Hasn’t it been a long, hot summer? Right now, as I write, it’s raining, which I hope will quell some of the 250 forest fires burning in British Columbia right now. Thank goodness the smoke has cleared in our area. We’re still trying to self-isolate as much as possible, but temperatures higher than have been recorded in BC before have made us swelter in place (we don’t have air conditioning). I hope your summer has been better than that! One way of escaping the heat and isolation is to watch TV or read—and what better thing to read than genre fiction?

Figure 1 shows the cover to a new anthology (available on Amazon dot wherever you live; in my country, it’s Amazon dot ca; in the US it’s Amazon dot com; and so on) not about the pandemic we’re suffering through, but about apocalyptic pandemics in general. Now, you might think reading an anthology about death and disease is counterintuitive, but as long as you don’t try to read it all at one sitting, it does (to me, at least) seem to distract from the very real pandemic—so far, short of apocalyptic, thank Ghu—we’re in.

This is a very good anthology, from Skywatcher Press is edited by Matthew Hollis Damon (not the film Matt Damon!) and Marie Lanza, and is dedicated to the late Robert B. Damon. It’s just come out, and is the first of three “Unleashed” anthologies. The second one will be published fairly soon, called Terror Unleashed Volume 2; the third one will be The Dead Unleashed Volume 3. I was sent an ARC (Advanced Reader’s Copy) of this in exchange for a fair review, I’ll disclose here. (Just FYI, unless a book [fiction or whatever] is extremely bad—egregiously bad—I try not to leave a really negative review, but will always try to be as honest as possible in stating my opinions.) The anthology contains sixteen stories, ranging from “okay” to “very good,” and for the price you pay for an ebook (it’s also available as a paperback, according to Amazon), which is about $3.85 Canadian, can’t be beat.

I won’t rate every story in the book, but will talk about some of the ones I thought were very well worth reading. Here is a list of all the stories:

“Patient Zero,” Claire Davon

“A Game of Solitaire,” Hillary Lyon

“Whatever It Takes,” Victoria Hancox

“The Far Edge of Sixteen,” Matthew Hollis Damon

“Insanire,” Marie Lanza

“The Ribbon,” Kara Race-Moore

“If They Bleed,” Rachel Roth

“Boys,” Rich Restucci

“The Fever and the Thaw,” Richard Clive

“The Isolated Life of Gerald Connors,” David Greske

“They Wiggled and Jiggled and Tickled Inside Her,” Benjamin Langley

“Daddy’s Sick,” Chris Grillot

“The Greasy-Feast Outbreak,” Tim O’Neal

“Side Effects May Vary,” Tracy Cross

“The Last Days of the Plague,” Sara Century

“Everything Had Been Normal,” DJ Tyrer

““Patient Zero,” by Claire Davon, is about a physician working on people in the Miami-Dade County area, whose wife must take a vacation trip without him. He has to work, but is happy to take her to the airport for her trip. This one’s a bit of a shocker, and a great start to the anthology.

“Whatever it Takes,” by Victoria Hancox, postulates a world in which a plague takes all babies, then adults over a certain (fairly young) age. Claire has been taught to do whatever it takes to survive a pandemic, but she’s up against Kurt, who has decided that evil is the survival trait. And he’s got quite a following. Maybe a bit long, but well done and a bit subtle.

“The Far Edge of Sixteen,” by editor Matthew Hollis Damon, is a good one. Nick and Callie have a daughter, and have been able to self-isolate while the pandemic raged, people died, and food became scarce. But it’s getting to the point where you don’t dare let anyone close to you for fear they’ll infect you. But at what point is how much violence justified because of fear? A nice little chiller.

“Insanire,” by Marie Lanza, co-editor, showcases the kinds of mental issues that can arise, or be exacerbated, during a much deadlier pandemic than we’re living through. I might have argued for a bit more conclusive ending, but you can’t have everything. Well written.

“They Wiggled and Jiggled and Tickled Inside Her,” by Benjamin Langley, is, in a way, the reverse of the previous story, “Insanire.” Again, it’s about mental adjustments to a deadly pandemic. Some adjust one way, and some a very different way. A very different way.

“Side Effects May Vary,” by Tracy Cross, gave me a bit of a chuckle, but I can’t explain why without spoiling the story for you. It’s all about the writing.

The above are about a quarter of the stories in this book; there are others as good, or nearly as good that I haven’t touched on. But you know I like to leave things for my readers to discover, and I promise there are worthwhile stories not mentioned here. If you read it and enjoy it, you should also leave a rating and a review on Amazon.

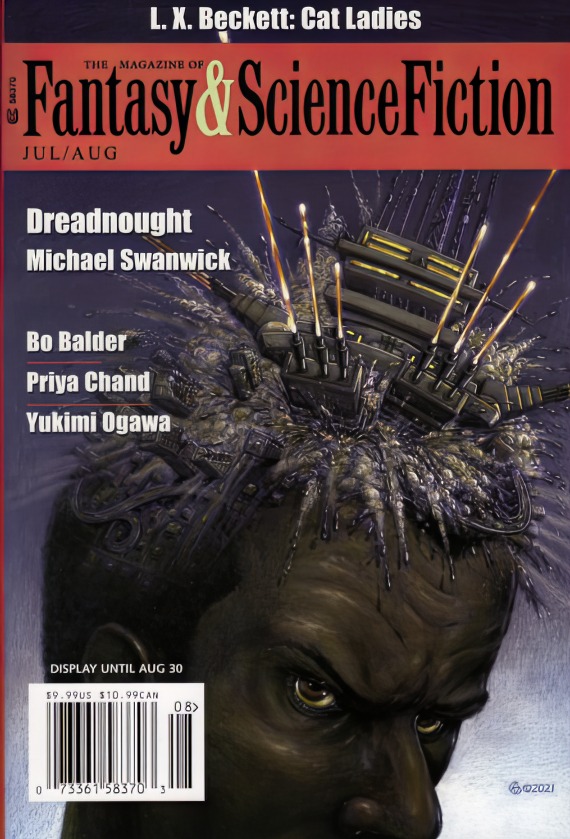

I’m late again with my July/August F&SF review. I can only plead tiredness; some days I seem to have little energy; it’s all I can do to walk a few blocks with my wife each day. Gonna have to hit the doctor-bot up and see if he can prescribe some uppers or something. The extra iron pills don’t seem to be pepping me up.

Because I’m running long here, I’ll hit what I think are the highlights of this issue, and not comment on each individual story. There are, I believe, nineteen stories and one poem, plus the usual book reviews by Charles de Lint, Elizabeth Hand, James Sallis and Michelle West, “Curiosities,” which looks at odd books of enduring interest, humor by Paul Di Filippo, and film commentary by David J. Skal.

This is the second issue, I believe, edited entirely by new editor Sheree Renée Thomas. Her editorial is partly about Kahlil Gibran (author of cult favourite The Prophet) and his poem “On Freedom.” I haven’t read that poem (or if I have, it was many years ago), but it appears to be about becoming free both within and without—discarding useless and confining parts of ourselves and our environments. While I applaud the sentiment, I feel I’m as free as I can get, and might caution people about “throwing the baby out with the bathwater,” if any of you remember that old saw. (Hey, I’m old enough to remember the “generation gap” of the sixties!)

“Whatever Happened to the Boy Who Fell into the Lake?” by Rob Costello, is about Tick, who’s too young to know whether he’s straight or gay (or other, I guess). That does figure into the story, but the story is only partially about that; it’s about parental abuse, it’s about relationships, and it’s about discovery. I thought it was really well written.

I found “Dreadnought,” by Michael Swanwick (the cover story) rather confusing. It starts “The troll lived under the overpass,” and you expect some kind of fairy-tale fantasy. Instead, you get a fairly straightforward story about a homeless man who drinks a lot and gets harangued a lot by a religious guy who’s accompanied by a kid called “Cthulhu.” A bit of a spoiler here: it’s an apocalyptic tale, but instead of a religious apocalypse, we get… what? A giant war machine? Hello? I’m not following. Weird.

“Her Garden, the Size of Her Palm,” by Yukimi Ogawa, is by a woman “who lives in Tokyo and writes in English but who never speaks the language.” I can see why she doesn’t—anyone she talked to would be totally confused. This story’s like R.A. Lafferty and Cordwainer Smith had a baby with Philip K. Dick, and the baby wrote the story. Does that qualify it as fantasy? Or am I missing something (hey, that’s entirely possible!). I liked it, but I’m still not sure what I liked!

“Tulip Fever,” by Bo Balder, is one of my favourite stories in the issue. Pure SF, it’s a future story of someone who lives on a giant floating machine, “The Slat,” that harvests microplastics from the Northern Pacific Gyre. Apparently plague (caused by microplastic allergies and the like) and other environmental issues have caused worldwide collapses or economies and countries, and there are a few Humanity Enclaves left. Jones is a Tulip; her face is mottled with greens, pinks, blues, and lavenders, but as the child of two people affected by the “plastics plagues,” she is immune. Her uncle, a refugee from The Netherlands (a country wholly underwater) rules The Slat, but Jones is afraid he will sell her to the Slavers, who will either enslave her or grind her up to feed her immunity to others. Well written indeed!

Another of my faves this issue is “(emet),” by Lauren Ring. Why is it a favourite? Well, for one thing, it’s a perfect (and I don’t say that lightly) melding of fantasy and sf in one story. Chaya is a computer programmer who lives in her own little spot in the LA area, but she is something besides: a Jewish witch (her word, not mine) who creates clay golems and animates them programmatically by engraving “emet” (“life”) on their foreheads and telling them what tasks she wants them to perform. When they have completed their tasks, she runs a program that erases the “aleph” (first character of the emet) and turns it into “met,” which means “death.” How great a concept is that? A character from Jewish folklore (if you remember, Rabbi Loew made the most famous one), being created and run by a computer programmer? It’s a well-done story, and both the golems and Chaya’s job are germane to, and vital to, the plot and its conclusion.

“The Penitent,” by Phoenix Alexander, is pure fantasy. The story is a loop. The protagonist goes through a number of iterations and changes, in order to put things in order… to misquote an old TV ad, to “be all that he/she/it can be.” Weird, but nicely written.

“And for My Next Trick, I Have Disappeared,” by Chimedum Ohaegbu is a puzzlement. Written with inline graphics that make it appear to be a musical piece, it’s about a woman named Adachukwu Ejiofor (don’t you just love these musical names? They go with my longtime favourite “Chiwetel Ejiofor,” whom you might recall from “Firefly” the movie) who rides a night bus to Calgary (Alberta) but appears to be turning into the bus? I’ve read it several times and am still not sure what happened. But it’s sure fun to read!

“Woman, Soldier, Girl,” by Priya Chand, somehow recalls the bad old Colonial days of The Raj in India, which I’m sure was its purpose. I’m not well-versed enough in the history of that time and place to know what’s real and what’s SF, but it’s a very good story.

And for my final review (of course I’ve left a number unreviewed; I hope you will buy it and read it to discover what you’ve missed), I’d like to talk about “Mamá Chayo’s Magic Lesson,” by Tato Navarrete Díaz. It’s from the Mexican tradition by a person who lives in or near the Sonora Desert of that country. I was intrigued by her image of a hut with four legs that owed nothing at all to the Russian “Baba Yaga” folklore. The story, which has a tale within a tale, concerns magic, and what witches can and can’t, should and shouldn’t do. Makes a lot of sense; if there is such a thing as witchcraft (I’m a Doubting Thomas), it would probably have rules like this.

There are several good stories in this issue that I haven’t touched on, but I’m sure you’ll discover them when you get your own copy (f&sf.com).

Comments on my column are welcome. Comment here, or on Facebook, or even by email (stevefah at hotmail dot com). All comments, positive or negative, are welcome! (Just keep it polite, okay?) My opinion is, as always, my own, and doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of Amazing Stories or its owner, editor, publisher or other columnists. See you next time!

Steve has been an active fan since the 1970s, when he founded the Palouse Empire Science Fiction Association and the more-or-less late MosCon in Pullman, WA and Moscow, ID, though he started reading SF/F in the early-to-mid 1950s, when he was just a sprat. He moved to Canada in 1985 and quickly became involved with Canadian cons, including ConText (’89 and ’81) and VCON. He’s published a couple of books and a number of short stories, and has collaborated with his two-time Aurora-winning wife Lynne Taylor Fahnestalk on a number of art projects. As of this writing he’s the proofreader for R. Graeme Cameron’s Polar Borealis and Polar Starlight publications. He’s been writing for Amazing Stories off and on since the early 1980s. His column can be found on Amazing Stories most Fridays.

Recent Comments