatic writing. Lucid dream-state writing to a degree. Once finished, I go back to bed. When I subsequently get up I’m often surprised by what I’ve written.

PROBLEM #3: I don’t know what I’m writing about. My mind is pretty much an empty void. Consequently I’m often easily distracted by my own thoughts, to the point of not being able to concentrate. Pretty close to a “Oh, look! A Squirrel!” mentality. Especially since, staring out the window above my writing desk, I often see squirrels.

SOLUTION #3: Rely on my ignorance. My main character, though cunning and resourceful, doesn’t believe in cluttering his mind with knowledge. Nobody in my dystopic novel can figure out what’s going on anyway. Everything is collapsing too fast to keep track of. Instinct and adaptability are the survival traits required, not knowledge. Perfect. I’m really good at projecting ignorance.

PROBLEM #4: But the book has to be about something. The hypothetical reality of this future history needs to be buttressed with facts and an internal logic consistent with its premise.

SOLUTION #4: I’ve been around for seventy years. Buried in my subconscious mind are all sorts of biased opinions, half-formed prejudices, and inaccurate observations on just about every subject under the sun. Aztec Empire? Freudian theories? Nuclear reactors? I know all about them, or at least my subconscious mind thinks it does. Just a hodgepodge of inadequate impressions gained over a lifetime, but good enough for my needs. I let my subconscious throw whatever it dredges up into my manuscript as it sees fit. Such misinformation, being engrained in my brain, has an air of convincing authenticity which lends veracity to the text..

PROBLEM #5: But everything about the methodology of writing a novel is so complicated and self-sabotaging.

SOLUTION #5: Not if you don’t think about it. The trick is to keep things simple. I sit down. I type a sentence. I stare at it. Eventually another sentence suggests itself. I repeat the process. Soon I visualize it as a scene unfolding before my mind’s eye. At that point I simply describe what I see. But not too much description. That’s the sort of thing readers skip past. So I keep my paragraphs short, and rely on dialogue and inner monologue to carry the story. Readers pay more attention to those things. Easier to relate to, maybe. Makes for a fast-paced, easy-to-read novel.

PROBLEM #6: Inevitably an off-the-top-of-the-head, pantser-style (writing by the seat of one’s pants) manuscript is full of errors, contradictions, typos, misplaced characters and what-not. What could be more frustrating than realizing the paragraph you’ve just written is not what you intended to express and in fact doesn’t even make sense?

SOLUTION #6: Don’t worry about it. Don’t rewrite it. Just leave as is and carry on. Plenty of time to attempt to figure out what you meant to write once you start the second draft. The main thing is to get the gist of your novel down and complete as quickly as possible. Don’t rewrite. Don’t even correct typos. Get it done. Then correct.

PROBLEM #7: But I get so tired writing. When’s a good time to stop? How long should a writing session be? If I leave it open-ended I may wind up writing beyond my inspiration and forcing myself into writing laboured and boring prose.

SOLUTION #7: I write exactly three pages. The number of words varies, but is always over a thousand words. Each chapter is three writing sessions long or nine pages. This greatly aids in building suspense and tension, not to mention creating hooks to make people want to immediately read the next chapter. At least, that’s what I prefer to believe.

RESULT: A worry-free, stress-free, practically thought-free method of writing. Perfect for an old guy like me. Might work for you, too.

One last piece of advice. Don’t talk about your writing. Don’t explain it, justify it, or wax poetic about it. Nothing kills your inspiration faster than exposing it to the cold light of someone else’s out-of-context incomprehension. Then your brilliant, shining ideas come across as flat, dull, and boring. Talk about writing too much, and you’ll give up writing.

All you know about my book is that it takes place sometime in the future when the world is going to hell in a handbasket and that somehow it involves Assyrians (who were historically quite good at giving hell). In other words, it’s flat out weird and distinctly oddball.

Hopefully this will make you want to buy it whenever the heck it becomes available.

In the meantime, for you writers out there, I hope you found my advice useful. Or at least amusing.