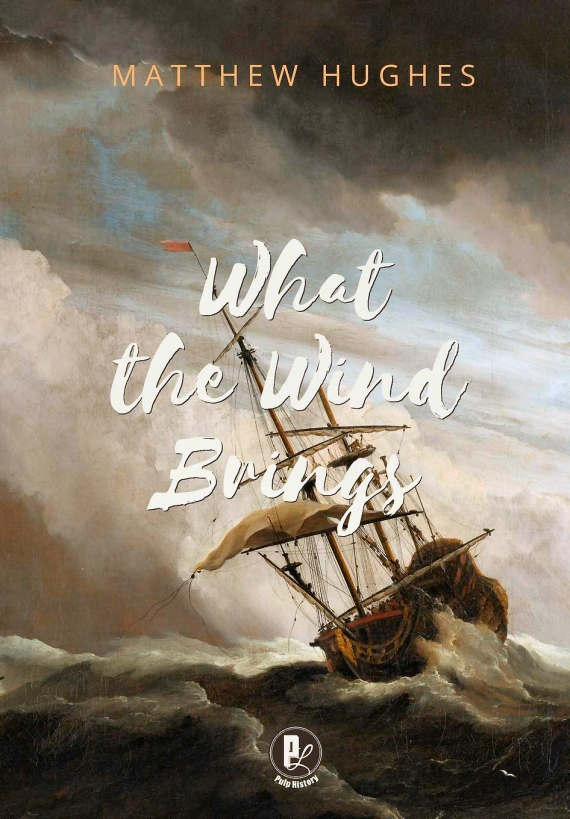

Canadian author Matthew Hughes, whose tales of Raffalon the thief have been very favorably received (by me, anyway), and who has written over 20 novels and short-story collections, has come out with a book my fellow Amazing Stories® columnist R. Graeme Cameron calls a “slipstream” novel. That is, it’s historical fiction with a twist—in this case, it’s history that occurred on a parallel timeline. Unlike the stories of Harry Turtledove, which can be called SF, this one has more fantasy elements than SFnal ones. In this novel, Hughes has proven that a small incident in a somewhat neglected part of the world can hold a reader’s interest just as well as an alternate version of a big historical battle like the American Civil War.

According to Hughes, in the 16th or 17th century (and a few Google shots would seem to bear him out), a group of real people who are referenced in this book, set in motion certain events that had a major effect on what is now present-day Ecuador (specifically, around the mouth of the Rio Esmeraldas (River of Emeralds), on the Northest coast of Ecuador. What is now historical fact is well-mixed with fiction, as Hughes—after a lot of research; one can tell—leads us through the events as they might have happened. (Because the natives told the Spanish that there were emerald mines up the river, the Spaniards—who were every bit as ambitious as empire builders as the British later came to be, and a lot more rapacious—named the river after these fictitious jewels. The natives were just trying to get the damned Spaniards to move on and stop enslaving them.)

Here are the facts as I understand them. A young man, called Alonso Illescas (captured as a very young child from the Mandinka tribe in Africa and raised by a noble Spanish family as more or less part of the family) has been sent to ferry a cargo of live pigs and other goods to Lima from the family plantation on the island of Hispaniola. Alonso has been raised the way a young Spanish cousin of the family might be, but is conscious of his own dark skin and the fact that he is not the family’s equal. Alonso has made a career out of “making himself useful” to ensure that he has a place, no matter how junior, in the family. He is also in charge of a coffle of African slaves, kept chained under lock and key, in the hold of the ship La Virgen.

But La Virgen is still days away from the port of Lima, and they’re running out of food and fresh water, so the captain makes a decision to put ashore for a brief time at the mouth of the river to get fresh water and perhaps scavenge some foodstuffs from a failed colony at the mouth. The African slaves are sent ashore under armed guard (arquebuses and cutlasses) to do the heavy work; Alonso goes with them as their supervisor. While they are all engaged in this work, a sudden storm comes up and, since La Virgen is too close to a reef near shore, the boats (minus the guards, Alonso and the slaves) are ordered to return to the ship immediately. A decision is made to tow the ship to safety. Alonso, the guards and slaves, are told to remain onshore until the danger has passed.

The winds are too sudden and too fierce, and the boats that are trying to tow the ship are upset and overturned, and the ship is dashed to the reef, and breaks up. During the brief, but furious, tropical storm and blinding rainfall, the African slaves fall upon the sailors and kill them. The pigs and all the sailors and Spanish or Portugese men and women on the ship are killed, and the slaves, led by the giant Anton, make their way into the jungle; Alonso manages to convince them that he can be useful to them and, partly because he, too, is dark-skinned, is taken along as an interpreter in case they need one. That much is, apparently, history.

What is not historical, but is made up from fragments of knowledge—the local Indios (indigenous peoples), called Nigua, are all gone and their language lost, but Hughes used words from their neighbouring Indios to fill in. Likewise, their culture has been lost through time, but again, Hughes has filled in. He has managed to bring to life not only the historical persons, but the fictional ones he has created, and the culture of not only the Nigua, but also the Spanish culture of the time. He’s done some meticulous research, and it shows. There are two characters he’s added: a hermaphroditic healer (not a functional hermaphrodite), and a monk of a Spanish Christian sect called the Trinitarians, who—practically alone of all the “Christians” in the book—is actually a practicing Christian who follows the teachings of Christ. (The other priests, mostly, are typical 16th-century Spaniards, more interested in power, wealth, and empire-building than following their putative god.) The hermaphrodite is called Expectation, and is able to do amazing things with her spiritual gifts, including spiritual as well as physical healing.

The way the slaves and the Nigua (and later neighbouring tribes) came together to form a culture where Africans and Ecuadorians—who, especially the bi-racial children, came to call themselves Zambos—formed an alliance that beat back the Spaniards with their higher technology and better arms and armour, and formed their own government (under the aegis and with the permission of Philip, King of Spain). All that is historical fact, though much of how it happened is fiction. It’s a very involving book, and a worthwhile read. I highly recommend it. (If I were to rate it, I’d give it five flibbets out of five: ¤¤¤¤¤!) Hughes himself has told me he considers it his masterwork, his magnum opus, and I think he’d have a hard time topping it. I also think it could make a pretty interesting movie, too.

**QUICK NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR, MATT HUGHES: One correction: the Trinitarian monk, Alejandro Espinosa, was a real person who joined the Zambos. His name was actually Alonso, too, but we had too many of them and so I changed it. There’s no evidence he was part of Cabello de Balboa’s mission, though. I just thought that made for good storytelling.

**Note on the cover shown in Figure 2: it’s a painting called De Windstoot, by Willem van de Velde the Younger from the Rijksmuseum, used with permission. If you like classic paintings, you can visit their website and download (for your own purposes) many wonderful pieces of art. This is an unsolicited plug; I was impressed with some of their collection.

**Other Stuff: This is the first of my last three columns for 2019; I intend to take the rest of the year (and possibly part of the new year) off as I’ve done for several years. I have two reviews to do: the Nov-Dec F&SF, and Chrome, by Lisa Mason. Look for a review early in 2020 of William Gibson’s Agency, the sequel to The Peripheral. I’m really looking forward to reviewing these three items! I hope you are too!

I really do welcome comments on my column, whether you comment here, or on Facebook. Every comment, good or bad, positive or negative, is read (Just keep it polite, okay?) and considered. Remember, my opinion is, as always, my own, and doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of Amazing Stories or its owner, editor, publisher or other columnists. See you next time!

Steve has been an active fan since the 1970s, when he founded the Palouse Empire Science Fiction Association and the more-or-less late MosCon in Pullman, WA and Moscow, ID, though he started reading SF/F in the early-to-mid 1950s, when he was just a sprat. He moved to Canada in 1985 and quickly became involved with Canadian cons, including ConText (’89 and ’81) and VCON. He’s published a couple of books and a number of short stories, and has collaborated with his two-time Aurora-winning wife Lynne Taylor Fahnestalk on a number of art projects. As of this writing he’s the proofreader for R. Graeme Cameron’s Polar Borealis and Polar Starlight publications. He’s been writing for Amazing Stories off and on since the early 1980s. His column can be found on Amazing Stories most Fridays.

Recent Comments