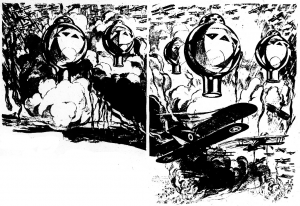

Two aviators lean out of an aircraft window at a strange sight. In front of the plane is a vast object, its shape suggesting a light bulb or a spherical bottle turned upside-down, with a large circular hole in the side. Even more bizarre is the vessel’s occupant: a puddle of yellow liquid sits on the ground, an arm reaching from the fluid into the round hole while a glum face gazes in the direction of the aeroplane.

Two aviators lean out of an aircraft window at a strange sight. In front of the plane is a vast object, its shape suggesting a light bulb or a spherical bottle turned upside-down, with a large circular hole in the side. Even more bizarre is the vessel’s occupant: a puddle of yellow liquid sits on the ground, an arm reaching from the fluid into the round hole while a glum face gazes in the direction of the aeroplane.

The February 1930 issue of Astounding Stories of Super-Science had hit the newsstands.

There is no editorial this month. Unlike rival Amazing Stories, Astounding makes no show of encouraging its readers to contemplate matters of science and technology. Instead, it heads straight into advertisements. An illustration of Fu Manchu leering at a girl in harem garb promotes an eleven-volume collection of books by Sax Rohmer: “Written with his uncanny knowledge of things Oriental… These are the sort of stories that President Wilson, Roosevelt and other great men read to help them relax”. Contemporary readers would also have been tempted by the Speedo automatic can-opening machine, two separate courses for those eager to work in the field of radio, and the African big game photographs of Forest and Stream magazine.

After these come the stories of super-science. Three authors from the previous issue – Captain S. P. Meek, Anthony Pelcher and Victor Rousseau – are joined by some newcomers to the publication, but old and new talent alike show a shared set of interests: their stories are characterised by bold heroes, scheming villains, and weird menaces that imperil the whole of planet Earth.

“Old Crompton’s Secret” by Harl Vincent

Old Crompton is an ill-tempered recluse who resides in a small Pennsylvania town. He frequently visits a local bookseller to purchase “translations of the writings of the alchemists and astrologers and philosophers of the dark ages”, leading to speculation amongst superstitious townspeople that he is in league with the Devil. Then wealthy college graduate Tom Forsythe moves in next door — much to Crompton’s displeasure.

Old Crompton is an ill-tempered recluse who resides in a small Pennsylvania town. He frequently visits a local bookseller to purchase “translations of the writings of the alchemists and astrologers and philosophers of the dark ages”, leading to speculation amongst superstitious townspeople that he is in league with the Devil. Then wealthy college graduate Tom Forsythe moves in next door — much to Crompton’s displeasure.

Tom turns out to be another recluse, spending his time conducting experiments in his personal laboratory. Crompton’s curiosity gets the better of him and he decides to visit his young neighbour, who is experimenting on animals: “I sometimes change them in physical form, sometimes cause them to become of huge size, sometimes produce pigmy offspring of normal animals.” Tom Forsythe’s ultimate aim, he explains, is to learn “the nature of the vital force — how to produce it. I shall prolong human life indefinitely; create artificial life. And the solution is more closely approached with each passing day.” The two become unlikely colleagues, with Crompton even helping to catch a three-foot-tall chicken that escaped from Tom’s lab.

Then, Tom calls on Crompton with the announcement that he has finally found the secret of immortality, and leads his neighbour to his laboratory:

In the exact center of the great single room there was what appeared to be a dissecting table, with a brilliant light overhead and with two of the odd glass bulbs at either end. It was to this table that Tom led the excited old man.

“This is my perfected apparatus,” said Tom proudly, “and by its use I intend to create a new race of supermen, men and women who will always retain, the vigor and strength of their youth and who cannot die excepting by actual destruction of their bodies, Under the influence of the rays all bodily ailments vanish as if by magic, and organic defects are quickly corrected. Watch this now.”

Tom demonstrates his apparatus by causing a rabbit to regrow an amputated limb; he explains that this is the result of the “vital rays” playing upon a certain gland. For a still greater performance, Tom then resurrects a suffocated guinea pig. “It is the secret of life and death!” he proclaims. “Aristocrats, plutocrats and beggars will beat a path to my door. But, never fear, I shall choose my subjects well. The name of Thomas Forsythe will yet be emblazoned in the Hall of Fame. I shall be master of the world!”

Old Crompton pleads to be rejuvenated with Tom’s invention. “What? You?” replies the young scientist. “Why, you old fossil! I told you I would choose my subjects carefully. They are to be people of standing and wealth, who can contribute to the fame and fortune of one Thomas Forsythe.”

The two come to blows over this disagreement, and the fight ends with Tom tripping and hitting his head on the floor. Leaving the inventor in a pool of blood, Crompton uses Tom’s device to restore his own youth, before destroying the apparatus and setting off to start a new life.

The story then jumps ahead twelve years, at which point a rejuvenated but conscience-stricken Crompton decides to hand himself in to the authorities for Tom’s murder. To his surprise, he is led to meet Tom Forsythe, who is alive and well: the fight in the laboratory had merely rendered him unconscious. Crompton’s rejuvenation abruptly wears off and his body deteriorates to its true age of one hundred years, but he cheerfully accepts this as the way things should be: “It is natural to age and to die. Immortality would make of us a people of restless misery.” Tom, who has long since abandoned his dreams of world domination, agrees with him.

The eccentric, reclusive inventor or researcher was already a stock character type in science fiction by this point, and “Old Crompton’s Secret” gives us two for the price of one. The story itself is a warmed-over selection of plot elements from H. G. Wells (or, going back even further, from Mary Shelley and Jonathan Swift); its most intriguing concept, that renewed youth is hampered by excess memories, is obscured by the abrupt jump forward in time towards the end. Still, Harl Vincent’s writing style is nice enough to paper over some of the cracks in the plot.

“Spawn of the Stars” by Charles Willard Diffin

Millionaire Cyrus R. Thurston goes on a flying trip over the Arizona desert during which he and his pilot Slim Riley notice a strange bulb-shaped vessel, with a still stranger occupant:

Millionaire Cyrus R. Thurston goes on a flying trip over the Arizona desert during which he and his pilot Slim Riley notice a strange bulb-shaped vessel, with a still stranger occupant:

It was some two hundred feet away. The lower part was lost in shadow, but its upper surfaces shone rounded and silvery like a giant bubble. It towered-‘, in the air, scores of feet above the chaparral beside it. There was a round spot of black on its side, which looked absurdly like a door….

“I saw something moving,” said Thurston slowly. “On the ground I saw…. Oh, good Lord, Slim, it isn’t real!”

Slim Riley made no reply. His eyes were riveted to an undulating, ghastly something that oozed and crawled in the pale light not far from the bulb. […] It was formless, shapeless, a heaving mound of nauseous matter. Yet even in its agonized writhing distortions they sensed the beating pulsations that marked it a living thing. There were unending ripplings crossing and recrosslng through the convolutions. To Thurston there was suddenly a sickening likeness: the thing was a brain from a gigantic skull–it was naked–was suffering…

Once this “raw, naked, thinking protoplasm” departs, the two men investigate the area and find the remains of a dead steer: “A body of raw bleeding meat. Half of it had been absorbed.” The next day, papers report sightings of the bulb-shaped vessel over America, Europe and China. This is just the beginning, and before long the invaders start laying waste to Earth. Thurston and Riley speak to the Secretary of War to help develop a plan of defence.

Right down to its alliterative title, “Spawn of the Stars” owes an obvious debt to The War of the Worlds. Shorter and considerably less subtle than H. G. Wells’ novel, it feels closer in spirit to the alien invasion films that would come into vogue in the 1950s. Instead of following an everyman character as Wells did, Charles Willard Diffin focuses on a joint military-scientific attempt to fight back against the aliens. The two main characters initially have different reactions to the alien visitors — Thurston muses about the possibility of communicating with the creatures, while Riley is simply eager to wipe them out — but such distinctions fade as the story progresses, the cast grows and the various characters begin blurring together.

Naturally, this pulpification of Wells’ story has plenty of blood and thunder. The aliens themselves are worthy successors to Wells’ Martian molluscs, being amorphous blobby creatures capable of growing eyes, limbs and other appendages when needed; in one scene Thurston is attacked by an arm that emerges from one of the creatures in a forerunner to Alien‘s facehugger attack (“It whipped about him, soft, sticky, viscid — utterly loathsome. He screamed once when it clung to his face, then tore savagely and in silence at the encircling folds”). The destruction caused by the alien invasion is conveyed through vivid descriptions of cities wiped out, ruins lined with blackened bodies, and holes left by bombing being converted into mass graves; one passage in particular manages to evoke nuclear bombings a decade-and-a-half before the fact (“And then — then the city was gone. A white cloud-bank billowed and mushroomed. Slowly, it seemed to the watcher — so slowly”).

The story has a more cerebral aspect as well, with plenty of musing about the scientific workings of the alien attack. Paying close attention to the alien vessels, the characters deduce that the machines use hydrogen both as a weapon and as a means of propulsion, via a technology unknown on Earth (“Our theory is this: the hydrogen atom has been split, resolved into components, not of electrons and the proton centers but held at some halfway point of decomposition”). The heroes are ultimately able to defeat the aliens, albeit only after a noble sacrifice.

“The Corpse on the Grating” by Hugh B. Cave

In this early story from an author whose career would last into the twenty-first century, Professor Daimler invites two of his friends — medical practitioner Dale and eccentric psychologist M. S. – to discuss his current line of research. He announces that he has been attempting to restore life to the body of a dead man, and claims that through the application of electric and acid heat he was able to temporarily animate a limb. Dale is skeptical, announcing that the process identified by the professor is merely galvanism.

In this early story from an author whose career would last into the twenty-first century, Professor Daimler invites two of his friends — medical practitioner Dale and eccentric psychologist M. S. – to discuss his current line of research. He announces that he has been attempting to restore life to the body of a dead man, and claims that through the application of electric and acid heat he was able to temporarily animate a limb. Dale is skeptical, announcing that the process identified by the professor is merely galvanism.

Returning home from their visit to the professor, Dale and M. S. walk past a warehouse. There, between the iron bars that guard one of the windows, is the corpse of the night-watchman:

His whole distorted body was forced against the barrier, like the form of a madman struggling to escape from his cage. His face—the image of it still haunts me whenever I see iron bars in the darkness of a passage—was the face of a man who has died from utter, stark horror. It was frozen in a silent shriek, of agony, staring out at me with fiendish maliciousness. Lips twisted apart. White teeth gleaming in the light. Bloody eyes, with a horrible glare of colorless pigment. And—dead.

M. S. claims to possess the ability to “read the thoughts of a dead man by the mental image that lay on that men’s brain” and, after examining the dead watchman, declares that he has found the source of the fright that caused the man’s death:

“I can see two things, Dale,” he said deliberately. “One of them is a dark, narrow room—a room piled with indistinct boxes and crates, and with an open door bearing the black number 4167. And in that open doorway, coming forward with slow steps—alive, with arms extended and a frightful face of passion—is a decayed human form. A corpse, Dale. A man who. has been, dead for many days, and is now—alive!”

Dale scoffs, prompting M. S. to physically attack him. Then, Dale agrees to a bet: to spend the night in the room where the watchmen saw his fatal sight. After a period of groping around the eerie surroundings of the darkened warehouse, he finds the designated room. There, he finds that the dead man had been reading “a book of horror, of fantasy. A collection of weird, terrifying, supernatural tales with grotesque illustrations in funereal black and white.” Looking closer, he finds a description in a story that matches exactly the account given by M. S. of the watchman’s final mental image. “Little wonder”, concludes Dale, “that the fellow on the grating below, after reading this orgy of horror, had suddenly gone mad with fright.”

He believes that he has solved the mystery, but Dale must still spend the rest of the night in the warehouse to meet the conditions of the bet. He starts reading the book to pass the time, beginning a story about a man imprisoned in a dark monastery. He is disturbed to find that the character’s situation – trapped in a dank, eerie chamber – mirrors his own. Then, just as the character in the book hears mysterious footsteps from outside, Dale begins hearing the same noise in the warehouse. Finally, Dale is confronted with the same terrible sight that he had read the hero of the story encounter a moment beforehand:

I screamed, screamed in utter horror at the thing I saw there. Dead? Good God, I do not know. It was a corpse, a dead human body, standing before me like some propped-up thing from the grave. A face half eaten away, terrible in its leering grin. Twisted mouth, with only a suggestion of lips, curled back over broken teeth. Hair—writhing, distorted—like a mass of moving, bloody coils. And its arms, ghastly white, bloodless, were extended toward me, with open, clutching hands. It was alive! Alive!

Dale flees. The following day, he discusses the events of the night with M. S., and the psychologist reveals that the warehouse contained a room in which Professor Daimler kept the body on which he had experimented. The experiment, then, had been a success – the professor’s only failure was in not waiting long enough to see the results.

“The Corpse on the Grating” is a curious story. As a mystery narrative it has an obvious flaw in that the professor’s experiment at the start renders the conclusion rather predictable. It also highlights some of the issues that arise when transplanting the stuff of Gothic horror to a science fictional setting: the ending, with the revelation that Professor Daimler has successfully developed a means of raising the dead, has tremendous implications that outweigh the main plot; had it been a supernatural ghost story, meanwhile, the dead man’s resurrection could have been confined to the sphere of knowledge forever outside of humanity’s reach. The plot detail that M. S. is somehow able to obtain the last image seen by the dead watchman – apparently inspired by the popular notion that a photograph of a murderer can be obtained from the victim’s eye – is another striking concept left largely unexplored.

But yet, the story still has interest, mainly due to the way in which it launches a thoughtful and analytical exploration of fear. This is most evident in the scene where Dale reads a horror story that mirrors the horror story in which he is a character, but there are other, more subtle examples. Consider the passage in which Dale, his imagination getting the better of him while he is trapped in the creepy warehouse, tries to comfort himself with memories of more physical horrors:

I had been through horror before. I had seen a man, supposedly dead on the operating table, jerk suddenly to his feet and scream. I had seen a young girl, not long before, awake in the midst of an operation, with the knife already in her frail body. Surely, after those definite horrors, no unknown danger would send me cringing back to the man who was waiting so bitterly for me to return.

“Creatures of the Light” by Sophie Wenzel Ellis

Scientist John Northwood finds himself being stared at by two men: one “singularly ugly and deformed”, the other classically handsome but filled with hatred: “If a figure in marble could display a fierce, unnatural passion, it would seem no more eldritch than the hate in the icy blue eyes.”

He later finds that the ugly man is Dr. Emil Mundson, a distinguished scientist, and remembers reading an article by Mundson on the future of human evolution:

Since the human body is chemical and electrical, increased knowledge of its powers and limitations will enable us to work with Nature in her sublime but infinitely slow processes of human evolution. We need not wait another fifty thousand years to be godlike creatures. Perhaps even now we may be standing at the beginning of the splendid bridge that will take us to that state of perfected evolution when we shall be Creatures who have reached the Light.

Northwood later gets into an argument with the handsome man from the café, who inexplicably vanishes into thin air. But it is Dr. Mundson who ultimately attracts Northwood’s attention (with the aid of a dropped wallet containing a photograph of a beautiful women) and the two meet up for a discussion, during which Mundson outlines the goal of his research:

Dr. Mundson’s intense eyes swept over Northwood’a tall, slim body.

“Ah, you’re a man!” he said softly. “You are what all men would be if we followed Nature’s plan that only the fit shall survive. But modern science is permitting the unfit to live and to mix their defective beings with the developing race!” His huge fist gesticulated madly.

“Fools! Fools! They need me and perfect men like you.”

“Why?”

“Because you can help me in my plan to populate the earth with a new race of godlike people. But don’t question me too closely now. Even if I should explain, you would call me insane. But watch: gradually I shall unfold the mystery before you, so that, you will believe.”

Mundson takes Northwood for a ride in a spherical, solar-powered aircraft. They stop off in the Antarctic, only for the craft to be stolen. Northwood suggests that the mysterious man from the cafe was responsible, prompting the doctor to reveal all. The mysterious man is Adam, the product of Mundson’s experiments with human evolution:

“What do you mean, Dr. Mundson: that this Adam has arrived at a point in evolution beyond this age?”

“Yes. Think of it! I visioned godlike creatures with the souls of gods. But, Heaven help us, man always will be man; always will lust for conquest. You and I, Northwood, and all others are barbarians to Adam. He and his kind will do what men always do to barbarians—conquer and kill.”

Just as the pair are contemplating a future of living in an igloo and feeding on penguins, Adam comes back for them. The pair travel with the superhuman, who has mastered the ability to turn invisible (“Not once, in that wild half-hour’s rush over the polar ice clouds, did they see Adam. They saw and heard only the weird signs of his presence: a puffing cigar hanging in midair, a glass of water swinging to unseen lips, a ghostly voice hurling threats and insults at them”) until they arrive at a curiously tropical stretch of the Antarctic, illuminated by an unusual light. “In your American slang,” exclaims Mundson, “it is canned sunshine containing an overabundance of certain rays, especially the Life Ray, which I have isolated.” One wonders if he corresponded with Tom Forsythe from “Old Crompton’s Secret”.

The area is New Eden, where Mundson created Adam, along with Adam’s ancestors. Northwood is introduced to Adam’s grandmother Lilith, who is physically a young woman: “She is of the first generation brought forth in the laboratory, and is no different from you or I, except that, at the age of five years, she is the ancestress of twenty generations.” Northwood also meets Athalia, the woman whose photograph was in Mundson’s wallet. Despite her great beauty, she is not one of the doctor’s creations; instead, she is an assistant he found in a New York sweatshop.

Northwood makes a move to win Athalia’s affections, only for Adam to appear and spirit her away. Untroubled by this development, the doctor continues to show Northwood all that he has accomplished by harnessing the Life Ray. Northwood comes to find this tampering with nature disturbing, and is particularly appalled to see babies that have been taken frm their mothers’ wombs and placed incide artificial incubators, where they undergo rapid development: “Lord! This is awful. No childhood; no mother to mould his mind! No parents to watch over him, to give him their tender care!” Dr. Mundson, however, protests that the children are a race of geniuses, with memories so photographic as to render written records unnecessary, and capable of creating works of great art from early ages.

Northwood then meets Eve, the woman created to be Adam’s bride before he spurned her for Athalia. She explains that her kind has the ability to enter the fourth dimension, hence Adam’s disappearances. With Eve’s help, Northwood locates Adam and Athalia, in the process learning that Adam is planning to destroy New Eden so thay only he and his captive survive: to do so, he has harnessed nature’s destructive properties just as Mundson harnessed its forces of life.

Eve gets hold of Adam’s death ray, and tests it on some unfortunate guinea pigs (“a cone of black mephitis shot forth, a loathsome, bituminous stream of putrefaction that reeked of the grave and the cesspool, of the utmost reaches of decay before the dust accepts the disintegrated atoms”). To Northwood’s dismay she announces that she plans to kill not only Adam but also Athalia, so that she can have Northwood to herself.

Eve successfully kills Adam, but trips and falls into the death ray, which blasts through the wall of the laboratory and into the valley outside. It devastates New Eden, reducing the inhabitants to dust and destroying the sunlight projector. Believing themselves to be the sole survivors, Northwood and Athalia embrace one another and prepare to die in an Antarctic blizzard — until Dr. Mundson arrives in the sun ship to rescue them.

“Creatures of the Light” is an early specimen of the sort of material likely to come to someone’s mind when they think of pulp science fiction. Its plot is built around elements borrowed from Mary Shelley, Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, given a collective update to fit contemporary technological advances, and mixed in with a formula of hero, villain and damsel in distress. Although not all of them are successfully integrated into the plot, the story offers a parade of provocative ideas: some are halfway plausible (solar-powered aircraft, artificial wombs) and others are more fantastical, but described with a fairy-tale conviction that lends them a certain credibility.

It is easy to criticise the story for its reliance on stock character types and its loose ends (the fact that Northwood has a fiancée back home named Mary Burns is completely forgotten by the end of the story) but it is just as easy to ignore these weaknesses and enjoy the ride.

“Into Space” by Sterner St. Paul

The second issue of Astounding includes two stories by Sterner St. Paul Meek – although in an apparent attempt to bulk out the magazine’s contributor list he is credited under to distinct names, first as Sterner St. Paul and then as Captain S. P. Meek. “Into Space” is told from the perspective of reporter Tom Faber, a former student of eccentric scientist. Tom pays a visit to the doctor’s ranch, which turns out to be guarded by a Native American who speaks Tonto-esque pidgin English (“No ketchum letter, no ketchum Doctor”) and eventually meets his scientist friend.

“I am crazy, crazy as a loon, which, by the way, is a highly sensible bird with a well balanced mentality”, declares the doctor. “There is no doubt that I am crazy, but my craziness is not of the usual type. Mine is the insanity of genius.”

Dr. Livermore goes on to claim “that magnetism, and gravity are one and the same, or, rather, that the two are separate, but similar manifestations of one force.” Tom is unconvinced and tries to argue, but the doctor stands firm on his theory. Furthermore, he declares that he has developed “an electrical method of neutralizing the gravity of a body while it is within the field of the earth, and also, by a light extension, a method of entirely reversing its polarity.” This has tremendous implications for aeronautics:

“Man alive,” he cried, “it means that the problem of aerial flight is entirely revolutionized, and that the era of interplanetary travel is at hand! Suppose that I construct an airship an then render it neutral to gravity. It would weigh nothing, absolutely nothing! The tiniest propeller would drive it at almost incalculable speed with a minimum consumption of power, for the only resistance to its motion would be the resistance of the air. If I were to reverse the polarity, it would be repelled from the earth with the same force with which it is now attracted, and it would rise with the same acceleration as a body falls toward the earth. It would travel to the moon in two hours and forty minutes.”

The doctor unveils his craft, which resembles a giant artillery shell, and flies off for the moon. But he never reaches his destination: Tom receives a radio broadcast from the Doctor revealing that he is “caught at the neutral point where the gravity of the earth and the moon are exactly equal” and will remain there until his oxygen supply runs out, his craft ending up as Earth’s new satellite.

“Into Space” draws a parallel between interplanetary travel and experiments with magnets. In doing so, it fits into the Gernsbackian tradition of using classroom science as the underpinning for a story of extravagant invention. It also shows the shortcomings of this approach. After hitting on the central concept of the story, Meek has trouble coming up with any idea of where to take it; with authors from H. G. Wells to E. E. Smith having already penned stories of inventors cobbling together interplanetary craft and flying off for adventures on alien worlds, Meek’s decision to have the inventor simply get lost in orbit seems a cop-out. That said, the story’s intriguing framing device, opening as it does with the mystery of enigmatic radio broadcasts seemingly connected to a new satellite in Earth’s, helps to make the most of the limited plot.

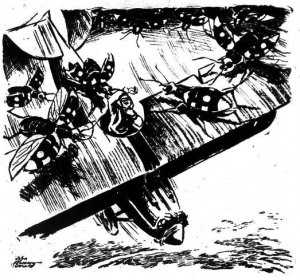

The Beetle Horde by Victor Rousseau (part 2 of 2)

The concluding instalment of Astounding’s first novel-length work begins with Tommy Travers, James Dodd and the cave-girl Haidia escaping from the underworld of Submundia. They are chased by giant beetles under the command of the mad scientist Bram, who remains as obsessed with paleontological disputes as before: “Now’s your last chance, Dodd. I’ll save you still if you’ll submit to me, if you’ll admit that there were fossil monotremes before the pleistocene epoch.”

They finally find an escape route, seeing the stars above through a hole in the cave ceiling, and clamber out. They emerge in the Australian outback, where a group of passing Aborigines provide them with food. The travellers tend to injuries sustained by Haidia, whom Dodd plans to marry (“I’ve always had the reputation of being a woman-hater, Tommy, but once I get that girl to civilization I’m going- to take her to the nearest Little Church Around the Corner in record time.”) But as they head for the nearest settlement, the explorers find that they are pursued: Bram and a fresh new brood of giant beetles have followed them onto the surface world.

At this point, the story switches from a lost-world saga to a War of the Worlds-esque narrative of widespread destruction at the hands of an inhuman menace. The action moves to a newsroom, where reports of the giant beetles are dismissed as an April Fools prank. But alas, the insect menace loose in Australia is no joke:

This was the swarm that was boring westward, and subsequently totally destroyed all living things in Kalgoorlie, Coolgardie, Perth, and all the coastal cities of Western Australia. Ships were found drifting in the Indian Ocean, totally destitute of crews and passengers; not even their skeletons were found, and it was estimated that the voracious monsters had carried them away bodily, devoured them in- the air, and dropped the remains into the water.

The giant beetles are joined by other species: “Soon it was known that prodigious creatures were following in the wake of the devastating horde. Mantissa, fifteen feet in height, winged things like pterodactyls, longer than bombing airplanes, followed, preying on the stragglers.” Even aircraft are brought down by the gigantic arthropods.

“I tell you I’m invincible,” screams Bram as he his horde lays waste to the world. “In three days Australia will be a ruin, a depopulated desert. In a week, all southern Asia, in three weeks Europe, in two months America.” The mad scientist’s involvement becomes common knowledge: “He was pictured as Anti-Christ, and the fulfilment of the prophecies of the Rock [sic] of Revelations.”

But then comes a flicker of hope. The beetles get so engorged that they no longer fit their shells, and are forced to moult leaving them vulnerable to counter-attack. While Dodd and Haidia get married, Tommy Travers leads a military endeavour against the insects: “National differences were forgotten, color and creed and race grew more tolerant of one another. A new day had dawned — the day of humanity’s true liberation.” This endeavour is a success, and the story ends with the two heroes stumbling across the fatally-injured Bram, ranting about monotremes to the very end.

“Mad Music” by Anthony Pelcher

A prestigious New York skyscraper suddenly collapses, killing ninety-seven people and leading to accusations of criminal negligence on the part of the company that built it. The firm turns to a bright but big-headed engineer named Teddy Jenks to look into the matter, hoping to find an external explanation for the disaster.

As he tries to come up with a solution, Jenks happens to make a bet with his colleague Linane:

“I’ve got a curious bet on, Mr. Linane. I am betting sound can travel 1 mile quicker than it travels a quarter of a mile.”

“What?” said Linane.

“I’m betting; fifty that sound can travel a mile quicker than it can travel a quarter of a mile.”

“Oh no—it can’t,” insisted Linane.

“Oh yes—it can!” decided Jenks.

“I’ll take some of that fool money myself,” said Linane.

“How much?” asked Jenks.

“As much as you want.”

“All right—five hundred dollars.”

“How you going to prove your contention?”

“By stop watches, and your men can hold the watches. We’ll bet that a pistol shot can be heard two miles away quicker than it can be heard a quarter of a mile away.”

“Sound travels about a fifth of a mile a second. The rate varies slightly according to temperature,” explained Linane. “At the freezing point the rate is 1,090 feet per second and increases a little over one foot for every degree Fahrenheit.”

“Hot or cold,” breezed Jenks, “I’m betting you five hundred dollars tint sound can travel two miles quicker than a quarter-mile.”

“You’re on, you damned idiot!” shouted the completely exasperated Linane.

Later, to set aside his troubles, Jenks attends a performance by a violinist billed as Munsterbergen, the Mad Musician; this turns out to be an immensely emotional piece of work:”The whole performance was as if someone had taken a heaven and plunged it into a hell). Afterwards, Jenks begins chatting with Elaine, the girl who sat next to him in the audience; coincidentally, she happens to be Linane’s daughter.

Jenks then conducts research into the Mad Musician, and finds that he has a fondness for shattering glasses with high notes. “If a madman takes delight in breaking glassware with a vibratory wave or vibration,” ponders the engineer, “how much more of a thrill would he get by crashing a mountain?”

Acting on their newfound suspicion, Jenks and Linane visit a four-room suite booked by the Mad Musician. They find that it contains a device consisting of a vast string and a mechanical bow, together making a sound too high to be audible — but capable of making the very building around it sway like a pendulum. Then the Mad Musician himself turns up, and after a struggle, accidentally stabs himself. The story ends with Jenks winning his earlier bet with Linane — and winning the heart of Linane’s daughter.

Having penned the previous issue’s “Invisible Death”, Anthony Pelcher comes up with another colourful inventor-villain who could easily have appeared in one of the superhero comics that became popular in the late 1930s. This is also a better-constructed story than his previous effort, although certain elements – such as the romance between Jenks and Elaine— seem tacked-on. The idea of adapting a glass-shattering note into a weapon of mass destruction is another example of familiar classroom science being inflated to make a viable premise for a pulp story.

“The Thief of Time” by Captain S. P. Meek

In his second story of the issue, Captain S. P. Meek returns to the Homes-and-Watson team of scientist Dr. Bird and secret service operative Carnes, characters introduced in the previous issue’s “The Cave of Horror”. This time, Bird and Carnes are called over to the First National Bank of Chicago to investigate the mysterious disappearance of a large number of notes. There are scant clues, save for a few reports of unusual sounds and sensations among the staff: “It was as if a person had passed suddenly before me so quickly that I couldn’t see him”, remarks one employee. “I seemed to feel that there was someone there, but I didn’t rightly see anything.”

In his second story of the issue, Captain S. P. Meek returns to the Homes-and-Watson team of scientist Dr. Bird and secret service operative Carnes, characters introduced in the previous issue’s “The Cave of Horror”. This time, Bird and Carnes are called over to the First National Bank of Chicago to investigate the mysterious disappearance of a large number of notes. There are scant clues, save for a few reports of unusual sounds and sensations among the staff: “It was as if a person had passed suddenly before me so quickly that I couldn’t see him”, remarks one employee. “I seemed to feel that there was someone there, but I didn’t rightly see anything.”

Sturtevant, a police detective also investigating the case, accuses the cashier who first noticed the money missing. But Dr. Bird has another theory.

He arranges to have a camera capable of capturing slow motion footage at 500,000 frames per second installed in the bank. When the invisible robber strikes again, the bank obtains footage of him – and he is identified as one Professor James Kirkwood.

Dr. Bird explains that the thieving professor’s former mentor was involved in artificially speeding up the growth of plants: “His studies of the effects of different colored lights, that is, rays of different wave-lengths, on the reactions which constitute growth in plants have had a great effect on pothouse forcing of plants and promise to revolutionize the truck gardening industry. He has speeded up the rate of growth to as high as ten times the normal rate in some cases.” The pair then applied their research to animals, successfully developing catalytic drugs that caused a puppy to “grow to maturity, pass through its entire normal life span, and die of old age in six months”.

Their next step was to adapt their drug so that it would not only work on humans, but could be regulated, allowing the user to speed up their metabolism over a specific period of time: “Suppose it were possible to increase your rate of metabolism and expenditure of energy, in other words, your rate of living, not six times, but thirty thousand times. In such a case you would live five minutes in one hundredth of a second.” And so, they developed a drug that granted superhuman speed, the user moving so fast as to be invisible to the naked eye. The two had previously sold their drug to athletes as a performance enhancer, unknowingly leaving a trail for Dr. Bird – himself a former athlete – to follow.

The idea of a drug that speeds up the taker until they become invisible to the human eye had already been explored by H. G. Wells in his 1901 story “The New Accelerator”, which was told from the perspective of characters affected by the drug. “The Thief of Time” is a less sophisticated treatment, as its use of the concept as fodder for a detective story means that it cannot explore the idea of superhuman speed until the very end. Still, it is a reasonably well-constructed mystery, and is also notable for further demonstrating Meek’s obvious interest in photography and filmmaking: as with “The Cave of Horror” Dr. Bird solves the mystery with the aid of a camera, the workings of which are described at length.

Read My Profile

Recent Comments