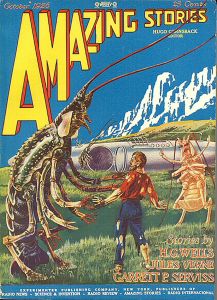

A man with a heavy beard and tattered clothes stands on a grassy plain, looking like a latter-day Robinson Crusoe. Towering above him is a lobster-like creature, which stands on its hind legs while stroking him with its front appendages, almost as though greeting him. Two more beings of the same species can be seen in the background; one stands by the entrance to a futuristic vessel. It is October 1926, and Amazing Stories is ready to take its readers on a journey to the farthest corners of the globe.

A man with a heavy beard and tattered clothes stands on a grassy plain, looking like a latter-day Robinson Crusoe. Towering above him is a lobster-like creature, which stands on its hind legs while stroking him with its front appendages, almost as though greeting him. Two more beings of the same species can be seen in the background; one stands by the entrance to a futuristic vessel. It is October 1926, and Amazing Stories is ready to take its readers on a journey to the farthest corners of the globe.

This month, Hugo Gernsback’s editorial discusses the influence of science fiction on real-life invention. “[Many] devices predicted by scientifiction authors have literally come true for many generations”, he says, and argues that even the most implausible SF may at least offer inspiration for scientific progress. Decades after Gernsback made this observation, Ray Bradbury would speak in agreement: “I’ve talked to more biochemists and more astronomers and technologists in various fields, who, when they were 10 years old, fell in love with John Carter and Tarzan and decided to become something romantic. [Edgar Rice] Burroughs put us on the moon.”

This issue of Amazing has a distinct theme, as most of the stories involve travel to various exotic locales. Let us take a closer look at them…

“Beyond the Pole” by A. Hyatt Verrill (part 1)

The longest work of original fiction yet printed in Amazing Stories, “Beyond the Pole” begins with a sailor named Frank Bishop ending up as a lone castaway in the Antarctic. After traversing a mountain range, he comes across an area with a strangely warm climate and wildlife unknown to zoology. First, he finds a species of penguin-like bird; he then sees a forty-foot lizard from afar; next, he kills a mammal which he initially takes for a deer, but which turns out to actually be a giant rat-like being (oddly, he fails to notice this until after he has partially consumed the fallen beast). His most significant discovery of all, however, is a race of bipedal crustaceans.

The longest work of original fiction yet printed in Amazing Stories, “Beyond the Pole” begins with a sailor named Frank Bishop ending up as a lone castaway in the Antarctic. After traversing a mountain range, he comes across an area with a strangely warm climate and wildlife unknown to zoology. First, he finds a species of penguin-like bird; he then sees a forty-foot lizard from afar; next, he kills a mammal which he initially takes for a deer, but which turns out to actually be a giant rat-like being (oddly, he fails to notice this until after he has partially consumed the fallen beast). His most significant discovery of all, however, is a race of bipedal crustaceans.

These are sapient creatures possessing the power of telepathy, which they use to inform Frank about their society. Their technology is built upon two elements in particular: an immensely malleable metal more versatile than anything known to mankind, and atomic energy. Their inventions include advanced aircraft, but as they are physically incapable of surviving at high altitudes, they cannot travel beyond the mountain range that encircles their land.

So far, “Beyond the Pole” noticeably lacking in plot, having a meagre storyline designed purely to convey its SF ideas. In this way it is comparable to Hugo Gernsback’s own novel Ralph 124C 41+ – but while Gernsback was interested in technological innovation, Verrill’s story prefers to play with natural sciences.

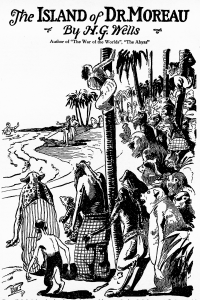

The Island of Doctor Moreau by H. G. Wells (part 1)

After an accident at sea, Edward Prendick is stranded on an island with some very strange inhabitants. The local patriarch is one Dr. Moreau, a vivisectionist driven from the scientific community due to accusations of animal cruelty. Accompanying Moreau are what appear to be the island’s natives; the closer Pendrick gets to these people, the more deformed and bestial they seem.

After an accident at sea, Edward Prendick is stranded on an island with some very strange inhabitants. The local patriarch is one Dr. Moreau, a vivisectionist driven from the scientific community due to accusations of animal cruelty. Accompanying Moreau are what appear to be the island’s natives; the closer Pendrick gets to these people, the more deformed and bestial they seem.

Eventually, Prendick walks in on Moreau conducting a surgical on one of the men, and becomes convinced that Moreau is responsible for turning the people of the island into half-animal freaks using vivisection. Despite his terror of them, the Beast-Men accept Prendick as one of their own, subjecting him to a bizarre initiation ceremony.

Finally, Prendick confronts Moreau. Amazing‘s first instalment of the novel ends just as the Doctor is about to reveal the true nature of his experiments…

Amazing had previously reprinted short stories by H. G. Wells, but The Island of Doctor Moreau (originally published in 1896) is the first of Wells’ novels to be serialised in the magazine. It is a good book to start on: Wells starts out by hooking the reader’s interest as an adventure story, before gradually building a sense that something deeply wrong is occurring. Even the first part of this serialised version leaves a heavy impact.

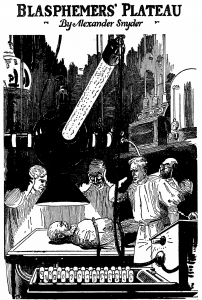

“Blasphemers’ Plateau” by Alexander Snyder

Archaeologist Gary Mason has set off to visit an old friend of his, a reclusive biologist named Dr. Oliver Santurn. The doctor has a colourful reputation amongst the locals: they say that he has a menagerie and aquarium, and yet nobody has seen a single animal transported to his home. People know that he is conducting experiments, but exactly what kind of experiments is a mystery.

Archaeologist Gary Mason has set off to visit an old friend of his, a reclusive biologist named Dr. Oliver Santurn. The doctor has a colourful reputation amongst the locals: they say that he has a menagerie and aquarium, and yet nobody has seen a single animal transported to his home. People know that he is conducting experiments, but exactly what kind of experiments is a mystery.

Upon reaching Santurn’s heavily-guarded home, Mason finds that his friend has developed a new set of interests since last they met. After Mason remarks on a shelf of theological volumes, Dr. Santurn explains that his current work is an effort to “throw new light on Immortality and the Resurrection via the laboratory route.”

The Doctor shows Mason around his menagerie, and reveals that he has been creating animals synthetically by manipulating molecules with “Neo Waves”. He compares himself to God, and Mason is disgusted by this blasphemy. “’Me und Gott’ as the Kaiser once remarked”, he says to his biologist friend. “You’re a megalomaniac.”

Santurn goes on to explain that his ultimate aim is to disprove the existence of the soul, and thereby to abolish all religion, which he regards as “the curse of humanity”: “When there are no barriers of religion between man and man, such as differences in faith now present, then the Brotherhood of Man will have arrived.”

Inevitably, Santurn’s next experiment is to create a human being. He goes ahead with developing a foetus, which emerges from its incubator as a crying baby – to Mason’s horror. In an inventive literary reference, Santurn names the child after Shakespeare’s Macduff, a man who was not born of a woman. The baby is born with a mental handicap, so Santurn arranges for an additional procedure that will give the baby the mind of a genius – but this operation is disrupted by Mason. As punishment, Santurn subject Mason to an opposite treatment, leaving him with the mind of a three-year-old child.

Then, Santurn realises that he has developed cancer from exposure to the Neo Waves. His final act is to set off a self-destruct mechanism, blowing the laboratory to bits.

An original acquisition by Amazing, “Blasphemer’s Plateau” is an obvious spin on the Frankenstein theme. Mary Shelley’s novel is specifically alluded to, albeit in an odd context: Mason contemplates using Santurn’s animals “as Frankensteins” to destroy the laboratory. Beginning with a lone traveller heading to a gothic structure spoken of in hushed tones by locals, and ending with a laboratory exploding, the story is knee-deep in what would become clichés of mad scientist films in later years. Oddly enough, one of the scientists in Frank R. Paul’s illustration looks rather like Ernest Thesiger, who went on to co-star in Bride of Frankenstein nearly a decade later.

As an example of its subgenre, “Blasphemers’ Plateau” is rather muddled. It is unclear as to whether Mason is meant to be seen as an entirely sympathetic protagonist: his increasingly destructive and unhinged response to the “blasphemies” surrounding him, with Biblical references to Sodom and Gomorrah running through his head, make him seem scarcely less fanatical than Santurn. Meanwhile, Santurn’s ultimate downfall comes across as arbitrary, being too loosely connected to the nature of his experiments to convince as poetic justice.

Alexander Snyder contributed one further story to Amazing – “The Coral Experiment”, in the September 1929 issue – but his contributions to science fiction appear to end there.

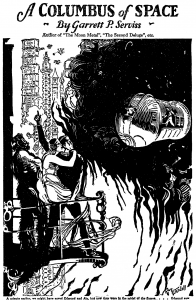

A Columbus of Space by Garrett P. Serviss (part 3)

Spacefarer Edmund and company conclude their atomic-powered trip to Venus, and the ending to the story is as uneven as its beginning and middle – even if the magazine’s introduction hails it as offering “an accurate scientific analysis of what might be found on Venus should the planet ever be expored [sic].” The story has the occasional high point, as when it introduces the intriguing, synesthesia-like notion of interplay between sounds and colours upon Venus: “The saying of the flowers in the breeze and the rhythmic motion of the bird’s plumage produce harmonious combinations and recombination of colours which are transformed into sounds as exquisite as those of the world of insects”, explains Edmund.

Spacefarer Edmund and company conclude their atomic-powered trip to Venus, and the ending to the story is as uneven as its beginning and middle – even if the magazine’s introduction hails it as offering “an accurate scientific analysis of what might be found on Venus should the planet ever be expored [sic].” The story has the occasional high point, as when it introduces the intriguing, synesthesia-like notion of interplay between sounds and colours upon Venus: “The saying of the flowers in the breeze and the rhythmic motion of the bird’s plumage produce harmonious combinations and recombination of colours which are transformed into sounds as exquisite as those of the world of insects”, explains Edmund.

But the trouble is that Serviss struggles to build these ideas into a worthwhile story. The novel’s failings as a narrative are perhaps best summed up by the death of the crew’s Venusian companion, Jubal; the author is meant to find this an emotionally heavy moment, despite Jubal being scarcely more developed as a character than the anonymous Venusians who perished earlier in the novel, and whose demises were quickly forgotten by everyone concerned.

There is more death and destruction in store when the Sun makes itself visible – a rarity on cloud-shrouded Venus. An unfortunate mishap involving an oversized lens causes the Venusian capital to catch fire, and countless citizens – including the beautiful Queen Ala – perish while the humans escape.

Originally published in 1909, A Columbus of Space in some ways prefigures the planetary romances later written by Edgar Rice Burroughs. But it does not sure Burroughs’ instinctive grasp of romance and adventure: what should have been a tale of heroic discovery ends up as a checklist of catastrophes caused by Earthman and Venusian alike.

The Purchase of the North Pole by Jules Verne (part 2)

As Impey Barbicane and his Baltimore Gun Club plan to alter Earth’s axis using an enormous cannon, thereby thawing the Arctic and rendering the northern regions accessible, a Frenchman named Alcide Pierdeux decides to take a closer look at the potential side-effects of this endeavour. He concludes that the experiment would lead to a series of disasters across the globe, and his findings prompt concerned parties to try and track down the Gun Club’s operations.

As Impey Barbicane and his Baltimore Gun Club plan to alter Earth’s axis using an enormous cannon, thereby thawing the Arctic and rendering the northern regions accessible, a Frenchman named Alcide Pierdeux decides to take a closer look at the potential side-effects of this endeavour. He concludes that the experiment would lead to a series of disasters across the globe, and his findings prompt concerned parties to try and track down the Gun Club’s operations.

It turns out that Barbicane and his crew are building the cannon into Kilimanjaro, aided by a despotic sultan. Pierdeux is powerless to prevent the project from going ahead; the cannon is duly constructed, and eventually fired. This causes great destruction amongst nearby towns and villages – but Earth’s axis remains unchanged.

As it happens, Gun Club’s resident mathematician J. T. Maston made an error in his calculations: he was working on the basis that the Earth is forty thousand, rather than forty million, metres in circumference. For the plan to work, the Gun Club would have needed not one giant cannon, but a quintillion. The world hails Maston as a hero, as this mistake inadvertently saved the world. Maston himself, meanwhile, marries Mrs. Scorbitt, with whom he had argued at the start of the novel – and who was responsible for his error in the first place, as she gave him a telephone call while he was working at his blackboard.

The Purchase of the North Pole departs from the adventure-driven plots that characterise Verne’s best-known novels and instead tries something different, being a sort of scientific farce. Amazing had published comedic “wacky inventor” stories before, but nothing on quite such a grand scale as Barbicane and Maston’s disastrous scheme.

And finally…

The issue contains more poetry by Leland S. Copeland. The first is entitled “Hail and Good-By”:

Where counter star-streams meet and blend,

Where suns and comets fly,

We wake at last in human form

To ponder whence and why.

A billion billion ages lapsed,

A trillion worlds went by,

Ere we could rise from light and dust

To labor, love, and die.

Far out within the Milky Way

Our pellet Earth is cast,

Whose children dream that mind will live

When all the stars have passed.

We cannot glimpse the future’s gift,

But one thought holds us fast—

To think, to try, is good, and then

To vanish in the Vast.

The second, “Lullaby”, comes at the end of the magazine:

Hush, little nebula,

Don’t you cry;

You’ll be a blue star

By and by.

Color will alter—

Gold, red, and black,

One after another,

Will garnish your back.

Kiddies called planets

Will spring from your side.

Curling and whirling,

World-stuff will ride.

Round a vast circle,

Performing a year;

Heat must go etherward,

Cool lands appear.

Life soon will follow—

Amoeba and worm;

Dinosaur, mammoth,

And Brain for a term.

Warring and slaying,

Fighting for mates,

Brain must live stories

Of loves and of hates.

Wisdom will triumph,

War lords must die,

Happiness triple,

For Brain can go high.

Planet on planet,

Will crash—but don’t sigh;

Again you’ll be nebula

By and by.