I took this hummingbird picture (Figure 1) a week or so ago in my front yard. What’s the connection with SF/F? Hey, you can just imagine it’s a giant bird sitting on a flying saucer of some sort. The caption should give you a starting point.

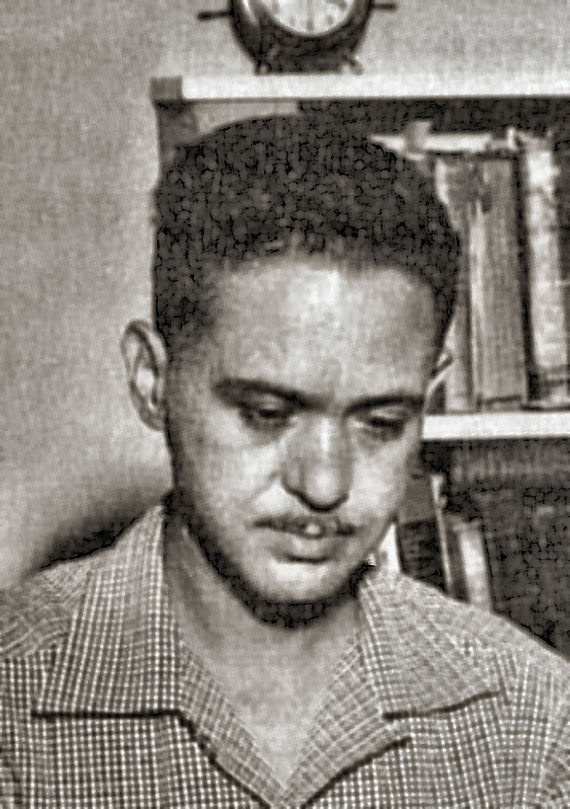

If you read my review of Wildside Press’s Cyril Kornbluth book, and if you’re on Facebook, you might have noticed that someone (it might have been John W. Campbell award-winning genre writer Amy Thomson) asked when I was going to do one for Henry Kuttner. Well, ask no more, ’cos here’s Henry!

Henry Kuttner (Figure 2) was born the same year as my parents, 1915, and died when I was only 11 years old—sadly, he was only 45 when he died. You’d think I wouldn’t even know who he was, but some of his work was so popular that it kept on being reprinted up until somewhat recently. The most recent reprint of a Kuttner collection was, I believe, Robots Have No Tails, from Planet Stories in 2014, of a 1952 collection of his “Gallagher” stories. (More on that later.) As far as I know, there are few extant print books of Kuttner’s work (more on that, too, later). Although their website is hard to navigate, I believe there are at least two Kuttner collections in the Megapack series.

Kuttner wasn’t part of the New York literary circle called “The Futurians”; rather, he started his literary career in Los Angeles, working for his uncle’s literary agency (Wikipedia). You can click on the Wikipedia link at left for more information about him; I’d just like to hit a few highlights of his genre career. His genre career? Yes, he wrote novels that were not genre novels, and probably lots of non-genre short stories too. But he was a prolific genre author, both alone and in collaboration with his wife, C. L. Moore under the pseudonym Lewis Padgett. He had lots of pseudonyms, but Padgett and Lawrence O’Donnell were two favourites (and for fans of Robert A. Heinlein and Spider Robinson, he also—according to ISFDB—used Woodrow Wilson Smith on at least one occasion).

Filmgoers might recognize his name from two filmic versions of his work: the short story “Mimsy were the Borogoves” was filmed under the title The Last Mimzy; it had a fair amount of correspondence with the actual story, but no more than is usual for film adaptations of good stuff. (Snark, snark.) The same holds true for The Twonky, a b/w movie adaptation of the short of the same name, starring Hans Conreid. While the movie had its moments, it was nowhere near as funny/scary as the short story that spawned it.

Although he wrote serious SF and “Cthulhu Mythos” fiction (he and his wife were members of a group that corresponded with H.P. Lovecraft), he is perhaps best remembered for his humourous genre short fiction. And that’s why I, in particular, always remembered him and looked for his stories. He wrote a number of series, but three in particular are wonderful and still work today, more than half a century after they were written: the “Gallagher” and “Hogben” stories, both humourous series; and the “Baldy” stories, which were not humourous, but serious examinations of what might possibly happen if radiation caused mutations in the human genome that were passed on, specifically, baldness and telepathy.

When the “Baldy” stories were written, in the late 1940s (about the time I was born) to the mid-1950s, there was a lot of concern that radiation—not only from a possible nuclear war, but also from laboratory experiments and atomic testing and so on—could produce viable mutations that might reflect unfavourably on non-mutants; novels and stories of the period are full of mutation stories. (One of the best was Judith Merril’s “That Only a Mother”; I believe the mutation in that one was caused by atomic bomb testing.) Then in the ‘50s, it became common to have mutated animals and plants in movies, wreaking havoc on the human race. But mutated humans came first. They appeared at various times and in various publications under the Padgett name and/or Kuttner’s own name.

It’s been a while since I’ve read the Baldy stories; according to ISFDB, there are only six of them, which I’ll list in the year in which they appeared; many of these stories are available from various people as ebooks. There were: “The Piper’s Son” (1945); “Three Blind Mice” (1945); “The Lion and the Unicorn” (1945); “Beggars in Velvet” (1945); and, finally, “Mutant” (1953) and “Humpty Dumpty” (1953). (Amusingly, the Russian versions credit Генри Каттнер, which transliterates to “Genry Kattner.” Hey, I found it funny.) I’m unaware of a single collection available right now with all the Baldy stories, however.

There is, however (Figure 4), a “Best of” collection available in ebook, though it appears the print versions are either out of print or way overpriced (or both). I believe the Best of Henry Kuttner contains seventeen stories, including several of the Gallagher stories, as well as “The Twonky,” “Mimsy Were the Borogoves,” and one of my personal faves, “Housing Problem.” The link will take you there, by the way. Just so you know, Gallagher was a “mad” inventor, a man who could invent anything to solve any problem except his own. His problem was that he couldn’t invent anything sober; and when sober, he couldn’t remembe how, why, or what he had invented, such as the vain robot that spends all its time admiring itself in the mirror. “You can’t appreciate me,” the robot tells Gallagher, “You don’t have enough senses.” (The cover of a book of Gallagher stories is shown in Fig. 3.) The Best of Henry Kuttner also contains two Hogben stories: “Cold War,” and “Exit the Professor.”

And now we come to a book that is not only available both in ebook and in print format, but also contains a whole series of stories by Kuttner that embody some of the best of his offbeat sense of humour. Check out Figure 5; I’m referring here to the Borderlands Press book The Hogben Chronicles, edited by Pierce Watters and F. Paul Wilson. (Check out the link for ordering information.) What’s a Hogben? I hear you ask.

A Hogben is someone you will only meet once in a lifetime for the first time; I don’t recollect exactly which one I read first, but I was hooked, same as when, in those long-ago days, I read my first Feghoot in F&SF. (I’ll explain Feghoots some other time.) The Hogbens are a mythical Kentucky family from back in the piney woods somewheres, who inhabit a very short series of tall tales by the aforementioned Kuttner writing with his wife under the Padgett name. (I understand that, similar to the way Leo and Diane Dillon used to work their award-winning art, Kuttner and Moore worked so seamlessly together that they couldn’t tell who had written what.).

There are only, sadly, six Hogben stories, ranging from the first 1941 tale, “The Old Army Game,” in which we’re introduced to this weird family. At that time, Kuttner hadn’t completely developed this family; he was later to add a few family members and develop their odd attributes. The last one, “Cold War,” was written in 1949—and may actually be the one I first encountered. Sadly, Kuttner died prematurely of a heart attack and never continued the series.

I don’t want to get into too much detail about the Hogbens themselves; I will briefly mention Saunk, who thinks of himself as the runt of the family at something over six feet tall; the baby, who with his tank, weighs about 300 lbs.; Grandpa, who lives in the attic and usually speaks in Elizabethan English; and Paw, who sometimes forgets to go invisible when he flies around. Saunk himself can barely remember London in the time of Samuel Pepys. That should give you enough of a handle to know what kind of humourous story can be made of such protagonists.

Suffice it to say that without remembering it, my own fiction has, from time to time, been influenced by the Hogbens, and these stories have also influenced such people as Neil Gaiman (who wrote the foreword to this volume); Alan “Watchmen” Moore; and F. Paul Wilson, author of “The LaNague Federation” and “Repairman Jack” series, who co-edited this volume; Joe R. Lansdale appears to be one; and also Thomas F. Monteleone, award-winning author—whose own first story appeared in Amazing Stories in 1972!

And, I’m sure, there are many, many more. I hope you check out Henry Kuttner if you don’t already know him; I guarantee you’ll enjoy yourself.

Comments on my column are always welcome. You can here, or on Facebook (in the several Facebook groups I post in). All your comments, good or bad, positive or negative, are welcome! (Just keep it polite, okay?) My opinion is, as always, my own, and doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of Amazing Stories or its owner, editor, publisher or other columnists. See you next time!

Editor’s notes: The Twonky is viewable on Youtube –

and Haffner Press has published a few previously unpublished stories by Kuttner

(Your editor is a Kuttner fan too)

I think the Baldy stories were collected as “Mutant,” which you can find if you look.

Jeff, you’re right–and I had forgotten that. Thanks for reminding me!

Thanks for the additions, Steve. I did know about the YouTube version of The Twonky; I’ve seen a much cleaner version than that, if I remember correctly. But I had forgotten that it was written by Arch Oboler (“Lights Out”)! And I’ll have to check the Haffner Press site. I guess there are more Kuttner fans out there than I thought!