Many times a story isn’t so much about what happens at the ending, but rather the journey taken to get there. In fact the “road trip” movies of the 70’s and 80’s are a genre unto themselves. Move this genre to science fiction and you have something that remains eminently relate-able to anyone who has ever had to cram five friends into a four-seater and make the run from Tijuana to San Francisco in eight hours OR ELSE*.

Allow me to to step up onto my soapbox for a moment to point out that a win-condition in games is a wildly varied thing. When you try to describe a sandbox game like Minecraft to someone, one of their first questions is, “Okay, so how do you WIN?” Because everyone *presumes* that game==WINNING. In the same way that enjoyment of a novel is not really about the ending (you can have a great book with a perfectly unsatisfying ending and people will still love it) games are much more about the overall experience of play as they are about the win.

In games, the mechanics are the key, making sure that the interaction between player and game is a satisfactory (not even enjoyable, really) experience. To that end, when we design a science-fictional videogame, the satisfaction of a science fiction audience is what we have in mind. Not insofar as delivering the perfect fan experience, but rather delivering the same feeling of satisfaction a viewer/reader gets when when the hyperdrive finally kicks in, or when the final puzzle piece of a character’s backstory klunks into place, revealing the plan all along. Science fiction audiences tend to be a little more patient, a little more drawn into the larger “what if” of a scenario and so those games tend to be a little richer, a littler slower when delivering mechanics to evoke that experience.

The Journey’s the Point

For this weeks article, I’m looking at science -fictional elements in games where the journey itself is the important thing. In a more traditional media form this shows up in places like television’s Battlestar Galactica , or novels like Neil Gaiman’s “American Gods” and Stephen King’s “The Stand“. In games, however, journeys tend to appear most often in the independent or “experimental” games categories, often because the overall experience they deliver overrides the game mechanics you might otherwise use to classify the game.

By their very nature, journey stories tend to be lush. The level of detail in the worlds is heightened, the incidents and activities that the characters engage in are more devoted to character building and growth than plot advancement. They are more evenly paced and slower overall, allowing for moments of player introspection and world examination that make them perfect for the more existential “what-ifs” of science fiction. There is often no end-goal in mind other than “arrive at Point B” and as such, the expectations of the audience are different than they might be with an action-narrative or a puzzle.

So with this in mind, I wanted to take a look at how science-fiction shows up in games that follow this more “experimental” format. Game genres are identified by the primary mechanic the player uses to engage with the game. We have the “First Person Shooter” or FPS, the “Real Time Strategy” or RTS and so on and so forth. In a meta-game fashion, you can slot some of these AAA style games into the idea of a journey (Horizon Zero Dawn, after all, is all about Aloy’s journey from outcast savior of the world and there is a lot of road-travel in between those two points). In a real-playable terms fashion, these games often end up in the “experimental” game category, in large part because that’s where players looking for innovative experiences start looking for them.

Experimental Games

Experimental games in general are where a lot of concepts or mechanics can be tried out, especially if they are riskier. Experimental games promise that, above all else, you’re going to be asked to take a leap of faith, to trust that the designers and engineers are going to deliver you an experience that is worth your time, even if you have never seen the mechanics anywhere else. It’s a bit like ordering off the “degustation menu” at a high-end restaurant. You don’t know what you’re going to get up front, but you know it’s going to be very good.

Key Concept: Cantankerous vehicle

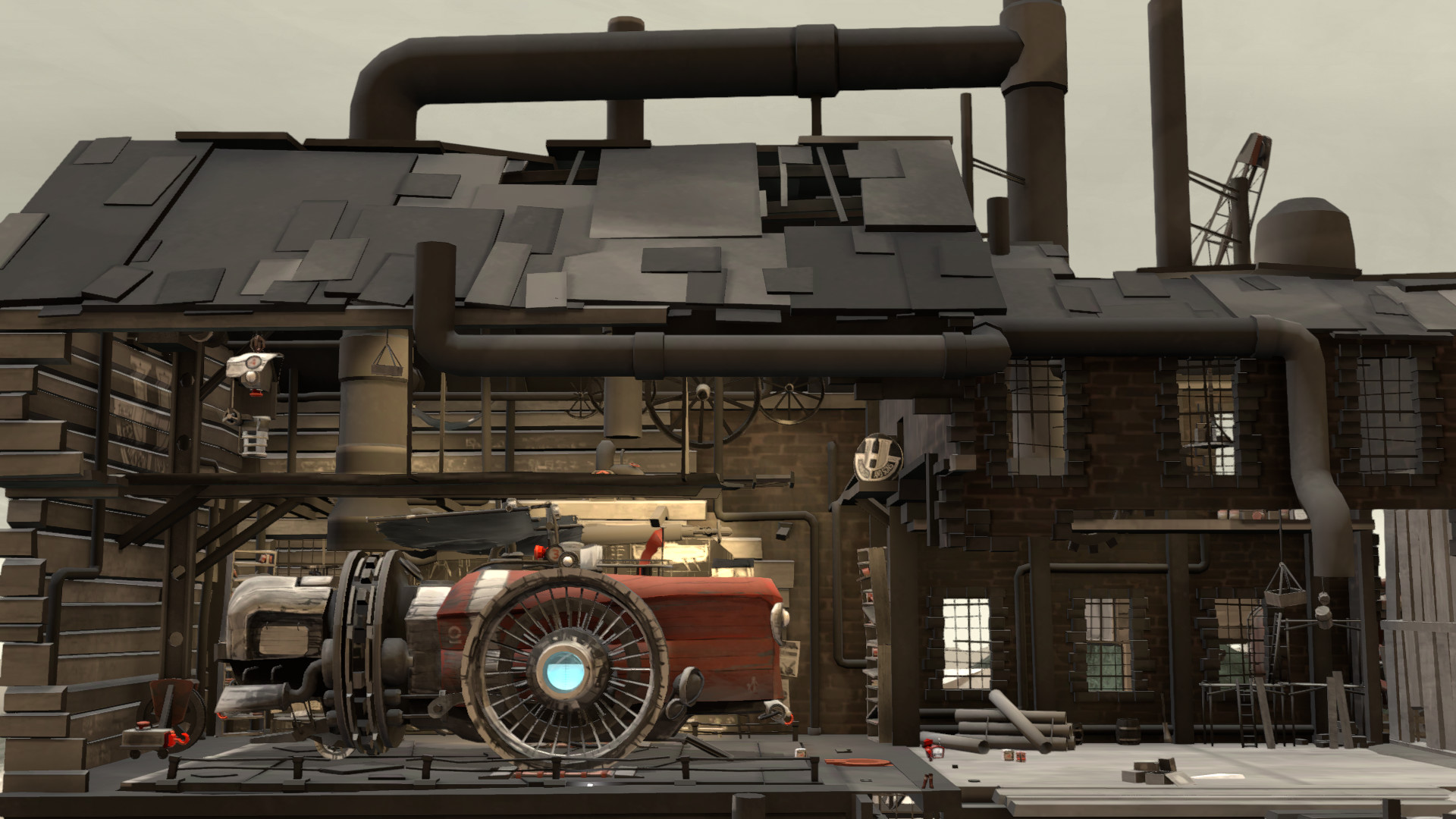

“Far: Lone Sails” is an independent game developed by Okomotive, originally for the PC, but it has since made an appearance on PS4 and is headed to other platforms as well. The game takes advantage of one of the classic elements of sci-fi travel stories, the vehicle with a personality of it’s own. Science fiction is full of vehicles that have some level of sentience. In some cases they are fully aware, whole characters, in others they display moods and opinions through their own form of mechanical pantomime. Sometimes the protagonist alone drives the impression, treating and speaking to the vehicle like a friend or lover. But rather than the vehicle serving as a plot device (a-la the Tardis from Dr Who) or a fully realized character (such as The Ship Who Sang) the care, feeding and cajoling of your sail-ship is an integral part of the gameplay mechanics. Your goal, after all, is to travel the dried-up seabed left after a civilization’s collapse.

By taking this science fictional element and meshing it with a maintenance mechanic, the game has tied your survival, and ultimate success, directly to the ongoing health (and presumably happiness) of your cantankerous machine.

Key Concept: The Migration

The idea of the journey as a means to saving one’s village, or culture or civilization, crops up again and again in science fiction. It might be a simple annual migration, as we saw in Homeward (Star Trek: TNG) or it might be a larger, more complicated trek and we are seeing just a small piece in a thousand year journey, as reflected in a work like Heinlein’s “Orphans of the Sky”. One of the best examples of this kind of story in videogames is Journey. Very experimental in terms of not only it’s gameplay mechanics but that it was developed by indie studio ThatGameCompany and published by one of the big AAA publishers (Sony). Much like Ecco the Dolphin did years before, Journey drove home the idea that the experience of playing the game, the journey itself was the best reason to play.

One of the most interesting aspects of this game is that, after a certain point, it becomes a multiplayer experience. There’s no matchmaking, no signups or character creation tools. Even more interesting, there is no method of communication, outside of pantomime and the ability to emit a PING. As you work your way through this alien world, you simply… encounter other players, all traveling the same kind of journey as you, all with similar goals as you.

But, you may find yourself asking, how to you collaborate without words? How do you compete without a way to keep score?

And this, interestingly enough, is one of the key elements what makes the experience of playing Journey so unique. It’s rather like being a stranded space-farer on an alien planet. You may know what you want, but the outcome when you encounter someone else is entirely dependent on you sharing similar goals. You can’t make deals, you cannot rely on conversation or cajoling. You have no common language to speak of. All you can do is PING. It brings to mind films like The Arrival, where communication is the focus, but is frustratingly elusive. But, at the end of the day, you all have the same goal, to finish getting from Point A to Point B and without a good reason to get there first (i.e. “winning”) it seems that many strangers are much more willing to work together towards that common goal.

Wrap Up

In purely narrative forms, the elements of the journey are often reflected in the development of the characters themselves, serving as a way to reinforce and reflect. For videogames, this often puts these kinds of stories into the Experimental Games category, not because they are less worthwhile than, say a FPS, but rather because when gamers are looking for an experience that is more introspective, that shows them something truly new and weird, that’s where they are going to start looking.