A vast ocean liner points down towards us, its stern in the sky and its prow a short distance from the ground. At first glance an observer might assume that the ship is plummeting from the stratosphere and about to crush the two unfortunate figures standing below. On closer inspection, however, it is revealed that one of these implausibly-foreshortened men is somehow holding the entire shift aloft in one hand. The July 1929 issue of Science Wonder Stories had arrived, hot on the heels of the debut number.

A vast ocean liner points down towards us, its stern in the sky and its prow a short distance from the ground. At first glance an observer might assume that the ship is plummeting from the stratosphere and about to crush the two unfortunate figures standing below. On closer inspection, however, it is revealed that one of these implausibly-foreshortened men is somehow holding the entire shift aloft in one hand. The July 1929 issue of Science Wonder Stories had arrived, hot on the heels of the debut number.

Notably, the cover this month illustrates not one of the stories but rather Hugo Gernsback’s editorial – an indication of Science Wonder Stories’ commitment to its non-fiction portion, perhaps. Entitled “The Wonders of Gravitation”F the editorial discusses the effects of taking heavy objects to bodies with gravity lower than that of our planet:

One of the largest mobile objects at the present time on earth is undoubtedly the monster trans-Atlantic Steamship, Leviathan, which weighs 60,000 tons, or 120,000,000 pounds. It is interesting to note that, large as this ship is, it would be quite possible under certain conditions for a single human being to lift it without taxing his strength unduly. Of course, this statement has to be taken with a grain of salt, because in the first place, it would be necessary to transport the Leviathan to a point in space where it was possible to perform the experiment, and second, granted that even that were possible, it would be most difficult for a human being to get a good grip on the ship itself. Perhaps he might hold the ship up by the end of the mast, using the top of the mast as a handle.

In terms of the issue’s fiction, however, there are no low-gravity worlds to be explored. Instead, the authors take us on a tour of a subterranean realm, a lost civilisation in the desert, an ancient world at the time of Atlantis, and the battlefields of a not-too-distant future…

The Alien Intelligence by Jack Williamson (part 1 of 2)

Physician Winfield Fowler receives a radio message from his friend, Dr. Horace Austen (“the well-known radiologist, archeologist, and explorer”) who had previously gone missing during a trip to Australia’s Great Victoria Desert. The message is strange, mentioning a crystal city, alien terrors and a woman named Melvar, and implores Winfield for help.

Physician Winfield Fowler receives a radio message from his friend, Dr. Horace Austen (“the well-known radiologist, archeologist, and explorer”) who had previously gone missing during a trip to Australia’s Great Victoria Desert. The message is strange, mentioning a crystal city, alien terrors and a woman named Melvar, and implores Winfield for help.

Corresponding with other radio enthusiasts, Winfield pinpoints the distress call to a specific location: “The lines intersected in the Great Victoria Desert, at a point very near that at which Wellington located the Mountain of the Moon, when he sighted it and named it in 1887”. And so our hero sets off on an expedition; while camping in the desert, he encounters eerie phenomena (“That unearthly laugh, and the footprints! Was there a land of madmen behind the mountain? And what was the thing that had come and gone in the night?”) but all of this is just the beginning of his adventure. Arriving at his destination, Winfield finds a wondrous sight:

I stood on the brink of a great chasm whose bottom must have been miles, even, below sea level. The farther walls of the circular pit—they must have been forty miles away—were still black in the shadow of the morning. Clouds of red and purple mist hung in the infinities of space the chasm contained, and completely hid the farther half of the floor. Beneath me, so far away that it was as if I looked on another world, was a deep red shelf, a scarlet plain weird as the deserts of Mars.

To what it owed its color I could not tell. In the midst of the red, rose a mountain whose summit was a strange crown of scintillating fire. It looked as though it were capped, not with snow, but with an immense heap of precious jewels, set on fire with the glory of the sun, and blazing with a splendrous shifting flame of prismatic light. And the crimson upland sloped down—to “the Silver Lake.” It was a lake shaped like a crescent moon, the horns reaching to the mountains on the north and the south.

While here, Winfield encounters strangely-hued vegetation, coloured lights that dart about as though intelligent, and then a glimpse of the region’s inhabitants:

I saw a line of men, queerly equipped soldiers, marching in single file over the nearest knoll. They seemed to be wearing a closely fitting chain mail of silvery metal, and they had helmets, breastplates and shields that threw off the sunlight in scintillant flashes of red, as if made of rubies. And their long swords flashed like diamonds. Their crystal armor tinkled as they came, in time to their marching feet. One, whom I took to be the leader, boomed out an order in a hearty, mellow voice. They passed straight by, within fifty yards of me. I saw that they were tall men, of magnificent physique, white-skinned, with blond hair and blue eyes. On they went, in the direction of the fire-topped mountain, until they passed out of sight in a slight declivity, and the music died away. It is needless to say that I was excited as by nothing that I had seen before. A race of fair-haired men in an Australian valley. What a sensational discovery

Finally, Winfield comes across what he takes to be the Crystal City described by his missing friend (“A city of crystal! Prismatic fires of emerald-green, and ruby-red, and sapphire-blue, poured out in a mingled flood of iridescence from its slender spires and great towers, its central ruby dome and the circling battlements of a hundred flashing hues.”) He then meets a beautiful woman, who turns out to be Austen’s acquaintance Melvar; having communicated with the explorer, she speaks English and recognises Winfield. He soon falls in love with her: “Once her golden hair brushed against my cheek. Her nearness was very pleasant. I knew that I loved her completely, though I had never taken much stock in love at first sight.”

Melvar shows Winfield around the Crystal City – Astran, as it is known – and he learns that it was built from diamonds, prompting him to speculate that the civilisation at one point had a method of synthesising precious stones in such quantity as to be used as building material. But the technology of Astran has destructive as well as creative aspects, with Winfield witnessing a large boulder destroyed by a slender blue beam. Melvar explains that this is used to fight off the strange lights – known as Krimlu – whom her people believe to be vengeful spirits of the dead. The Krimlu are one of two groups feared by the people of Astran, the others being the Purple Ones. Before long, Winfield has the dubious honour of seeing the corpse of a deceased Purple One:

The crowd turned eagerly to the new arrivals. I saw that they were a band of soldiers, possibly the same that had passed me in the morning. Slung to a pole carried between the foremost two, was a strange thing. Weirdly colored and fearfully mutilated as it was, I saw that it was the naked body of a human being. The head was cut half off, and dangling at a grotesque angle. The hair was very long and very white, flying in loose disorder. The features were withered and wrinkled, indeed the whole form was incredibly emaciated. It was the corpse of a woman. The flesh was deep purple! As I stood staring at the thing in horror, there was laughter and cheering in the crowd, and a little child ran up to stab at the thing with a miniature diamond sword.

Winfield then learns that Astran is not to be especially forward-looking in terms of religion. “They did not like the things Austen told of the world outside,” says Melvar, “for the priests teach that there is no such world.” Melvar and her younger brother Naro turn out to be orphans, their father having been taken by the Krimlu while their mother was sacrificed by Jorak, the city’s fearsome priest. Melvar herself ends up as a candidate for sacrifice, prompting Winfield and Naro to set off to rescue her. After some derring-do (“Once a man sprang suddenly at us from behind a sapphire pillar, diamond sword drawn. My pistol exploded in his face and blew his head half off”) they are able to slay the sacrificial priest in the nick of time:

As we came around the sphere he was holding up the vessel and repeating a strange chant in a monotonous monotone. At sight of us he dropped into alarmed silence, with an ugly scowl of hate and fear distorting his harsh features. For a moment he stood as if paralyzed, then he rushed toward the silent girl as though to empty the contents of the crystal pitcher upon her. I fired on the instant, and had the luck to shatter the vessel, splashing the shining silvery fluid all over his person. The effect of it was instantaneous and terrible. His purple robe was eaten away and set on fire by the stuff; his flesh was dyed a deep purple, and partially consumed. He tottered and fell to the floor in a writhing, flaming heap.

Winfield then sets off in search of his exiled friend Austen, accompanied by the curious Melvar (“She asked innumerable questions… on such subjects as the appearance of a cat, and Fifth Avenue styles of ladies’ garments”) and her brother. Along the way Winfield experiments with the strange silver liquid, finding out that it has the property of turning his skin purple, and also encounters a coloured mist that has a strange psychological effect on him: “it seemed that I felt the power of a vast and alien will stealing over me, seizing command of me, making me the slave of itself.” This soon wears off, however.

The trio encounters another Purple One, but Winfield is able to fight the attacker off with the aid of Melvar (whom he has taught to use firearms: “She swung up the automatic with a quick, sure, graceful movement. She was like a beautiful goddess of battle, with blue eyes shining brightly, and golden hair gleaming in the sun”) and the sword-wielding Naro. Next, they witness the landing of a cylindrical metal craft, after which the occupants emerge:

But on the instant we moved a great oval space swung out of the side of the cylinder. We saw that the door and walls were of a bluish white metal, and were very thick. It was very dark inside. A blood-congealing, eerie laugh sounded out of that darkness, and I shuddered. Quickly five human-like figures leaped one by one out of the oval doorway. With heart-chilling fear, I saw, by the flickering light of the burning thicket, that long white hair hanging about faces wrinkled and hideously aged, with toothless gums, red glaring eyes, and skin that was purple. Without a moment’s hesitation, the five naked monsters rushed down upon us.

The fire was fast blazing higher and burning rapidly into the brush between us and the cylinder, and we could see the purple beasts quite plainly in its light. And they were hideous to look upon. They came toward us with monstrous, springing bounds, actuated by some extraordinary force. Their muscles must have been far stronger than those of men, perhaps as strongly constructed as those of insects. Or, since muscular force depends on the intensity of nerve currents, perhaps their nerves were extraordinarily excited. And there was something insect-like in the way life had lingered in the body of the one we had killed, when it had already many wounds that should have been mortal.

The editorial introduction to The Alien Intelligence compares the story to A. Merritt’s The Moon Pool, and it is not hard to see where Merritt’s writing style may have been an influence on author Jack Williamson. Anyone who has read The Moon Pool will remember its repeated emphasis on mysterious coloured lights, and Williamson fills his lost civilisation with a similarly alluring jewels-in-the-darkness palette: “The lake gleamed like quicksilver and light waves ran upon it, reflecting the sunlight in cold blue fire. It seemed that faint purple vapors were floating up from the surface. Set like a picture in the dark red landscape, with the black cliffs about, the argent lake was very white, and very bright.”

Williamson would later become known for his work in space opera, and it is interesting to see his eagerness to give his Merritt-esque fantasy a backbone of science fiction. The story’s first instalment ends with the protagonist mulling over the technological implications behind all that he has witnessed:

While my understanding of it all was far from complete, I was able to verify a previous idea—that the strange vessels were driven by use of the rocket principle. It seems that the silver fluid was decomposed in the machine, and that the purple gas it formed, at a very high temperature, was forced out through the various tubes at a terrific velocity, propelling the ship by its reaction. The whistling roar of the things in motion was, of course, the sound of the escaping gas, and the red-purple tracks were merely the expelled gas hanging in the air. The green globe in the forward end may have been the objective lens for a marvelous periscope. At any rate the walls of the forward part of the shell seemed transparent. And the periscope must have utilized infra-red rays, for the scene about us seemed much brighter than it, in reality, was.

The Reign of the Ray by Fletcher Pratt (part 2 of 2)

Fletcher Pratt’s vision of death ray-enhanced near-future warfare (jointly attributed to his non-existent co-writer Irvin Lester) reaches its concluding instalment. This begins in 1934, in the heat of combat at a Polish battlefield., and once again Pratt appears interested less in visceral violence and more in the broader technological implications of the death ray: “with the disappearance of the high-velocity bullet, and the necessity of some protective coating against the Adams Ray, armor made its reappearance in the form of light-weight steel plates, covering the entire body and plated on the inside with a thin film of lead to keep the ray out.”

Fletcher Pratt’s vision of death ray-enhanced near-future warfare (jointly attributed to his non-existent co-writer Irvin Lester) reaches its concluding instalment. This begins in 1934, in the heat of combat at a Polish battlefield., and once again Pratt appears interested less in visceral violence and more in the broader technological implications of the death ray: “with the disappearance of the high-velocity bullet, and the necessity of some protective coating against the Adams Ray, armor made its reappearance in the form of light-weight steel plates, covering the entire body and plated on the inside with a thin film of lead to keep the ray out.”

After this we cut to “the war behind the war” as the story details various political developments from 1932 to 1936 – note that Pratt was a military historian as well as a fiction author:

To descend from the general to the particular, take the case of England. London was practically wiped out by the Soviet bombers but Parliament was not sitting and most of its members escaped to convene at Canterbury later. They had to build up a new government, for the Cabinet and all the royal family but the infant Princess Elizabeth perished with the hundreds of thousands of humbler persons in the great catastrophe.

A Regency was named, of course. Its continued existence is due to the premature death of the unhappy princess. Amid the turmoil of a great war there was no time to examine any of the various claimants to the crown. To have settled on any one of them would have provoked disaffection and perhaps civil disturbances at a moment when the government already had much to deal with. It was determined to keep the loyalty of all parties by the legal fiction that the little Queen was still living. And when the war had ended British conservatism would hear neither of abolishing the crown nor of terminating the sham. Consequently, the fiction of a Queen Elizabeth II, alive and reigning, is persisted in to this day, with the Regency directing her affairs. If she really were alive she would be something like a hundred and thirty years of age.

Various events take place across Europe, from Ireland bombing parts of Britain to France re-establishing its monarchy, while America and its allies across the Atlantic form an international parliament: “No one, not even Woodrow Wilson, would have dreamed of such an international parliament as the Alliance now has, or an international executive head, able to enforce his order, like Lord Melton” declares the President.

As well as warfare and politics, Pratt is clearly interested in the advance of media technology. We learn that radio has brought a vast improvement in education: “When I was a lad we had to spend six or seven hours a day in school”, says one character. “Now children get it all in their sleep by radio. Why, it’s done away with all that was dangerous in child labor without the necessity for legislation.” The rise in radio is accompanied by a drop in literacy; in one scene, the President and his Intelligence Chief Adsill argue over whether or not this this is a significant drawback:

“It used to be an advantage to read and write, just as it used to be to handle a gun. But the Adams Ray has eliminated the gun, and the pictograph has done away with the book. After all the spoken word is more effective than the written. And now that we can listen to and see our stories on the pictograph, why should we bother with clumsy and dirty books, which always imposed a barrier of type between the mind of the author and that of the reader?”

“Nonsense!” declared the Intelligence Chief firmly. “The pictograph is valuable only to readers of light fiction. It does away with all deep thought, with philosophy, with all the amusements of intelligent people. You can get more of Kant or Spinoza from a small book than from half a dozen pictographs.”

Adsill’s augment is refuted by a “new edition of the dialogues of Plato just issued by the Doubledays. You can put it in your pictograph machine and actually hear and see Socrates confounding the sophists under the Golden Porch. It’s ten times better than reading the lifeless printed words.”

As the story progresses it introduces a new character in Harve Mellen, who is forcibly thrown into this futuristic landscape after being released from jail. He finds himself in a strange new world where Bolsheviks perform raids at night, and he is expected to exchange labour tickets rather than money. He is ordered to speak to one Sergeant Gowan for more information about current affairs (“Harve realized with a sense of acute shock that Sergeant Gowan was a woman, and with eyes opened by the discovery glanced at the rest of the group. Surely that was a woman, too, and that one over there”).

Despite his initial bewilderment, Harve comes to speak approvingly of the vast changes to society. “Our civilization was elegant because it was becoming decadent”, he argues. “Everybody was too busy having a good time to think of serious things.” After complaining that “Life was getting itself filled up with little hypocrisies and lies, and growing more and more rotten at the bottom” he concludes that “We needed this dip into the primitive to clear the air.” He cites the work of Charles Darwin and the eugenicist Ellsworth Huntington, who “tell you that a race always declines unless natural selection has a chance to operate. Under a civilization like the one we are leaving behind, the unfit are preserved and even get to high places.” These “unfit”, Harve says, are now being rightly eliminated:

“The unfit are going. Who would have dared to suggest that criminals be sterilized in the old days? Or idiots? But it’s done every day now. And look at the decrease in insanity. There is fighting going on but no murder—at least not as there was. The mechanical basis of our civilization will be more secure, too. Think of the tremendous waste there used to be in the old days, when a man could buy an automobile one month and trade it in for another the next. Now if he wants to get a new machine, whether it’s a Wagstaff or an auto, he has to get permission, and all the time and labor that went into producing the unnecessary machine is put on something useful.”

Sergeant Gowan offers some protest to Harve’s views. She replies that the new society is failing to produce any new books or art of note; Harve assures her that this shall arrive in due course. She also argues that democracy has gone: “Don’t you think the men who wrote the Constitution would hate to see us now, with everyone in the country enrolled in the army and under orders? And where are our state and local governments? There hasn’t been a mayor of Pittsburgh in four years.” Harve begs to differ:

“But democracy is not so much a form of government as the spirit behind it. England was as democratic as it could be under a king. Even before the war the old form of a big, unwieldy congress always quarrelling with and impeding the president was breaking down. There were too many laws. Honestly don’t you think the present system is better? No one is losing anything by not voting. Here I am, for instance, just out of prison, and I’m already a captain. There was nothing like it before.”

The Sergeant remains unconvinced. “I’m afraid we’re going to get something like… a mere rule of efficiency, in which the individual will be a kind of robot”, she says, and receives the following reply:

Harve Mellen mused. “That’s on the knees of the future,” he said finally. “Perhaps you’re right… Still—” he flung out his hand in an expansive gesture. “This doesn’t look like it.”

And so concludes Fletcher Pratt’s vision of warfare in the 1930s. The Reign of the Ray is nothing if not ambitious: while many writers would have contented themselves with the image of people and vehicles being blasted away by the death-ray, Pratt delves into the geopolitical complexities behind the high-tech conflict.

His observations and predictions are often intriguing, although his story does have the flaw – a glaring one, in hindsight – in that it fails to address the threat of fascism. The portrayal of communism as the one significant menace to peace across Europe, the brief and comparatively favourable depiction of Mussolini in the first instalment and – above all – the rosy vision of a eugenically-oriented future articulated by Harve Mellen at the end all provide an unsettling undercurrent to the tale.

“The Boneless Horror” by David H. Keller

Set in an antediluvian world, this story depicts the power politics between the kingdoms of Gobi, Mo and Atlantis. The Emperor of Gobi hopes to destroy Mo; the Royal Mathematician, Royal Engineer and Royal Geographer have devised a plan of doing so by literally undermining the rival kingdom, digging vast tunnels below Mo and filling them with explosives. The one drawback is that the process will be long – so long that, under a natural lifespan, the Emperor would not live to see Mo fall.

Set in an antediluvian world, this story depicts the power politics between the kingdoms of Gobi, Mo and Atlantis. The Emperor of Gobi hopes to destroy Mo; the Royal Mathematician, Royal Engineer and Royal Geographer have devised a plan of doing so by literally undermining the rival kingdom, digging vast tunnels below Mo and filling them with explosives. The one drawback is that the process will be long – so long that, under a natural lifespan, the Emperor would not live to see Mo fall.

The Emperor enlists the aid of an Atlantian physician named Heracles who knows the secret of lengthening a person’s life. Using the blood of a bull, the fat of geese, the oil of a turtle and the flesh of an unspecified fish, he is able to create a substance that does for humans what royal jelly does for a queen bee.

Unbeknown to the Emperor, Heracles is secretly in league with Mo. When the ruler throws a special month of entertainment “consisting of feasting and amusements and loving of strange women and the delightful killing of slaves in strange and unusual ways” Heracles takes the opportunity to spike the jelly. The new additives include opium (to prevent the victims from realising what is happening) and a medicine with a terrible effect on the recipient’s body: “This medicine, given in proper doses, melted the bones of those who took it, so that finally they became boneless bags of skin within which bags they lived and thought but could not move, but simply lay where they were placed till someone placed them in a different shape.”

Heracles is too late to prevent the destruction of Mo, and so the kingdom is blown apart, its scattered fragments becoming Borneo, Easter Island, Australia and Hawaii. The rulers of Gobi are in no position to celebrate, however, as they have already turned into jellyfish-like creatures – forms which, thanks to the effects of the royal jelly, they shall now have for eternity. The story ends with the preserved bodies of Mo’s inhabitants being dug up in the present day; meanwhile, the narrator tells us, the gelatinous Emperor of Gobi is frozen somewhere in the Himalayas, and would live again were he only to be thawed out.

A Gernsback regular, David H. Keller often injected his stories with an element of what would now be termed body horror, showing a particular interest in the human body being twisted by science gone wrong. With “The Boneless Horror” he applies this motif to a fantasy setting – one that blessedly avoids the travelogue aspect that bogs down so many Gernsback-era depictions of secondary worlds.

“The Menace from Below” by Harl Vincent

On a spring morning in 1935, engineer Ward Platt reads a report in a newspaper declaring that a subway train carrying more than 500 passengers has mysteriously disappeared after leaving its station in Brooklyn. “No logical solution of the mystery has been advanced,” the report states, “though superstitious folk are hinting of ghostly visitations and all sorts of necromancy and witchcraft.” Ward and his partner Charles Frazee decide to investigate the mystery: “It seems to me,”

On a spring morning in 1935, engineer Ward Platt reads a report in a newspaper declaring that a subway train carrying more than 500 passengers has mysteriously disappeared after leaving its station in Brooklyn. “No logical solution of the mystery has been advanced,” the report states, “though superstitious folk are hinting of ghostly visitations and all sorts of necromancy and witchcraft.” Ward and his partner Charles Frazee decide to investigate the mystery: “It seems to me,”

says Charlie, “that we should have an Arthur Conan Doyle or a Houdini on this job rather than engineers and scientists and policemen.”

The story then cuts to another character, Tony Russell, who witnesses a suspicious occurrence through a window and goes to investigate. Inside, a young woman explains that her father has been murdered; Tony examines the body (which turns out to be that of Van Alstyne, a financier reportedly involved with shady dealings) but is unable to find the cause of death. Things get stranger when, after speaking with Van Alstyne’s daughter Margaret, Tony finds that the body has vanished – leaving only a pile of clothes.

Tony calls Ward and Charlie to discuss the mysterious goings-on (including Margaret’s report of having seen “nothing except a sudden deflation of the corpse-filled pyjamas which appeared to slump to the floor in a sort of a mist that left the clothing empty when it cleared”). As it happens, Tony’s job as president of a television company gives Ward an idea for investigating the missing train: “we might equip every train that enters the tunnel with one of the transmitters so that any further happening can be watched from a distance. Undoubtedly there will be repetitions of the incident.”

Sure enough, more vanishings occur. Next is a train that had Margaret on board; after that is a vehicle carrying Tony and Charlie, the disappearance of which is caught on television:

“Look!” he said, pointing a shaky finger to another of the screens. This one received the image from one of the permanent transmitters in the tunnel and it pictured the train itself from the rear. The violet haze had surrounded the metal-work of the cars and from every corner and angle there glowed sparkling pinpoints of light that sputtered and blinded the watchers like miniature explosions of flash powder. The tracks and bottom wall of the tube glowed brilliantly with the same eerie light and suddenly they vanished from view. The bottom seemed to have dropped from the tunnel, leaving a huge brightly lighted space beneath. But the train remained intact, seemingly poised in mid-air. Then, slowly, surely it was lowered into the great opening, apparently dropped by hydraulic jacks or other deliberate means. Before they could exclaim their astonishment the normal light of the tube was restored and to their amazed eyes the tracks and tunnel floor were in their original solid and uninterrupted condition.

Things grow stranger still when those who see the occurrence soon catch a glimpse of the culprit: Jeremiah Talbot, former Research Engineer of the Union Electric Company, who had been presumed dead for seven years – and he is accompanied by weird apelike creatures. As it happens, the passengers on the train find themselves in the hands of these same beings:

[A] strange breed of creatures, part human, part beast. Huge, barrel-like chests characterized these strange simian monsters who wore trousers like men but exposed the naked, hairy upper portions of their bodies without covering. Beady deep-set, black eyes peered out from beneath bushy brows in chalky-white faces of human mould. And, strangest of all, these faces were not malicious in repose. They were more like the hopelessly vacant visages of incurable idiots.

The captives are taken to meet Talbot, who reveals himself to be working in league with a notorious scientist named Ainsworth:

“When we left in my plane to escape the undesirable publicity given to our experiments in creative surgery, we had a definite plan in mind. But we had no idea that we were to become involved in so stupendous a thing as has developed. In the wilds of Labrador, Ainsworth had a secret laboratory which has since been discovered—denuded of its apparatus. We headed for this laboratory with the intention of marooning ourselves for many years to carry on the work of making humans from the lower animals. Wells’ Doctor Moreau in real life, you know. But the plane crashed before we reached our destination and we were forced to carry on in the direction of his laboratory on foot. Luckily we had escaped injury in the crash but the hardships of that attempt to reach the laboratory were terrible. After two days and nights we were overtaken by a blizzard which made continued progress impossible and we took refuge in a cave about a hundred and fifty miles northwest of Shipiskan Lake. This was the beginning of our good fortune.”

“But your plane was found completely consumed by fire and with the remains of human bones in the wreckage,” objected Tony.

“Yes. We returned later and set fire to it to throw any inquisitive searchers off the track. The bones were not human—though nearly human.”

Talbot and Ainsworth, it turns out, have an impressive set of inventions and discoveries to their names. For one, they found a vast network of underground caverns running beneath North America, inhabited by millions of ape-men whom the scientists have managed to place under control. The caverns are spacious enough for aeroplanes to be flown in – which comes in useful for Talbot and Ainsworth, as they have also invented atomic-powered aircraft.

Talbot and Ainsworth, it turns out, have an impressive set of inventions and discoveries to their names. For one, they found a vast network of underground caverns running beneath North America, inhabited by millions of ape-men whom the scientists have managed to place under control. The caverns are spacious enough for aeroplanes to be flown in – which comes in useful for Talbot and Ainsworth, as they have also invented atomic-powered aircraft.

This is just the beginning. The two villains have developed a means of transporting objects and people through the fourth dimension, hence their ability to make the trains vanish. At one point Talbot transports Charlie to the fourth dimension and back, revealing that he did the same to Margaret’s father – with the difference that the latter man spent more time in the extra dimension, an experience that was fatal.

Should they choose, they can also destroy their targets completely through atomic disintegration: “We have at our command an undreamed-of force that is released at the touch of a finger. Were it not under complete control – were it permitted to continue unchecked when once started – the annihilation of the world would result.” Ward and Charlie encounter Margaret while trapped underground, and the scientists take them on a tour of Subterrania:

When the car reached its destination they stepped into the open with expressions of astonishment that caused Talbot to smile and chuckle.

“Why—why—it’s beautiful,” gasped Margaret. They stood near the shore of a great body of water and, but for the different quality of light, it would have seemed that they were in the open air of their own world. Far overhead swept an arch of deep green that merged into nothingness in the distance where its color seemed to melt into a fathomless distance comparable to the heavens themselves. It seemed that there were five blue-white suns in this firmament—but no stars. Open-mouthed they stared at the wonders and beauties of Subterrania.

“The suns,” explained Talbot, “are great patches of phosphorescent materials imbedded in the arched roof of this huge cavern. The farthest is some six hundred miles from this point and it is the largest of all.”

Meanwhile, efforts to find the missing trains are still going ahead on the surface. The gloating Ainsworth shows the futile search on one of his screens:

“They’ll find no living beings when they break through into the cavern. All they’ll find is their silly subway trains—and eternity.”

“Good God!” cried Charlie, “you’ll not destroy them?”

Ainsworth looked the speaker over coolly. “And why not?” he asked.

“It’s murder—cold-blooded murder!” exclaimed Charlie.

“And what would they do with their rifles and machine guns if they reached us?” inquired the scientist.

Of the two villains, Ainsworth is the most brutal – after the attack on the rescue mission, he complains that only half of the victims were killed – but both men are involved in a fiendish masterplan that concerns the ape-men. These exist in two forms: one, according to Talbot, “are ape-men of the same general characteristics as the Pithecanthropus erectus of about a half million years B. C. But they had progressed to a civilization approximating that of the third interglacial period or about 75,000 years B. C.” (these are nicknamed Pithies by Ainsworth). The other race is the Grimaldi, a superior variety:

They had turned a corner and now advanced along a still wider thoroughfare where the huts were larger and more ornate. An air of greater dignity pervaded this street and they soon observed several of the Grimaldi lounging about in close proximity to their homes. These were similar to the higher type of ape-men who had assisted in their capture and, while of no greater size than the Pithies, they were still more erect and had much finer shaped heads and whiter skin. They were far less hairy and the sloping forehead and protruding chin was scarcely in evidence at all. Their eyes too held considerable more of intelligence.

The two villains, aided by cohorts on the upper world (“radicals who have been banded together during our several visits to the surface and they maintain our contact with the upper world”) scheme to create their own race of ape-men, superior still, by swapping the ape-men’s minds with those of the human captives:

Talbot raised his eyebrows at the tone of the inquirer’s voice. “Why,” he said coolly, “the main purpose is for the advancement of science. We are going to create a race of supermen, endow them with the best brains that can be obtained from the upper world and set them loose eventually to assist us in conquering and ruling the surface. It is a rotten civilization above, as you must all admit, and Ainsworth and I intend to correct its faults and make of it a worth-while aggregation of peoples.”

Margaret objects to this mind-swapping plan, prompting Talbot to reveal that – amongst his other sins – he is something of a classist:

“Oh, but I can’t bear to think of the poor humans who must give up their intelligence to these manufactured giants, and become morons like the one we saw in the second ward,” she begged.

“These people are nothing to you,” said Talbot, “They are not even your kind. Few of those who ride the subways are of the wealthy class who are your friends and associates. What difference does it make?”

Margaret was about to retort hotly and it was Tony’s turn to interfere. He nudged her with his elbow and she refrained from further objection.

But the plan goes awry when the two scientists lose control of their creations (“The strident voice and curses of Talbot and the screeching rage of Ainsworth told of their difficulty in regaining the mastery of which they had boasted. They had created Frankenstein monsters”). The rebellion of the hybrid supermen leads to a number of fatalities. Ainsworth perishes, followed by Margaret’s brother Bob (who had stowed away on board a plane); then Gorth, a noble ape-man who has befriended the protagonists, dies:

Gorth fell to his knees, then sat crouched against the wall rocking to and fro with arms about his stomach in a futile attempt to staunch the flow of blood and to relieve his pain.

“Yes,” he said, “Two beings. The real Gorth, who is a manufactured man—produced by those fiends, Ainsworth and Talbot, from a less fortunate creature. Then the other me, a poor captive from that great land which is now in the memory that never before existed. This other self has been so unhappy—there was a wife, two children—wonderful companions—in that far-away land where all was so bright. And now the—pain—the pain of longing that never ceases to tear at this great breast—the pain in the head that can not be relieved—the faces that come to torture in the darkness. I go—gladly—” Another victim of Talbot’s and Ainsworth’s ambition had paid the price and Tony stepped into his room and obtained a sheet with which he covered the form of Gorth where it had slipped to the floor in its final struggle.

Talbot, meanwhile, is fatally injured; but his better nature prevails and he helps Tony, Charlie and Margaret to escape to the surface, where they can be reunited with Ward in safety.

“The Menace from Below” by Harl Vincent embodies the extravagant directions in which magazine science fiction would be heading in the pulp era. It makes its debt to earlier authors clear (Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau is specifically mentioned in the dialogue) but where past generations would have contented themselves with one main SF concept per story, Harl Vincent ladles on one after the other: we have a subterranean world inhabited by ape-men and plesiosaurs; atomic-powered vehicles and weapons; fourth-dimensional travel; the mind-swapping process; and, just for seasoning, the use of television in mystery-solving, a concept that would have been very much at home in sister title Scientific Detective Monthly.

Some would say that Vincent has over-egged the pudding – but the fact is, this sort of pudding sold very well, and remains popular long after pulp magazines have given way to TV, comics and video games.

News and Reviews

A major addition to the magazine’s non-fiction material is the first half of a two-part essay, “The Problems of Space Flying” by Herman Potočnik (credited under the pseudonym of Captain Hermann Noordun, and translated from the German by Francis M. Currier). Excerpted from Potočnik’s book Das Problem der Befahrung des Weltraums, this marks new territory for Gernsback’s dedicated SF magazines: Amazing had dabbled in non-fiction, but nothing like this in terms of length or substance.

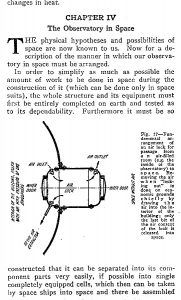

Citing the studies of Hermann Oberth the author discusses the effects of weightlessness on the human body, along with zero gravity’s hazards (“The cry of ‘Man overboard!’ on a space flyer has its meaning even in the absence of weight, though certainly in a different sense than on earth”) and everyday annoyances (“cloaks, dresses, aprons, and the like are useless as clothing”). Accompanying illustrations depict both the form that liquid would take in a weightless environment and the compressible vessels that might be used for storing drinks and other fluids in space. From here, the author makes a series of observations on the various hindrances and opportunities provided by space flight, from the lack of air to the newfound possibilities for astronomical observation:

Citing the studies of Hermann Oberth the author discusses the effects of weightlessness on the human body, along with zero gravity’s hazards (“The cry of ‘Man overboard!’ on a space flyer has its meaning even in the absence of weight, though certainly in a different sense than on earth”) and everyday annoyances (“cloaks, dresses, aprons, and the like are useless as clothing”). Accompanying illustrations depict both the form that liquid would take in a weightless environment and the compressible vessels that might be used for storing drinks and other fluids in space. From here, the author makes a series of observations on the various hindrances and opportunities provided by space flight, from the lack of air to the newfound possibilities for astronomical observation:

All these disadvantageous circumstances cease in the empty space of the universe; nothing now weakens the luminosity of the heavenly bodies, the fixed stars no longer twinkle, observations are not impeded by the blue of the sky. At any time, equally favorable and practically limitless possibilities are offered; for now that there is no optical hindrance, we could use telescopes of as great a size as we desire.

The article spends time discussing the matter of temperature, with descriptions of how objects could be warmed or cooled in space as mirrors and other devices are used to block or divert the rays of the sun. The final topic in this instalment is an outline of a hypothetical solar-powered space observatory, again with diagrams.

Outside of this essay, the issue has another round-up of news in the fields of astronomy and meteorology (“Dr. Ludwig [sic] Silberstein before the American Physical Society announced his measurement of the universe as having a radius of 32,500,000,000,000,000,000,000 miles”), aviation (“passengers in a plane 3,500 feet above Plainfield, N. J., carried on a telephone conversation with New York”), biology (“Dr. Oscar Riddle… believes that the use of specific hormones, in a pure form, will unquestionably cause the growth of human beings”), chemistry (“An alcohol produced from petroleum wastes which is without the usual ‘kick’ has been devised”), archaeology (“the age of man at a recent conference of the American Philosophical Society was placed at certainly several hundred thousand years and perhaps a million years”), geology (“The earth is reasonably safe from disastrous earthquakes for a while, is the conclusion given to the members of the Seismological Society”), medicine (“That the tendency toward an early decay of our teeth is becoming more and more serious is the conclusion of Professor Charles F. Boedker”) and broadcasting (“What has been predicted by science fiction writers, the receiving of our news by merely tuning in by radio, is about to become an actuality”), amongst other topics (“The home of the future will be windowless, says Albert Parsons Sachs… The Window, he contends, no longer serves a useful purpose and, in fact, it has many objectionable features”).

The section on physics news turns out to be the most interesting. As well as a report about audio-based warfare (“A ‘DEATH NOTE’ CREATED: A sound which striking the ears of one nearby kills him is the invention claimed by M. Marcigny of France”) we have details on Admiral Byrd’s use of electricity and radio during his Antarctic expedition and, keeping with the polar theme, a plan proposed by one Dr. H. Barjou to “produce power and heat by utilizing the difference in temperature between the arctic ice and the unfrozen water underneath… to make habitable these arctic waters”. Also included is a report on a “mechanical servant” designed by S. M. Kintner:

A new mechanical servant, or robot, the Telelux operated by light has been demonstrated by S M Kitner [sic] of the Westinghouse Electric Company. The robot is similar in general principle to the televox. In the case of the newer man he is operated by a light pistol whose beams are shot at him. A beam falls on a photo electric cell in him which selects three circuits to be operated. A second shot from the pistol operates one of the circuits and telelux opens or closes a desired circuit to put the lights on in a room or extinguishes them. The number of flashes of light on the selector cell determined which lights are to be turned out. A single flash on the operator cell caused the robot to obey the order. It is said to be possible to operate him from a distance of seventy five feet.

(Readers will remember the robot policeman used by Dr. Keller in the “Threat of the Robot” in the June issue of SCIENCE WONDER STORIES – Editor).

More information on Telelux can be found here. As with Televox, the device represents technology in the service of showmanship more than anything else, but its existence – and its coverage in this magazine – does reflect the rise of the robot as a key science fiction motif. Robots were not a particularly common theme throughout Gernsback’s run on Amazing Stories, but already they have become a recurring topic in Science Wonder Stories: note that Fletcher Pratt’s story in this issue even has a character using robots as a throwaway analogy.

Later in the magazine, we find another round of book reviews. The volumes covered this month are Problems of Instinct and Intelligence by Major R. W. Hingston (“A scientific textbook, and a thrilling story of the despised bugs that we crush beneath our feet”); The Strange Case of John R. Graham by Victor Kutchin (“an attempt to counteract Coueism and other spiritualistic creeds by exposing the basis of self-hypnotism”), The Witchery of Wasps by Edward G. Reinhard (“the author, after having spent many days in interested and intelligent study of their activities, has found them interesting creatures”) and Discovery of the Earth by George Parson (“an attempt to explain what must be a thrilling subject to everyone – how our solar system came into existence”).

The Reader Speaks

The readers’ contributions to the issue kick off with another round of entries in the “What Science Fiction Means to Me” guest editorial contest.

This month’s winner is by Tom Olog, and presented as a dialogue (“Written somewhat after the style of E. A. Poe”) between two characters: one the Scientific Supervisor of the Farther Top Side of Ultra-Universe; the other Master Mentality, Center of Ultra Universe. The former describes a trip through Earth’s history, during which he witnessed Columbus being (ahistorically) mocked for suggesting the Earth was round, an unnamed scientist for propounding an early theory of radio, and finally, some modern people being scoffed at for discussing travel through space and time. To rectify matters, the Master Mentality provides the traveller with an instrument that “can imprint on the minds of these people the value of foresight as to the aid of scientific progress” and “will become known on earth where it will be brought to the brains of people by their favorite recreation, which is fiction reading.” The instrument is, of course, science fiction.

The runners-up include James. P. Marshall (“Imagination! It is the key to happiness! Show me a man who feeds his spirit through imagination and anticipation and I will show you a happy man whose every minute is filled with pleasant activity”) and Michael Hnatke (“Science fiction is a conscious admittance of the propensity of our perceptions and is the effort of man to interpret the Supreme Order of Things. It is the struggle to reach beyond superstition, habit and standardization, to attain the goal that means unbiased truth and proper appreciation of God”).

Byron W. Dunlevey, another contender, prefigures the “fans are Slans” mentality of a later generation: “I have noticed that very few of my acquaintances can appreciate this kind of fiction because more than an average intelligence is required to grasp the salient factors of science fiction. Of course this tickles my inferiority complex and is very gratifying to my vanity, but I fear that this kind of fiction my never be read by the masses.”

Meanwhile, Louis H. Sther touches upon some similar topics as the winning entrant, albeit without constructing a work of fiction around his argument: “I feel there are a few million people, at least, who will reflect seriously on the pernicious injustice done to great men and great ideas of the past. What deaf ears and narrow minds listened to Copernicus, Newton, Galileo, Columbus! If, in the centuries past, there had been a medium to promulgate scientific literature and stimulate scientific interest there would are been a more ready acceptance of the ideas of our great men.”

The main letters section includes more general praise for Gernsback’s exploits (“I for one shall always be an ardent reader, no matter what the name is” says Bernard B. Melton). Jerome Levine speaks approvingly of the magazine’s non-fiction quotient, while G. B. Young requests that each issue un a biography of a noted scientist or inventor. Curtis Taylor requests stories by George Allan England and Garrett P. Serviss, but pours scorn on another author:

Leave out Stanton A Coblentz. He may be good-looking but his stories are not good. Take a story published in a magazine that came out in April. Men with large bodies and small heads, with large heads and small bodies, with human faces and wolf heads.

Alfred Greeny offers comments on the first issue’s stories. Quoting a headline from an unnamed newspaper reporting on “reds in new riot” in Berlin, he asks “Is the story, ‘The Reign of the Ray,’ going to be a true prophecy? According to the dates in the story the time is ripe for Socialistic rebellion and invasion.” Speaking of J. P. Marshall’s “Warriors of Space”, he questions “how the destroying ray that many authors have invented in many ways foes not destroy the ground directly beneath, thus creating a yawning gap wherever the ray happened to strike”. On Kennie McDowd’s “The Marble Virgin”, meanwhile, he declares that “the author has very little knowledge of anatomy”.

J. A. Ulan expresses technical concerns: “I don’t remember just now, but it seems as if the speed of the sun and earth didn’t check, according to the figures given in some of your stories.” (The letter even includes a diagram to back up the argument). Reader W.A.F. proves more open to scientific looseness: “Give us the impossible with the possible. Let the author be technically correct in things which are now known to science – but let us have imaginative tales which are not held down to the laws which are now known. In other words, let us have interesting fiction, not dry facts and figures!”

“I am only a high school girl in her senior year,” says Geraldine Compton, “but I don’t go in for a lot of foolishness that a lot of girls do. I would much rather sit at home with a good book than go out with a dozen boys.”

On the final page we find a letter from John W. Campbell – yes, the same John W. Campbell who would in 1937 become editor of rival magazine Astounding Stories. Campbell is remembered in large part for his dedication to hard science fiction, and this trait is on full view in his letter:

I just read the first issue of Science Wonder Stories, and I’m glad to see Mr. Gernsback is back in the science fiction business. I would like to suggest one thing—have one of your Physicists look over the “Science Questionnaire” before you let too many slips get by! In question two you ask what determines the speed of a body in space—and say there is no limit—or the author, referred to, does. The “Skylark of Space” got away with infinite speed by saying that he knew that a body really couldn’t go as fast as light—but in order to get away from Earth, to get out of the solar system he claimed a higher speed, and said Einstein’s mathematics were theory, and his speed was fact. For which bit of originality I admire him—but don’t pass the infinite speed idea out free! It really isn’t good—especially in the first issue! But to be serious, will you please tell me what your rules on stories are?

Read My Profile