When faced with a choice of evils, accept the least hazardous and cope with it, unblinkingly.

-David Lamb, as related by Lazarus Long

TL:DR – Lazarus Long plays Scheherazade, gets his groove back and seduces his mother.

TL:DR – Lazarus Long plays Scheherazade, gets his groove back and seduces his mother.

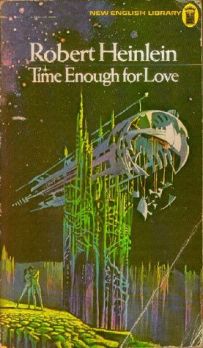

Time Enough for Love is, I think, one of the oddest of Heinlein’s later works. On the face of it, Time Enough for Love is one of the Lazarus Long/Howard Families stories, yet large parts of it consist of Lazarus recounting his adventures (and telling us about the life of a man who might have been a friend of his). It is steeped in a curious mixture of warmth and affection mingled with a cool pragmatism and – to some extent – ruthlessness that one might expect a four-thousand-year old man to possess. It is definitely one of Heinlein’s author tracts.

The framing device is cunningly designed to allow the three stories to be told in a manner that feels almost natural. Returning to Secondus (the planet he founded as the home for the Howard Families (see below)) to die, Lazarus is unwillingly rejuvenated at the command of the Chairman Pro Tem, who feels himself to be in desperate need of Lazarus’s wisdom. The planet he rules is on the verge of a socio-political crisis that may destroy the Howard Families and Lazarus’s legacy. Being a particularly stubborn person, Lazarus counters with an offer; he’ll tell the Chairman Pro Tem stories from his life … if the Chairman can find something new for Lazarus to do. He is, after all, very old.

Lazarus tells three stories, while the Chairman tries to accomplish his side of the bargain. The first – The Tale of the Man Who Was Too Lazy to Fail – is the story of David Lamb, an American naval cadet prior and during WW2, a man so lazy that his approach to everything was to find the way to do it with the least possible expenditure of energy. The second – The Tale of the Twins Who Weren’t – is the story of how Lazarus found himself accidentally responsible for the care of two slaves, a young man and women who could not be set free because they didn’t have the slightest idea how to live as free people. Finally, The Tale of the Adopted Daughter is the story of the single greatest romance in Lazarus’s life, the one girl he never let himself forget.

In the meantime, the Chairman Pro Tem has indeed found something new – a migration to a third homeworld (for the Howard Families) and outright time travel. (Annoyingly, Lazarus only hints at how the second migration (and the establishment of a genuine post-scarcity society) was accomplished.) Armed with his experience, Lazarus sets off on a mission to meet his parents and grandfather … a scheme that goes a little off the rails when he finds himself falling in love with his mother, getting conscripted into World War One and nearly being killed in the trenches. Fortunately, he is rescued in the nick of time by his extended family.

It’s actually quite difficult to review and rate the book because of its format, so I’m going to look at the three stories one by one before assessing the rest of the book.

It’s actually quite difficult to review and rate the book because of its format, so I’m going to look at the three stories one by one before assessing the rest of the book.

The Tale of the Man Who Was Too Lazy to Fail is focused on practicality, on someone who actually did the best he could to reduce the amount of work he actually had to do. Lazarus details the man’s life, from his decision to join the navy to the ways he found to get around both the naval college’s rules and the impediments of society itself. Faced with accidentally having got his girlfriend pregnant, a serious problem in those days and one that could have easily got him booted out of the college, Lamp took the least dangerous option and married the girl in secret, thus – as Heinlein notes – converting the girl’s father from implacable enemy to co-conspirator. Later on, Lamb masters flying and then gets himself assigned to the military bureaucracy, where he streamlines the entire system and, with the advantage of his experience, makes life easier for the men on the front line.

The overall theme of the story, indeed, involves reducing bureaucracy and other elements that slow growth and development, as well as finding ways to take advantage of the laws to make them work in your favour. It is a story of a man who takes a decidedly practical approach to life.

The Tale of the Twins Who Weren’t is a great deal more complex. The twins are decent people, but they have been raised to be slaves. (For someone who has been accused of racism more times than I can count, Heinlein had a lifetime hatred of slavery.) They are simply incapable of surviving in the real world, forcing Lazarus to actually teach them how to be human beings. Matters are more complicated by the twins having been sold as a breeding pair, which means that the twins will be having children … potentially incestuous children.

The overall theme of the story, I think, is about raising children … even if the children are technically grown adults. Lazarus plays father to them, pushing them to stretch their wings – even to the point of subtly encouraging them to defy him – while, at the same time, covertly doing what he can to smooth their path. By the time he’s done, the twins are adults in every sense of the word, although they do have some minor problems from time to time. Lazarus’s unflinching approach to life contrasts neatly with the twins’ naivety. (It also has some amusing moments; when he uses cards to teach the twins about the danger of inbreeding, which is described very well, he gets asked which method he used to cheat.) It’s a very different story from the first, but it does read well.

The overall theme of the story, I think, is about raising children … even if the children are technically grown adults. Lazarus plays father to them, pushing them to stretch their wings – even to the point of subtly encouraging them to defy him – while, at the same time, covertly doing what he can to smooth their path. By the time he’s done, the twins are adults in every sense of the word, although they do have some minor problems from time to time. Lazarus’s unflinching approach to life contrasts neatly with the twins’ naivety. (It also has some amusing moments; when he uses cards to teach the twins about the danger of inbreeding, which is described very well, he gets asked which method he used to cheat.) It’s a very different story from the first, but it does read well.

The Tale of the Adopted Daughter is, perhaps, the weakest of the three. Lazarus, playing the role of a banker on a newly-settled world, accidentally adopts a young girl after rescuing her from a fire and discovering that he was too late to save her parents. As Dora grows older, she eventually falls in love with Lazarus (the only thing saving Lazarus from a charge of wife husbandry is that it’s pretty clear he didn’t mean to do it) and she marries him when he is forced to change his identity. They share a long and happy life together, facing the perils of being settlers on the frontier together, until her eventual death. She was, and remains, the great love of his life. Indeed, as Barb Caffrey points out, the tale helps to humanise Lazarus, who was starting to act a little too old and prickly to be real.

Despite its weakness, and some of the more unfortunate implications, The Tale of the Adopted Daughter works on two levels. On one, it is the story of the obligations a man has to his wife and family, obligations that were already decaying when Heinlein write the book (and are now regarded as somewhat passé.) Lazarus believes, firmly, in putting women and children first, claiming that it is the only principle that can allow civilisation to survive. And on the other, it is the story of how the wrong sort of settlers can really screw up a colony, from idiots who only emigrated because they thought everything would be done for them (one incompetent farmer we meet majored in English Literature) to governors who believe that they can legislate prosperity into existence. As Lazarus notes, somewhat wryly, they haven’t actually found a new way to screw up.

And yet, it skims closer to the limits of the acceptable than either of the other books. The prospect of brother-sister incest is mentioned in The Tale of the Twins Who Weren’t, both in the sense of the twins themselves and their later children (they don’t), but it is brought out more clearly here. Lazarus worries that his son will go sniffing after his daughter, something that obviously worries him. (He has a thinking prejudice against incest). And then there is the morality of someone marrying his ward, although – to be fair – Lazarus is older than practically everyone at this point. Your mileage may vary.

The final section of the book provides a perfect opportunity for contrasting the far future with 1916 America. On one hand, we have a world where technology has reached the point where humans are no longer bound by society’s chains. Everything from taboos against incest and homosexuality to war, racism and death are nothing more than distant memories. And, on the other hand, we have a very well-drawn picture of a state where society’s chains bind everyone, even the most powerful. The future people simply do not comprehend the world that birthed Lazarus, to the point where one woman confidently states that a sex worker is rich enough to support her brother … a statement that is flatly incorrect, as ‘sex worker’ was hardly a well-paying job in 1916! Heinlein wonderfully demonstrates the hypocrisy that the locals have to embrace, constantly, just to survive.

The final section of the book provides a perfect opportunity for contrasting the far future with 1916 America. On one hand, we have a world where technology has reached the point where humans are no longer bound by society’s chains. Everything from taboos against incest and homosexuality to war, racism and death are nothing more than distant memories. And, on the other hand, we have a very well-drawn picture of a state where society’s chains bind everyone, even the most powerful. The future people simply do not comprehend the world that birthed Lazarus, to the point where one woman confidently states that a sex worker is rich enough to support her brother … a statement that is flatly incorrect, as ‘sex worker’ was hardly a well-paying job in 1916! Heinlein wonderfully demonstrates the hypocrisy that the locals have to embrace, constantly, just to survive.

In many ways, this is a theme that runs through all of Heinlein’s later books. Mankind is bound by society’s chains because those chains have to exist, under the circumstances; when circumstances change, the chains change too. A woman in 1916 who had sex before (or outside) marriage ran the risk of getting pregnant and thus facing utter ruin; later, went cheap and effective forms of birth control were developed, women were freed from the chains that society had needed to place on them. Heinlein was all too aware of the existence of these chains, but he was also willing to speculate about worlds where those chains did not exist – and what would be necessary to remove them. As such, he remains one of the most realistic and yet idealistic writers of his world.

But the section also includes one of the more icky parts of the book – Lazarus’s love affair with his mother. One may argue that, once sex has been separated from reproduction (and tools have been developed to ensure that a particular couple are a good match), that incest will no longer be as taboo as it is today. I find that hard to believe, even though there is a truly vast gulf between Lazarus and his past self. The whole affair leaves a bad taste in my mouth. Heinlein may have wanted to shock – I think he did like shocking people in his later works – but I found it hard to stomach.

Lazarus also spends a lot of time chatting about his past experiences and offering words of wisdom from his life, often referring to past adventures and drawing some of Heinlein’s older works into his future history. Some of his stories are rather contradictory, which has some amusing effects; his listeners tell him, at one point, that they’ve already heard several different versions of a particular lie. Others are remarkably practical: Lazarus notes that a machine politician is trustworthy because he knows he needs the voters to stay on his side, but a reform politician will break his word whenever he can justify it to himself. This may be remarkably optimistic of him. Our current generation of machine politicians have proven themselves quite incompetent. Many of his sayings, collected under the heading of The Notebooks of Lazarus Long, are quite quotable.

The book also, perhaps unsurprisingly, focuses on love. Lazarus is the central character, in many ways, but the side characters have their own romances. Minerva – a computer turned human – has a relationship with Ira, Galahad has a relationship with two girls … the story touches on many other relationships, for differing values of good and bad. Indeed, it considers the other forms of love – the love one might have for a parent or for a sibling or even for a friend – almost as much as it touches on romantic love. It also notes how love can change a person, for the better or the worse. One of his ex-wives got greedy, he says, which he blames on her new husband.

The book also, perhaps unsurprisingly, focuses on love. Lazarus is the central character, in many ways, but the side characters have their own romances. Minerva – a computer turned human – has a relationship with Ira, Galahad has a relationship with two girls … the story touches on many other relationships, for differing values of good and bad. Indeed, it considers the other forms of love – the love one might have for a parent or for a sibling or even for a friend – almost as much as it touches on romantic love. It also notes how love can change a person, for the better or the worse. One of his ex-wives got greedy, he says, which he blames on her new husband.

Overall, I am left with mixed feelings about Time Enough for Love. It is a collection of stories and snippets, which can be mined for advice – and much of it is good advice – but very little of it is politically correct. There will be people who will recoil in horror … not because of the incest, but because Heinlein did not mouth platitudes. Indeed, for all the super-technology at the far end of Heinlein’s history, Heinlein is careful not to give us easy answers. We simply do not have that kind of technology yet.

In the end, the book is an interesting read. But, unlike many other books by Heinlein, Time Enough for Love requires a great deal of commitment from its reader …

… And many will feel that it has simply not aged very

A book that interests me book I cannot get myself to make the plunge. I was not able to get through “Number Of The Beast” and I fear that this might aldo fall into that category on my bookshelf…

Incomplete last sentence? “… And many will feel that it simply has not aged very well.”