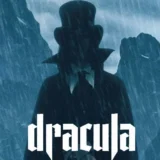

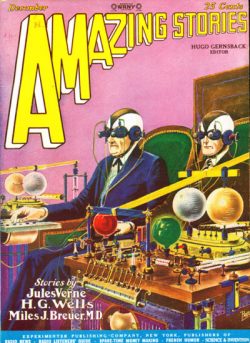

Two men, wearing ordinary-looking suits and seated in ordinary-looking chairs, are surrounded by extraordinary machinery. Each man has an elaborate apparatus standing next to his chair; it is impossible to tell form the image exactly what either device is intended to achieve, but it is somehow associated with vision. Each man wears a headset, connected to his respective apparatus by wires, with a pair of binocular-like extensions over his eyes.

Two men, wearing ordinary-looking suits and seated in ordinary-looking chairs, are surrounded by extraordinary machinery. Each man has an elaborate apparatus standing next to his chair; it is impossible to tell form the image exactly what either device is intended to achieve, but it is somehow associated with vision. Each man wears a headset, connected to his respective apparatus by wires, with a pair of binocular-like extensions over his eyes.

The men appear tense, as though preparing for visions the likes of which they have never seen. It was December 1927, and Amazing Stories was taking its readers to another set of new worlds.

Hugo Gernsback’s chosen topic for this month’s editorial is psychology – specifically, the workings of human curiosity:

It is a part and parcel of the makeup of the average human to be most irritated by something that is unknown to him. If we traced this feeling to its lair, we would perhaps have need of a psychologist for the ultimate explanation. […] Often, also, the more highly learned a person is, the greater the irritation. Thus, when a scientist comes along with something totally unorthodox—some new fact which may not be discernible as fact immediately—his fellow scientists are usually the ones who become most irritated and loud in their denunciations. Thus it was with Galileo, when* he attempted to prove that the earth did not stand still, but spun around on its axis—a monstrous piece of “nonsense” in those days. It not only went against the grain and all inborn instinct, but against the Church as well.

It was, and still is true in the case of Einstein and his Theory of Relativity. Most of these theories have been proven after many years of wrangling among scientists and mathematicians, yet even today most of them are confirmed doubters.

This brings Gernsback to that oldest of Amazing Stories chestnuts – scientific plausibility in fiction. His tone here is rather angrier than usual, indicating that some of the magazine’s letter-writers had got themselves under his skin:

This is true, also, of a certain class of Amazing Stories scientifiction readers, a class, by the way, which we are happy to state, seems to be in the minority. This class is always ready, to tear and claw at any author who comes along with a new idea which, “for the time being, may be contrary to fact, although it may still lie within the realm of science. Usually when such a scientifiction story is published, the howl raised by this class of readers is long and lusty, and most vitriolic. They give no quarter, and are loud in their denunciations, and go to great lengths in venting their opinions as to why such and such statement could never come true. Yet, before the ink is dry, it has happened that a scientifiction prediction has become a fact. Undaunted, however, the Doubting Thomases are inclined to close their eyes and minds against every fact and glibly say, “We don’t believe it anyhow.” The old story of “There ain’t no such animal.”

As a rejoinder to such thinking, Gernsback discusses two recent developments that might, in the recent past, have been dismissed as unscientific nonsense. One is the electronic music of Léon Theremin; Gernsback describes how he had himself devised a similar instrument to Theremin’s invnetion, called the Pianorad, although his was more rudimentary as it required a keyboard to use. The other development cited by Gernsback is Robert W. Wood’s experiments in using high-powered ultrasound to crack ice, kill fish and crumble a candle suspended in water.

Despite Gernsback’s clear interest in sonic technology, this topic does not come up in December 1927’s batch of stories. Instead, if there is a dominant theme this month, it is travel to new territories — be they on land, in the sky, under the sea, or even beyond the visible spectrum…

Robur the Conqueror, or The Clipper of the Air (part 1 of 2) by Jules Verne

Amazing Stories dusts off another Jules Verne novel for republication, this time an 1886 story originally known as Robur-le-Conquérant. The story opens with an unidentified flying object seen over many countries, plays music; meanwhile, the Weldon Institute – run by a wealthy American known as Uncle Prudent – has developed a vast balloon called the Go-Ahead. But the project is opposed by Robur, a larger-than-life figure who claims who claims to possess “a constitution of iron, a healthy vigor that nothing can shake, a muscular strength that few can equal, and a digestion that would be thought first class even in an ostrich”.

Amazing Stories dusts off another Jules Verne novel for republication, this time an 1886 story originally known as Robur-le-Conquérant. The story opens with an unidentified flying object seen over many countries, plays music; meanwhile, the Weldon Institute – run by a wealthy American known as Uncle Prudent – has developed a vast balloon called the Go-Ahead. But the project is opposed by Robur, a larger-than-life figure who claims who claims to possess “a constitution of iron, a healthy vigor that nothing can shake, a muscular strength that few can equal, and a digestion that would be thought first class even in an ostrich”.

To Robur, guided balloons such as the Go-Ahead are doomed to fail, and that the true future of manned flight lies in mechanised vehicles. The ballooning enthusiasts, unimpressed, give the speaker the ironic nickname of Robur the Conqueror. The crowd quickly becomes violent, but Robur escapes their wrath – by taking to the air. Uncle Prudent is subsequently abducted, along with the institute secretary Phil Evans and Prudent’s racially-stereotyped black valet Frycollin. They find themselves prisoners on board the Albatross, Robur’s vast flying machine.

As is typical for his work, Verne uses his high-flying story to show his readers the wonders of technology and of far-flung locations. He includes lengthy digressions on the history and theory of manned flight, introducing three main varieties of guided flying machine – the aeroplane, the helicopter and the ornithopter, or mechanical bird – and detailing Robur’s exact reasons for his choices in designing his Albatross, the mechanics of which are likewise described at length. Where the inhabitants of Nemo’s Nautilus saw all manner of undersea sights, Robur’s captives are treated to aerial vistas; this first part of the story ends with treacherous voyage through the Himalayas to India.

“The Country of the Blind” by H. G. Wells

This 1904 story tells of a remote valley in Ecuador, the inhabitants of which enjoyed a lush, bountiful environment, but over time became stricken with hereditary blindness. Due to their simple way of life, the people of the valley were able to survive from generation to generation despite having lost their sense of sight.

This 1904 story tells of a remote valley in Ecuador, the inhabitants of which enjoyed a lush, bountiful environment, but over time became stricken with hereditary blindness. Due to their simple way of life, the people of the valley were able to survive from generation to generation despite having lost their sense of sight.

Nunez, a mountaineer, finds himself in the valley and comes to realise that the population – who initially fail to notice his presence – are blind. The locals are intrigued by their visitor, running their hands over him and listening to him speak; they conclude that his senses and mind are underdeveloped, as he stumbles over objects and uses such meaningless words as “sight”. Nunez finds that the people of the valley have only dim memories of ever having sight; memories that now exist only in legends, which are questioned by the wiser people of the culture.

The locals have developed an entire mythology derived from their sightless interpretation of their surroundings – for example, they believe the sound of birds to be the singing and wing-beats of angels. They divide the time into warm and cold, rather than day and night; the warm period is when they sleep, much to the annoyance of Nunez, who must fumble around in the cold night while he lives amongst them.

Nunez scoffs at their way of life, and regards himself as their “heavensent king and master”, But his attempts to subjugate them fail, partly because of his natural aversion towards harming blind people, and partly because they turn out to be more capable of self-defence than he had expected. He decides to join their society, and even finds love with one of the valley’s maidens; only when he faces the prospect of being blinded so that he is deemed worthy to marry her does he decide to flee.

Lost civilisation stories frequently dehumanise the inhabitants of their imaginary lands, but in “The Country of the Blind” Wells employs a touch of Swiftian satire: is Nunez really less blind than the people of the valley, or does he merely have a different part of the elephant?

“The Undersea Express” by J. Roaman

“For years I had planned a voyage to London in one of the big I. E. C. submersibles,” declares the narrator of this tale, “yet never until this day had I been able to adjust my business and other affairs so as to arrange the trip.” The protagonist, a denizen of the year 2500, is finally granted a trip in one of the International Express Company’s freight submarines. The skipper, Captain Judson, quells the protagonist’s doubts about the safety of this transport method, and during the journey points out the various underwater harbour lights used to guide the submarine.

“For years I had planned a voyage to London in one of the big I. E. C. submersibles,” declares the narrator of this tale, “yet never until this day had I been able to adjust my business and other affairs so as to arrange the trip.” The protagonist, a denizen of the year 2500, is finally granted a trip in one of the International Express Company’s freight submarines. The skipper, Captain Judson, quells the protagonist’s doubts about the safety of this transport method, and during the journey points out the various underwater harbour lights used to guide the submarine.

Trouble strikes when another submarine, the Bristol, scrapes an iceberg; Judson’s vessel has to provide aid, even if this means delaying its tightly-scheduled delivery. The narrator looks on as two crew members depart the submarine in copper diving suits to rescue the crew of the ruined Bristol. Despite some tense moments, Judson succeeds in rescuing the crew members – and delivering the shipment on time, as well.

“In these days of trans-Atlantic flights, one would think that the idea of an undersea express would be rather far-fetched”, runs the editorial introduction to this slight tale. “Nut this need not necessarily be so, for the simple reason that when trans-Atlantic flying becomes commonplace, as it will during the next few years, such traffic, due to the high cost, will most likely be for passengers. The heavy freight will continue to travel by ocean liners, or perhaps by the undersea express, for better speed as no storms will impede the progress of a subsea vessel.”

“Hicks’ Inventions With a Kick: The Electro-Hydraulic Bank Protector” by Clement Fezandié

Long-suffering O’Keefe gets another unwanted visit from Hicks, whose inventions always end in disaster (see also his Automatic Self Serving Dining Table and Automatic Apartment). But this time O’Keefe finds himself intrigued: Hicks’ latest client is a notoriously tight-fisted banker named E. E. Croffitt. And so, he turns up at the unveiling (on Friday the 13th, no less) of Hicks’ Electro-Hydraulic Bank Protector, an event attended by some notables of the banking world.

Long-suffering O’Keefe gets another unwanted visit from Hicks, whose inventions always end in disaster (see also his Automatic Self Serving Dining Table and Automatic Apartment). But this time O’Keefe finds himself intrigued: Hicks’ latest client is a notoriously tight-fisted banker named E. E. Croffitt. And so, he turns up at the unveiling (on Friday the 13th, no less) of Hicks’ Electro-Hydraulic Bank Protector, an event attended by some notables of the banking world.

The aim of his invention, Hicks explains, is not only to halt bank-robbers but to scare them away from ever robbing a bank again:

If the police are unable to catch the criminals, and the courts are unable to mere out proper punishment to instil sufficient respect in the minds of those who intend to do evil, then it is up to the citizens to catch the criminal, so utterly and unfailingly defeat him, that even after he has served his term, he will remember the experience with feelings of unalloyed and unforgettable terror.

Inspired by the efficiency of firefighters when it comes to dispersing riots, Hicks has his machine shoot streams of pressurised water at would-be robbers. One of the men attending the demonstration agrees to serve as a target, but disaster strikes when the fellow is thrown back so far by the water that he hits a switchboard.

The assembled observers find themselves pummelled by geysers shooting out of the security arrangement. As they try to regain their composure, they are then bombarded with great globs of glue intended to stop robbers in their tracks. More water follows, this time boiling hot. While the drama unfolds, O’Keefe muses to himself that, if nothing else, the system has demonstrated its effectiveness at halting crooks. But then a group of robbers turn up, and take advantage of the chaos to fleece the joint.

“Below the Infra Red” by George Paul Bauer

Protagonist Barton meets with one Professor Carl Winter, who introduces him to the theory that creatures exist outside of the visible spectrum: “there may be beings who live in different planes from ourselves, and who are endowed with sense-organs like our own, only they are tuned to hear and see in a different sphere of motion.” The professor later invites Barton to try out his new invention – an elaborate viewing device that allows users to see below the infra-red.

Protagonist Barton meets with one Professor Carl Winter, who introduces him to the theory that creatures exist outside of the visible spectrum: “there may be beings who live in different planes from ourselves, and who are endowed with sense-organs like our own, only they are tuned to hear and see in a different sphere of motion.” The professor later invites Barton to try out his new invention – an elaborate viewing device that allows users to see below the infra-red.

Donning the goggles of the apparatus, Barton is confronted by a vast cathedral populated by men and women “of such physical perfection as to remind me of the fabled gods and goddesses of ancient Greece.” The professor is invisible to him, as is his own body, but Barton is nonetheless able to touch his companion.

These people speak a language unknown to Barton, but thanks to “some marvellous process of the mind” he is able to pick up translations telepathically. After this comes another strange occurrence: “I felt that I was gradually rising out of my physical body. It was an indescribable sensation. It seemed that I, the soul, was slipping out of my invisible physical shell, like a snake slipping out of its last year’s hide.” Barton finds that he is now visible; the professor undergoes a similar process, becoming not only visible but visibly younger.

“[T]he vibrations of our physical bodies were raised to such a degree that our spiritual bodies have temporarily become liberated and separated from our physical shells”, explains the professor. However, he notes that they are not seeing their spiritual bodies, but rather a “vito-chemical substance” that covers these bodies.

The people in the cathedral – the Alanians – notice the visitors, who are warmly greeted by the sibling rulers Eloli and Ealara. Barton and Winter see the exquisite art of this new land and sample a delicious beverage, but the idyll is shattered when one of the locals announces the coming of the Pluonians. “The Pluonians are a terrible enemy, a lower race than ours, who hate us because of our progress and our harmony among ourselves”, Eloli tells the visitors. “Occasionally they enter into ruthless warfare against us; often they come in the night and carry off our women and children.”

In contrast to the white and blonde Alanians, the Pluonians are black-skinned, hairy and ape-like. Instead of using weapons the combatants on both sides merely stare into each other eyes, the fighter with the strongest will-power triumphing through a form of hypnosis. Eloli kills the Pluonian king, and the Alanians return in victory.

Disaster strikes when Barton falls under the mind-control of Pluonian prisoners and frees them, allowing them to kidnap Ealara. Barton successfully rescues her from the hellish land of the Pluonians, and realises that she is his soul-mate – but is then abruptly brought back to the mundane world as a result of a storm interfering with the equipment. The professor subsequently passes away from heart failure, and Barton decides to return to the Ealara’s world alone.

“Below the Infra Red” is an uneven tale. At the start, when the characters discuss beings that exist beyond the visible spectrum, the reader might be expecting something along the lines of H. G. Wells’ weird “The Plattner Story”. Once Barton and Winter see the Alanians, it looks as though the story belong to a contemporary subgenre in which characters invent an incredible new viewing device, only to become passive observers of a heavily anthropomorphised alien milieu (see also Charles C. Winn’s “The Infinite Vision” and Garret Smith’s Treasures of Tantalus). By its end, it has become a heavily condensed reworking of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ A Princess of Mars.

The conflict between the people of Eloli and a race of ape-men carries an obvious suggestion of the Eloi and Morlocks in Wells’ The Time Machine; but Wells’ class-based satire is absent, replaced with racist overtones (“There were many nations on the sub-infra plane, most of them white and advanced peoples. The rest, to which the Pluonians belonged, were primitive and dark-skinned”; “We turned our attention again to the scene of conflict, and noted to our joy that the whites were unmistakably gaining. A great many more black warriors than white were lying on the ground”).

“Crystals of Growth” by Charles H. Rector

Professor Brontley invites his friend Jameson to see the results of his latest experiment: a food with such a high concentration of nutrients that it is able to visibly alter a person’s size almost instantly. The professor swallows two pieces of the crystalline food substance, and Jameson watches in awe:

Professor Brontley invites his friend Jameson to see the results of his latest experiment: a food with such a high concentration of nutrients that it is able to visibly alter a person’s size almost instantly. The professor swallows two pieces of the crystalline food substance, and Jameson watches in awe:

For perhaps five or six seconds no change was apparent; then a shudder passed over his frame and before my very eyes he commenced to increase in size. You have probably been away from home for some time and upon your return noticed the increased stature of some young friends. You remarked how much they had grown while you were away. But here before my naked eyes, growth was taking place immediately. It was almost unbelievable.

The professor reaches twelve feet in all, and speaks of the benefits his crystals will have on mankind (“No more under-developed children! no more short men and short women”). Jameson realises that the professor’s mind has been altered as well as his body, turning him into a fanatic; when Jameson turns down the opportunity to swallow a crystal himself, the professor loses his temper and physically attacks him.

Jameson passes out. He is awoken by a friend, who dismisses his story as a bad dream – but the professor has vanished, indicating that the ordeal may actually have taken place.

“Crystals of Growth” is a brief story that hits on a premise but comes up with absolutely nothing to do with it, and so settles for having its giant man simply vanish without explanation. The author never returned to science fiction, vanishing just as completely as Professor Brontley.

“The Riot at Sanderac” by Miles J. Breuer, M.D.

This story takes place in Sanderac, a fictional American mining town. Half of its population consists of foreign labour, including Russian communists, but despite their differences the people exist in peace.

This story takes place in Sanderac, a fictional American mining town. Half of its population consists of foreign labour, including Russian communists, but despite their differences the people exist in peace.

An engineer named Grant builds an elaborate machine that combines an organ-like keyboard with what resembles a giant radio transmitter. As Grant works this device, his friend – who narrates the story – finds his emotions being affected, as he first becomes depressed before collapsing into laughter and finally being consumed with anger. Grant explains that the machine has been altering his emotional state by bombarding him with electrons.

Grant arranges a public demonstration of his machine, with his Russian assistant Sergei operating it. But the demonstration ends in disaster: Sergei, a skilled musician whose wife and daughters were killed by Bolsheviks, turns the audience into an irate mob; at Sergei’s behest, the mob launches an arson campaign against the communist population of Sanderac.

Another three-page story, but a considerably stronger one than “Crystals of Growth”. With “The Riot at Sanderac”, Miles J. Breuer delivers a brief but solid treatment of the mind-control theme.

Discussions

As usual, the magazine’s letters section is filled with spirited discussion amongst readers. Some are amazed, others not so amazed…

“When I first picked up your magazine and glanced at the cover”, writes Marguerite Keeley, “I said ‘Amazing Stories!’ Why not ‘Fairy Stories?’ –and my brother and I laughed together. But although I’m Irish, I’ll admit defeat and after I’d read your selection of incredible facts and read a few stories I became intensely interested and now I am a devoted reader.” She goes on to complain about over-critical letters, requests more stories about chemistry, asks if Amazing Stories has its own radio station (in a manner of speaking, it did – WRNY being owned by the magazine’s publishing company) and asks if A. Hyatt Verrill’s “The Man That Could Vanish” was a true story. “We have not been favoured by many letters from readers of the fair sex”, notes the editor in response. “We would like to hear from more of them.”

“Wild West stories and the old threadbare love plots long ago ceased to thrill me”, writes Sterling Bunch. “I began searching for ‘out of the ordinary’ stories in libraries and in the current magazines. I soon read all of Wells, Verne, Defoe, Poe and the few other older classic writers of this type of story and of story and I began wishing that some enterprising editor would publish a magazine featuring this kind of story. Amazing Stories is a very satisfactory materialization of this wish.” Bunch’s praise is tempered with a complaint that some of the stories are too negative in outlook: “Don’t we see enough of the morbid in real life without bringing it too forcibly into fiction? After all, isn’t it just as probable that an invading race from Mars or Venus would bring good to the world as bad?” The letter concludes by asking for more stories set in the fourth dimension (“Relativity and the Fourth Dimension have already radically changed our scientific thought”)

Frank Carpenter, Jr. expresses disdain for magazine fiction in general (“I much prefer spending my time reading Romain Rolland and Fyodor Dostoevsky”) but shows appreciation for Amazing, particularly T. S. Stribling’s “The Green Splotches”. He suggests that “a plainer or at least a more simple cover would be more appropriate as it would set Amazing Stories above the plane of terrible magazines that line the newsstands with their ‘hair-raising’ pictures.” Harry Hess disagrees with this latter complaint: “Each month the cover of Amazing Stories is very attractive. I am sure if the magazine dealers would place a copy of the magazine in a display window where the public could see it, more would be sold…. In most magazine stores it is partly concealed by other magazines.”

W. P. Donnelson objects to Ray Cummings’ “Around the Universe” (“at the rate of 740,000,000 miles per second… the Creator alone knows what the increased vibrations would do to the electrons and protons that are supposed to constitute the atoms of a Flyer or any people therein”). In contrast, Bob Emmett is amused by Cummings’ story (“We might be floating around with our little world in the space between the air molecules of the other world’s atmosphere”) and expresses hope that the magazine will increase its publication rate. Another letter-writer, Joseph C. Collins, ventures that once a month is sufficient – at least until the magazine has had more time to establish itself.

T. I. Saarels attacks the “disgraceful” quality of the binding and the “abominable” illustrations (“I am in favor of plenty of pictures, but not such lifeless and inanimate imitation cartoons”) before going on to attack a number of the magazine’s authors.

A discussion point in previous issues had been a proposed science club for young men; this topic comes up once more in the present issue. Haiger E. Lindgren announces that he has been trying to build interest amongst his friends for such a club; Edgar Orr also approves of the idea, while admitting that he is above the proposed age limit.

Glenn D. Rabuck attacks some of the magazine’s critics, comparing those who find flaws in the stories to “those who ‘view with alarm’ the Atlantic and Pacific flights, calling them the exploits of ‘fools’… It makes me think of some other fools like the Wright brothers and so on”. Unlike some of these critics, Rabuck also defends the magazine’s comedic stories.

According to the letter, H. G. Wells is “overexploit[ed]” in Amazing, A. Merritt is “good but too imaginative” and unscientific; Jules Verne’s stories are “all right” but have “too much of a dry journalistic flavor”; Burroughs is unworthy of even being printed in the magazine (“I have read wholly or partly every story that Burroughs has written before I knew better, and find him to be the most magnificent liar I have seen in print”); Ray Cummings “has an abominable habit of going into out of the way places for his heroines” (“for the love of Pete, make it the rule to keep ’em on the earth”); and the comedic invention tales are “nothing more than rank imitations of Edgar Franklin’s old ‘Hawkins’ stories of 24 years ago”. On a less critical note, the letter requests a number of old stories to be reprinted, including a number from All Story. Edgar Orr likewise argues that Burroughs’ fiction “hardly belongs in your magazine” due to its fanciful nature, although he offers a more favourable opinion on the stories themselves.

Edgar Rice Burroughs, as it happens, is a recurring topic in this month’s letters column. Frank John M. Sturn becomes the latest reader to send in a newspaper clipping – this time an article from the Memphis Commercial Appeal about a South African boy being reared by baboons, recalling Tarzan. Earlier letter-writers had objected to anti-German bias in Burroughs’ stories; John W Bell went to the trouble of writing to Burroughs on this topic, and received the following reply:

I am very sorry that a couple of my stories have given the impression that I do not like Germans. These stories were written when the feeling against the Germans was very high in this country and to the tremendous amount of anti-German propaganda during the war. I realise now that much of this was exaggerated and I know that it does not do any of us any good to foster enmity and hatred.

Burroughs also comes up in a letter from I. M. Lichtigman:

Of course the stories of Edgar Rice Burroughs are full of incident, but the incidents portrayed are mostly of the blood and thunder sort. Some minds my prefer stories in which the hero kills Brontosauri with his naked hands, in which gorillas are hatched out of eggs and gradually turn into human beings of a high order ,in which on every page the hero saves the heroine, and slays a score of animals or men. But what scientifiction is there in a plenitude of gory incidents? If stories like those are real, then so are “Perils of Pauline,” and “Nick Carter.” It is just in the atmosphere created by such masters as Wells, Verne and Conan Doyle that their greatness lies. They can make a highly imaginative story such as an attack by Martians read like the story of an eye witness to the actual occurrence.

Responding to a letter in the October issue asking why The War of the Worlds failed to portray aeroplanes sent out against the Martians, Lichtigman makes the salient point that aeroplanes did not exist in 1898. Finally, the letter provides some thoughts on time travel, including a lengthy take-down of A. Hyatt Verrill’s “The Astounding Discoveries of Doctor Mentiroso”.

Speaking of which, this issue of Amazing runs the solution to the puzzle of Verrill’s story:

Read My Profile