Can’t have your cake and eat it too.

That expression always puzzled me. Why have cake if you can’t eat it? Do they mean that stupid custom of freezing a piece of wedding cake so it can be eaten (yuck) on the 50th wedding anniversary (a probably deliberate suicidal pact between two people who’ve endured each others constant presence for fifty! years)?

Does it mean that once you’ve eaten your cake, you don’t “posess it” anymore so much as digest it?

Doesn’t matter. It’s just the lead in to a post and an attempt to explain that I, your publisher, often have contradictory feelings about things, especially history. Such as the history of the “science fiction magazine”.

History is nasty, for anyone wanting to stake a claim, plant a flag, offer up definitive proof because history is anything but definitive. Did World War I start because of an assassination? Yes…and No. Did Edison really invent the light bulb? No…and Yes. Was the first science fiction magazine Amazing Stories? YES. Did Hugo Gernsback define and create the genre and its fannish culture? YES and YES.

Except (and you’re not really supposed to pay attention to this part), stuff happened before those things happened and, if we are being “honest to a ‘T'” (why to a ‘T’? If you wanted to suggest complete honesty, wouldn’t you say “Honest to the Z”? Never mind. Spend time on that later and elsewhere), we are forced to recognize that some things occurred prior to Gernsback’s ABSOLUTELY UNIQUE CONTRIBUTIONS that contributed to his contributions.

First, fantabulous stories that contained elements that would later come to be associated with the science fiction genre were included in stories going all the way back to the earliest known story – the Tales of Gilgamesh. This is often pointed out by literary historians as ‘proof’ that science fiction has always been with us. Except those historians seem to have forgotten that “science”, as a thing, hasn’t existed but for the past couple of hundred years. Which mitigates against the existence of any ‘science’ or ‘scientific extrapolation’ as elements of those stories, placing them firmly in the realm of fantasy.

All of these tales – the ones by Lucien, deBergerac, Moore, etc., pretty much any fantastical fiction written prior to the existence of “science” – oh, about the middle 1500s to middle 1600s – can’t be considered anything but fantasy. The most learned men (and women) of that era were still arguing over how to conduct observations, what a theory was, how to logically perform inductive reasoning and, let’s face it: the extrapolative value of flying Geese to the Moone is nil.

I’ve often cautioned critics to evaluate whether or not the science and extrapolation in a work of SF was valid at the time the story was written, claiming that if it was, then the work remains a legitimate work of SF, whether its background or predictions remain valid or not in contemporary times. Capturing a gaggle of geese and harnessing them for a flight to the moon was demonstrably non-viable in deBergerac’s day, even if one assumes that an atmosphere extends from the Earth to its satellite.

Which brings us to Mary Shelley, the 1700s, galvanism and the first recognizably scientifically-based story that can almost be considered science fiction. Mary had been privy to demonstrations of the newly patented science of galvanics – applying electrical currents to living systems, and/or the creation of electrical currents by chemical means.

Galvani’s theories proved to be wrong, but for a while, the idea that “life” might be electrically based, was all the rage in Europe. (Indeed, in proving those theories wrong, Volta created the first chemical battery, neatly demonstrating that the scientific method itself was viable.) Ms. Shelley performed what we believe to be the very first formal presentation of literary scientific extrapolation: what if Galvanism could do more than just cause dead tissue to mimic the actions of a living system? What if restoring electrical current to a dead organism could restore it to life?

But then she fell down on the job, using the initial speculation as a ploy to get to her real focus – what happens when men can play God? That, by itself, is not an extrapolation, it’s a moral question. Had she been writing science fiction (rather than a gothic horror tale) the result might have more closely resembled Huxley’s Brave New World; a place where the galvanized were ubiquitous, not accorded equal status (thereby becoming the “other”) and it is for that and other reasons (such as a lack of a definition of the genre her novel would come to represent as the seminal precursor) that Frankenstein and its near descendants (Wells, Bellamy, Verne, etc) remain defined as “proto science fiction”; they’ve got most of the trappings, they’re close enough to be shelved in the same section, but they weren’t intentionally created within the framework of a formalized genre and therefore, like Moses, they are not allowed into the promised land. But they can sit on the border and look in. And we recognize that had it not been for them, we would not be where we are today.

Which is all by way of getting to the present, which, in this case, is sometime around 1912 or thereabouts. Wells had been writing scientific romances for about a decade at this point; ERB was making his debut; magazine publishers were discovering the financial benefits of a middle class that had both more money and time at their disposal and several near-science fictional efforts at prognostication were fresh in people’s minds; Forster’s The Machine Stops was fresh in people’s minds and Bellamy’s Looking Backward was not yet long in the tooth.

A young immigre was making his way in the world, selling radio parts and extolling the virtues of science and technology by dint of establishing a publishing empire and saw a way – through literature – to marry his desire to make everyone a research scientist with his interest in works of scientifiction, a genre he would go on to formally define within a few short years.

He had an idea – that by publishing stories that presented science and technology in a positive manner, ones that speculated on future developments and did so in an entertaining fashion, he might do for ALL of science and technology what he had done for radioscience – popularize it, make it familiar, make it approachable and understandable.

And he experimented with this idea through the teens and early 20s of the last century by writing some himself and by engaging with bibliographers who were beginning to collect and catalog such tales, using them to identify stories suitable for publication and then presenting them in one of his many magazines.

We refer, of course, to Hugo Gernsback.

Hugo was not alone in recognizing the appeal of fantastical tales in far-off places; All Story and Argosy magazines were sorta-kinda publishing such fare on a regular basis (Burroughs, Leinster) as were other rags, but everyone, it seems, was lumpinig such fancies together with everything else, and, lets face it, given the level of global ignorance in the early 1900s, there were a lot of places on the planet that were as unknown and foreign as the surface of Mars, not to mention daily eruptions of new technologies that made it seem as if anything – anything – remained within the realm of possibility: a world inside the center of the Earth? creatures living in clouds? a special light that could let you see inside of things? An elixir that could turn one invisible? Heck, half the people in the world back then were probably willing to admit that they had actually experienced such things!

We’re talking about an era of rapid change, and not just change in one limited area, but change across the board; transportation, communications, medicine, textiles, building materials, the adaptation of electricity to nearly everything, political thought, diet, entertainment – everything.

It should therefore come as no surprise that magazines would begin to deal in features and promotional gimmicks that played off of the wonderment of the age.

What was going to happen next? was, we can assume, a major topic of casual conversation and thought: now that electric street lights were beginning to light up cities across the globe – might it not be possible to light an entire city with one giant lightbulb placed above it? Now that huge airships were crossing oceans in record time – might it not be possible for them to get even larger? Since one could now talk to someone else via electricity – might it not be possible to see them as well?

I’m pretty sure that the expression “what will they think of next?” finds its origins in this era.

Mavens of entertainment (pulp magazine publishers among them) are ever keen to jump on a trend; speculation about the wonders of the day and where things were headed was one such, and so it was that the very first magazine identified as possibly the first science fiction magazine, came to be with the the publication of a special Twentieth Century Number of The Overland Monthly magazine in June of 1890.

Mavens of entertainment (pulp magazine publishers among them) are ever keen to jump on a trend; speculation about the wonders of the day and where things were headed was one such, and so it was that the very first magazine identified as possibly the first science fiction magazine, came to be with the the publication of a special Twentieth Century Number of The Overland Monthly magazine in June of 1890.

Inspired by Bellamy’s Looking Backward, the issue featured a number of proto-science fiction stories and speculation about what was to come with the turn of the century. Below, the table of contents. More on this effort can be found at the SF Encyclopedia.

And you can read the entire year’s worth of issues on the Internet Archive.

This was a one-off, obviously an attempt to play off of Bellamy’s book.

But there would be more, though it would be from across the pond.

Next up (so long as we stick to English language efforts – there were nascent efforts in Germany, Russia and Sweden during this time), we arrive at Pears Annual Christmas 1919 special.

Pears was a soap company that apparently used a magazine to help promote their offerings. In 1919 – just a handful of months after the conclusion of the Great War – they issued a prognosticatory look at what the world would look like 50 years hence.

None of them predicted the Moon landing.

And the exercise was not repeated in subsequent years by Pears Annual, leaving us to class it as a one-off – again, probably inspired by the zeitgeist of the time and seen as acceptable fodder for attracting magazine buyers; following WWI it was probably a good idea to present content that took a positive – if humorous – view of the future.

Sadly, the only copies of this known are in private collections or library collections and it was not possible to obtain an image; however, by way of substitution and brief mention: one of the features was a series of illustrations by W. Heath Robinson – the British Rube Goldberg – depicting an imagined 1969; he did extensive illustrations during the war, often featuring absurd weapons. Here’s one. Giant springs are used to propel soldiers, equipped with hip-mounted wings, across the Rhine:

Up till now (again, excepting the non-English efforts), “science fiction” as it was not yet known, was presented as an exercise in peering into the future, strictly for entertainment purposes, whimsy if you will. While doing so, though they included two of the elements that would comprise Gernsback’s forthcoming definition, they still lacked a third leg; they weren’t based on real science. Put another way, there was little to no context, no formal “world-building” going on, any more than can be found in say, Rip Van Winkle. Connecting the dots between ‘then’ and ‘now’ was not a necessary component for imaging what (their) future might hold, it was enough to simply imagine “what they will think of next”.

In 1911, Gernsback wrote the infamous Ralph 124C41+ (A Romance of the Year 2660) and serialized it in his magazine Modern Electrics. It was his first experiment and attempt to put into fiction the ideas and concepts that were coming to represent a new genre. (Interesting to note that the first issue of Modern Electrics that featured Ralph was the April 1911 issue. Did this influence the release date of the first issue of Amazing Stories?) Ralph was meant to exemplify the elements that made up his newly defined genre of “scientifiction”; while it did achieve that purpose, it is sadly lacking in the “entertainment” department and could serve as an example of what info dumps are and how not to use them, not to mention a good source for examples of “telling, not showing”.

In 1911, Gernsback wrote the infamous Ralph 124C41+ (A Romance of the Year 2660) and serialized it in his magazine Modern Electrics. It was his first experiment and attempt to put into fiction the ideas and concepts that were coming to represent a new genre. (Interesting to note that the first issue of Modern Electrics that featured Ralph was the April 1911 issue. Did this influence the release date of the first issue of Amazing Stories?) Ralph was meant to exemplify the elements that made up his newly defined genre of “scientifiction”; while it did achieve that purpose, it is sadly lacking in the “entertainment” department and could serve as an example of what info dumps are and how not to use them, not to mention a good source for examples of “telling, not showing”.

Regarldess, it was well received enough to suggest to Hugo that he was on to something.

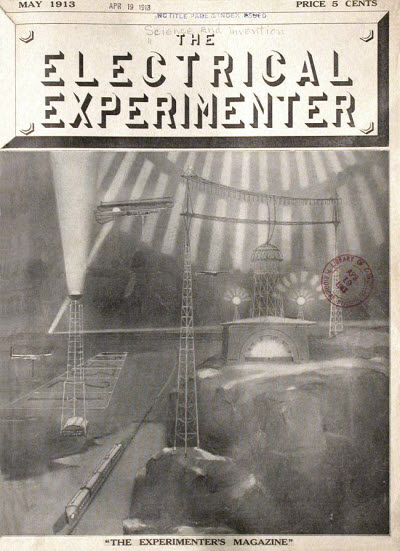

In 1913 Gernsback launched the Electrical Experimenter, a monthly that expanded his previous offerings that concentrated on radio science to include a wider remit of science and technology;

In 1913 Gernsback launched the Electrical Experimenter, a monthly that expanded his previous offerings that concentrated on radio science to include a wider remit of science and technology;

and in 1915, he wrote and began to serialize the New Adventures of Baron Munchhausen, as a way of illustrating the kind of stories he would eventually identify as science fiction.

and in 1915, he wrote and began to serialize the New Adventures of Baron Munchhausen, as a way of illustrating the kind of stories he would eventually identify as science fiction.

If the letter columns are to be believed, Munchausen was much more popular than Ralph, providing further proof that Gernsback was on the right track; he would continue to sprinkle stories of the kind he was looking for throughout the issues of the Electrical Experimenter, culminating with the special Scientific Fiction Number of 1923, but

we’re getting ahead of ourselves, because, in 1919, Street and Smith – the very same publishing house that would bring Astounding Stories of Super Science to the stands eleven years later – would publish The Thrill Book.

The Thrill Book was an attempt to publish “different” stories, interesting and entertaining, yet unclassifiable stories. The magazine featured authors who would come to be associated with both science fiction and weird horror in later years – Leinster, Quinn, Bedford-Jones, and much of the content would be classified as science fiction or fantasy these days (if a bit dated at this point), but, in addition to identifying itself as featuring “different” stories, it clearly did not identifiy itself as featuring “science fiction”, nor even “scientific fiction” or “scientifiction”. Instead of being devoted to exemplifying and establishing a specific genre, it was meant to serve as a catch-all. Owing to this lack of focus, it wasn’t specializing its focus on a specific genre and is therefore considered to be a precursor to what was to come in just a few year’s time. In 1923, a magazine unlike any other appeared on the stands – Weird Tales.

The Thrill Book was an attempt to publish “different” stories, interesting and entertaining, yet unclassifiable stories. The magazine featured authors who would come to be associated with both science fiction and weird horror in later years – Leinster, Quinn, Bedford-Jones, and much of the content would be classified as science fiction or fantasy these days (if a bit dated at this point), but, in addition to identifying itself as featuring “different” stories, it clearly did not identifiy itself as featuring “science fiction”, nor even “scientific fiction” or “scientifiction”. Instead of being devoted to exemplifying and establishing a specific genre, it was meant to serve as a catch-all. Owing to this lack of focus, it wasn’t specializing its focus on a specific genre and is therefore considered to be a precursor to what was to come in just a few year’s time. In 1923, a magazine unlike any other appeared on the stands – Weird Tales.

The Thrill Book wasn’t the only magazine dogging Hugo’s trail.

The Thrill Book wasn’t the only magazine dogging Hugo’s trail.

Weird Tales, the ‘Unique Magazine’, hit the stands in February of 1923 with a cover date of March. It would continue in publication, with fits and starts and gaps, until the present day. Although the magazine published some works that would come to be identified as “science fiction”, it’s primary focus was on stories centered on the fantastical and the macabre; Conan was featured, the Cthulhu mythos was featured, stories about detectives investigating the paranormal…despite the presence of some SF, it has rightly come to be seen not as a precursor science fiction magazine but as the UR of the weird fiction realm.

Shortly thereafter, a special All Scientific Fiction issue of the Electrical Experimenter was issued by Gernsback. He’d been regularly publishing proto SF in the magazine up to that point (he’d changed the name of the Electrical Experimenter to Science and Invention in 1920); could this have been a response to Weird Tales? Who knows, though, after reading histories and biographies related to Gernsback and his magazines, it is pretty clear that he had some proprietary interest in what was gelling as a specific genre in his mind.

Shortly thereafter, a special All Scientific Fiction issue of the Electrical Experimenter was issued by Gernsback. He’d been regularly publishing proto SF in the magazine up to that point (he’d changed the name of the Electrical Experimenter to Science and Invention in 1920); could this have been a response to Weird Tales? Who knows, though, after reading histories and biographies related to Gernsback and his magazines, it is pretty clear that he had some proprietary interest in what was gelling as a specific genre in his mind.

The contents of that issue included Wertenbackers’ The Man from the Atom, a story reprinted in the very first issue of Amazing, and a story you can read right here.

Gernsback must have been feeling some pressure to establish a magazine devoted entirely to his baby as, just a few months after the all scientific fiction issue, he sent a letter to 25,000 subscribers (subscribers to a related magazine, Practical Electrics, inquiring whether they would be interested in a magazine devoted entirely to scientific fiction.

The response was lackluster and the idea was held in abeyance for another two years. Until March 10, 1926 when the very first issue of the very first magazine devoted entirely to a newly defined liteary genre, was introduced to the newsstands, where it would go on to requried additional printings in order to meet demand, and, a bit later, it would go on to be instrumental in the formation of Science Fiction Fandom. But that, my friends, will have to be reserved for different lenthy article.

Images sourced from Wikipedia, the Internet Archive and Philsp.com (a wonderful visual database of magazines)

Steve Davidson is the publisher of Amazing Stories.

Steve has been a passionate fan of science fiction since the mid-60s, before he even knew what it was called.