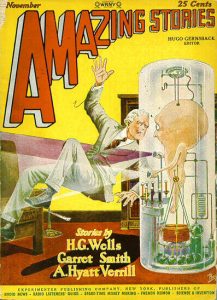

A man looks over his shoulder only to come face to face with a weird being. This creature resembles a large, oddly-shaped foetus, and inhabits a transparent cylinder; inside are various pieces of technology, some of which are attached to the creature’s body. Unsurprisingly, the man is recoiling in fright. It was November 1927, and Amazing Stories was back once again.

A man looks over his shoulder only to come face to face with a weird being. This creature resembles a large, oddly-shaped foetus, and inhabits a transparent cylinder; inside are various pieces of technology, some of which are attached to the creature’s body. Unsurprisingly, the man is recoiling in fright. It was November 1927, and Amazing Stories was back once again.

In this month’s editorial, Hugo Gernsback ponders how the advance of scientific understanding will render certain science fiction concepts obsolete. In particular, he writes about how space exploration would damage the notion of intelligent life on other planets in the solar system:

If it becomes possible to navigate a space flyer outside of the terrestrial atmosphere, even if only to such a comparatively near body as the moon, then immediately an important popular conception becomes a certain impossibility. I refer to the present inhabitation of reasoning beings on other planets, at least of our own universe.

The reason is simple. If we can navigate a space-flyer, let us say, to Mars or Venus, then it may be assumed that none of the planets is now peopled by reasoning, intelligent beings.

However, Gernsback includes a few caveats in his argument. He acknowledges that now-extinct races from Mars or the Moon may have landed on Earth in the distant past but “had to turn back, because the shores of the earth several million years ago were probably unfit to set foot upon.” He also speculates that races on other planets may have developed space transport, but avoid using it due to potential hazards such as meteors or the cosmic rays recently identified by Robert Andrews Millikan. AS it happened, greater understanding of the solar system did indeed rob humanity of its hypothetical neighbours – not that this prevented writers from imagining a universe swarming with alien life.

However, extraterrestrial life is not a particularly significant theme in this month’s issue of Amazing Stories: with one exception, its tales take inspiration not from alien worlds, but from Earth – past and future.

“The Machine Man of Ardathia” by Francis Flagg

A writer named Matthews dozes off while working on his book (“a critical analysis of the fallacies inherent in the Marxian theory of economics embracing at the same time a thorough refutation of Lewis Morgan’s ‘Ancient Society’”) and is awoken by a sudden flash of light. He sees that the area in the room once occupied by a rocking chair is now occupied by a transparent tube holding a squat, bulbous-headed humanoid. This lifeform introduces itself as a Machine Man of Ardathia, originating 30,000 years in the future before travelling back through the fourth dimension. The visitor is unable to explain the exact process to the narrator – after all, the latter is merely a primitive man from a prehistoric age.

A writer named Matthews dozes off while working on his book (“a critical analysis of the fallacies inherent in the Marxian theory of economics embracing at the same time a thorough refutation of Lewis Morgan’s ‘Ancient Society’”) and is awoken by a sudden flash of light. He sees that the area in the room once occupied by a rocking chair is now occupied by a transparent tube holding a squat, bulbous-headed humanoid. This lifeform introduces itself as a Machine Man of Ardathia, originating 30,000 years in the future before travelling back through the fourth dimension. The visitor is unable to explain the exact process to the narrator – after all, the latter is merely a primitive man from a prehistoric age.

The Ardathian goes on to outline the changes undertaken by humanity across the story’s future-history. Over time, humans began to make ever-growing use of technology, to the extent that its evolution developed in relation to various mechanisms. With the development of artificial reproduction, the race lost biological sex; with sophisticated tools at its disposal, its limbs withered into tentacle-like vestiges. The resultant post-humans have seen three distinct phases: first came the Bi-Chanics, then the Tri-Namics, and now the Machine Men, who exist as small biological nuclei surrounded by elaborate apparatuses.

Matthews is disturbed by this prospect. He contemplates whether or not the Ardathians have souls, and asks the visitor about the loveless, joyless life it must surely lead. The Ardathian responds that outgrowing emotion is a beneficial process, and that it is Matthews who truly remains entrapped. Matthews neighbour knocks on the door, interrupting the conversation; when he enters, the Ardathian has vanished. A postscript reveals that Matthews ended up in an asylum.

H. G. Wells is namechecked near the start of “The Machine Man of Ardathia”, and his influence on this story is hard to miss. For one thing, Wells had already touched upon the subject of an intelligent species evolving around its mechanical tools in The War of the Worlds; the idea would later inspire Doctor Who’s Daleks. But it is also hard to miss that, had Wells written “The Machine Man of Ardathia”, it would have had a stronger narrative, rather than serving mainly as a lecture on a hypothetical future.

“A Story of the Stone Age” by H. G. Wells

Moving from humanity’s distant future to its primitive past, here we have an 1897 story by H. G. Wells. A young woman, Eudena, runs into fellow tribesperson Ugh-lomi and learns that the that he is being pursued by the rest of the tribe, commanded by Uya the Cunning Man – for this was a time when humanity hunted its own kind for sport:

Moving from humanity’s distant future to its primitive past, here we have an 1897 story by H. G. Wells. A young woman, Eudena, runs into fellow tribesperson Ugh-lomi and learns that the that he is being pursued by the rest of the tribe, commanded by Uya the Cunning Man – for this was a time when humanity hunted its own kind for sport:

They knew there was no mercy for them. There was no hunting so sweet to these ancient men as the hunting of men. Once the fierce passion of the chase was lit, the feeble beginnings of humanity in them were thrown to the winds. And Uya in the night hard marked Ugh-lomi with the death word. Ugh-lomi was the day’s quarry.

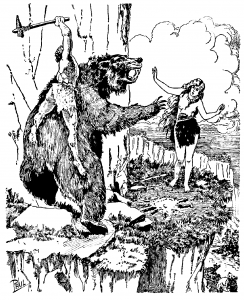

The two escape and relocate to a new area of land; Uya follows, only to be slain by Ugh-lomi – who has recently invented the axe. The story follows Ugh-lomi’s subsequent exploits including his attempts to ride a horse, his invention of a spiked club, his return to the tribe and his eventual death.

The story attempts to place its reader into the mindset of primitive humans, complete with supernatural beliefs: Ugh-lomi’s dreams of fighting with Uya are portrayed as battles between the two men’s spirits, while Ugh-lomi believes that, by eating animals reincarnate from men, he will inherit attributes of those men. But at the same time, Wells shows no qualm about abruptly returning to a modern perspective, as when his narrative voice compares the noises of the hyenas to “a party of Cockney bean-feasters”

Alongside the viewpoints of both prehistoric and modern people are the viewpoints of animals. The story takes on a somewhat whimsical flavour during these passages, as when we see humanity from the perspective of a cave bear:

This invasion perplexed him. He noticed these new beasts were shaped like monkeys, and sparsely hairy like young pigs. “Monkey and young pig,” said the cave bear. “It might not be so bad. But that red thing that jumps, and the black thing jumping with it yonder! Never in my life have I seen such things before.”

Treasures of Tantalus by Garrett Smith (part 2 of 2)

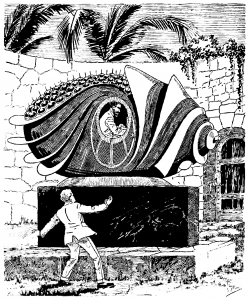

Garrett Smith’s novel of Professor Fleckner and his all-seeing telephonoscope takes some curious paths in its latter half. Protagonist Blair, aided by his friend Priestley, continue to use Fleckner’s telephonoscope in their attempt to locate the hidden treasure of the criminal syndicate that threatens to take over the world. Making use of his invention’s ability to project images as well as transmit them, Fleckner infiltrates the syndicate and masquerades as its leader so as to learn its secrets. The professor’s motives are less than altruistic, however: the more time he spends as a spy amongst the criminals, the harder he becomes to distinguish from the crooks themselves.

Garrett Smith’s novel of Professor Fleckner and his all-seeing telephonoscope takes some curious paths in its latter half. Protagonist Blair, aided by his friend Priestley, continue to use Fleckner’s telephonoscope in their attempt to locate the hidden treasure of the criminal syndicate that threatens to take over the world. Making use of his invention’s ability to project images as well as transmit them, Fleckner infiltrates the syndicate and masquerades as its leader so as to learn its secrets. The professor’s motives are less than altruistic, however: the more time he spends as a spy amongst the criminals, the harder he becomes to distinguish from the crooks themselves.

Despite its science fiction gimmick, Treasures of Tantalus draws in large part upon crime thriller standards such as abduction, disguises, drugged coffee, heated chases, doubts over loyalty and subterfuge over inheritance. Then, Smith heads into rather more fanciful territory when the main characters finally turn the telephonoscope on what they believe is the location of the treasure.

The location in question is a vast, gold-filled cave populated by a green-skinned race and their ivory-skinned colonial rulers. Blair and company spend enough time watching this strange new world that they witness an entire melodrama playing out before them as the chief’s daughter Olanda is courted by suitors – a literary precursor of reality TV, perhaps.

Things get even stranger when, as Fleckner adjusts they telephonoscope, the viewers witness the cave people apparently growing older and younger. The professor then hits upon the solution to this puzzle: the cave exists on a planet light years away, and so the images depict events that happened in ancient history; adjusting his device merely alters which point in history they are viewing.

Of course, if the golden caverns exist in another planet, then the location of the crime trust’s earthbound treasure is still a mystery. Fleckner and company all but forget their discovery of a sapient alien species as they return to the earlier question of how to find the loot.

Fortunately, the protagonists continue spying on the criminals long enough to catch word of the treasure’s true resting place, which turns out to be under the sea. Meanwhile, Fleckner grows repentant and eventually decides to abandon his path of corruption. He announces his plan to give his secret telephonoscope to the world, and just so happens to hit upon a formula for ray-proof paint which people can use to preserve their privacy in this brave new world of long-distance communication.

The characters also realise that the aliens they have been watching eventually devastated themselves in a war over iron, a scarce commodity on their gold-filled planet. This fable-like conclusion allows Fleckner to ponder the subjectivity of material value.

Despite the intriguing invention at the centre of his novel, Garrett Smith was apparently unable to turn Treasures of Tantalus into anything other than a meandering trip through familiar stretches of pulp territory.

“The Astounding Discoveries of Doctor Mentiroso” by A. Hyatt Verrill

This story by Amazing regular A. Hyatt Verrill is framed as a letter to the magazine, written in response to other commentators in Amazing’s letters column. In it, the author describes a strange meeting with the noted Peruvian scientist Dr Fenomeno Mentiroso…

This story by Amazing regular A. Hyatt Verrill is framed as a letter to the magazine, written in response to other commentators in Amazing’s letters column. In it, the author describes a strange meeting with the noted Peruvian scientist Dr Fenomeno Mentiroso…

The story begins with the narrator showing an issue of Amazing Stories to Dr. Mentiroso, who immediately flees into a rage over letters that dismiss time travel stories by the likes of H. G. Wells as depicting scientific impossibilities. Mentiroso goes on to argue that a hypothetical aircraft capable of flying at 24,000 miles per hour would be able to travel into the past:

If, when in your 24,000 mile per hour craft, you set your watch in accord with the local time at each point of call it would work out thus when going east: Leaving Lima at noon on Monday you reach Barcelona at 6.30 P. M. Monday, and setting your watch to agree, you proceed to Calcutta where you arrive at 1 A. M. on Tuesday to find your watch indicates 6.45 P. M. Monday. Again altering your watch and heading for Hawaii, you arrive there at 7.30 A. M. Monday, regardless of the fact that your watch says 1.15 A. M. Tuesday and, having readjusted the latter, you proceed and reach Lima at 1 P. M. Monday and find your watch is at 7.45 A. M. Monday. Thus you will have been in the future over six hours at Barcelona, and over eleven hours in Calcutta, but you will have been into the past eighteen hours in Hawaii and back in Lima five and one-half hours before you left this city.

It turns out that Mentiroso has built just such as vehicle. During an archaeological trip, he found a hidden chamber containing texts by a pre-Incan civilisation that knew of the fourth dimension, which Mentiroso refers to as the Esnesnon (“It is invisible, intangible, indescribable, and yet without it the universe could not exist”) and also had a means of harnessing gravity. Using these rediscovered principles, Mentiroso was able to construct a time-travelling craft. He produces this plane and allows the protagonist to take part in an experiment (“Great Scott!” exclaims the narrator upon seeing proof of the experiment’s success). Then, announcing that he will visit the past, Mentiroso disappears – and as the narrator informs us, has yet to return.

Partly Wellsian cosmic exploration, partly a lost civilisation fantasy (exotic settings being a favourite theme of Verrill’s) and partly a more cerebral version of the “comical inventor” stories frequently published in Amazing, “The Astounding Discoveries of Doctor Mentiroso” is presented by Amazing as a puzzle, with readers promised an answer:

Now that you have read the Astounding Discoveries of Dr. Mentiroso, you will want to take a deep breath and come up for air. No doubt, if you are at all human, your head must be in a whirl, and you probably will not know what is fact and what is fiction. At any rate, what is the answer to Dr. Mentiroso’s experiences?

Perhaps you can figure it out yourself, but it will take you quite a while before you hit upon the right solution. At any rate, you may wish to discuss it with your friends for a month. It will make excellent discussion. The answer will be published in the December issue of Amazing Stories.

Discussions

This month’s letters column returns to some of its favourite topics. Frank Allen joins the ever-growing chorus asking for more issues per year, while two more readers send in clippings relevant to the magazine’s stories. John Bull offers a clipping about a Michigan fruit dealer who deposited one dollar in a bank, instructing that the interest be accumulated until the year 2427, when it would be passed on to his descendants; as he notes, this is similar to the plot of “John Jones Dollar”. Sixteen-year-old Lester Sodeman supplies a clipping about the First Baptist church in Florida campaigning against “indecent, immoral and filthy texts and reference books and many rotten fiction books” being held in college libraries; authors under fire include H. G. Wells, Sigmund Freud and George Bernard Shaw.

Fifteen=year-old Donald L. Campbell approves of Holger Lindgren’s suggestion for a science club, but objects to the proposed age limit of eighteen: “You speak of youth being interested in the study of science so why not give them a chance at this club?”

Once again, we have the usual round of comments on the scientific plausibility of Amazing’s stories. Farle B Brown praises the contest winners in the June issue, but not without reservation:

I have one criticism for Mr Wates’ story. Frankly, I consider such a thing as a substance opaque to gravity impossible… The very fact that it is a material substance makes it susceptible and not impervious to gravity.

Still discussing the June issue, he also objects to “Solander’s Radio Tomb” due to the lack of scientific content (“Ellis Parker Butler is a fine humorist and writer, but he has no connection with Amazing Stories“) and expresses doubts about Bob Olson’s “The Four Dimensional Roller-Press” (“will you kindly explain to me how the fourth-dimensional substance which Sidelburg produced inside his quaint arrangement of spheres could possibly have a material existence?”). He does, however, speak approvingly of A. Merritt’s The Moon Pool, which he compares favourably to the stories of Edgar Rice Burroughs (a comparison that leads him to something of a tangent: “The ‘Tarzan’ stories… would be fine lessons for those hypocritical legislators who passed anti-evolution bills in Tennessee and Florida”). An anonymous reader also comments on “The Four Dimensional Roller Press”, objecting to how the story portrays density across dimensions.

Paul Stanchfield, Robert Swisher and Ann Arbor send in a collaborative letter in which they ask “why in Hades do you insist on printing those detectable, boring, out-of-place, and otherwise obnoxious detective stories, called Amazing merely because they include a short paragraph or so explaining the marvellous and complicated mechanism of the spyrogyroheliospermatograph or something of similar nature…?” Also in the line of fire are such “painfully humorous atrocities as ‘Solander’s Radio Tomb,’ ‘Doctor Fosdick,’ ‘Hick’s Inventions with a Kick’ (a big kick), and others of their ilk”. The three readers provide a handy list of suggestions:

First, another cover contest.

Second, if possible, more new stories.

Third, semi-monthly ‘as is’ publication.

Fourth, less detective stories.

Fifth, less detective stories.

Sixth, less detective stories, etc.

A. M. Riordan has a long letter with in-depth constructive criticism. To start with, the letter attempts a genre definition:

The definition of a Scientifiction Story could be thus stated, a story which depicts the intrinsically possible, but not actually existent, as actually existent. It is obvious that a story which depicts the intrinsically impossible, as actually existent, is an effrontery to the intelligence, for the reason that the human intelligence is so constructed that it refuses to function in the presence of known falsehood.

As an example of such impossibilities, Riordan singles out the portrayal of time travel in Cecil B. White’s “The Lost Continent”, an issue also brought up by C. G. Portsmouth in a letter that furnished the editorial to the September issue. Riordan’s letter goes on to complain about “the lack of imaginative nerve of so many of the authors” (“There is entirely too much ruthless slaughtering of innocent heroes and heroines, and entirely too much blowing up and losing of valuable new inventions. The authors get to the end of their imaginations, and take the easiest way out”). Riordan praises Burroughs’ Master Mind of Mars for countering this trend by leaving the door open for further exploits from the protagonist (“The Master Mind of Mars is well on in its sequel in my imagination”).

Riordan also objects to stories “strung out, apparently with the only purpose of making them long”, and points to the sequence in Wells’ War of the Worlds dealing with the narrator’s brother: “The reader of this story did not give two whoops about ‘my brother,'” comments the letter. Another complaint directed at Wells touches upon his portrayal of military tactics: “Mr. Wells certainly commands a punk army… gve an American gun crew one good six inch gun, and the chances that Mr. Wells’ army had and they could clean out the Martians in short order.”

Riordan is not the only letter-writer to take aim at H. G. Wells. S. Francis Koblischke also expresses considerable ire:

I’ve only seen one story by this author which has been able to hold my interest: ‘The Time Machine. The rest of the stuff he has given us has been, I believe, but mediocre reading. There is no snap, no life to his stories. Take, for instance, that last story of his you’ve given us, ‘The War of the Worlds.’ Honestly, this is the rankest, poorest, would-be yarn I’ve ever laid eyes on. What’s it all about anyway? What’s he trying to tell us and WHY? He uses a MULTITIDE of meaningless words and phrases, brewing out of them the sleepiest sort of ‘QUATCH,’ and gets nowhere. How does a writer rated as high as you rate, Mr Wells, get that way anyhow?

S. Kaufman is another Wells critic: “I learned that a shot from a cannon was capable of putting a Martian war machine out of commission, and as later it was found that it was impossible to use cannons why didn’t they send out airplanes? Immediately after learning this fact I lost all interest in the story.” “We suppose,” runs the editor’s response, “that the above letter may be considered a sort of a metaphorical shot from a cannon to knock a very distinguished author from the pedestal on which thousands of admirers have placed him.”

Charles Knight requests that Amazing reprint the planetary stories of Homer Eon Flint; derides the magazine’s comedic stories (“None of them are interesting, and I think most of your readers will agree with me”) and suggests that A. Merritt write a crossover between The Moon Pool and The Face in the Abyss.

R. L. Morris complains that The Land that Time Forgot “is a great strain on the imagination” (“it was an utter impossibility for types of fauna and flora of Palaeozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic, to be living at the same time”) before going on to criticise how authors portray Mars:

Again as regards to the astronomical writers. Why do they always give poor little Mars such a bad time? Simply because the planet is reddish in tint doesn’t necessarily mean it is of a sanguinary disposition, which all fiction in regard to it seems to suggest. The presumption is that being a much older planet than Earth it is by thousands of years more civilized, if life exists at all. Take Edgar Rice Burroughs’ latest brain wave, “Master Mind of Mars,” and all his other yarns about Mars. It is nothing but battle, murder and sudden death, besides having the most grotesque forms of life imaginable. There are men of purple, green, yellow and every color of the spectrum, dressed like Roman warriors, with short swords and, Ye Gods! radium guns. Can you bear it? Again, consider “The Man Who Saved the Earth.” Once more poor little Mars. She tried to drain the Atlantic Ocean. Then we have H. G. Wells’ “The War of the Worlds.” This is an old story, but it is good fiction but at the same time highly improbably. I think Mars is a very much maligned planet.

Abraham Segal describes Ray Cummings’ “Around the Universe” as “delightful” but objects to its sense of humour: “Satire is different–it is laughing at everyone but yourself. But somehow Mr Cummings gives me the atmosphere of ridiculing me at every page.” He also complains about anti-German sentiment in “The Winged Doom”, The Land that Time Forgot and The Moon Pool.

William H. Macpherson hails Lovecraft’s “The Colour Out of Space” as “one of the best I have read in your magazine for a long time” and suggests non-fiction articles on the building of home-made electronic apparatus. Gordon W. Richmond disagrees about the Lovecraft tale: : “There was nothing of scientific value in ‘The Colour Out of Space.’ It was a good story, but it did not fit the standard of your magazine. It had more of a weird, ghostly trend.”

Fifteen-year-old Patten Jackson defends the “slower type of H. G. Wells and Jules Verne” while also expressing appreciation for authors such as Merritt and Burroughs. “A good proof of the merit of Amazing Stories can be found in the friendship which it has made with younger readers”, runs the editorial reply. “No magazine is so hard to edit, as one for the younger generation, and really successful ones may be taken as true classics.” Finally, Harry Hess lists his favourite stories and praises the magazine’s covers.